I know you. I know you in a way you can’t even imagine.

I know you by the times you keep, the places you go. You don’t know I’m here. I’m invisible to you. Here, curled in the corner of this shop doorway, with my knees drawn up. I lower my head as you approach, click-clacking on those heels, off to work, and you walk by without even a glance. No idea you’re being studied, watched, followed.

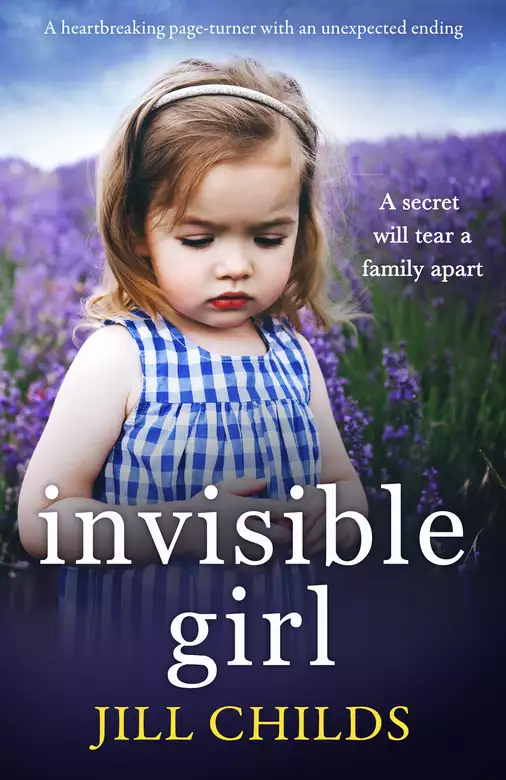

This morning, you’re running late and your little girl, tugged by the hand, scurries to keep up with you as you stride down the road towards school. She’s well turned out: hair scraped back, uniform clean and pressed. She’s a little scrawny. Maybe that’s because you struggle with the bills; maybe she’s just made that way. You turn right at the corner and disappear from sight. Gone now, for the day.

I shuffle to my feet, gather together my bags and slowly move off again, back into motion, down towards the park. There’s a chance of breakfast there, at the corner café, round the back. Mick might come. They let him charge his phone. They’re kind folk. I see it in their eyes. They understand. They seem to know what it’s like to go hungry.

That man visited you again last night, didn’t he? I saw you come to the door of the block of flats to greet him, saw his arms reach for you as he stepped inside, out of the darkness, out of the cold. You didn’t feel that I was watching, crouched in the doorway of the electrical shop across the road, hiding in the shadows.

Why do you let him come to you, time after time? Do you love him? He doesn’t pay you, I hope. Please, no. I couldn’t bear that. That smart man in the cashmere coat. Late, as always, long after your daughter was asleep in bed. I want to understand. I want to know you.

I kept watch until the coffee shops closed. Even the Thai restaurant on the corner went dark. I waited for him to leave again. Why does he sneak to and from your door in the darkness, like an alley cat? Why have I never seen you together in daylight? Is he already married? You deserve better.

I want to ask you, one day. You don’t know how much I long to ask. I want to be a real person to you, visible at last. I long for it but I fear it, too, fear it most of all. What would you say? Could you ever forgive me? I never forgot, you see. I never stopped searching for you. It was only the hope of finding you that kept me tethered to this world.

So, I hesitate. I bide my time, for now. That’s one thing I’m good at now. Waiting. And watching.

I don’t know when I first saw her – I mean, really noticed her. It was only because of Rosie.

I know it sounds callous but there are so many homeless people on the high street now. They sort of mushroom in dark places. Hunched shapes in corners and doorways, sitting slumped against shop fronts, their legs invisible in grubby sleeping bags and tatty plastic carriers of belongings clustered around them.

It isn’t that I’m not aware of them. I am. Painfully aware. I feel guilty every time I walk past someone and pretend not to see them. It’s inhumane. I’m embarrassed that I have enough to eat and a roof over my head, and they don’t. But how much can I really do to help? A pound here, fifty pence there. It feels so inadequate and I end up doing nothing at all.

I used to argue with Mark about it. He was always cross if I stopped to give coins to a beggar. He called me naïve, as if kindness was something I needed to grow out of.

‘They’ll only spend it on drink or drugs,’ he scoffed. ‘You’re not doing them a favour, not really.’

For a while, I bought a cup of coffee every day for the man outside the supermarket but he went a bit strange, started complaining that it didn’t have enough milk and sugar and started shouting at me, and I avoided him after that. Mental health problems, clearly. Even so, no one should sleep rough nowadays, not in our society. Even if there are deeper problems.

There are other ways of helping and I do give what I can to charities. The local church runs a shelter over the winter – well, it’s the church hall and homeless people can go in and sleep there on Monday nights and volunteers cook them supper and breakfast the next morning. I know because when Rosie was smaller, before she started school, we used to go to playgroup on Tuesday mornings and, oh dear, the smell when you walked in at half past nine. Poor souls. We had to open all the windows, however cold it was, and then watch like hawks to make sure none of the toddlers tried to climb up onto the cupboards and fall out.

But Maddy? Well, she was probably there in one of the doorways for a while before I really noticed her.

It’s Rosie who sees her first. I mean, actually sees her.

We’re just about to cross the main road, coming back from school. I’ve got a bag of shopping and Rosie’s book bag in one hand, and I’m trying to hang onto her with the other. She and her big brother, Alex, move at different speeds when they’re out with me. He’s the impatient teenager, eye-rolling, embarrassed, hurrying me home. She tends to drag, like a dog on a lead. She’s in a world of her own: typical five-year-old. Anyway, the lights change and the crossing starts beeping and I make to step forward into the road and she’s like a dead weight, dragging me back. And you never get long at that junction.

‘Rosie. Come on.’

She twists around, staring back at the bundle of person on the pavement there, near the crossing. A good place to beg. Somewhere people have to stop. I glance at her. She’s sitting on the far side of the pavement, back against the brickwork, with her legs drawn up and a dirty duvet or blanket tucked around her knees. She’s wearing a stained, blue padded jacket with a rip at the top of the sleeve which bleeds white stuffing. Her hair’s matted and her face is ingrained with dirt, all along the creases of her mouth and nose, black as if someone had drawn her in charcoal. Her eyes are startling. Very blue, like the jacket. Intense. And she’s looking right at us. Still and appraising, as if she’s reading us. A bit spooky.

I look down at Rosie. She’s looking right back at the woman, with a funny expression on her face. Not repulsed, which is what I’d expect, to be honest, just thoughtful.

She tugs at my hand. She doesn’t take her eyes off the woman.

‘That lady hasn’t got a home.’

I stoop down to her to keep my voice low. Embarrassing. The woman probably heard.

‘I know, sweetheart. But we need to go.’ I tug on Rosie’s hand to get her attention and move her forward into the road.

She digs her heels in. ‘But why?’

The crossing switches from the green man to the hurry-up countdown. Ten. Nine. Eight. Missed it. I sigh. I’ve bought frozen peas; they’re probably melting. The cars rev up again and start to stream past us.

‘How about spaghetti carbonara for dinner?’ Alex is going to a friend’s house after school so it’s just the two of us.

Still, Rosie and the woman stare at each other, eyes locked as if they’re reading each other’s souls.

I keep a tight hold of her hand. ‘And garlic bread?’

Rosie tips her face up to me and says in a low voice, as if she’s settled something: ‘She could live with us.’

‘No, my love. She couldn’t.’ I try to keep my tone casual, willing the lights to change again.

Rosie frowns. ‘Why not?’

‘We haven’t got room.’ It’s the first reason that comes into my head and it’s true – we’re cramped as it is.

Rosie frowns as she considers. ‘She could have the sofa bed. In the sitting room.’

Mercifully, the lights turn amber and I get ready to move. ‘Let’s go.’

I practically drag her across the road. Her head is still turned back, her eyes on that woman. She’s a funny kid, Rosie. She’s confident and a bit overbearing sometimes, but she’s thoughtful, too.

When we reach the other side, she finally faces front again. I take a quick look back over my shoulder at the corner. The homeless woman is looking after us and she has a smile on her lips and a faraway look in her eyes. I wonder how much she’d heard. Probably nothing. Probably she’s just on drugs.

I think, Well, that’s that.

I have no idea.

Time’s the thing. It warps. It slows, slows, then it stops. Traffic lights changing; people walking; hurry scurry; shop shutters up, shop shutters down – it’s all one.

Out of joint.

And if it is moving, how can I tell? No watch. No clock. Stop the clocks. Is that Shakespeare? Maybe, maybe not. Church bells on Sunday. That’s an anchor – marks out the morning. Calling the faithful. Ding, dong, the witch is dead. The sun, of course. That’s the first of it: clotted grey light seeping into the blackness, waking me up. Splitting my head open when I want it to go away, leave me alone. No need, waking me up. For what?

It’s all gone, always, by morning – whatever liquid lubrication came to hand the night before. Mouth parched, head screeching, feet frozen. Nothing left to take the edge off. Empty arms, empty bottles – story of my life. I take a moment, coming to, working out where I am. For a moment, floundering to the surface through the mud, the darkness, I’m a child, in that boxy army-issue bed in Cyprus, Mum and Dad in the next room. The ceiling fan going whop, whop overhead, stirring the heat. The distant murmur of waves cracking the shore and rattling the stones like fistfuls of dice as they scrape back.

Then I’m a young woman again, sleeping beside John, sex-drunk, wine-drunk, long-limbed and lazy. Then the cramps hit me and life drags me back here. Muscle aches. Bones aches. Feet, legs, back, shoulders. Old woman aches, too soon. Before their time. And I shift my weight and taste the sourness in my mouth, feel the crustiness in my eyes and here I am, still alive, still kicking, against all odds, and so it begins.

I’ve found a new spot at the back of the small park, down by the river. Children’s playground at one end and a tennis court, but trees and thick bushes at the other. You have to time it just right. They lock the gate at dusk. But it’s not impossible. Those are good nights.

I go for the rhododendron bushes. Hollow in the middle and pretty dry. You crawl in low and pop up, inside the canopy. We used them as dens when we were kids – not here, back in Yorkshire. Hide and seek. And for spelling tests, later. Rhododendron. Onomatopoeia. Words like those sort the wheat from the chaff. The sheep from the goats.

The smells take me back. Damp earth. Splitting sap. Blossom. Yorkshire, at the campsite. Always bloody raining. And earlier, playing with that neighbour girl in Cyprus, bright, bright sunlight and the smell of fresh sweat and pine needles. What was her name? Daphne? Where’s Daphne now?

I peer out now, through bleary eyes, at the thick mist rising from the river, cupping the trees. The grit and grey of winter – I try to think of spring. Will I even see it? Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow. Downright morbid, the Scottish play. Self-obsessed. And look at me now, more weird sister than Lady Macbeth. Old hag. Fifty-four. Knock at the door. Death’s door, if I’m not careful.

The light finds me, even here, long fingers poking in between the leaves, a greenish tinge. That’s the worst part of the day, out here: the start. The cold freezes your bones. Bone chill. No roof. No toilet. No sink. No kettle. No other person, even. Another warm, breathing human being to say good morning and look me in the face as if they can actually see me, a mirror to tell me I’m still alive. Creaking joints. Backache. Hot steam rising as I pee in the bushes and crawl out. Hello, new bloody day, like it or not. Still here then, Maddy, old girl. Off we go.

A young man bought me a cup of tea and a cheese and pickle sandwich yesterday. The kindness of strangers never ceases to amaze. Chicken would be more my thing but mustn’t grumble.

And that little girl on the corner. She saw me. I am still here. The memory of her comes bursting through the headache and the pains. That was the lightness in my head when I fell into sleep, that was it. That little girl. I stand and stretch slowly and feel the weak sun on my face, watery through the cloud but there, still there. Maybe she’s the way, my God-given chance. Because I’ve seen them together – the girl from the corner and the other little girl – skipping down the high street on either side of that woman. Saturdays. And coming home together after school once, too, holding hands. Friends.

I gather together the jumble of bulging plastic bags with their torn handles and heavy damp and start to walk towards the back of the park, towards the café, opening soon. One foot in front of the other, that’s the way.

There’s another line, there in my head. Something the ocean and sweep up the wood. But that’s not Shakespeare, that one. Think, Maddy. Come on, you know this one. A modern poet, I used to teach him, too, born up in the north somewhere. Auden! Yes! Old W.H. Auden, wasn’t it?

Stop all the clocks… Sweep up the wood. For nothing now can ever come to any good.

It’s all because of the money. I get paid on the fifteenth of each month and it’s always a stretch, at the best of times, making it through. I love working at the wine bar but it’s only part-time work and cooking never pays well, even with a share of the tips; but I can’t complain, I’m lucky with the hours. The lunch shift fits perfectly with school and Jane is very good. If customers sit late over coffee, she always lets me out on time.

But December’s been tough. I really shop around and do my best to find bargains but Alex is set on some computer game that costs a small fortune and he’s canny enough now, at fourteen, to know the difference between the real thing and a market stall knock-off. And Rosie deserves some decent Christmas presents, too.

And then there’s food and everything. If I’ve got to host Christmas lunch and include Mark and his mother, I want to put on a good show and do it properly. I’m still angry about it. Mark bullied me and I wish I’d never caved in.

I told him I’d send the children over in the morning so he could do gifts with them. But he didn’t want that – he wanted us all together, as if nothing had ever happened between us. He argued that he only wanted what’s best for the children. It wasn’t about him, it was all about them. As if I didn’t spend my whole life trying to put Alex and Rosie first.

Then it became pleading. ‘Just one day of the year, Becca.’ His face was pathetic with need. ‘Please, let me have that, I’m begging you.’

Finally, when I tried to stand firm and said I needed time to think about it, he turned nasty and started saying I was selfish and spiteful and who knows what else. He wrote one of his childish letters about it, full of crude insults and threats.

I’ve kept all his venomous letters, all locked away in an old suitcase so Alex can’t come across them by accident. I feel I need evidence, in case anyone turns around in the future and says I was wrong to leave him, that he’s a lovely man. Well, he can be, on the surface. No one else saw how subtly controlling he became over the years, how manipulative. Maybe I need evidence for myself, too, on the days I can’t quite believe I really left him and how vindictive he became once I did.

Anyway, he wore me down, in the end, about Christmas Day, and I agreed to let him and his mother come for one last Christmas lunch together as a family. And then never again.

So I’d already drained the bank account when the gas bill came in – a big one; how can you switch the heating off when it’s so damn cold? – so I was hanging on by my fingernails until the fifteenth and praying the kids didn’t suddenly demand money for this or that. There’s always something at school – presents for teachers, collections, sponsoring them for one thing or another.

On the fifteenth, I don’t make it to the cash machine before school pick-up: it’s too busy at the wine bar. But on the way home, I tell Alex and Rosie to just wait a minute while I check the account and draw out a lump of cash to last me through the rest of the shopping. It’s a habit of mine. I’ve got cards but I’m more conscious of the cost of things if I have the money in my bag and count out notes. It puts me off spending too much.

It’s icy – a real cold snap – and just starting to rain. My fingers go numb in the few minutes it takes me to work the cash machine. I’m nearly done when Alex pulls at my arm.

‘Mum. Stop her. Please.’

He looks crippled with embarrassment. They’re such different kids, those two. Chalk and cheese. And he’s at an awkward age anyway, fourteen.

Rosie, of course. I told her to stand where she was, just for two minutes, but she’s wandered off, and she’s leaning over that homeless woman who’s tucked out of the rain in the doorway of a residential block a few doors further down.

‘Rosie!’

She doesn’t turn. She’s bending forward, her arms resting on the top of her legs, peering down at the woman as if she’s examining an interesting insect. It makes my skin crawl, just watching. I don’t mean to be rude but she must smell awful, that woman, and I don’t want Rosie anywhere near her.

‘Rosie!’ No response. Whatever they’re talking about – and they are talking, I can tell – Rosie is absorbed. I glance down at Alex. He’s grimacing, his face showing the disgust I feel but am trying not to show.

‘Just get her, would you, Alex?’

He hunches his shoulders and strides off towards her. I turn back to the machine and pull out the printed statement. My money’s gone in. Thank God. I key in a request for £250 and unzip the middle pocket in my bag, ready to hide it away at once.

‘Let GO!’

A high-pitched scream. I twist around, cursing under my breath. Alex is gripping Rosie’s shoulder and trying to drag her away while she struggles and flails. Her hand catches him and a slap splatters across Alex’s cheek. The woman, a shapeless mass of old clothes, rises to her feet in the shadows and reaches for them, trying to intervene. Her hands are curled, like claws. Grasping for my children.

‘Stop!’ I run down to them, shoes slapping on the pavement, and pull the two of them apart, turn them smartly, my hands gripping their arms, to march them away.

‘Sorry.’ I call over my shoulder to the woman without looking her in the face. Too close – she was too close to them. I want distance. The rain flies in our faces, heavier now. We just need to get home, to get warm.

After a few steps, I turn to my son. ‘For heaven’s sake. What’s the matter with you?’

Alex says at once: ‘It wasn’t me. It was—’

I propel them forward. ‘That’s enough. I don’t want to hear it.’

Alex goes into a sulk and drags himself along by my side, eyes on the ground. I can sense the glower without seeing it.

Rosie twists her head to look at me. She doesn’t look cowed, she looks pert and confident as if she’s certain she’s in the right and I’m just over-reacting.

‘What, Mummy? I was just talking to that lady.’

‘Two minutes.’ The rain thickens, strikes my nose and dribbles down my chin. ‘Really? You can’t do what you’re told for two minutes?’

She shrugs, her face composed. For a few minutes, we struggle forward in a line, fighting the wind. I relax my grip on them as we near the corner and turn into our road.

‘I know something you don’t know.’ Rosie tries to look around me to Alex to see if he’s rising to the bait. He shoots her an evil glance. ‘Maddy. She’s called Maddy.’ Rosie smiles up at me, triumphant. I can almost hear her, stooping low over the heap of homeless woman, saying in her chirpy, beguiling voice: ‘Hello. I’m Rosie. What’s your name?’

‘You know what else?’

We’re at the front door of the block now and I’m scrabbling to reach through my coat to fish the keys out of my zipped pocket. My hands are so numb, it’s a struggle to get the keys in the lock, then to turn them. Alex pushes his way past me as soon as the door opens and stomps up the stairs towards our flat on the top floor.

I close the door and feel the relief of being inside in the stillness, safe, out of the wind and rain. I coax Rosie up the stairs and we pile inside. Alex disappears to their room. I take Rosie’s coat from her, then draw her after me into the kitchen to give her wet hair a rub.

She’s still talking. ‘She’s got the same name as a cake. She said.’

I’m only half listening. ‘A cake?’

She nods emphatically and chuckles to herself. ‘She’s funny.’

I set her up at the kitchen table with some colouring and put the kettle on, then started to unpack the shopping and start on tea. My feet ache and my head is throbbing and I’m shivery. The rain has seeped through my coat and spilled wet patches across my shoulders and upper arms. I ought to go and change but it’s already half past four and I want dinner on the table for five or we’ll never get through homework and baths and everything else by bedtime.

It isn’t until eight, when Rosie is already asleep in bed and Alex has finished his school work and lies sprawled on the floor, lost in a computer game, his thumbs flashing at a ridiculous speed, that I go to find my handbag to retrieve the money and put it away. My stomach falls to the floor as I scrabble through hair clips and crumpled tissues and sweet wrappers and stray coins and my fingers close on lining and emptiness and no cash at all.

I sit heavily on the kitchen chair and stare out of the window at the darkness and my own pale face reflected there in the glass, my stooped shoulders. Shocked. Defeated. I feel sick. I can see it. The printed-off statement. Then the steady whirr and churn and the wad of money, the stash of two hundred and fifty pounds, sitting there in the mouth of the machine, waiting to be taken.

I look down at my fingers, grasping each other there on the table, my knuckles whitening. Rosie’s scream. The looming homeless woman. My mouth trembles. I know exactly what I’ve done. I’ve left it there. Two hundred and fifty pounds, sitting pretty for the next person to take. It isn’t just money. It’s their presents. It’s food. It’s Christmas.

Somehow, I manage to shake myself into motion.

‘Alex. Five minutes. Please. Just don’t move. OK?’

He doesn’t even lift his eyes, miles away in his game. He won’t budge. I can get away with it as long as Rosie doesn’t wake up.

I run down the stairs and out into the street in my still-sodden coat, hair flying. Rain, thick and heavy now, freezes my cheeks. Please God, please let it be still there. Please. I need that money. I really do. Not for me, for them.

It won’t be. I know that, even as I run. My breathing is hard and jagged with panic. Hours have passed. Dozens of people will have used that machine since then. I’m sure there was someone right behind me who could have taken it. But I must try. I must look. Already I’m thinking: Maybe if I called the bank first thing, they could check their security cameras, see who took it, and trace them, somehow.

The wind hits me as soon as I round the corner and turn into the high street. The pavement gleams wet, reflecting the garish colours of Christmas lights and decorations in pubs and bars and restaurants. Smokers huddle in doorways with their collars up against the weather. Dark ranks of commuters walk quickly with their heads down, heading home from the station, their hands deep in pockets, blocking the way. I dodge through them in panic, bumping shoulders, as if another minute might be decisive, as if I might catch someone in the act, their hand c. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved