- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

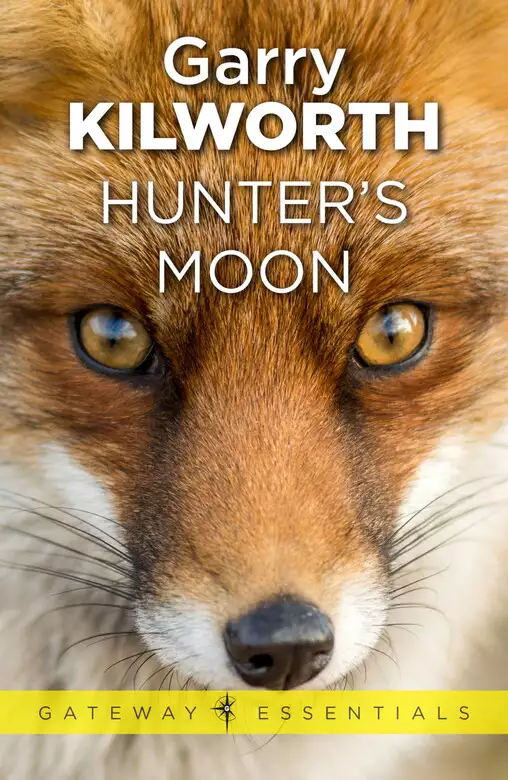

A story of foxes, from O-ha and her six unborn cubs in Trinity Wood to Camio, an American Red Fox far away in his zoo cage. The animals in Trinity Wood feel safe from predators, but their world is changing, humans are coming closer with their bulldozers, houses, their guns and their dogs.

Release date: February 18, 2013

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 328

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hunter's Moon

Garry Kilworth

O-ha had found an old earth in the clay bank just inside the tree line. She had freshened it a little by scraping out the tunnel and chamber, but like most foxes was not fussy about the state of her home. The main priorities were that it remained warm and dry. It was simply a place of safety where a fox could sleep, hopefully without disturbance. Although she liked simple clean lines and might admire the earth for this reason, she was an untidy creature and any house-cleaning consisted of tossing rubbish just outside the entrance. Even that chore was done with an impatient sigh, as if she were wasting her time with trivial, unimportant matters while the world awaited great things from her. She was not unusual in these traits. Though personal cleanliness is important to foxes, the idea that one should spend time keeping the home tidy was dismissed with contempt.

The entrance to the earth was almond shaped and around its roof arch was the strong protective root of a benign-looking oak tree. The oak had one of those sturdy squat trunks which brought its lowest branches close to the ground. On days when even the slightest breeze was blowing, the movement of the shadows from these boughs produced a camouflage effect which helped to disguise the earth’s entrance. This, coupled with the way the exposed root twisted over and round the hole, giving it an overhang, meant that any unknowing observer would have to be at eye level with the opening to realise that there was a hole there at all. The tangle of roots breaking the surface all around the matronly oak served even further to confuse any enemy out searching for the homes of foxes.

To the other side of the earth’s entrance, beyond the star mosses which formed a padded area running eastwards, was an alder which dripped bright berries in the autumn. The cool forbidding shade of the oak kept this lesser tree, with its arthritic limbs, from encroaching on a space where it was unwelcome. Nailed to its trunk however, were the remnants of a barbed wire fence, which O-ha found to be a very effective back scratcher in the warm weather, when her fleas became too active.

Since O-ha was an intelligent-looking vixen, with a glossy coat which varied between rust-red and grey, depending on the light, she was courted by at least three dog foxes. She chose a male her own age, a fox with humour in his eyes and a way of cocking his head to one side that turned her legs to willow wands.

‘I admire you above all other vixens,’ A-ran told her. ‘You’re bright, alert and … oh, dozens of other things. It would take too long to tell you all the reasons why you make me dizzy with excitement every time I see you.’

When she gave him her decision, they were knee-deep in autumn leaves, and he showered her with them in his joy. The sky was alive that day, with rushing clouds which swept shadows across the land and produced an ethereal half-light full of ever-changing shades. They went out, on to the windblown grasslands, under this strange sky. There, they seemed isolated. His eyes danced with wild unusual pigments, reflecting the strange radiance which surrounded them.

She gave herself a dozen practical reasons why he was the best mate for her, dismissing his claim that she was a romantic. In the warm damp grass, they tumbled and nipped each other, finding excitement in touching even though it was not a time for serious mating. They learned the intimate details of each other’s bodies, the scratchscars on O-ha’s nose, the small ‘v’ that had been clipped from A-ran’s right ear, both the result of hunting play with siblings. She thought the small white patch on his flank unusually attractive, and he remarked on the sleekness of her muzzle-hair. They found other things upon which to comment, almost always favourably.

A-ran changed his name to A-ho to reflect her family name as was traditional among foxes. It was a heady time for both of them. They were young enough for most ordinary experiences to be great new discoveries. Their parents, they told each other, were all right in their way, but somehow lacked the clear thinking and reasoned judgement which they themselves possessed.

‘I suppose they were quite well thought of in their day,’ said A-ho, generously, ‘but that was ages ago. The world’s quite a different place from what it was half a dozen seasons ago. The hunting issue for example …’

And O-ha would lie beside him in their earth, adding her observed opinions as if they were the only ones which an intelligent fox could possibly contemplate. Occasionally, in the darkness, she would lick his nose, or he would rest his head against her slim shoulder. They were entirely comfortable in each other’s company, to the exclusion of the rest of the world.

‘Do you love the smell of pine needles?’ she might say.

‘Pine needles? Wonderful aroma. I’d go out of my way to get a good whiff of pine needles – and sap.’

‘Oh yes, the sap too …’

And they would both marvel at their compatibility, how they both liked the same things, disliked the same things, how startlingly lucky it was that they had each found someone who liked the scent of pine needles, ‘… especially in springtime.’

‘Undoubtedly the most effective time for sniffing pines.’

Were there ever two foxes more suited to each other in the whole history of the world? Was there ever a pair whose opinions on life matched each other’s so sharply, so precisely? Was there ever a more intelligent vixen, or wise dog fox, given that they were still quite young and willing to learn? Never, they agreed.

‘Of course,’ said A-ho, ‘these observations are for our ears only.’

That autumn was a magical time for the two new mates. There were golden scents to the air and hunting was good. They lived almost constantly in each other’s company, though when the colder weather came and Ransheen cut through the grasses, it was necessary for them to go out alone sometimes.

It was mid-winter and the air was still, clean and sharp.

A-ho had been keeping close to her side for many days and his rising excitement was indicated by the way he carried his tail: high, like a bushy pennant. O-ha was keenly aware of her mate and was sometimes irritated by him as he persistently brushed against her, leaving her hardly enough room in the earth to move a paw. His bright eyes never left her and though he might be the handsomest dog fox in the known world, she felt she could not draw a breath, but A-ho was there to watch and assist her. She felt the atmosphere was claustrophobic and tense. She too was aware of a stirring of excitement in her body, but there were limits to her patience, and once, he had even tried to mount her before she was anywhere near ready for him and she had to snap at his flank, making him back away in disappointment.

However, today her body felt warm and sweet, and she was aware that she was putting out a fragrance which had turned the brightness in his eyes to a hot fire. She waited as he shadowed her every move, his body language full of curves, soft displays.

Suddenly, she rose to her feet and went to the exit to the earth, licked her nose, went through the rituals to test the wind for danger, then slipped outside. As always there were a thousand scents vying for her attention, which her brain filtered automatically, so that the important ones received priority. A thousand scents, most of which were too subtle or too weak for a man to detect.

Although it was cold the sun shone down with winter hardness through the trees of Trinity Wood. She found a patch of grass and stood there, letting the weak rays warm her fur. A-ho was right behind her.

After a few moments he came up beside her and touched her flank with his forepaw. She could feel him trembling and an electric shiver went through her body. A-ho nuzzled her, under her chin. She could feel his hot breath on her throat and his tongue wiped a swathe through her soft fur. She made a sound in the back of her mouth.

He was rubbing against her now, licking and nuzzling, running his paws over her back. She liked it. She closed her eyes and enjoyed the rippling sensation that travelled through her limbs and torso. That was nice. He was nice. Opening her eyes again, she looked at him. He was strong, proud and magnificent. His fur was fluffed and clean, his dark ears erect. His firm jaw was the most handsome thing about him. No other vixen had a dog fox like her’s, such a wonderful mate. She nipped him sharply, to demonstrate her affection. How lucky she was to be the centre of attention. It was obvious to her that the whole world might collapse at that moment, and A-ho would not notice. He could see only her and he blazed like a high, hot fire on the grass, warming her with the red flames of his coat, ready to burn deep inside her body.

Suddenly, he was behind her, and the skies turned crimson and the grass began to crackle beneath her. She let out a short yelp: he crooned, once, and after a few seconds it was over, but it felt good and sweet and there was a taste in her mouth like windfalls coated with honey, which lingered for some time afterwards.

After a while, the world righted itself and she was able to look at her mate again. She studied his long, pointed muzzle, the black-tipped ears, the russet coat. He seemed happy. He lay on the damp grass, his narrow, foxy eyes drinking in her form, and his tongue lolling out.

‘Put your tongue in,’ she said.

‘Why?’

‘Because …’ She looked around, wondering if they had been observed. Not that she was worried about others witnessing a very natural act – they would not be interested anyway – but her curiosity was back, now that it was over.

A-ho let out a triple bark, and then a loud scream, before giving her his cocked-head look which he knew always endeared him to her.

‘All right, tell the world,’ she said. ‘If you feel it’s necessary. Personally, I don’t. They can all see what a tremendously virile fellow you are.’

‘It’s traditional,’ he remarked, casually.

‘Is it,’ she said, flatly. ‘I wonder who started that tradition? Some poor dog fox who had only just learned to play “wind in the trees” with his new mate, I suppose?’

She was teasing him.

Over the next three days they made love on several occasions and each time it was as good as the last: not better, but certainly as good. The sky changed colour many times. The air seemed to have promises hanging in it like lanterns of fruit which had hung in the autumn trees, filling the world with heady scents.

Yet Melloon had long since departed, leaving bare damp trees, dark with fungi, and bushes without berries to blood their branches. Sodden leaves covered the floor of Trinity Wood and there was great competition for meat amongst the predators: the owls, the hawks, the weasels. O-ha’s diet consisted of three-quarters meat. She had to be sharp. There were birds about, in the winter, and on days when the ground was soft there were earthworms to be had. Or she would steal winter cabbage from the havnot, the farmlands around Trinity Wood. Shortly after the mating season was over, she found a fence full of gubbins, the fox word for animals killed and left by humans. These were old crows and stoats hung on fence wire. She cached some around the area, marked the place, then took one home to A-ho. He thanked her by licking her ear. Now that the mating was over, there was no strain in the relationship. They could touch and be touched without any thick syrupy feelings interfering with their affection for one another.

Inside her, there were changes taking place, which were pleasant. She looked forward to warmer weather and Switter, the spring breezes. Many of the meadows around Trinity Wood were still old grasslands, and birds such as the partridge were still able to find the sawfly larvae and leather-jackets which fed only on certain plants and without which they could not survive. There were still hedgerows and ditches, necessary to birds, mammals and reptiles. The hedgeless landscape and sterilised new grasslands were moving in but had not yet overtaken the area around Trinity Wood.

The wood itself was an old-world mixture of coniferous and deciduous trees – yew, cedar, juniper, oak, beech, alder – and not one of the man-made silent forests of sitka spruce, where pine needles suffocate any undergrowth and the insects necessary to animal life discouraged from moving in. Silent, utterly, unerringly, silent. In the new pine forests the shadow was heavy and forbidding, the neat rows of trees so close together that a rabbit could not squeeze between them. In Trinity Wood, the shade was light, and the arrangement of the various trees, satisfyingly untidy.

Of course, O-ha and the other animals of Trinity Wood took all this for granted, even though itinerant beasts brought warnings of an outside world that was being reshaped to suit the comfort and needs of those ugly bipeds whose hairless, featherless bodies were draped with loose-fitting cloth, and who showed their teeth even when they were not angry.

Not in our time, they said to themselves and to each other. The woodlands and fields will not change in my lifetime.

True, said the widgeon, whistling on the wind.

And in a voice like two pebbles being struck together, the stonechat agreed.

The shrew, the grasshopper, the bark beetle, the fox, the squirrel, the gregarious rooks and solitary crows, the shellducks that nest in old rabbit holes along the ditches, the adder, the smooth snake, the magpies who form ad hoc, mysterious parliaments in open fields, to conspire and discuss revolution, the winter balls of ants in hollow logs, the tree-creeper, the nightjar, the hare and the rabbit, the badgers, the robin that sings for eleven months of the year and falls to silence in August, the rafts of coots on the river …

… they all sang the same song,

Not in our time.

So O-ha and the other creatures of Trinity Wood and the surrounding countryside did not concern themselves with the warnings brought in by outsiders. They confined their interests to the subtleties and vagaries of the winds which carried the scents and sounds necessary to everyday living, to the changing seasons, to avoiding contact with humans. The wood mouse, surrounded by predators, had enough to worry about without thinking of future catastrophes that might never come to pass. The swifts and swallows were too busy gathering insects over stagnant pools. The moorhens stuck their heads under leaves when such dreadful thoughts entered their minds, believing they were totally hidden from the world, but soon forgot why they were doing it and went out into the pond to feed again.

Life was already quite fraught enough without having to heed something about which they could do nothing. O-ha’s main anxieties concerned getting enough food for herself and her unborn cubs and evading the hunt.

One night she rose from her bed leaving A-ho fast asleep and staggered outside. She felt sleepy and failed to observe the rituals of leaving-the-earth: something she was never normally careless about.

Above the wood was a hunter’s moon, casting a light over the scene that filled the world with shadows. The shadows moved and danced as if they were alive.

O-ha set off across the hav, feeling quite strange. It was as if she were not herself but some other vixen moving across the moonlit landscape of the slope below Trinity Wood. All around her were the sounds of other creatures in the grasses, going about their nightly businesses. Then, suddenly, all went still. There was the smell of danger in the air.

The moaning note of a huntsman’s horn floated over the fields.

O-ha’s heart picked up the sound before her brain and she was already moving rapidly through the thickets of blackthorn before she was conscious of what she had to do. Her feet kept getting tangled in the network of shadows though, hindering her progress. She wished there was no moon, no hunter’s moon, for the human beasts to see by. Yet, they had their hounds and horses to see for them, to smell her out and run her down.

The human barks grew louder and she could hear the thudding of horses’ hoofs on the turf. The hounds were screaming at each other, urging each other on. Shadows grew like brambles around her, catching in her coat, holding her back. It was as if the black shadows of the briars had sided with man and were acting like snares and traps to slow her down, cage her, until the hounds caught up with her.

She ran until her heart was bursting. On the top of a ridge, in the full light of the hunter’s moon, the hounds caught her and fell on her. She screamed for mercy as canine teeth crunched her leg bones and tore the joints apart. The pain was incredible as pieces of flesh were ripped from her live twisting body and her blood splattered the faces of her killers.

The eyes of the hounds were bright with bloodlust, and they changed as their jaws broke her bones, stripped her coat from her flesh. They changed into white human faces, the lips curled back and that ugly barking which only humans made, coming from their throats … ‘HA-HA-HA-HA-HA-HA …’ relentlessly. Dogs with human heads, and coats and caps, insane with the pleasure of tearing a living creature to pieces. Human heads with dogs’ bodies, ugly with the excitement of death and its younger brother, pain. All the while she cried for mercy, for herself and her unborn cubs, but there was none to listen. All ears were deaf, except to the sounds of the kill.

Then, strangely, she was outside her body, and looking on. And she saw that it was not herself in the centre of those frenzied human hounds, but A-ho, her mate. She screamed at them to stop, to leave him alone. She could see his body contorting in agony and his eyes pleading for her help. Yet she could do nothing but watch him being torn to death.

And when he was dead, one of the riders lifted him up, one of the riders with a human body and dog’s head lifted him up and bit off his tail, wiping the bloody end over his face. ‘HA-HA-HA-HA-HA!’

Then, as he dangled there, from the human hand, a wasted empty skin with no tail, the head flopping this way and that, she could see it was not A-ho, it was not herself, if was just another fox, only another fox, anonymous, unknown. It was another fox, not just another fox, it was the fox, it was all foxes. It was her, it was A-ho, it was her grown cubs. It was her mother, her father, her kin and kind.

She woke up in her earth, A-ho beside her, saying, ‘What’s the matter? Are you having the nightmare?’ and she realised she was whining in her sleep. Her noise, her twitching body, had woken him.

She nuzzled into him.

‘Yes, it was the nightmare.’

It was the bad dream of all foxes, the chase over the landscapes of the mind, and the gory end that was never an end because it would come again, and again …

The winds are gods. Without them, survival would become a nightmare. They carry the scents and sounds necessary to fox awareness of all things: danger, food, rain, love, trees, earth, landscape – all things. Each individual wind is a deity with a secret name, to be whispered by the rocks and trees, to be written on the surface of the rivers and lakes. More important than the sun or the moon, the wind is the breath of life. Somewhere, seasons out of time, is a mythical land known as Heff, where a shapeless form breathes through a series of hollow tree trunks full of holes of different sizes. This is the palace of the winds.

The time was Ransheen, the white wind, when darkness grew like horns, deeply into the ends of the day. Soft things had become brittle and the landscape had taken on sharp edges. Ransheen brought with her a belly full of flints and lungs that burned.

It was night and O-ha prepared for the ritual of leaving-the-earth with unhurried precision: an elaborate procedure which tested for dangers outside and ensured the secrecy of the earth’s location.

She licked her nose and poked it out into the cold path of Ransheen, getting Her strength and direction. A thousand scents were out there, each one instantly recognisable. The smells of men and dogs were absent, however, and after some time O-ha was satisfied that it was safe and gradually emerged from the earth, to stand outside.

The world was a block of stone with a frozen heart. After the mating, the real winter had set in, almost as if their coming together had been a signal for the ice to advance. Around O-ha the trees of Trinity Wood were sighing in the moonlight. She moved her head from side to side, slowly, testing the odours that Ransheen carried in Her unseen hands, the sounds that She bore.

Then the swift dash to put ground between herself and the earth, through the edge of the thicket and out into the hav, the open heathland.

There was a stalking moon, throwing its pale light over the landscape. When she was a cub O-ha’s mother had told her that the moon was the detached soul of the sun. In the beginning, not long after the world was formed, there had been no night or day: world-shapers like the great fox A-O, and the wolf Sen-Sen, moved through the Firstdark using scent and sound, and had no need of light. This was at the time before humans came out of the sea-of-chaos. However, the giant Groff, sent by humans to prepare the world for their invasion, had been instructed to provide light for the humans to hunt by. He plunged his hand deep into the earth and came up with a ball of fire. He called this molten ball the sun, but when he tossed it up into the sky, he threw the sun so hard its soul became detached from its body. This ghost of the sun was called the moon, and followed a similar but separate path in its circuit of the world.

The wolf and fox knew that the reason Groff was providing the bright light of day was so that men could more easily find and kill them, and they tried to destroy the giant. But Groff could not be hurt, since he was made of nothing but belief, and the only way he could be destroyed was for men to doubt their faith in his existence.

O-ha used the ancestral highway from Trinity Wood to Packhorse Field. Other fox and badger byways criss-crossed this main artery but she ignored these, for none of them led to water, her present objective.

Her tread was delicate, and from time to time she paused to look over her shoulder, not to see, but to listen, for like all her kind she was unable to focus on a stationary object for more than a few seconds. She passed by a cottage, using the ditch at the end of its long garden as cover. She could smell the iron fence posts, and the steel wires that ran between them. Her ears picked up the sound of the clock, ticking in the bedroom of the house. Somewhere, out on the road that ran by the cottage – perhaps half a mile distant, a man was walking. His scent came to her on the back of Ransheen.

She lay in the dank ditch, watching the cottage for a while, her body tuned to the night. All remained still. It was wise just to wait sometimes, if for no other reason than some faint, distant sound had disturbed her mental attitude. Or perhaps nothing at all that could be seen, smelled or heard? Perhaps just a feeling? Survival did not depend upon knowing everything but on following instinct. If the feeling said ‘stay’ then she stayed. Her thirst could wait. Unlike humans, O-ha did not invent reasons for continuing normal activity. There were no chores which could not wait. She was quite willing to do nothing, be nothing, for as long as her mental state remained unsettled.

Eventually she resumed her journey to the pond.

O-ha was a very conventional fox, and even as she walked she carried out certain rituals. There was one set of these which were rarely referred to or spoken of in any society, even between pairs, though it was carried out religiously on all occasions: the marking. Almost subconsciously, O-ha marked certain areas of the highway with her urine, so that if A-ho came by that way he would know she had recently been there.

As she walked along the ancestral highway O-ha felt the frosted grasses brushing her legs and she thought wistfully of Melloon, the Autumn wind, and of the fruits and mushrooms that had since gone.

At one of the fox byways she heard a familiar tread, as delicate as her own, and smelled an odour which always sent a shiver of delight down her spine. She waited, poised, and soon another red fox came out of the tall white grasses.

‘A-ho,’ she said. ‘I didn’t hear you leave the earth. Why didn’t you wake me?’

A-ho stopped and scratched his muscled body with the fluidity of a cat.

‘You were sleeping too soundly. Seemed a shame to disturb you.’ He flicked his head. ‘Been down to the orchard, looking for rats, but all the windfalls have gone. Nothing to get them from their holes. What about you?’

‘Just going down to the pond.’

‘Well, you be careful – in your condition …’

She was three weeks pregnant now and a warm glow was in her belly.

‘I’ll be all right.’

‘Be careful,’ repeated A-ho, and then he was gone, his dark coat moving along the ancestral path, towards their earth.

O-ha continued her trek through the moonlight. In the distance a tawny owl hooted, Ransheen carrying the sound over the fields.

The man she had smelled earlier, out on the road, had now cut across the fields and was walking towards the animal highway. She could hear the crunch of his boots on the hard ground. The lumps of frozen soil were hampering his progress. Occasionally he lost his footing and barked softly.

O-ha slipped into the grasses and lay still, waiting for the man to pass. His direction crossed her path and among all the other scents which he carried around him in a cloud was that of a shotgun. While there was darkness to protect her, and the fact that the man appeared to be ill in the way that men she encountered in the early hours were often sick, she did not wish him to fire the weapon. There were noises and smells associated with guns that were reminiscent of storms, of thunder and lightning and trees blasted into black charred stumps. It was always difficult to think, to keep a clear head, under such circumstances. It did not matter that one survived without being hit: these were enough to turn a fox’s head and make it do something stupid.

The man came within a few feet of her, smelling strongly of smoke. His tread was unsteady, with much stumbling, and once he fell over and lay still for a few moments. His shotgun clattered against a stone and O-ha held her breath, expecting it to belch flame, to tear a ragged hole in the night’s stillness. Nothing happened, no fire, no noise.

The man gulped at the frozen air, his breath snorting through his nostrils. He growled softly and heaved himself to his feet. Then he swayed forward, as if searching the ground. O-ha heard him pick up the shotgun before barking harshly at the moon. His head began weaving about as he regained his stance. He slapped at his clothes, yapped again, then continued his meandering over the fields.

O-ha’s encounters with humans were not infrequent, though it was rare for them to be aware of the meeting. Humans had the sharp eyes of a predator which could not rely on smelling the prey, but they had lost the instinct which went with such vision. Many times she had held her breath, thinking that a human was aware of her, only to have the intruder pass by. She had decided that most humans were preoccupied creatures, whose anxious minds were on things which were outside the considerations of a fox. Why else would solitary men wear such strange expressions, walk around with eyes fixed on some point far beyond their range of vision, smell constantly of one kind of fear or another? And when there was more than one of them, they were usually so busy barking at each other that the world could turn upside down and they would not notice. As for killing, humans sometimes killed not for territorial reasons, nor for food, but for reasons which foxes had never been able to understand. There were times when humans made a great spectacle of killing foxes, and there were times when they did it slyly, secretly, while no one was watching.

O-ha was no stranger to death, even to slaughter. She and A-ho had once entered a chicken coop and slaughtered the whole population. For several minutes she had been able to see nothing but a hazy red cloud before her eyes, and her heart moved to her head, pounding there. Her coat overheated and she just snapped at anything that moved. This was not a blood lust. This was good husbandry. Afterwards the pair of them had carried away and cached as many chickens as they were able, before the farmer arrived on the scene.

O-ha understood about killing, even in numbers, so she did not think humans unnatural, only unreachable.

O-ha came to the pond and found there was a sheet of ice covering its surface. It shone frostily at her

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...