1Now:The Producer

Our little movie that couldn’t had a crew size that has become fluid in the retelling, magically growing in the years since Valentina uploaded the screenplay and three photo stills to various online message boards and three brief scenes to YouTube in 2008. Now that I live in Los Angeles (temporarily; please, I’m not a real monster) I can’t tell you how many people tell me they know someone or are friends of a friend of a friend who was on-set. Our set.

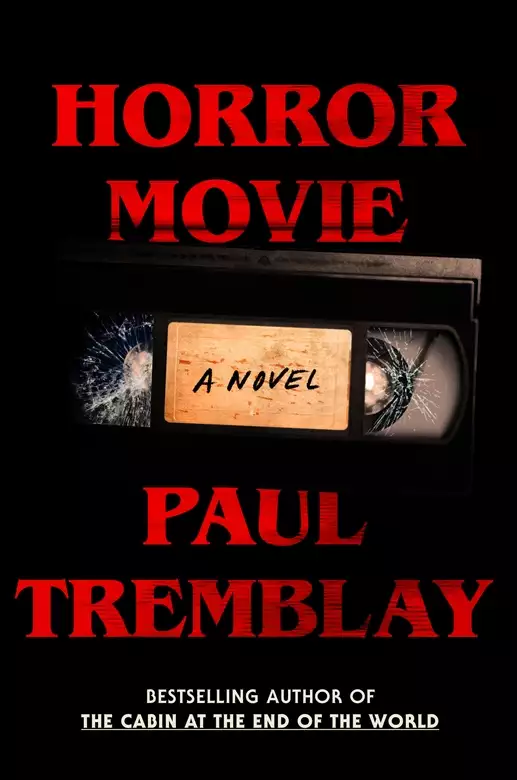

Like now. I’m having coffee with one of the producers of the Horror Movie remake. Or is it a reboot? I’m not sure of the correct term for what it is they will be doing. Is it a remake if the original film, shot more than thirty years ago, was never screened? “Reboot” is probably the proper term but not with how it’s applied around Hollywood.

Producer Guy’s name is George. Maybe. I’m pretending to forget his name in retribution for our first meeting six months ago, which was over Zoom. While I was holed up in my small, stuffy apartment, he was outdoors, traipsing around a green space. He apologized for the sunglasses and his bouncing, sun-dappled phone image in that I-can-do-whatever-I-want way and explained he just had to get outside, get his steps in, because he’d been stuck in his office all morning and he would be there all afternoon. Translation: I deign to speak to you, however you’re not important enough to interrupt a planned walk. A total power play. I was tempted to hang up on him or pretend my computer screen froze, but I didn’t. Yeah, I’m talking tougher than I am. I couldn’t afford (in all applications of that word) to throw away any chance, as slim as it might be, to get the movie made. Within the winding course of our one-way discussion in which I was nothing but flotsam in the current of his river, he said he’d been looking for horror projects, as “horror is hot,” but because everything happening in the real world was so grim, he and the studios wanted horror that was “uplifting and upbeat.” His own raging waters were too loud for him to hear my derisive snort-laugh or see my eye-roll. I didn’t think anything would ever come from that chat.

In the past five years I’ve had countless calls with studio executives and sycophantic producers who claimed to be serious about rebooting Horror Movie and wanting me on board in a variety of non-decision-making, low-pay capacities, which equated to their hoping I wouldn’t shit on them or their overtures publicly, as I and my character inexplicably have a small but vociferous, or voracious, fan base. After being subjected to their performative enthusiasm, elevator pitches (Same movie but a horror-comedy! Same movie but with twentysomethings living in L.A. or San Francisco or Atlanta! Same movie but with an alien! Same movie but with time travel! Same movie but with hope!), and promises to work together, I’d never hear from them again.

But I did hear back from this producer guy. I asked my friend Sarah, an impossibly smart (unlike me) East Coast transplant (like me) screenwriter, what she knew about him and his company. She said he had shit taste, but he got movies made. Two for two.

Today, Producer-Guy George and I are in Culver City comparing the size of our grandes while sitting at an outdoor metal wicker table, the table wobbly because of an uneven leg, which I anchor in place with the toe of one sneakered foot. Now that we’re in person, face-to-face, we are on more equal ground, if there is such a thing as equality. He’s tan, wide-chested, wearing aviator sunglasses, a polo shirt, and comfortable shoes, and

younger than I am by more than a decade. I’m dressed in my usual uniform; faded black jeans, a white T-shirt, and a world weariness that is both affect and age-earned.

He talks about the movie in character arcs and other empty buzzword story terms he gleaned from online listicles. Then we discuss what my role might be offscreen, my upcoming meeting with the director, and other stuff that could’ve been handled in email or a phone/Zoom call, but I had insisted on the in-person. Not sure why beyond the free coffee and to have something to do while I wait for preproduction to start. Maybe I wanted to show George my teeth.

As we’re about to part ways, he says, “Hey, get this, I randomly found out that a friend of my cousin—a close cousin; we’d spent two weeks of every summer on Lake Winnipesaukee together from ages eight to eighteen—anyway, this friend of hers worked on Horror Movie with you. Isn’t that wild?”

The absurd part is that I’m supposed to go along with his (and everyone else’s) faked connection to and remembrance of a movie that has become fabled, become not real, when it was at one time decidedly, quantitatively real, and then the kicker is there’s the social expectation that I will acknowledge our new shared bond. I get it. It’s all make-believe, the business of make-believe, and it bleeds into the unreality of the entertainment ecosystem. Maybe it should be that way. Who am I to say otherwise? But I refuse to play along. That’s my power play.

I ask, “Oh yeah, what’s their name?”

I insist people cough up the name of whoever was supposedly on-set with me thirty years ago. I respect the person who at least gives one, putting their cards on the table so I can call their bluff. Unerringly, Industry Person X (now, there’s a real monster; watch out, it’s Industry Person X, yargh blorgh!!!) gets rattled and is affronted that I dare ask for a name they cannot produce.

The umbrella over our heads offers faulty, imperfect shade. Producer-Guy George’s tan is suddenly less tan. He asks, “My cousin’s name?”

“No.” I’m patient. After all, with my ceremonial associate-producer title, he and I are going to be coworkers. “The name of your cousin’s friend. The one who was on-set with me.”

“Oh, ha, right. You know, she didn’t tell me, and I forgot to ask.” He waves his hands in the air, a forget-I-said-anything gesture. “Her friend was probably a grip or an extra and you wouldn’t remember.”

I lean across the tabletop, lifting my foot away from the leg’s clawed foot. The table quakes. George’s empty coffee cup jumps, then falls onto its side, and circles an imaginary drain, leaking drops of tepid brown liquid. He fumbles for the cup comically, but he’s too ham-fisted for real comedy, which must always include pathos

He rights the cup, then leans in, sucked into the gravitational pull of my terrible smile, a smile that never made it on-camera once upon a time.

I say, “Your cousin didn’t know anyone who was there, and let’s not pretend otherwise.”

He blinks behind his sunglasses. Even though I can’t see his eyes I know that look. My power play is a form of mesmerism: calling out the liars as liars without having to use the word.

I break the spell by asking him if I can borrow ten bucks for parking because I don’t have any cash on me, which may or may not be true. How to win friends and influence people, right?

Listen, I’m a nice person. I am. I’m honest, polite, giving when I can be, commiserative, and I’ll give you the white T-shirt off my back if you need it. I can even tolerate being buried in bullshit; it comes with my fucked-up gig. But people lying about being on Horror Movie’s set gets to me. I’m sorry, but if you weren’t there, you didn’t earn the right to say you were. It’s less narcissism on my part (though I can’t guarantee there’s not a piece of that in there; does a narcissist know if they are one?), and more my protecting the honor of everyone else’s experience. Since I can’t change anything that happened, it’s all I can do.

Our movie did not feature a crew of hundreds, never mind tens, as in multiple tens. There weren’t many of us then, and, yeah, there are a lot fewer of us still around now.

2Then:The First Day

The first day of filming was June 9, 1993. I don’t remember dates, generally, but I remember that one. Our director, Valentina Rojas, gathered cast and crew. Except for Dan Carroll, our director of photography and cameraman, who was somewhere in the yawning desert of his thirties, the rest of us were stupid young; early or mid-twenties. I mean “stupid” in the best and most envious ways now that I am over fifty. Valentina waited like a teacher for everyone to quiet down and settle into a half circle around her. After a bit of silence and some nervous giggles, Valentina gave a speech.

Valentina liked speeches. She was good at them. She showed off how smart she was, and you were left hoping some of her smartness rubbed off on you. I enjoyed the rhythm and lilt of her Rhode Island accent that slipped out, maybe purposefully. If she sounded full of herself, well, she was. Aggressively, unapologetically so. I admired the ethos—it was okay to be an egomaniac or an asshole or both if you were competent and weren’t a fucking sellout. Back then, nothing was worse than a sellout in our book. Compromise was the enemy of integrity and art. She and I kept a running list of musical acts who rated as sellouts, eschewing the obvious U2, Metallica, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, which were givens, for subtler, more nuanced choices, and she’d include our local UMass–Amherst heroes, the Pixies, on her list just to piss off anyone eavesdropping on us.

I mention this now, in the beginning, as our passing collegiate friendship (I’m too superstitious or self-conscious, I can’t remember which, to rate it as a full-fledged relationship) was why I was cast as the “Thin Kid.” That and my obvious physical attributes, and a thirst for blood.

I know, the blood crack is a fucking awful joke. If that joke bothers you, I get it. Don’t you worry, I hate me too. But listen, if I’m going to tell any of this, I must do it my way, otherwise I’d never get out of bed in the morning. No compromise.

With our small army gathered on the shoulder of a wide suburban dead-end road, Valentina reiterated the plan was to shoot the scenes in the film’s chronological order, each scene building off the prior one until we made it to the inevitable end. Valentina said we had four weeks to get it all done, when she really meant five. No one corrected her.

I hung out in the back of the circle, vibrating with nervousness and a general sense of doom. Dan whispered to me, not unkindly, that Valentina’s mom and dad wouldn’t pay for week five. Dan was a short, wiry Black man, exacting but patient with us film newbies and nobodies. He co-owned the small but well-regarded production company that shot and produced commercials as well as the long-running Sunday-morning news magazine for the Providence ABC affiliate. I smiled and nodded at his joke, like I knew anything about the budget.

Valentina ended her spiel with “A movie is a collection of beautiful lies that somehow add up to being the truth, or a truth. In this case an ugly one. But the first spoken line in any movie is not a lie and is always the truest.”

Valentina then asked Cleo if she had anything to add. Cleo stood with an armful of mini scripts for the scenes being shot that day. In filmmaking lingo, these mini scripts are referred to as “sides.” Mine was folded in the back pocket of my jeans. The night before had been my first opportunity to read the day’s scenes.

Cleo had long red hair and fair skin. She was already in wardrobe and looked like the high schooler she would be playing, preparing to make a presentation in front of the class. Cleo couldn’t look at

and spoke with her eyes pointed toward the pavement under our feet.

She said, “This movie is going to be a hard thing to do. Thank you for trusting us. Let’s be good to each other, okay?”

HORROR MOVIE

Written by

Cleo Picane

EXT. SUBURBAN SIDE STREET – AFTERNOON

The street is a tunnel. Its walls are two-story homes on wooded lots. The interwoven, incestuous tree branches and green leaves hoard the sunlight and form the tunnel’s ceiling.

That the houses are well kept and front lawns and shrubs groomed are the only visible signs of human occupancy. This suburban neighborhood is a ghost town -- no, it’s a picturesque hell so many desperately strive for, and so few will escape.

Four late-high-school-aged TEENS walk down the middle of the road, one that sees little traffic. There are no yellow lines, no demarcated lanes, which offers the illusion of freedom.

VALENTINA (she’s short, thick curly black hair spills out from under a knit beanie, eyeliner rings her downturned eyes, she walks heavily in chunky boots, wears black and gray baggy clothes, the baggiest of baggy clothes, her high school survival camouflage, she imagines the clothes make her if not invisible then ignorable to classmates).

CLEO (dresses like the rest of her classmates, which is a more effective high-school-survival camouflage than Valentina’s, she has long red hair pushed off her forehead with a headband, wide-lensed glasses, jeans pegged at the ankles above her white high-top Chuck Taylors, a firetruck-red blazer over a horizontal black-and-white-striped top, Cleo does well in school and struggles with depression and she only leaves her bedroom for school or to hang out with her three friends). Cleo carries a crinkled grocery PAPER BAG.

KARSON (average build and height, slumped shoulders that might one day be broad, he wears overalls because he thinks they make him look taller, overall straps are clipped over a charcoal-gray sweatshirt ripped and frayed around the collar, his dark-brown hair is long in the front and his head is shaved on the sides and back, he has a nervous tic of running his hands through his bangs).

Valentina, Cleo, and Karson walk in a line, a breezy, step-for-step choreography. When no one else is around to see and judge them, they are rock stars.

The three teens don’t talk, but they take turns knocking

into the person next to them, then passing the hip-bump along while laughing and never breaking the formation. They are, in this moment, unbreakable. Their friendship is beyond language. Their friendship is a perpetual-motion engine. Their friendship is easy and gravid and intense and paranoid and jealous and needy and salvatory.

A fourth teen, the THIN KID, lags, languishes behind their line. He blurs in and out of our vision like a floaty in our eyes.

We do not, cannot, and will not clearly see the Thin Kid’s face.

But we almost see him, and later, we will have a false memory of having seen his face.

That face will be built by what isn’t seen, built from an amalgam of other faces, faces of people we know and people we’ve seen on television and movies and within crowds. Perhaps we’ll imagine a kind face when it is more likely he has a face, to our enduring shame, that does not inspire our kindness.

There will be glimpses of the Thin Kid’s jeans, the color too dark, too blue, and his long feet sheathed in sneakers that are cheap, generic, not cool within any subculture.

There will be a clear shot of his pale matchstick arms, slacken ropes spooling out from the billowing sail of a white T-shirt, logo-less, as though he hasn’t earned the right to wear a brand.

There will be a blur of shaggy brown hair and his rangy profile in an out-of-focus blink.

The Thin Kid walks behind the three teens, out of step, out of time, working harder than they do, and he’s walking faster than they are, but he will not overtake them, nor will he catch them.

Cleo looks over her shoulder, once, at the Thin Kid.

Her easy smile fades, and she clutches the paper bag more

tightly.

EXT. DEAD-END STREET/FOREST LINE – MOMENTS LATER

The teens stop walking at the end of the dead-end street, at the mouth of an overgrown path into the WOODS.

A pair of TRAFFIC CONES and a rickety WOODEN HORSE block the entrance.

KARSON

(eyes only for the path)

Are you sure this is the

right way?

VALENTINA

(pushes sleeves over

her angry hands)

You’re the one who said you

used to ride your bike there

and did laps around it until

you popped a tire.

KARSON

(stammers)

Well, yeah, but that was a long

time ago, and I’m pretty sure

I got there a different way.

Valentina curls around the cones and horse and onto the path. Her sleeves accordion back over her hands.

VALENTINA

This is the way

we’re going.

Karson shrugs, runs his hands through his hair, follows.

Cleo is next onto the path.

She pauses, reaches across the barrier, reaches for the Thin Kid’s hand.

We see him from behind. We do not see his face. We do not see his expression. We cannot know what he is thinking, but maybe we can guess.

The Thin Kid stuffs his hands into his pockets petulantly, or playfully.

CLEO

(whispers, neither

patient nor impatient)

Come on. Let’s go. Trust

your friends.

The Thin Kid does as she says and steps onto the path.

EXT. FOREST PATH – MOMENTS LATER

The path is overgrown and narrow. They walk single file. They lift wayward branches or crouch under them.

KARSON

What if there are other

kids there?

VALENTINA

There won’t be.

KARSON

How do you know? You don’t

know.

Valentina hooks an arm through Karson’s arm. With her sleeve-covered hand, she pats the crook of

his elbow.

She’s being both condescending and a good friend, acknowledging and downplaying his well-founded fears of “other kids.”

VALENTINA

Hey. We’ll be all right.

Cleo holds up and shakes the paper bag, like it’s a town crier’s bell, like it’s a warning.

CLEO

(uses an exaggerated

deep voice, her

father’s voice)

We’ll just scare those

punks away, and give them

what-for.

Valentina laughs.

Karson shakes his head and mumbles to himself, and when Valentina detangles away from their linked arms, he squeezes the top of her beanie hat, makes a HONK sound, then grabs and pulls the end of her sleeve, stretching it out like taffy.

Valentina mock screams, spins, and slaps him across the chest with the extra cloth.

THIN KID

Why am I--

VALENTINA

(interrupts)

There’s no “why.” I’m sorry,

there never is.

This is important: she isn’t mocking the Thin Kid, and she doesn’t sound mean or aloof. Quite

the opposite. Valentina sounds pained, sounds as sad as the truth she uttered.

She cares about the Thin Kid.

Cleo and Karson care too. They care too much.

The Thin Kid plucks LEAVES from the branches they pass and puts them in his pockets.

3Then:The Pitch Part 1

In mid-April of 1993 Valentina left a message on my apartment’s answering machine. We hadn’t talked for almost two years. She got the phone number from my mother, who was awful free with those digits, if you ask me. Valentina said she had a proposition, laughed, apologized for laughing, and then she assured me the proposition was serious. How could I resist?

She and I didn’t go to college together, but we’d met as undergrads. I bused tables and worked at Hugo’s in Northampton, a bar that was close enough to campus that my shitbox car could survive the drive and far enough away that I wouldn’t have to deal with every knucklehead who went to my school. One weeknight when the bar wasn’t packed, I was stationed by the door and pretended to read a dog-eared copy of Naked Lunch (cut me some slack, Hugo’s was that kind of place in that kind of town), and Valentina showed up with two friends. Her dark, curly hair hung over her eyes. She wore a too-big flannel shirt, the sleeves hiding her hands until she wanted to make a point, then she pointed and waved those hands around like they were on fire. She was short, even in her thick-heeled combat boots, but she had physical presence, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved