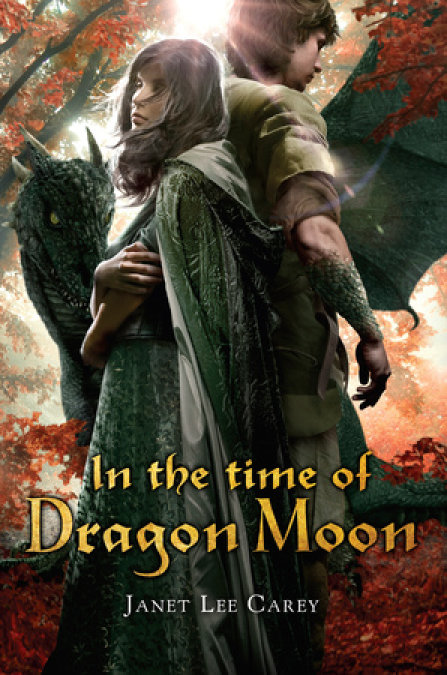

In the Time of Dragon Moon

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A rich medieval fantasy novel from an author whose work has been called “TRULY ORIGINAL . . . FANTASY AT ITS BEST.”

A perfectly crafted combination of medieval history, mythology, and fantasy, set on Wilde Island, featuring Uma Quarteney--a half Euit and half English girl, who has never been fully accepted by her Euit tribe--and Jackrun Pendragon--a fiery dragonrider with dragon, fairy, and human blood.

On the southernmost tip of Wilde Island--far from the Dragonswood sanctuary and the Pendragon Castle--live the native Euit people. Uma wants to become a healer like her Euit father. But the mad English queen in the north, desperate for another child, kidnaps Uma and her father and demands that he cure her barrenness. After her father dies, Uma must ensure that the queen is with child by the time of the Dragon Moon, or be burned at the stake.

Terrified and alone, Uma reaches out to her only possible ally: the king's nephew Jackrun, a fiery dragonrider with dragon, fairy, and human blood. Together, they must navigate through a sea of untold secrets, unveil a dark plot spawned long ago in Dragonswood, and find a way to accept all the elements--Euit, English, dragon, and fairy--that make them who they are.

Release date: March 24, 2015

Publisher: Kathy Dawson Books

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

In the Time of Dragon Moon

Janet Lee Carey

CHAPTER ONE

Euit Village, Devil’s Boot on Wilde Island — Falcon Moon, April 1210

Knife in hand, I crouched under the willow. Father’s dragon skimmed over the river, her crimson scales blazed blood red across the surface. Her searing cry rang through the valley. Dragons live more than a thousand years; their turning eye sockets allow them to look forward and back, seeing past and future, patterns in time we humans can never see. My eyes were fixed on smaller things.

Today he will tell me. Today I will know.

I took my knife to the ends of my hair. Crow-black strands in my hand, red-toned where the morning sun struck them. The auburn from my English mother was nearly swallowed by the black, but I could not hide what I was: a girl, a half English. Under the willow, I covered the strands with soil. I’d buried much in this secret place.

Tying back what remained, I went to wash Father’s medicine pots in the river.

“Uma!” Ashune raced down the muddy riverbank, her baby screaming in her arms. “Help him please!”

I scrambled ashore, dripping. “What’s happened?”

“A bee stung him. And he . . . look!” She pulled back Melo’s blanket. His waving arm was red and swollen as a rotting plum. I gripped his tiny wrist. He wailed as I pulled the stinger out.

“Was he stung in other places?”

“No, just here.” Her eyes were wide. “Why is it so swollen?”

I heard a wheezing sound between cries. His throat was swelling shut. “It’s a bad reaction.”

Ashune hugged him to her chest. “He needs medicine, Uma.”

My father, the Adan, was the only healer in our village. He’d gone to Council Rock to speak to the elders on my behalf. I didn’t expect him back for hours.

Melo coughed, shuddered.

“Help him, Uma. Please!”

“I can’t. Only the Adan can—”

“You’re the Adan’s apprentice,” she cried. “Look at him. He can hardly breathe!”

“Wait here.” I raced uphill to the healer’s hut and ran my hand along the shelves. This could cost me my apprenticeship. But how could I let Melo suffocate? All Father’s hard work bringing Melo into the world would be in vain if he died, and Father was away just now because of me.

I grabbed the elixir I’d seen Father use and a jar of sooth-salve.

Little Melo was turning blue by the time I reached him again.

“Hold his mouth open, Ashune.” Holy Ones, help me help him. Our law was clear. No one but the Adan could heal the sick, but still I spilled three green drops on Melo’s tongue. So the law is broken in drops, I thought.

“Swallow it, little one, swallow.” Breathe. The world grew silent as I listened to his ragged sounds between each cry. I could not hear the wind in the branches, the rushing river; only Melo struggling for air.

“It’s not working,” Ashune cried.

“Pray,” I said. I dosed him again, gently ran my fingers along his throat to help him swallow.

Melo was conceived thanks to Father’s magnificent fertility cure. Breathe. Our small Euit tribe needed every child. Live.

Melo squirmed, sucked in air, and shuddered all over. He kicked in his blanket. Was the soft brown color coming back to his face? I gripped the elixir jar tight, watching him. He took a few more breaths that didn’t sound thick or strained. And with his breathing, other sounds returned—the breeze in the willows, the singing river.

“Holy Ones, you did it.” Ashune wept with joy, rocking her boy between us. She was a year older than me, eighteen when she bore Melo. It wasn’t an easy labor.

I wanted to hold him too: weep and rest my cheek against his downy head, but I had never seen my father do such a thing when he cured the sick. A healer kept his dignity. And his distance.

I rubbed the sooth-salve on Melo’s swollen arm, scooped out more of the ointment, and wrapped it in a leaf. “Rub this twice more on him today. Hide it in between.”

Ashune took the leaf.

“Tell no one you came to me,” I said.

“I won’t tell.”

She looked at me, silent a moment. The word Euit means “family.” Our chieftain said we were one family. We all belonged. It wasn’t that simple for me. Ashune’s mother caught us playing by the river together when I was six, she seven, and told her to keep away from the half English. I looked more like Father than Mother, with his skin, high cheekbones, and dark eyes, but that did not count for much back then. I knew I didn’t belong. Not long after that, I buried my girl’s clothes under the willow, left my mother’s side, and went to serve my father the Adan to become a person of value in the tribe.

Ashune rocked Melo. “Thank you, Uma.” Since the day her mother dragged her off, things had been awkward between us.

“I have washing to do,” I said, glancing down at the pots. She hesitated, but I waved her on. “Go. Melo should sleep.”

Ashune’s colorful woven skirts brushed past clumps of wild iris as she climbed back up the riverbank. Melo made a contented cooing sound. He was one of just five infants born to us after nine years of emptiness and waiting. No one knew why our women had stopped having children. Had some plague infected us? Had something entered our food or water? We still didn’t know, but after years of seeking, my father found the plants he needed to make his fertility potion.

I’d held Melo the night he was born. Today I’d cured him—maybe even saved his life. My heart swelled, tightening the binding cloth around my breasts as I watched Ashune heading back to the village.

In our family hut just before dinner, Mother gave me a new belt with twelve red dragons woven in it. Her green eyes shone with delight above her freckled cheeks. The belt was her wordless way of telling me she expected good news when Father came home. I clung to the belt, admiring her fine craftsmanship. Hoping. More than that, believing she was right.

Mother said, “I wove some of my hair into each dragon.” She’d done the same with Father’s sixteen-dragon belt. Her auburn strands gleamed in the red wool, adding vibrant orange tones. I hugged her before cinching it around my waist like a power charm, then stepped outside to wait for the Adan. Today he will tell me. Today I will know.

In the hut, Mother sang to herself as she grilled the tuki peppers, Poppies and roses in her hair. She is queen of the May. Oh sing to her gladly and never sing sadly, she is the light of our day. She loved the English ballads from her childhood, but I was no queen of the May.

I looked beyond the cone-shaped rush roofs to the thick forest climbing steeply beyond the village and felt a small flutter of excitement as Father came down the trail with his herbing basket.

I knelt and touched the Adan’s feet with reverence before he entered our hut. At dinner I could hardly eat around all my unasked questions. Father, for his part, seemed to be chewing his thoughts. I’d served as his apprentice for ten years, but no girl has ever become an Adan. If the chieftain agreed today, I’d be the first.

Father hadn’t accepted my help that first year; still I persisted. He did not like girlish chatter, so I was silent. He did not like weakness, so I stayed strong. He was never ill, so I was never ill—or if I was, I never let him know it.

I rubbed the old scar bisecting my palm. Tell me, Father. He bit. He chewed.

“I spoke with the chieftain about you,” Father said at last, dusting the crumbs from his mat. “Your path is chosen, Uma.”

I hooked my thumb through my new belt, tugging the flying dragons tighter against my waist, circling Uma Quarteney. Healer. Adan.

Father said, “You are to marry the hunter Ayo Hadyee in the time of Fox Moon.”

My stomach seized. “M . . . marry? But my healer’s path . . . Didn’t you ask the chieftain, Adan?”

“You have been a great help to me, Uma, but I’ve put things off too long. I should have started training a male apprentice sooner.”

“What male could learn as much as I already know?”

“Mi tupelli,” he said softly.

Mi tupelli—my lad. The nickname raked my heart. “Don’t call me that. Not now!” His brows flew up. I’d never raised my voice to him before.

“It’s been decided,” Father said. “As a female, you can be an Adan’s helpmate. Never a healer.”

“Then why this?” I tugged my tunic down to the fox mark below my collarbone. “Why did you burn the pattern of my Path Animal on my skin if I was never meant to be a healer?”

Such burns were reserved for warriors, elders, healers. I gloried under the excruciating pain the night he pressed the tip of the hot wire to my skin again and again until the tiny fox was complete. I took it as a sign I would become an Adan. A healer would not be shunned for being half English. A healer is needed. A healer belongs. And more than anything, I’d wanted to belong.

Father took Mother’s hand. “Paths can change directions, Uma. I know you dreamed of more, and for a time I also thought . . . but our laws guide us. It’s good for you to marry. You know how much we need children.”

“I’m needed as a healer. People have learned to accept me as your apprentice.” An acceptance that was hard-won. “I know how to help you treat our women with Kuyawan so they can have the children we need. Who else can do that?”

Father’s mouth was a stern line.

I said, “Does Ayo even want to marry a half English, a girl who does not cook or garden or weave, a girl who has dressed as a boy most of her life?” The look on Father’s face told me what I needed to know.

Mother said, “I understand how you feel, Uma.”

“No, you don’t.”

“Believe me, I do. I know how hard you’ve worked. I’ve seen it. It hurt for me to give up my midwife practice and come here to live a different life, learning Euit ways so I could marry your father, but I did it.”

“You did it because you love him! I don’t love Ayo Hadyee.”

“You can learn to love him, Uma. It’s what your father wants for you.”

“No! It’s what you want!”

I shot out the door. I didn’t know why I raced to the healer’s hut until my hands were on the jars I’d washed that morning, until I was hurling them across the room, breaking them against the wall.

“Uma, stop.” Mother came in, took my hands, and pulled me back outside. People had poured out of their huts, curious to see where the crashing sounds had come from. “Go back to your meals,” I shouted. “Leave us!”

A hot wind scoured us from above. Father’s red dragon, Vazan, must have heard the sound of breaking jars from the healer’s hut. She dove from the clouds and roared a warning fire over our heads. I pushed Mother away, wanting to scream fire right back at Father’s guardian. But no human breathes fire.

Or so I thought then.

The next day, after convincing Father to let me work beside him until Fox Moon came, I helped him attend my uncle Sudat, who’d accidentally cut his leg while skinning a goat. I was soothing my uncle with a smoking sage bundle as Father stitched the wound, when I heard horses’ hooves and shouting in the distance.

Father kept chanting as he stitched. The far-off shouting turned to screams. The Adan did not allow himself to be distracted, but I peered out the door.

“Adan,” I screamed. “King Arden’s army!” I’d not seen the king’s soldiers since I was small, when they’d burned our huts and forced us farther south. “They’re armed!”

A soldier raced up and slashed an old man’s neck right in front of our hut. Blood spurted onto the murderer’s boots and breeches.

Now people were running, scattering like goats frightened by a mountain lion. Two armed men burst into the healer’s hut.

“Are you Adan?” the taller one barked. Father looked at him. He did not say yes. He did not say no. But the soldier saw what Father was doing to mend my uncle’s leg. The shorter man grabbed me, shook the smoke bundle from my hand, and stomped it out with his boot.

“Are you the famous healer who cured infertile women?” the tall one asked. “Answer me!”

“Yes,” Father said.

Sudat groaned, “My leg.” His gash still gaped open. The soldier shoved Father aside and drove a dagger through my uncle’s heart, silencing him. I stopped the scream that came up my throat. It was like damming a river.

He turned his bloody blade on Father. “Pack all your medicines, old man. The queen of Wilde Island commands your presence.”

Father loaded his trunk. I watched the dagger’s point as if my eyes alone could keep Father alive.

The second soldier let me go. “Help him pack, boy. Stinks in here.” I did as I was told, wrapping the tincture jars, the fertility herbs we’d gone so far across the mountain to find. Father packed his herbal book and locked the trunk. He was whispering, praying to the Holy Ones. I was too sick with fear to pray.

The army encircled our village. Our warriors and the red dragons were away hunting. We were defenseless. Ashune hid in the trees with Melo. People ducked behind boulders, bushes, huts. The soldiers chained Father’s wrists and prodded him up the steps into the jail cart.

I raced up and jumped in the cart with him. Father pushed my shoulders. “No, Uma. Stay here with your mother.”

I gripped the iron bars so he couldn’t throw me outside.

A soldier jabbed me with his sword, slitting my pant leg where I crouched, clinging to the bars. “What are you doing, boy?”

“I am the Adan’s apprentice. He needs me.”

They looped a cold chain tight around my wrists, chained Father’s ankles and mine, and shut the metal door with a clank. Then the army set out, their lead chargers stirring up choking dust.

Through a brown cloud I saw Mother run out from our hut, her red hair streaming behind her as she raced after us calling my father’s name, calling mine. “Uma, no!”

I gripped the bars, afraid, as two soldiers grabbed her arms, stopping her. But they did not put the sword to her throat.

For once I was glad she was not like the other women in our village.

For once I was glad she was English.

CHAPTER TWO

Journey to Pendragon Castle — Falcon Moon to Fox Moon, April to May 1210

It was a grueling three-week journey. Half the army followed the king’s son, Prince Desmond Pendragon, north out of Devil’s Boot. The other half had stayed behind, surrounding our village. The queen wanted Father alive, but what would happen to Mother and everyone we left behind? What would the army do to them? My anxious thoughts churned in rhythm with the cart’s relentless wheels.

On the third day, I felt a rush of warm wind. “Father, look.” Large red wings cut through the thin clouds above. His dragon, Vazan, had found us! Her muscled body spanned the length of seven horses; twice that again if you measured her snout to tail. She skimmed down on wings as large as mainsails. Men shouted, straining to control their frightened horses. I gripped the bars, hoping she’d roar fire, kill our captors, even as I knew she wouldn’t do such a thing. Reds abided by the dragon treaty. They no longer killed humans. Or ate them. But at least she frightened the king’s men. Father winked at me as the cavalcade fell apart, horses galloping this way and that ahead of us.

Mother had told me stories about the royal Pendragons whose blood was mixed with dragons. But on our journey north, I never once saw Prince Desmond Pendragon behave like a man with noble dragons’ blood. One night he staggered drunk to our cage. “You’re looking at your next Pendragon king,” he said. “Call me Your Royal Highness.”

“Your Royal Highness,” we said, dry-tongued with thirst. We’d learned to obey. We were whipped when we did not.

“I’d order you to bow, but you’re chained up, so.” He shrugged and laughed. “By God, you Euit dogs stink! As soon as Mother sees you and your boy here, she’ll realize you’re a fraud. Healing infertile women. Ha. That’s a joke. I bet you used your own prick, old man.”

He staggered off. Devil! His words dug a pit of shame so deep in me I could not show my face to my father.

We were rarely fed, but one soldier with a crooked nose secretly shared his rations with us. “Here, eat,” he said pushing bread through the bars one night, dried meat another. We learned his name was Sir Geoffrey.

Fox Moon was a silver bracelet in the sky the week we reached the northeast coast and saw Pendragon Castle rising tall and dark on the edge of a cliff.

The closer our rattling jail cart got to the castle, the more my chest tightened. I could hardly breathe by the time we crossed the drawbridge. Father saw my face and wrapped his large hands around mine. He had never done that before. I looked down at our hands in astonished wonder.

“You did not have to come with me, Uma,” he whispered.

“I did. I couldn’t let you go alone.”

Soldiers hauled us through the wide castle door, down a chilly torchlit hall, our ankle chains clanking, and forced us up spiraling tower stairs to a room on the second floor. The minstrel’s music dulled to a wary halt as they dragged us inside. Girls and women put down their stitchery and stared.

Queen Adela sat on an ornately carved high-backed chair, wearing a velvet gown as purple as fresh bruises. The color set against her pale skin brought out the sheen of her hair, dark brown with a few silver strands thin as spider’s silk. She was beautiful and severe.

Mother told me witches had attacked her when she was younger, putting out her eye with a poker. The fey folk fashioned her a glass eye to replace it. When she’d regained her strength, she’d sought revenge as a witch hunter. That was before she’d become the queen, but I saw ferocity in her still, or was that just my fear looking back at me?

“Leave us!” she commanded. A dozen ladies-in-waiting dropped their sewing on the benches and scurried out behind the musicians. Only one woman remained at the queen’s side.

She was even paler than the queen, if that was possible. A single blond strand poked out from under her shoulder-length veil. I was used to warm, brown skin. These two made me think of snow and shiver.

Four blue eyes appraised us as if we were strange animals the guards had just deposited on the floor. I knew we stank. I wanted to say, We do not bite, but knew better.

Father cleared his throat.

“Remain silent until Her Majesty addresses you,” said the woman. “You are filthy,” she added, flicking out a colorful lacquered fan and fanning the queen.

Queen Adela asked, “Is it true you helped infertile women, Adan?” Her blue glass eye glinted in the afternoon light. “Is it true that they bore children after taking your cure?”

“It is true,” Father said.

“Call me Your Majesty!” she growled. “Who had you whipped?” she added, eyeing the long ragged tears in Father’s shirt.

“Your son, Prince Desmond, Your Majesty.”

The queen stared down at her lap. “My son, my son, my one and only son,” she whispered in a singsong voice, pinching her velvet skirts and pulling them apart as if she’d lost her son somewhere in the folds.

“What’s that?” she said, glancing toward the empty alcove to her right where the musicians played when we’d first come in. “Take it away,” she said to the empty space. “The pudding causes upheaval to my stomach.” Then she went back to pinching her skirts.

I heard Father’s slow intake of breath. No one had warned us that this queen, who’d abducted us, whose army held our people captive, this fey-eyed, former witch hunter, was mad.

The woman who entered our tower room the next morning was the same elegant English one who’d stood by Queen Adela. “I am the queen’s companion, Lady Olivia,” she said. “I have come to welcome you on your first official day here at Pendragon Castle. You bathed?” she asked, sniffing the air, her delicate nostrils flaring. We had scrubbed as best we could and changed into the new, strange English clothing. (They’d stolen our clothes and burned them.) A stale odor still haunted the armpits of my used scribe’s outfit, but I liked the ink-stained sleeves. Father looked his part in his dark physician’s robes. At least we both still wore our dragon belts.

“Yes, we bathed, thank you,” Father replied, looking up from his worktable. They’d housed us in a tower chamber called the Crow’s Nest where the queen’s physicians had lived. The windows faced all four directions. I’d unlatched the iron grid work and opened them first thing to air out the room.

“That’s ‘thank you, my lady,’” Lady Olivia said, still hovering near the open door as if she might make a quick escape. “You must learn castle etiquette if you want to keep your life. You are called upon to help Her Majesty. She is desperate for another child. She gave a son to the king sixteen years ago now. It’s a queen’s duty to mother the king’s children. Many children,” she added, her sharp blue eyes on Father. “Her Majesty feels she’s failed her husband. Do you understand the importance of your mission?”

Father gave a single, stern nod.

“Her last physician displeased Her Majesty. He’s in the dungeon awaiting judgment. She’s executed physicians for their foul treatments that promised everything and did nothing.” Lady Olivia paused a moment. “I tell you this as a warning. She is not getting any younger.”

“I am the Adan,” Father said, head high. “I have the medicine she needs.”

“News of your miracle cure has spread far and wide. That’s why Her Majesty sent for you.”

You mean stole him.

“I hope for your sake there’s more to it than market gossip.”

I flinched. “My father is the best—”

“Hush, Uma.” He brushed his sleeve, removing her comment with a slow downward swipe of his hand. Father could do that. I couldn’t. Her insult entered my blood like venom.

Father turned. “Am I to treat the other condition?”

“The . . . other?” Lady Olivia looked behind her suddenly, checking to see we were still alone.

“We saw her refuse the pudding, my lady. How often does she speak to people who are not there?”

Lady Olivia crossed the room, her heels clicking with purposeful steps. “Listen, Adan. That is your name, isn’t it?”

“It is my title.”

“No one speaks of the queen’s . . . episodes. She is unwell, and gossip-mongering—”

“I am no gossipmonger, my lady. I plan to treat both maladies.”

She moved to the worktable, whispering, “If you have something to balance her mind, give it to her. But I warn you.” She looked around again. “Never talk about her moods with anyone but me. You understand, Adan?”

She left us, shutting the door behind her. Father took out his scale and weighed the huzana leaves he used for his fertility cure, his hands flying swift and sure as birds. Mine were shaking as I struck the flints and lit the brazier to seethe the queen’s potion. “What do you think Queen Adela will do with the physician in the dungeon, Adan? Will she execute him like she did the others?” I was thinking about us, about our future here.

“Be present with what you are doing, Uma.”

“How will you treat her . . .” What did she call them? “. . . her episodes, Adan?”

This made him stop and look up. “The English do not understand about balancing the four sacred elements of earth, wind, water, and fire in the body. What imbalance did you see in this queen, mi tupelli?”

“She is not balanced by earth, she has some fire.” I was guessing.

“The queen is ruled by wind,” he said. “Her scattered thoughts and phantom visions are caused by wind mind.”

I felt the barb of failure in my gut. “You will use earth element plants to ground her?” I said, still wanting to appear knowledgeable. He ignored my attempt.

“I need the water seething, Uma.”

I watched him work as I heated the water, steam ghosting between us.

“You are too anxious for what you want, Uma. Begin by wanting what you have.”

Father chanted the Euit plant names as he dropped kea stems and huzana leaves in the simmering pot. I decided to be present with what I was doing, and chanted with him.

Every plant has a name, and the name holds the secrets of its origin—the dreams the earth fed its roots, down in the dark underneath. The name awakens the plant’s healing powers. I knew the powers these plants held, the power to bring new life.

In the queen’s aviary, the Adan gave Queen Adela the curative. After questioning my father about its name and its efficacy, she drank it down, watching Father over the chalice rim.

When she finished, Her Majesty dabbed her lips with her kerchief, then tossed birdseed to her songbirds, causing a small winged riot in the cage as they fluttered down. I felt sorry for the birds. Mother loved birds, especially small, bright finches. She would never hold them hostage the way this queen did.

“I am a generous queen. I plan to free your village if your cure works, Adan. Give me a child and my husband’s soldiers will break camp and march north again.”

She held out her hand. Lady Olivia mouthed to Father, Kneel and kiss her ring.

I took a breath. My revered father knelt to the Holy Ones in prayer and he bowed to his red dragon, never to another person. I felt a small landslide somewhere behind my ribs as he stepped closer, bent his neck, and put his lips to the queen’s ruby ring. The stone was as red as a wound. It flashed when she withdrew her hand and held it out again, this time to me.

I fell to my knees. The landslide had already occurred, though it did not make falling to the floor any easier. The ruby was frigid, a smooth dead thing, only slightly colder than Queen Adela’s hand.

“My son told me the soldiers had to kill some Euit men to bring you here,” she said to Father when I stood and backed away again. “If your healing tonic works, I will be content and so will the king. The men will have died in a good cause.”

Sickness washed up my throat. A good cause?

We turned to go.

“Face Her Majesty as you leave her presence,” instructed Lady Olivia. “Head lowered, back out.” Yesterday the guards had hauled us out in chains; today we walked out backward.

Later in the Crow’s Nest, I attacked the rushes with a broom to sweep the fury out of myself over the butchery back in Devil’s Boot, over my uncle and the rest of the men these English were content to kill in their good cause.

CHAPTER THREE

Pendragon Castle, Wilde Island — Snake Moon to Whale Moon, June to July 1210

On the last nig

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...