- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

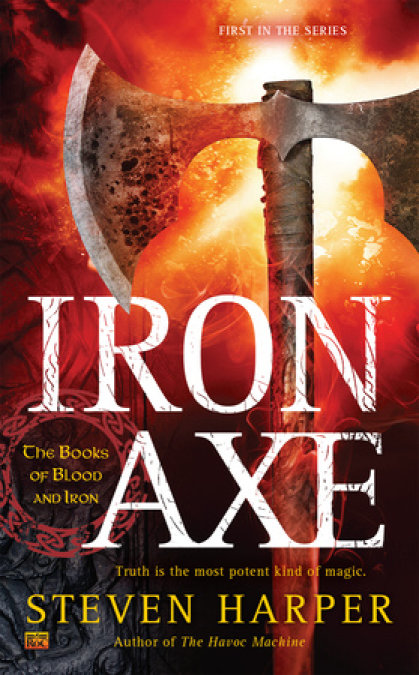

In this brand new series from the author of the Clockwork Empire series, a hopeless outcast must answer Death’s call and embark on an epic adventure....

Although Danr’s mother was human, his father was one of the hated Stane, a troll from the mountains. Now Danr has nothing to look forward to but a life of disapproval and mistrust, answering to “Trollboy” and condemned to hard labor on a farm.

Until, without warning, strange creatures come down from the mountains to attack the village. Spirits walk the land, terrifying the living. Trolls creep out from under the mountain, provoking war with the elves. And Death herself calls upon Danr to set things right.

At Death’s insistence, Danr heads out to find the Iron Axe, the weapon that sundered the continent a thousand years ago. Together with unlikely companions, Danr will brave fantastic and dangerous creatures to find a weapon that could save the world—or destroy it.

Release date: January 6, 2015

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Iron Axe

Steven Harper

The stable door creaked open and threw a painful square of sunshine on the dirt floor. Danr automatically flung up his free hand to shield his eyes. His other hand wielded a manure fork. A lone cow, kept in from pasture because of an injured leg, lowed nervously and shifted in her stall.

“Trollboy.” Norbert Alfgeirson crossed heavy arms in the doorway. His patchy brown beard stuck out short and prickly, like last year’s wheat stubble. “Get out here. Calf fell down the new well.”

He left without waiting for a reply, leaving the stable door standing open, showing a large tree inexpertly carved on the outside of it. The square of morning sunlight hung there like a sharp-edged shield. Danr set the manure fork down with a grimace. He was tall enough that his head rapped the ceiling beams if he didn’t take care, and his large hands bore the calluses of heavy work. His bare feet shuffled across the dirt floor, avoiding the bright square, though he was only putting off the inevitable. At the door, he lifted a battered straw hat from a peg and clapped it over wiry black hair, then screwed up his face, touched the tree, and stepped outside.

Sunlight slapped him hard. A dull ache settled into the back of his wide brown eyes despite the shading brim of the straw hat, and he squinted down at the ground, unable to give the clear spring sky even a glance. His wide-set toes clenched at the bare earth of the barnyard. The stories said sunlight turned the Stane to stone. Danr didn’t quite believe that, but if the sun caused this much discomfort to someone whose mother was Kin and whose father was Stane, he could understand why the Stane supposedly hid under the mountain during the day.

“Over here, Trollboy!” Norbert called. He was the eldest son of Alfgeir Oxbreeder, the enormously successful herder of cattle and sheep who owned the farm where Danr was currently a thrall. “Move! I don’t want this calf to break something because you dawdle.”

Danr straightened his back and strode across the barnyard, away from the cool, inviting depths of the stable. Outside, the crisp, fresh air of spring rolled down the western mountains, bringing with it smells of flowers and new leaves and just a hint of snow from the heights. Alfgeir’s generous herds lowed in stone-bound pastures in the distance, side by side with recently planted fields. The farm was in the lull of late spring, when calving, plowing, and planting were over and the season’s first haying had not yet begun, so there was time for other work, such as repairing thatch, reinforcing fences, and digging a new well for the cattle. Norbert was standing at the latter, hands on hips. So far the well was nothing but a hole in the ground. A formidable pile of earth and rocks stood nearby, and Danr knew it would be his eventual job to move it. From below came a faint bawl.

Danr sidled up to the well, slumping his shoulders and hunching over out of long habit, though it did little to disguise the fact that he had a full head of height on Norbert. His shoulders were broader, his legs sturdier, and his skin swarthier than anyone else’s on the farm. Danr’s long jaw jutted forward, giving him a pugnacious look, and his lower canines were just a little too long. He had no beard, but wiry hair was making progress over his chest and back. Although he had just turned sixteen, he already had a barrel chest and heavy hands with thick fingernails. He quickly outgrew the castoffs Alfgeir’s wife deigned to hand him, and his clothing was always patched and bursting at the seams. Compared to the fine wool tunics and well-cut trousers Norbert and his brothers wore, Danr was a shambling ragbag. His eyes, however, were wide and brown and liquid, and Danr’s mother always said they were his best feature, but they were always hidden under his battered hat. In any case, no one seemed to notice his eyes. They only noticed he was that troll boy.

“Well?” Norbert said.

Danr peered down into the well and was just able to make out the form of the calf at the bottom, some fifteen feet down. It was up to its knees in muck. Danr glanced at the calf pen, where the young cattle were kept apart from the rest of the herd during the day so they wouldn’t be injured by the larger animals, and knew what had happened. It had come to Norbert that morning to separate the calves from their mothers. He’d been careless and let one run after its mother, whereupon it had fallen into the well.

“It got away from the pen, then?” Danr asked, his voice low and quiet. Mother always said, “Be gentle, be soft-spoken, and people won’t think you a monster.”

“None of your business, Trollboy,” Norbert snapped, confirming Danr’s suspicions. “I should shove you down that well to join the calf and bury you with the rest of your filthy kind.”

The insults stabbed his gut. He’d been hearing them for sixteen years, and it seemed he should be used to them, but like the sunlight that pounded at his eyes, he never adjusted. Each one was a pinprick, or a knife cut, or a spear thrust, and some days it felt as if he were bleeding to death. Other days, the wounds turned his blood to lava, and he felt he might burst out of his clothes from the anger. Anger he could never show, not even once. Thralls didn’t get angry, no, they didn’t. It wasn’t fair or right, but when had the world ever been either, especially to his kind? His clothes felt tight and he worked his jaw.

“I’m sorry, Norbert,” Danr said, eyes down.

Norbert punched him in the gut. The air burst from Danr’s lungs, and white-hot pain slammed his stomach. He staggered, gasping. Anger flashed.

“I’m sorry, what?” Norbert snapped.

Danr had forgotten—Norbert had recently reached his majority. Danr forced himself to straighten, but not too much. Not so he was taller than Norbert. His gut ached. The monster inside him growled. He would have loved to punch back, but of course he did not. “Yes, Carl Alfgeirson.”

“What is it? What is happening now?” Alfgeir Oxbreeder hurried over. He was an older version of his son, with thinning brown hair, a bushier beard, and a heavy nose. His fine leather overtunic and thick wool breeches bespoke his success as a farmer, as did the silver buckles on his boots and at his waist.

“This fool let one of the new calves fall down the well,” Norbert said.

“What’s this, what’s this?” Alfgeir peered down the well. “Trollboy, if that calf is injured or killed, I’ll add more time to your bonding.”

“I—” Danr began, but Norbert made another fist behind Alfgeir’s back, and the words died. Norbert smirked. Anger beat a war drum inside Danr, and he ached to smash that smirk. He clutched with shaking hand at the small pouch with two splinters in it that he wore on a thong around his neck. Both pouch and splinters had belonged to Danr’s mother, the only legacy she had left him.

“They expect you to be a monster,” Mother said. “Don’t give them satisfaction.”

Danr closed his eyes, trying unsuccessfully to make the anger and resentment disappear. His father was a troll, his mother a human, and for that terrible crime, both he and his mother had been banished to the edges of village society. Carl Alfgeir Oxbreeder had reluctantly agreed to accept Mother as a servant in his hall, but caring for Danr had brought expenses that had quickly put her in Alfgeir’s debt. Before Danr’s fifth birthday, he and Mother had both become thralls to the Oxbreeder farm, one step above slaves. No amount of hard work kept them fed and clothed without more debt, thanks to Danr’s enormous appetite. Danr continued his grip on pouch and thong. It was unfair, but that was how the Nine ran the world. It didn’t matter what a thrall thought. He told himself that over and over, trying to make himself believe it.

“I’m sorry, Carl Oxbreeder,” he said at last.

“You’ll have to pull it out,” Alfgeir said. “As the saying goes, ‘The price of foolishness is hard work.’”

“I can’t do it alone, sir,” Danr pointed out. “Norbert will have to help.”

Norbert’s face grew red and he drew back his fist again, but Alfgeir stepped between them. “Let’s just get that calf out.” Alfgeir turned to Norbert. “So, howdid it fall in, then?”

He had already asked that, and it was clear he was giving Norbert another chance to come clean. Danr looked sideways at the young man. At eighteen, Norbert was only two years older than Danr, and when they were kinderlings, Danr had followed Norbert around like an oversize puppy. They had played Troll-in-the-Wood (Danr was always the troll) and fished in the brook and built a castle out of logs and stones. People called Danr Norbert’s pet, and they chuckled indulgently. But as they grew, Norbert became less interested in games and more aware of Danr’s status as a thrall—and a troll. These days it was as if they had never been friends and were instead a breath away from a blood feud.

Norbert ran his tongue around the inside of his cheek, and Danr held his breath. It would be such a fine thing if Norbert, just this once, would be his friend again, like when they were boys.

“I told you,” Norbert growled. “It’s Trollboy’s fault.”

Alfgeir sighed. Danr could see that he knew the truth, but he wasn’t going to side with a troll. “All right. On your head be it, Trollboy, if the creature’s injured.”

The calf bawled again, its voice barely audible above ground. Alfgeir took up a coil of heavy rope. “Climb on down.”

“Me, sir?” Danr said in surprise. “I thought you wanted me to pull it up.”

“I’m not climbing down there,” Norbert scoffed. “It’s muck to the knees, and these boots are almost new.”

Danr didn’t bother to protest. There was no point. Instead he squatted at the edge of the well and lowered himself into darkness, where he hung by one hand for a moment with easy strength before he let go.

The floor of the well and the bawling calf rushed up at him. Danr managed to twist and land beside the calf with a great splat in the mud at the bottom, though his jaw came down across the calf’s back. His teeth crashed together and he saw stars.

“You didn’t hurt the calf, did you?” Alfgeir demanded from above.

“No, Carl Oxbreeder.” Danr spat out a mouthful of blood, then pushed himself upright in the cool darkness. The wild-eyed calf bawled, and the sound boomed against the earthen sides of the well. It was actually nicer down here, despite the mud. Danr felt more at ease when he was surrounded by earth or in an enclosed space. He supposed it was his troll half speaking. The pain in his jaw faded somewhat. He scratched the calf’s neck and ears.

“You’re a pretty one,” he murmured. “Everything’s fine now. We’ll get you out, no need to worry.”

The calf calmed. It was covered in mud. Danr sniffed the air. The only way to clear cow manure out of a well was to let the water sit untouched for several months, and that would be disastrous, especially if Alfgeir took it into his head to add the time to dig yet another well to Danr’s bonding. But he smelled nothing. That was a small blessing, thanks be to the Nine. He looked up. Even when it was full day above, the sky always looked velvet dark from the bottom of a well. Danr had no idea why. He could even see stars. The fleck of brightness that was one half of Urko shone directly above him. The star that was Urko’s other half had moved just into the well’s horizon, ready to join with its opposite. Urko, the traitor Stane who joined the Nine Gods in Lumenhame, and had then been sliced in two by his brother Stane for his trouble. Now his right half lived in Lumenhame with the Nine and the left half lived in Gloomenhame with the Stane, and each side thought the other half spied for it. Only once every hundred years did they rejoin, and the two stars showed it in the sky.

“Where does Urko really live?” Danr asked when Mother had first told him that story. “With the Stane or with the Nine?”

“The story doesn’t say,” she had replied. “I suppose you have to decide for yourself.”

The knotted end of a rope hit him in the face. “Let us know when you’re ready, Trollboy,” Alfgeir called.

With a sigh, Danr set to work tying the rope in a harness around the calf. It wasn’t easy in the narrow, wet space. Mud squished up to Danr’s shins, slowing him further. The calf struggled, and more than once Danr had to stop work to calm it.

“What’s taking so long?” Norbert shouted down at him. “You’re dawdling on purpose to get out of real work.”

Danr ground his teeth and kept at it. The knots had to be done just right. If they came undone, the calf might fall on Danr and injure itself. His hands, soaked in muddy water, grew cold, and the rope became stubborn beneath his fingers. The calf continued its restlessness. At last, however, Danr had it in a rough harness.

“Ready!” he called, and tugged on the rope. It tightened, and the calf came free of the mud with a sucking sound. A surprised expression crossed its face as it rose toward the stars like a strange sacrifice. It reached the top, where Alfgeir and Norbert hauled it to safety.

Danr waited a moment, and when nothing was forthcoming, he called up, “Could I have the rope?”

Norbert poked his head over the edge. “We’re undoing these stupid knots you tied. Anyway, you’re too heavy. Climb up yourself.”

The monster snarled inside him again. Danr clutched the pouch at his neck. His mother’s soft voice always came back to him better when he did. “Don’t give in. Don’t give them an excuse to hurt you. Don’t let the monster out.”

“Yes, Mother,” he whispered.

He dug hands and feet into the sides of the well, his stony fingers biting into the stiff earth, and climbed toward the upper world. It was hard work. All his strength was in his arms and legs, but this used his wrists, and fiery aches burned in his hands by the time he reached the top. Gasping, he grabbed the rim of the well to haul himself over the top.

“I’ll teach the troll some respect, Father.” Norbert stamped on Danr’s fingers. More pain lanced through Danr’s hand. He let go with a yelp and landed heavily in the cold mud.

“Norbert,” Alfgeir said mildly at the top, “I don’t want you abusing the thralls this way. If you injure him, he won’t be able to do his work.”

“Sorry, Father.” Norbert didn’t sound sorry in the least. “I did make him get the calf out.”

“Good work, that,” Alfgeir said.

Danr levered himself out of the mud, worked his jaw back and forth, and set himself to climb again. There was nothing else to do.

When he finally pulled himself dripping out of darkness, the sunlight slashed his eyes and drilled through his skull. His hat was gone, lost below. He grunted and tried to shield himself with one arm, but the sun’s rays thrust sharp pain straight through him.

“Where’s your hat?” Alfgeir tutted. “Honestly, Trollboy, you can’t keep track of even the smallest thing. Here.”

He laid his own broad-brimmed hat on Danr’s head, and the pain abated somewhat. “Thank you, Carl.”

“I’ll add it to your bonding,” Alfgeir said. “As the saying goes, ‘A worker is worth his wages, and the wages must be worth his work.’”

Danr touched the brim of the hat. It was old and battered and too small for him, and he had the feeling Alfgeir would add the price of a brand-new hat to his bonding. But he only said, “Yes, Carl Oxbreeder.”

“Go wash up,” Alfgeir said. “And then I want you to run an errand.”

Danr blinked. An errand? That was unusual. Errands were choice, easy jobs that granted a chance to leave the farm for a bit. Danr was never chosen to run errands. He always did heavy or smelly work, like cutting stone or dragging trees or spreading manure on the fields.

“Yes, Carl,” he said, letting himself feel a little excited. Maybe today wouldn’t turn out so bad after all. He trotted across the farm toward the main well.

Alfgeir’s farm sprawled at the foothill bottoms of the Iron Mountains, meaning no one lived above them and there was plenty of free pasture in the hills for cows and sheep while Alfgeir’s family and thralls farmed the flatter land below. Because Alfgeir was wealthy, his long, L-shaped thatched hall stood apart from the stables, unlike poorer farmers who attached animal housing to their homes for the added warmth. There was even a separate hall for the servants and thralls across a courtyard paved with mountain stones. Danr, however, lived in the stable, which was an enormous longhouse shaped like a giant log sunk into the ground. The building was less than three years old—the original had burned down two summers ago. Fortunately Danr had managed to get most of the cattle out, and only six had died. This hadn’t stopped Alfgeir from blaming Danr for the entire incident and adding the cost of the lost cows and a new stable to Danr’s debts. It didn’t matter to Alfgeir that the new stable was almost twice as large as the old or that Danr had done the work of five men during the construction—Alfgeir said Danr’s debt was for the full cost of a new stable. It seemed to Danr that his debt should have been for the cost of rebuilding the original and Alfgeir should have shouldered the difference for a bigger one. But Danr kept quiet. He could have taken his case to the earl—even a thrall had rights—but then he thought of facing all those staring eyes in the public arena. And how likely was it that the earl would rule in favor of a troll? So Danr had silently accepted the additional debt and with it, the burden of anger whenever he thought about the new stable walls.

The farm’s well was equipped with a windlass and an enormous bucket that only Danr could lift when it was full. He hauled it dripping from the depths and simply poured it over himself, repeating until the water ran clear. His ragged clothes were the only ones he owned, and he went barefoot even in winter, so he had nothing to change into. At least he would dry soon enough in the hurtful spring sunshine.

Hunger rumbled in Danr’s belly. He sighed. He was almost always hungry, and whenever he ate more than a grown man, Alfgeir added the difference to his bonding, which meant Danr had to do extra work to have it removed, which in turn made him hungrier. It was a spiral he didn’t know how to break. Perhaps today he could slip away during the errand and go fishing. A salmon or even a trout, spit and roasted over a little fire, would go a long way in quelling the eternal emptiness inside him.

A shrill whistle caught his attention. Alfgeir was waving to him from one of the paddocks near the stable. Danr clapped the ill-fit hat back on his head and lumbered over. A young bull, barely into adolescence, was tied in the paddock.

“Take this animal to Orvandel the fletcher,” Alfgeir said. “He lives on the outskirts of Skyford, and I owe him a debt. If you hurry, you can make it to his house and back before dark.”

Danr eyed Alfgeir uneasily. A chance to go into the city was definitely a choice errand, something Alfgeir’s sons would fight over. Why was Alfgeir sending Danr? The offer rang false.

“Are you sure you don’t want to send Norbert, Carl Oxbreeder?” he temporized. “Or Tager? They might—”

“I didn’t ask your opinion, Trollboy,” Alfgeir said in a deceptively even voice. “I gave you an order.”

He turned on his heel and stalked away.

Danr looked after him for a moment, then shrugged and lifted the handle on the gate. The bull lowed at him. On closer inspection Danr realized it was not a bull but a steer, newly castrated. The animal was brown and just came up to Danr’s waist. Bones showed through skin, and Danr recognized it—the animal had recently recovered from a winter illness. This was repayment for a debt? The steer bawled again, and Danr reached out with a big hand to scratch the places where its horns would one day grow. It closed its eyes contentedly. Oh well. This wasn’t his decision, and Alfgeir had handed him a chance to escape the farm for a few hours on a fine spring day. Why question it? Danr took up the steer’s rope, and a few minutes later, they were both on the rutted road that led toward the city of Skyford.

The farm receded behind him, and the steer seemed content to follow without being coaxed or hauled. Trees lined the roads, forming boundaries between farms. Men and boys followed herds of cows around the fields, and their voices mingled with birdsong. Green grass had already filled the space between the ruts in the old road, and it was soft under Danr’s feet. A good mood crept quietly over him, like a dog that had been kicked away but still wanted to please. Maybe one day Norbert would trip over his own feet and fall into a pile of manure, and Danr would be there to see it. Norbert would push himself upright, brown cow shit staining his beard, and everyone around him, including Danr, would enjoy a good, long laugh. Then Danr could dump cold water from the well over him, again and again and again. How would Norbert like that?

Danr had fallen so deep into fantasy that he was completely unprepared for the hooded figure that rose out of the undergrowth beside the road. The steer bellowed in alarm and tried to flee, but Danr tightened his grip on the rope and the steer jerked to a halt, almost twisting its head to the ground. Danr didn’t budge. The figure’s clothes were little more than rags and were bundled in awkward layers. It stepped out onto the road, a basket in one hand. A bit more gladness grew in Danr’s heart, and he grinned a greeting.

“Aisa,” he said. “I haven’t seen you in days. You scared my steer.”

“Apologies.” Although the sun was quite warm, the low voice that drifted from the hood was muffled by multiple layers of scarf. “I was gathering greens and saw you coming down the road.”

“I’m taking this steer to Orvandel the fletcher in Skyford,” Danr told her proudly. “Alfgeir owes him a debt. Walk with me?”

“For a bit.” Aisa’s words carried an accent, exotic and exciting, though she had never said where she came from. All Danr really knew about her was that she was a couple of years older than he was, she had been a slave to the elves in Alfhame for something like two years, and now she was a slave to a man named Farek. Well, he knew that, and that seeing her always brought a little flutter to his heart, even though she never went anywhere without all her clothes wrapped around her. The most Danr had ever seen was a pair of brown eyes above a heavy scarf. It was enough.

“How does Mistress Frida treat you?” Danr asked as they walked.

“As she always has,” Aisa replied, and changed the subject. “I came down to warn you.”

Danr halted so quickly the steer bumped into him from behind. A little ball of tension turned cold in his stomach. “Warn me? Of what?”

“News just reached the village that the farm of the Noss brothers was attacked last night. House and stable were destroyed, and both Oscar and Olaf are dead.”

Danr swallowed. The village lay between Alfgeir’s farm and Skyford. Like Alfgeir, Oscar and Olaf Noss ran a farm that butted up against mountain wilderness. Every year they talked about expanding, but they never did, and their talk had become a running joke in the village.

“Why do you need to warn me?” he asked, though he had a feeling he knew the answer.

“It is rumored,” Aisa said slowly, “that someone found enormous tracks among the ruined buildings. Troll tracks.”

CHAPTER TWO

Acold finger ran down Danr’s spine, bump by bump. “By the Nine,” he whispered.

“You know who they will blame,” Aisa said.

His hand tightened around the halter rope. Oh, he knew. He knew down in the place where his guts coiled inside his belly. He also knew the only good way to Skyford took him through the village and past a hundred hard and angry eyes. True, he could leave the road, but that would send him tramping through freshly planted fields and earn him more anger.

Maybe he should just go back to Alfgeir’s farm. But no—Alfgeir had made it clear that he was to take the steer to Orvandel in Skyford, and Alfgeir would be Vik-all furious if Danr returned, errand uncompleted. No matter what he did, someone was going to be angry at him. The Nine were laughing while they pegged his tenders to a wall. It seemed to be his lot in life.

With a heavy sigh, he wrapped the rope around his knuckles, straightened his back, and tromped resolutely forward. It was what you did, even when it hurt.

“What are you doing?” Aisa hurried to catch up. “Trolls have not come down to the village in living memory. They all believe that you have somehow brought them down upon us.”

“Yes, and?” he growled. “I should at least get my work done in the bargain.”

“They may come after you. They will come after you.”

“And they’ll throw things, I suppose, but I have a thick skin.”

“The skin around your body is thick,” Aisa said, falling in beside him, “but what about the skin around your heart?”

There was nothing to say to that, so Danr trudged on in silence, every step taking him closer to the village. His earlier fine mood was a wreck. After a moment, Aisa reached over and gave his forearm a little squeeze. Her fingers left a warm print on his skin. He didn’t slow down, but he felt a little better. A lot better. Aisa could do that for him, and she seemed completely unaware of how incredible this small power was for him. She made his life bearable, even happy, though he couldn’t find it in himself to tell her. A troll simply didn’t have the words.

Farek had bought Aisa from a slave dealer who trucked with the elves from Alfhame in the southeast. Something about the elves forced humans to adore their masters. Human slaves needed their elven masters the way a drunk needed ale, and the worst punishment a slave could endure was to be sold away from the keg.

Aisa had never said what awful thing she had done that made her owner decide to punish her with exile, and Danr, sensing the pain involved, had never asked. He could never cause Aisa pain.

Everyone in the village, however, knew exactly why Farek had bought Aisa, and everyone knew what he did with her in his stable at night, and everyone knew that Farek’s wife, Frida, hated him for it. Frida couldn’t do much to Farek, so her red and cruel anger found the next best target—Aisa herself. Danr knew without being told that Aisa wrapped herself up to hide the bruises, and the thought of those bruises made Danr angrier than anything Norbert might do, and he had to work hard indeed to keep his temper to himself whenever he saw Farek in the village. It was one of many reasons he kept to himself as much as possible.

They crested a slight rise, and the outer ring of village houses came into view. They were similar to Alfgeir’s—long, rounded structures half-buried in the ground as if huddling for warmth, their wattle-and-daub walls covered in a blanket of whitewash. Every door had a tree carved or painted on it, some expertly, some crudely. The village was too small to have a name. Ordinary gossip got around quick, while bad gossip rushed fast enough to break its own neck. If Aisa knew about the troll tracks in the Nosses’ flattened house, everyone knew. More tension tightened Danr’s stomach and his breathing came faster. Aisa gave his arm another soft squeeze and left the road. He knew why. Being seen with him would give Frida another excuse to reach for her birch rod, and there was no reason for both of them to suffer. The road felt empty with her gone.

He held his head high as he took the steer through the outer ring of houses. The road widened and dropped into ankle-deep mud that sucked cold at his feet. The usual chickens and pigs rooted in the byways between the house

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...