- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

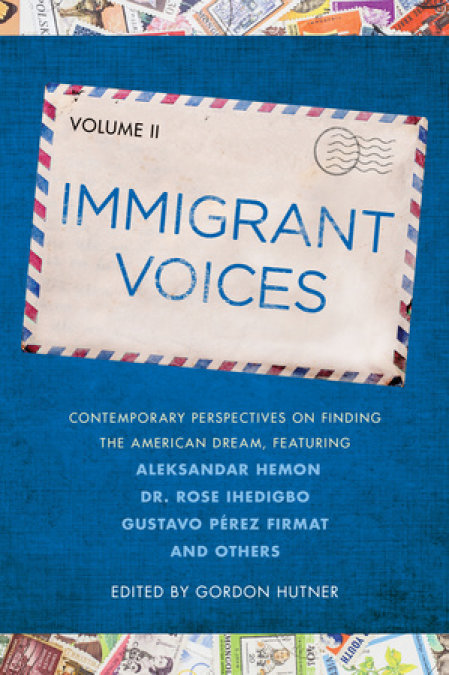

Synopsis

A compelling collection of essays providing a comprehensive vision of immigration to the United States in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries—the indispensable companion to Immigrant Voices.

Filled with moving narratives by authors from around the world, Immigrant Voices: Volume II delivers a global and intimate look at the challenges modern immigrants confront. Their stories, told with pride, humor, trepidation, candor, and a touch of homesickness, offer rarely glimpsed perspectives on the difficult but ultimately rewarding quest to become an American.

From the humorous experiences of Firoozeh Dumas, author of Funny in Farsi, to the poignant struggles of Oksana Marafioti, author of American Gypsy, this collection travels from Burundi to Afghanistan, Egypt to Havana, and Cambodia to Puerto Rico, to present incredible contemporary portraits of immigrants and illustrate that America is, and always will remain, a fresh and ever-changing melting pot.

Featuring Firsthand Accounts by

André Aciman, Tamim Ansary, H.B. Cavalcanti, Firoozeh Dumas, Gustavo Pérez Firmat, Reyna Grande, Le Ly Hayslip, Aleksandar Hemon, Rose Ihedigbo, Oksana Marafioti, Anchee Min, Shoba Narayan, Elizabeth Nunez, Guillermo Reyes, Marcus Samuelsson, Katarina Tepesh, Gilbert Tuhabonye, Loung Ung, Kao Kalia Yang

Release date: June 2, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Immigrant Voices, Volume 2

Gordon Hutner

INTRODUCTION

As a kind of birthright, Americans grow up with the idea that theirs is a “nation of immigrants,” and of course it has been and continues to be. But does this phrase have the same resonance in every generation or even every century? Questions about what kind of and how many immigrants we should have are now as controversial a subject as they have ever been in our past. For at every stage of the history of American immigration, our vigorous welcome of so many of the world’s tired and huddled masses was not something about which everyone agreed. Despite our cherished ideal that this country should be understood as a grand melting pot, there have typically been great detractors throughout our history who have challenged this faith in the vitality of an ever-diverse nation. Yet for all the resentment sometimes greeting newcomers, we should also discern the nation’s abiding passion for the potential growth that immigrants carry with them, whether they arrive here to meet a labor shortage or to escape persecution in their homelands or merely to join in the American pursuit of happiness.

A century ago and longer, immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Russia, Eastern Europe, and China were especially viewed as objects of suspicion. Immigration from Asia, the Middle East, as well as Central and South America, was, for many years, discouraged, even denied; the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese laborers for ten years, a law renewed in 1892, made permanent in 1902, and not repealed until 1943. A similar statute, the Asian Exclusion Act (1924), forbade immigration from India, Korea, and Japan as well as from the Middle East. And immigration from Africa was nearly as difficult.

What was behind this atmosphere of mistrust? It was less the case, as it is now sometimes expressed, that immigrants would create an undue demand on U.S. social services, largely because social services were not yet federalized in the early years of the twentieth century. Instead, nativist anxieties hinged on two kinds of fears: economic and social. The first focused on the conjecture that immigrants would eventually develop and control wealth and that it would be disposed according to their loyalty to their church, if they were Catholic, or to their homelands, especially if they were non-Europeans. Immigration was also imagined to threaten social stability, especially through racial and ethnic mixing, which would contaminate the American gene pool. This fear of diluting the nation’s northern and western European “stock” is a biological and sociological fallacy that has long been discredited, though one can hear it articulated even now. Compounding such concerns was the worry that immigrants would also import dangerous political ideas from abroad, such as views opposing capitalism and the presiding understanding of the nation’s democratic ideals. That so many of these despised immigrants were Catholics, Jews, and Asians further contributed to this America-for-Americans prejudice, an anxiety that politicians readily exploited.

Despite these worries, the story of the successful assimilation of a multicultural immigrant population is among the most brilliant chapters in modern U.S. social history. And these immigrants’ rise from generally low origins—during the rise of industrialism, they were much more often peasants than people with trades or professions—into the middle class is an epic tale that gives the phrase “a nation of immigrants” its meaning, perhaps even its glory. This tale is recounted time and again in the novels and tales that immigrants wrote about the challenges of achieving cultural citizenship. Perhaps even more popular were the first-person chronicles of coming to America and of becoming Americans. For one crucial way of conducting the argument over who can and ought to be citizens—and who should not—is found in the rich literary record that immigrants have left behind.

Such autobiographies are often written partly as accounts of how to flourish in one’s adopted country. So it is unsurprising that they often include practical lessons: say this; don’t do that; dress this way. But their more enduring value lies in how they also address the mainstream populace, readers who took up these memoirs both for the vitality of the stories they told and for keeping up with changes in the culture. Written as they are in English, these accounts specifically appeal to the host culture’s interests, while also advertising an author’s mastery of the language as a sign of successful assimilation. Explicitly and implicitly, these books present their authors’ case for belonging, as if to demonstrate for the audience of the native-born that immigrants have a great deal to offer and that they in their own way have a vast potential to make the U.S. an even better place. In this sense, such autobiographies are both personal documents—the story of my exemplary past—and public ones—an understanding of our nation’s shared future. If so much immigrant writing was spurred by the need to model how success in the U.S. might be achieved, they were also written to inform the native-born how to value the ordeals that immigrants endured, how to appreciate the achievements that they might tally, and how fully the belief in the virtue of the nation’s diversity will be rewarded.

Autobiographers probably don’t begin with this larger purpose in mind. They begin instead with the hope that their stories might be illuminating and entertaining. And they are. Their narrative form is often drawn from the bildungsroman, a tale of a protagonist’s growth and education. Such memoirs start with a figure who must navigate between the crippling marginality of present circumstances and the promise of the future. Typically, these narratives begin with the struggle to leave native lands, where the autobiographer faces more or less intolerable social, economic, or political conditions or their combination. Often, there are hurdles that must be overcome. Sometimes, family is the only source of encouragement; other times, family discord worsens these circumstances.

Next, the writer is likely to describe the bewilderment and bedazzlement greeting the newly arrived immigrant in the U.S., first impressions that turn out to be illusions needing to be modulated or overturned. Writers are likely to record several of their most vivid scenes of instruction, tests that they go through with varying degrees of success, often related with a humorous eye at some bumbling misadventure. Frequently, newly arrived immigrants are aided by a guide of sorts—a kind stranger, a predecessor, a teacher, a benefactor, an investor—who appreciates their talent and helps them to find the opportunity they need to make the next step of their journey. Ultimately, these autobiographers manage to make the most of their chances and define themselves within a new cultural identity, although passing that threshold often comes at a price, like an adjustment in their family relations, and entails a diminishing of their previous sense of identity. By the close, they have come to know more about what America will make of them and what they will make of America.

This is the vision of immigration that has proven such an unshakable force in U.S. culture. In these pages, readers will find examples of many individuals whose stories more or less follow this basic scenario from the nineteenth century and that recount privations borne and persecutions withstood. But in ways both superficial and profound, immigration stories at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first differ from their predecessors.

A previous volume, Immigrant Voices, assembled some of those nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century stories of success and their animating trust in hard work and initiative that Americans believe in with all the force of a national creed. Those narratives of becoming Americans remind us that tales of personal striving are often punctuated with a lucky break, an unpredictable circumstance, even a coincidence, or the intervention of an informal support network, like a benevolent aid society such as immigrants from one country might set up for those who follow. Even so, the overwhelming feeling that such narratives convey is the solitude—the often profound loneliness—of the immigrant. And the first difference between contemporary immigrants and their predecessors may be this crucial one. Today’s stories more frequently begin as family tales: families uprooted by war and politics, families denied economic security or legal rights, families needing new opportunities so that they might stay together. Perhaps one family member, the author, has needed to split off and has come as a student or is sent as a sort of emissary to the future. An author’s connections to family and homeland may be troubled, but they remain sustaining, much more so than in earlier generations. Family ties and community connections assert themselves more forcefully now than they were generally represented to do in the past. Immigrant stories, at least in this crucial respect, are evolving.

This book assembles, with just one exception, narratives of immigrants entering the U.S. under the Nationality and Immigration Act of 1965. This was the most important piece of immigrant legislation in the second half of the twentieth century, and it was cosponsored by Emanuel Celler, a long-standing congressman from New York City, himself the grandson of immigrants. Celler’s tenure in the House was so enduring that he actually began his career, forty years earlier, by opposing the notorious Immigration Act of 1924. Stirred by traditional nativist protest, along with the recent surge in distrust that World War I excited, this reactionary law curtailed immigration from eastern and southern Europe by establishing limits based on the 1890 census. The desired result was achieved by creating geographical quotas: the origins of 70 percent of all future immigrants would be limited to three countries—the United Kingdom, Germany, and Ireland. The Johnson-Reed Act, as it was called, continued to exert control throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century and was invoked to deny refuge to Jews fleeing Nazi-occupied countries. Hart-Celler repealed the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, which had essentially sustained Johnson-Reed and which had passed despite President Truman’s veto—he called it “un-American.” The 1965 law struck down these obsolete discriminatory prohibitions, even as it gave new preference to immigrants with special skills. Perhaps even more significantly, it allowed immigration among those who had preexisting family relationships with U.S. citizens and permanent residents. Plus, the 1965 law set aside some 170,000 visas for immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and South and Central America, effectively reversing the percentages from the early part of the twentieth century. It was eventually supplemented by the Refugee Act of 1980, which significantly enhanced immigration for asylum seekers.

So many immigrants since 1965 have turned to the U.S. as a place to practice their talents; so many have come to reunite with their families or to avoid political suppression; and so many have come for their education or to escape poverty. Although many immigrants came from terrible poverty, readers may be surprised by how many enjoyed comfortable, sometimes affluent economic backgrounds. What doesn’t change is the exhilaration of freedom that these immigrants find in their new lives, nor does their pleasure in the expansive power of the American promise. We follow them wherever their careers—in business, in various professions, in service to others—may take them. They generally find some help along the way, but they often have to battle prejudice. Immigrant memoirs tend not to see the resistance these newcomers face as being systemic or debilitating, but rather as challenges to surpass. None of these authors cares to be seen as a victim. Especially is this so for women whose multiple sources of vulnerability—being female, being immigrants, being poor, being people of color—compound the obstructions they must surmount.

The stories that immigrants tell are always negotiating between the world they leave behind and the new life upon which they have embarked. “Life on the hyphen,” as one autobiographer has termed it, describes how hard it is for immigrants to feel wholly a part of either world. This split can be experienced in a person’s heart. Nowhere is that story more vitally encountered than in the tales of generational divide. An older, less malleable generation of immigrants—parents—finds adjusting to contemporary American life too demanding, whereas the children have an easier time making America their own. Often that assimilation is achieved through the grasping of popular culture, like music or slang, even though the child may be torn between full immersion in a new culture and loyalty to parents whose ways represent the values left behind. It’s the classic immigration plot. The Jazz Singer (1927), the very first “talkie,” is about a young Jewish singer who departs from the old-world religious tradition of his father, a cantor. Some of the narratives collected here tell similar stories of what it is like to come as children to the U.S., where they are socialized in school and grow apart from their families, while others record what it is like to start new in a new country without the double bind of opposing allegiances.

That new life is also a story of immigrants finding their niche, their new way of being. Whether they are coming into their own as writers or businesspeople or athletes, these figures make their presence in America felt in various ways. They may do so by cultivating an aptitude they already had or by gaining a skill or expertise they could only attain when given the chance to create themselves anew. Sometimes, the impact that these autobiographers make on the U.S. is modest, their success merely average. Still, the success of immigrants is not merely measured by fortunes or illustrious careers. Rather, we see how indispensable they are to American well-being as people who by reaching their best thus contribute to the sum of the nation’s happiness.

Perhaps the interest of these immigrant lives is merely to suggest that the U.S. is still the place where the everyday level of dreams achieved remains possible for newcomers. When this country first understood itself as a nation of immigrants, it was probably true that there really weren’t too many other places where immigrants were welcomed, where their lives might be improved and where they, in their turn, might benefit those countries. But now, more than two centuries later, more nations see themselves as heterogeneous and make room for immigrants suffering from upheavals and economic distress around the globe. Yet even as these nations are becoming more diverse, America remains the refuge so many millions continue to seek, certainly in its own hemisphere. The burden this creates can sometimes seem unsustainable. Perhaps, in the near future, another new law will enable the country to strengthen its capacity to bolster itself by absorbing new immigrants. If so, as these autobiographies demonstrate again and again, such a law will help to renew the nation’s faith in itself and in its most treasured resource. Once it does, new immigration narratives will then be written, new memoirs recording the rewards and consolations of becoming Americans.

The memoirs selected for this volume are stories we need to know, not just because they help us understand the new challenges facing immigrants, which they do, and not just because they familiarize us with an array of new countries and the reasons immigrants come to the U.S., which they also do. We read these new immigrant autobiographies because the more familiar we are with them, the more we understand this new America, an America made different—better and more fulfilled—as a result of immigration. We read these stories to appreciate the United States we are always in the midst of becoming.

—Gordon Hutner

ANDRÉ ACIMAN

Egypt

André Aciman (1951– ) was born in Alexandria, Egypt, to a wealthy Jewish family of Turkish and Italian descent. His father’s successful textile business supported a luxurious lifestyle of tennis lessons, private tutors, and splendid vacations. As Aciman matured, he became aware of the family’s growing concern about the Egyptian government’s anti-Semitism, which had intensified with the creation of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent border tensions. Even before Israel’s victory in the Six Day War in 1967, Jewish Egyptians faced increasing persecution and expulsion, and the Aciman family moved first to Italy in 1965 and then immigrated to New York in 1968.

Aciman soon enrolled at Lehman College of the City University of New York, where he earned a BA in English and Comparative Literature, followed by an AM and a PhD from Harvard. He has published two sets of essays, False Papers: Essays in Exile and Memory (2001) and Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere (2011), and two novels, Call Me by Your Name (2007) and Eight White Nights (2010). Aciman is currently the Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Published in 1994 to wide acclaim, Out of Egypt won the Whiting Award for emerging writers. Similar to many of the autobiographies in this anthology, Aciman focuses on his extended family and chronicles his own coming of age. The following passage comes from “The Last Seder,” the memoir’s final chapter. Before the nationalizing of their textile factory, Aciman’s father identified fleeing Jewish Egyptians by the smell of their luggage, linking the scent of leather with stigma and shame. Abattoir—slaughterhouse—becomes the word he uses to signal to his son that their own family will soon be leaving Egypt. When his father learns that he’s about to be arrested, fifteen-year-old André is thrust into adulthood and must learn to navigate the necessary web of bribes and encoded messages. Aciman’s father, however, was not the only family member preparing for their escape; unbeknownst to the author, what appeared to be an afternoon of running errands with his grandmother turns out to disguise her routine for smuggling money out of the country, an activity she had been performing for years. The Acimans thus found themselves financially, though perhaps not emotionally, well prepared for leaving their native country.

Excerpt from

Out of Egypt

— 1994 —

“I want you to sit down and be a big boy now,” said my father that night after reading the warrant. “Listen carefully.” I wanted to cry. He noticed, stared at me awhile, and then, holding my hand, said, “Cry.” I felt a tremor race through my lower lip, down my chin. I struggled with it, bit my tongue, then shook my head to signal that I wasn’t going to cry. “It’s not easy, I know. But this is what I want you to do. Since it’s clear they’ll arrest me tomorrow,” he said, “the most important thing is to help your mother sell everything, have everyone pack as much as they can, and purchase tickets for all of us. It’s easier than you think. But in case I am detained, I want you to leave anyway. I’ll follow later. You must pass one message to Uncle Vili and another to Uncle Isaac in Europe.” I said I would remember them. “Yes, but I also want each message encoded, in case you forget. It will take an hour, no more.” He asked me to bring him a book I would want to take to Europe and might read on the ship. There were two: The Idiot and Kitto’s The Greeks. “Bring Kitto,” he said, “and we’ll pretend to underline all the difficult words, so that if customs officials decide to inspect the book, they will think you’ve underlined them for vocabulary reasons.” He pored over the first page of the book and underlined Thracian, luxurious, barbaroi, Scythians, Ecclesiastes. “But I already know what they all mean.” “Doesn’t matter what you know. What’s important is what they think. Ecclesiastes is a good word. Always use the fifth letter of the fifth word you’ve underlined—in this case, e, and discard the rest. It’s a code in the Lydian mode, do you see?” That evening he also taught me to forge his signature. Then, as they did in the movies, we burned the page on which I had practiced it.

By two o’clock in the morning, we had written five sentences. Everybody had gone to bed already. Someone had dimmed the lamp in the hallway and turned off all the lights in the house. Father offered me a cigarette. He drew the curtains that had been shut so that no one outside might see what we were doing and flung open the window. Then, after letting a spring breeze heave through the dining room, he stood by the window, facing the night, his chin propped on the palms of his hands, with his elbows resting on the window ledge. “It’s a small city, but I hate to lose her,” he finally said. “Where else can you see the stars like this?” Then, after a few seconds of silence, “Are you ready for tomorrow?” I nodded. I looked at his face and thought to myself: They might torture him, and I may never see him again. I forced myself to believe it—maybe that would bring him good luck.

“Good night, then.” “Good night,” I said. I asked him if he was going to go to bed as well. “No, not yet. You go. I’ll sit here and think awhile.” He had said the same thing years before, when we visited his father’s tomb and, silently, he had propped his chin on one hand, his elbow resting on the large marble slab. I had been asking him questions about the cemetery, about death, about what the dead did when we were not thinking of them. Patiently, he had answered each one, saying death was like a quiet sleep, but very long, with long, peaceful dreams. When I began to feel restless and asked whether we could go, he answered, “No, not yet. I’ll stand here and think awhile.” Before leaving, we both leaned down and kissed the slab.

* * *

The next morning, I awoke at six. My list of errands was long. First the travel agency, then the consulate, then the telegrams to everyone around the world, then the agent in charge of bribing all the customs people, then a few words with Signor Rosenthal, the jeweler whose brother-in-law lived in Geneva. “Don’t worry if he pretends not to understand you,” my father had said. After that, I was to see our lawyer and await further instructions.

My father had left the house at dawn, I was told. Mother had been put in charge of buying suitcases. My grandmother took a look at me and grumbled something about my clothes, especially those “long blue trousers with copper snaps all over them.” “What snaps?” I asked. “These,” she said, pointing to my blue jeans. I barely had time to gulp down her orange juice before rushing out of the house and hopping on the tram, headed downtown—something I had never done before, as the American School was in the opposite direction. Suddenly, I was a grown-up going to work, and the novelty thrilled me.

Alexandria on that spring weekday morning had its customary dappled sky. Brisk and brackish scents blew in from the coast, and the tumult of trade on the main thoroughfares spilled over into narrow side-lanes where throngs and stands and jostling trinket men cluttered the bazaars under awnings striped yellow and green. Then, as always at a certain moment, just before the sunlight began to pound the flagstones, things quieted down for a while, a cool breeze swept through the streets, and something like a distilled, airy light spread over the city, bright but without glare, light you could stare into.

The wait to renew the passports at the consulate was brief: the man at the counter knew my mother. As for the travel agent, he already seemed apprised of our plans. His question was: “Do you want to go to Naples or to Bari? From Bari you can go to Greece; from Naples to Marseilles.” The image of an abandoned Greek temple overlooking the Aegean popped into my head. “Naples,” I said, “but do not put the date yet.” “I understand,” he said discreetly. I told him that if he called a certain number, funds would be made available to him. In fact, I had the money in my pocket but had been instructed not to use it unless absolutely necessary.

The telegrams took forever. The telegraph building was old, dark, and dirty, a remnant of colonial grandeur fading into a wizened piece of masonry. The clerk at the booth complained that there were too many telegrams going to too many countries on too many continents. He eyed me suspiciously and told me to go away. I insisted. He threatened to hit me. I mustered the courage and told the clerk we were friends of So-and-so, whose name was in the news. Immediately he extended that inimitably unctuous grace that passes for deference in the Middle East.

By half past ten I was indeed proud of myself. One more errand was left, and then Signor Rosenthal. Franco Molkho, the agent in charge of bribing customs officials, was himself a notorious crook who took advantage of everyone precisely by protesting that he was not cunning enough to do so. “I’m always up front about what I do, madame.” He was rude and gruff, and if he saw something in your home that struck his fancy, he would grab and pocket it in front of you. If you took it away from him and placed it back where it belonged—which is what my mother did—then he would steal it later at the customs shed, again before your very eyes. Franco Molkho lived in a kind of disemboweled garage, with a makeshift cot, a tattered sink, and a litter of grimy gear boxes strewn about the floor. He wanted to negotiate. I did not know how to negotiate. I told him my father’s instructions. “You Jews,” he snickered, “it’s impossible to beat you at this game.” I blushed. Once outside, I wanted to spit out the tea he had offered me.

Still, I thought of myself as the rescuer of my entire family. Intricate scenarios raced through my mind, scenarios in which I pounded the desk of the chief of police and threatened all sorts of abominable reprisals unless my father was released instantly. “Instantly! Now! Immediately!” I yelled, slapping my palm on the inspector’s desk. According to Aunt Elsa, the more you treated such people like your servants, the more they behaved accordingly. “And bring me a glass of water, I’m hot.” I was busily scheming all sorts of arcane missions when I heard someone call my name. It was my father.

He was returning from the barber and was ambling at a leisurely pace, headed for his favorite café near the stock exchange building. “Why aren’t you in jail?” I asked, scarcely concealing my disappointment. “Jail!” he exclaimed, as if to say, “Whoever gave you such a silly notion?” “All they wanted was to ask me a few questions. Denunciations, always these false denunciations. Did you do everything I told you?” “All except Signor Rosenthal.” “Very good. Leave the rest to me. By the way, did Molkho agree?” I told him he did. “Wonderful.” Then he remembered. “Do you have the money?” “Yes.” “Come, then. I’ll buy you coffee. You do drink coffee, don’t you? Remember to give it to me under the table.” A young woman passed in front of us and father turned. “See? Those are what I call perfect ankles.”

At the café, my father introduced me to everyone. They were all businessmen, bankers, and industrialists who would meet at around eleven in the morning. All of them had either lost everything they owned or were about to. “He’s even read all of Plutarch’s Lives,” boasted my father. “Wonderful,” said one of them, who, by his accent, was Greek. “Then surely you remember Themistocles.” “Of course he does,” said my father, seeing I was blushing. “Let me explain to you, then, how Themistocles won the battle at Salamis, because that, my dear, they won’t teach you in school.” Monsieur Panos took out a Parker pen and proceeded to draw naval formations on the corner of his newspaper. “And do you know who taught me all this?” he asked, with a self-satisfied glint flickering in his glazed eyes, his hand pawing my hair all the while. “Do you know who? Me,” he said, “I did, all by myself. Because I wanted to be an admiral in the Greek navy. Then I discovered there wa

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...