CHAPTER 1

If I’d died like I was supposed to, l’église de la Madeleine would’ve been the perfect place to mourn me. The church was grand, standing tall in the heart of Paris like a temple where the king of gods doled out punishments, where other greats like Josephine Baker and Camille Saint-Saëns were honored and celebrated by the masses. Above strong Corinthian colonnades on every side were sculptures of judgment, severe and aimed down at its guests. Big bronze doors, though open, didn’t bother at all to feel welcoming. Its statues of saints were poised for war instead of supplication. It would’ve been perfect.

But all of it now had the effect of making me want to shrink away or get out of Dodge. Like perhaps I was a monster to be put down when all I’d ever done was try to survive.

Because I didn’t die like I was supposed to. Coralie did.

People climbed past me while I stood at the bottom of the steps, gazing up at Jesus while his angels glared down at me. It didn’t matter that the icy winter wind nipped at my cheeks and fingertips, or that a few older people cast me glances of recognition from within their bundles of wool. It’d already been more than a month since my face first appeared on the news: one of the missing, then one of the survivors, and according to the very superstitious few, the reason the house fell.

I couldn’t move because I didn’t know if I was allowed to be here. I didn’t want to be here, but I needed to say goodbye.

“We don’t have to go in if you don’t want to,” Keturah said as she pulled her long coat tight around her. Her afro was in full bloom today, voluminous and freshly dyed a radiant shade of lilac, and the coils and kinks fluttered in the breeze.

Andor nodded his agreement and stepped closer, hunching his broad shoulders to try to shield me from the cold and the stares and all that was holding me back. As if he could read my unease as effortlessly as I read his.

He’d carefully framed his handsome face with dark curls in an attempt to cover his milky eye and the scar that ran through it, but it was no use against the wind. And in public, every secret glimpse of me was another pointed at him and all Coralie took from him. Us.

If I were a braver, more considerate girl, I would have seized his hand and taken him away. Spared him the spectacle. Only, we weren’t together together—any potential we could have had seemed to stay behind in Prague, and here we were only distant friends—so instead, I adjusted the lace gloves and turtleneck I used to cover my own scars and pivoted on my heel. “Maybe we just should go—”

“Nope!” Niamh snapped, snatching up my elbow in her small, strong grip. Her hazel eyes glared at me from behind overgrown black bangs. “I don’t know what your problem is, but I’m freezing my tits off. We’re going in—”

Keturah pried the girl’s hand away. “Niamh…”

But I didn’t continue my retreat.

It wasn’t her fault she didn’t know. She wasn’t there when the walls collapsed with me and more than a hundred others still inside. She didn’t know what I did and what was done to me before and after. All she knew was that I needed to be here for some reason, that I’d invited her along, and now I was being unusually spineless. Not at all the girl she met back in Prague.

Niamh studied us, sharp gaze flicking between Keturah, Andor, and me with interest, searching for the secret we held that she didn’t. Then finally she relented, shrugged, and waved goodbye.

“Fine. Do whatever you want, but I am going inside to defrost.”

And so reluctantly I was forced to march up the stairs after her.

It had been only a couple weeks since we’d met and even less since she became one of us. It was my doing that recruited her and brought her into the fold, so I’d be damned to let my only disciple out of my sight so soon, not with Acheron’s power so fresh in her untrained veins and so many vulnerable people she’d be tempted to try it on. No, I’d brave the silly memorial and fundraiser, because I still remembered every craving and dark thought that caught me off guard when I first became an acolyte. And I could never forget the urges that followed long after I knew what I was doing.

To my surprise, Acheron lay dormant as I approached the church. Though I expected it to recoil, to hiss and spit and shirk away from the house of another god, the wicked dark gave neither a lazy glance around nor a passing interest in this place and the growing line of mourners at the entrance. In fact, despite my newfound status as its vessel, despite my harboring some unknown breadth of its eldritch existence in my very body, it shared so little—what it all meant, its plans, its thoughts and relationships to anything. Maybe none of this mattered because Acheron was something so much “other” than I’d ever known. Without any indicators one way or another, I was left to only guess.

By the expressions on Andor’s and Keturah’s faces, I knew their little shards of Acheron weren’t giving off warning signs either.

Shifting from foot to foot as we got in line, Niamh asked, “So, did you, like, know someone who died or something?”

Though she sounded casual, I didn’t miss the prying sideways glance. She wore her scheming plain in her eyes, like she wanted to detect some other answer in my set jaw. Like I was a mark she was preparing to swindle.

My hand flitted to my wallet in my coat pocket, just in case, which she also took note of. No one else noticed.

Inside, the nave of the church was filled to the brim. People crowded the pews, adults and children wiping their eyes and hugging each other while more circled the displays. All around the interior were decorated easels with blown-up pictures of the deceased, framed and showered in flowers and cards and stuffed animals, flammable and dangerously close to the candles. I knew Coralie’s was somewhere among them, but I didn’t want to find it. Near the entrance was a table set up for donations to help the impacted families, and the very sight made the space between my ribs itch.

That day was still crystalline in my dreams, and I remembered all the diamonds and expensive watches twinkling in the light as everyone stood by. The silks and sateen that didn’t shift because no one bothered to help me before it all came down—no one bothered to reach for me, ask after me, when Coralie threw my battered body on display. My blood had pooled on the marble floor, and they only inched away to avoid sullying the ends of their couture gowns.

No one ever contacted me about this fundraiser—would I see any of those donations to soothe the nightmares? The death of my career? Or was I not a good enough victim?

Bitterness burned in me as I raised my chin. I wouldn’t hide from the gazes of recognition, not when I deserved to be here. This was my tragedy too. Though my body was taken away and repaired, part of me had died in Palais Garnier with the rest.

“It’s so sad,” Keturah mumbled, her eyes frozen on a well-dressed couple. They clung to each other before a large easel of a girl my age with a round face, dark hair, and porcelain skin. Olivia Robineau, who glued a razor blade in my shoe.

I swallowed and turned away to study a printed itinerary, thinking that maybe this was a bad idea, after all. Unlike the 113 bodies recovered from the collapse, half of them company members I either studied or trained with, I woke up. Not just alive but more powerful, whether I deserved it or not. Then my attention snagged on the itinerary’s first line, on the name that could only amplify my dread.

“Rose-Marie, thank you for coming.”

Behind us, an event organizer held a tall, model-esque woman with familiar golden hair and rosy cheeks. She wore a long, tailored coat of royal blue, which I knew was her favorite color after platinum and silver—like the brooch pinned to her lapel to catch on the candlelight all around her—and her posture and gentle expression could only be found on a seasoned ballerina. Achieved through years of conditioning, on and off the stage.

Rose-Marie Baumé, Coralie’s famous, star-powered mother, stood in the entrance of the church, looking exactly as I remembered her: harsh and regal. Even in grief, she was cold and unmoved, and even in grief, Coralie’s father was absent from her side. Looking at her, you wouldn’t even know she’d lost someone. That the “natural disaster” the authorities determined had leveled the building was, in fact, her daughter.

Though it occurred to me that she could come, I didn’t think she would. I didn’t realize I’d have to brace myself in case she noticed me.

For six years, I’d lived as Rose-Marie’s unofficial ward, her daughter’s best friend and living shadow who followed her everywhere. Every insult, every twitch in her mouth when I’d surpassed and danced circles around Coralie, I’d memorized. I’d also watched as Rose-Marie ran for her life, leaving her daughter to self-destruct. With me still in her clutches.

For all my guilt about killing Coralie, even if I had to, Rose-Marie had created the monster she became.

“Just great,” I muttered.

Rose-Marie parted from the event organizer and quickly came to a halt when those emerald-colored eyes found mine. It only lasted for a breath, but it felt like we’d held each other’s gazes for so long that anyone might have picked up on it. Picked up on how my shoulders climbed to my ears, like some small dog raising its hackles, how she frowned almost imperceptibly before she kept walking.

She marched past, so close I even smelled her freaking Dior perfume. No acknowledgment. No apology. No well wishes. All I was worth to her was a minuscule frown. Years of knowing each other reduced like I was a speck of dirt on her precious coat. A nuisance, and not the girl her daughter had chosen to torment in her final moments.

As always, despite everything, my thoughts went quiet in the wake of Rose-Marie’s condescension. It was so easy to lash out and throw someone down the stairs or rupture muscle, but her? The only way to survive in her orbit was to make myself small, and I just did it all over again like a reflex.

“Bitch,” Keturah cursed after her, loud enough for her to hear. She placed a protective hand on my shoulder.

But Rose-Marie carried on, the famous church transformed into a catwalk, her expensive stilettos clicking loudly on the old, stone floors.

Power flooded my veins in the flip of a switch. Acheron was awake and paying attention to my panic now, attuned sharply to the rhythm coming from Rose-Marie’s direction. From her steady, unflinching heartbeat.

We could correct this situation, if you want, it said, curling around my spine, voice rolling through my bones like thunder.

And it was right—I did want.

But I took a slow, centering breath to quell the temptation instead. It was so easy to be a monster now, with so much power at my disposal and so much spite to keep me going. It would take nothing at all to unfurl my darkness and make Rose-Marie small for once in her wretched life.

You should snip the tendons behind both knees and make her crawl to you like the worm she is. We could make her beg for mercy and kiss your feet in worship, and then—

“Shut up,” I snapped through gritted teeth, to the thing no one could see or hear but I could feel now slinking away. That only earned me even more glances, the girl talking to her shadow. Just what I needed.

Even Niamh noticed and resumed her appraisal of me. She didn’t know that Acheron and I talked, and I wasn’t sure how much I wanted to share when I was still trying to understand myself what it meant to have an eldritch god riding around in your skin.

As casually as I could muster, I dropped my shoulders and found a comfortable place to stand in the back of the pews. “Forget it. It’s whatever.”

The memorial talks would begin soon, and that mattered more than some imaginary war with Rose-Marie. A dark-wood podium had been decorated with flowers at the head of the church, and Rose-Marie rose to it, in rapt discussion with another organizer. She was to lead the introductions, according to the itinerary, and give her heavy endorsement to the event. If there was ever someone the public trusted, it was her. Still, Acheron was right to call her a worm.

“You don’t like her?” asked Niamh with a glint in her eyes as she went back to watching Rose-Marie. “I don’t get why, if you can do something about her, you don’t.”

There was no easy way to explain the futility of it, fighting these kinds of people in these ways—Rose-Marie and her ilk would never see me as an equal, even if I held her at eye level by her throat. And besides, she was a vestige from an old life. She didn’t matter anymore.

“She has every right to hate me,” I explained instead as stonily as I could, keeping my gaze ahead and locked onto Rose-Marie as she took the podium. “I’m the reason her daughter’s dead.”

I didn’t want to see Niamh’s expression, to catch it change into distrust or, worse, even more intrigue. Though I’d survived, though I’d stopped a situation from becoming worse, I couldn’t say without a doubt that I’d done something good.

Rose-Marie tapped the microphone, cleared her throat, and smiled. It was the same bland expression on all her Bulgari and Dior ads, a look I’d seen on TV and in person for years. Nausea rolled through me as I thought of how once I’d wanted to be like her, even as I despised her.

“I hope you can hear me well,” she started, eliciting chuckles from her enamored crowd. If we couldn’t, no one would ever interrupt to say, anyway. “I come to you today, not just as a member of the board at Opéra Garnier, but also as a mother. A grieving mother.”

Here, a profound silence descended over the church. Faces of my classmates and colleagues frozen in time surrounded and watched us, while Rose-Marie Baumé stood in the holy rays of light like some walking parable, and they all ate it up. None of them knew that she was a coward. She didn’t try to save her daughter before the collapse, and she certainly wasn’t screaming her name in the rubble after. I’m not sure they would care either.

Rose-Marie gestured to one of the largest portraits, positioned conveniently right next to the altar, and it was like staring at a younger version of her. The same eyes, the same coloring, the same nose, the same posed and airbrushed face. My Coralie was different: Her hair was wild and frizzy, cheeks freckled, grin defiant, attitude petulant. Nothing like the sweet, poised doll on the poster.

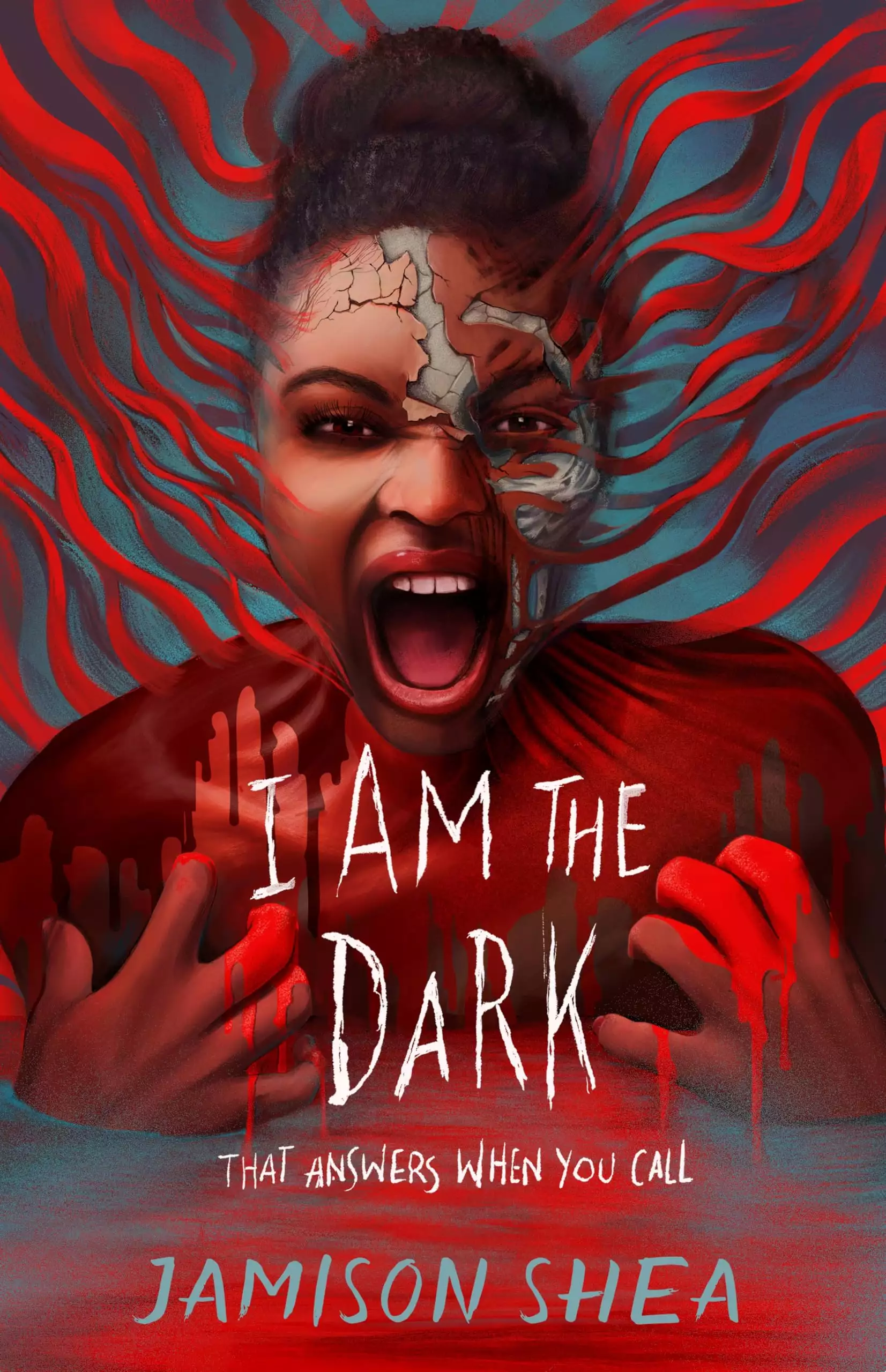

Copyright © 2024 by Jamison Shea

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved