- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

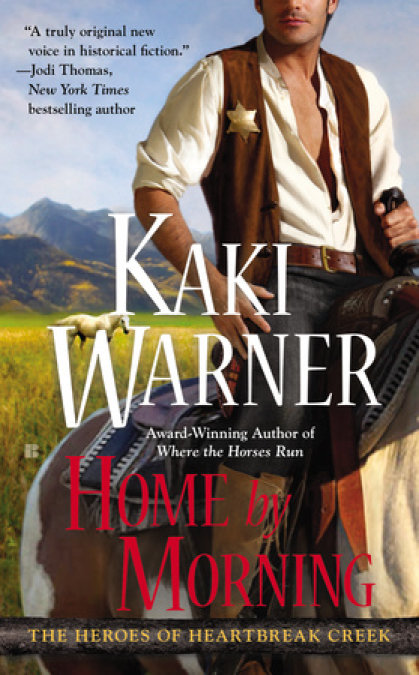

The award-winning author of Where the Horses Run makes her eagerly anticipated return to Heartbreak Creek for the final book in a trilogy of soul-stirring historical romance.

Thomas Redstone—a former Cheyenne warrior seeking new purpose by following the ways of his white grandfather—is returning to Heartbreak Creek, Colorado, when he decides to give the woman he loves one last chance to accept him into her life.

Prudence Lincoln’s beauty and education have brought her little joy. Envied by blacks for the advantages she’s had, and reviled by whites for her mixed blood, she’s proving herself by helping ex-slaves prepare for newfound freedom. Thomas has no place in her future, no matter how much she loves him.

He’s suffered only hardship. She was raised in privilege. Their only common ground is the spark between them that won’t die. Yet even as evil forces tear them apart again, they discover that courage can be a weapon, happiness is a choice, and love can triumph over anything.

Release date: July 7, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Home by Morning

Kaki Warner

KAKI WARNER, 2011 RITA WINNER FOR BEST FIRST BOOK FOR PIECES OF SKY, IS “A GIFTED STORYTELLER.”*

Part One

What is life?

It is the flash of a firefly in the night.

It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime.

It is the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset.

—Crowfoot, Blackfoot warrior and orator, 1830–1890

Prologue

In an eagle is all the wisdom in the world.

—Native American proverb

SCHULER, INDIANA, NOVEMBER 1871

Squinting against bright morning sunlight, Prudence Lincoln stood at the library window of the Friends School for The Betterment of People of Color and studied the letter in her hand.

“. . . rise from your dreams, Voaxaa’e, and together we will fly away.”

What did that mean? She knew Voaxaa’e was the Cheyenne word for eagle, a fanciful name Thomas had given her months ago. But fly away where? Back to Heartbreak Creek?

Their last meeting had been horrid. When she had told him she still had work to do here at the school and needed to stay longer in Schuler, he had allowed his anger and frustration to show. It was the first time Thomas had ever raised his voice to her, and it had frightened her, awakened old memories she still fought hard to keep buried. She had reacted without thinking. When he had seen her cowering before him, arms raised in defense, he had been stunned. Then hurt. And without allowing her to explain, he had walked out the door and had never come back.

Pru’s half sister had written from Heartbreak Creek that he had gone to Britain with Ash and Maddie Wallace to purchase thoroughbreds. But she hadn’t heard a word from Thomas.

Terrified that she would never see him again, she had written to him in England, trying to explain her fears.

And now, months later, he responded with this? Bemused, she read again the words written in the familiar bold script she had taught him back in the one-room schoolhouse in Heartbreak Creek, Colorado Territory.

“Look for me, Prudence Lincoln. When the wind blows cold and the Long Night’s Moon rides in the sky, I will come to you. Listen for my voice in the shadows. Then rise from your dreams, Voaxaa’e, and together we will fly away.”

She didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

“Are you ready?” a voice said behind her.

Turning, she saw Cyrus Marsh standing in the doorway beside her valise, one gloved hand on his hip, holding back his overcoat, the other gripping the brim of the hat he tapped impatiently against his leg.

“I can’t go, Mr. Marsh.” As she spoke, she slipped the letter into her coat pocket, not sure why she didn’t want him to see it. She disliked Mr. Marsh, and had from the moment they had met. Despite his practiced smiles and polite words, she sensed an undercurrent of coldness within him.

“Oh?” His blond brows rose in arcs above eyes of such a pale hazel they seemed yellow against his sallow skin. “I’m sorry to hear that, Miss Lincoln. We’ve gone to a great deal of trouble to make arrangements for you to join us on this trip. May I ask why, at the moment of our departure, you feel you can’t go?”

“I’m expecting a visitor. He’s coming a long way, and I wouldn’t want to miss him.”

“Your Indian friend.” His voice carried no emotion, but she saw the slight curl in his thin lips. “A woman as beautiful as you, Miss Lincoln, shouldn’t waste herself on an ignorant savage.”

Pru’s chin came up. “Mr. Redstone is neither ignorant nor savage.” Most of the time, anyway.

The hat tapped harder, faster.

Behind him, a small figure moved silently through the hall.

Lillie. Eavesdropping again. Pru would have to speak to the girl. Not that it would help. The child had little enough to keep her insatiable curiosity and bright mind occupied, and listening in on the lives of others was her dearest pastime. At least the girl was honorable enough not to repeat the things she heard.

“When do you expect him?” Mr. Marsh asked.

“When the wind blows cold and the Long Night’s Moon rides in the sky.”

“Mid-December,” she guessed. “I’m not sure of the exact date.” Possibly around the twenty-first, since that would be the longest night of the year. Thomas’s colorful speech was often difficult to decipher.

“Perhaps you could write back and ask him to delay the visit.”

“I wouldn’t know where to reach him.” Pru realized she was rubbing her fingers over the scars on her right wrist and made herself stop. Confrontations made her nervous. Bad enough that Mr. Marsh ordered Brother Sampson around as if he were still a slave, but to have him interfering in her life was intolerable. She had never been a slave, despite her mixed blood, and was unaccustomed to such treatment. Still, as trustee of the school that employed her, he deserved at least a show of respect. “He’s traveling from England, you see.”

At least that’s what Maddie’s latest letter had said. The freighter carrying the thoroughbreds, Thomas, and the Wallaces’ wrangler, Rayford Jessup, was scheduled to arrive in Boston near the middle of this month. From there, they would travel by rail to Colorado, with stops along the way to rest the horses, which would drag out the journey for several weeks or more. Maddie had concluded by saying she assumed Thomas would stop to visit her on his way through Indiana, and for Pru to expect some changes.

Changes? In Thomas? He was solid as a rock. He certainly had no need to make changes.

“If he’s not due until mid-December,” Mr. Marsh said, regaining her attention, “that would still leave us ample time to accomplish our purposes in the capitol. I see no problem.” Looking pleased, he set his hat on his head. “I’ll instruct the school administrator to send word if your Indian arrives before we get back. But should he do so, you can leave a note, telling him you’ll return shortly. Schuler is only a six-hour train ride from Indianapolis.”

“But things could have gone more smoothly than anticipated,” Pru argued. “He might arrive any day. I would like to be here if he does.” Being Thomas, if he did arrive and found her gone, he might simply leave. He had a habit of disappearing when things weren’t to his liking.

“Miss Lincoln.” Marsh paused as if struggling with words—or his temper. Marsh hated to be contradicted, especially by a woman. “You know how important this trip is. Not only for Brother Sampson, but for your education initiative, as well.”

“Yes, but—”

“And with backing from important key people in Indianapolis,” he went on, ignoring her protest, “the two of you can advance equality and education for blacks more than the Quakers have ever done.”

“I understand that, and I—”

“Our efforts could reach all the way to Washington. Isn’t that what you want? What we all want?”

“Certainly, but—”

“For God’s sake, then why are you defying me? Do you think I’ll allow you to ruin everything because of a damned Indian?”

Pru shrank back, old fears flooding her mind.

“Christ.” Dropping his hands to his hips, Marsh let go a deep breath.

Moments passed. Tension weighted the air while Pru stood locked in fear, waiting to see what he would do next. Breathe. Show no fear.

When he finally spoke again, his voice was as cold as the glint in his near-colorless eyes. “I didn’t want to have to resort to threats.”

Threats?

Tipping his head to the side, he said in an almost conversational tone, “I know what you’ve been up to, Miss Lincoln.”

Fear ballooned into an almost overwhelming urge to flee. How could he know? How did he find out? “I-I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you?” His smile showed small, pointed teeth. A predator’s smile. “I know the Underground Railroad has started up again. Only this time, it’s not to aid runaway slaves seeking freedom, but to help black felons and agitators escape into Canada. The misguided fools helping them could go to jail. Or worse. I know you’re involved, so don’t bother to deny it.”

She didn’t. “They only want to live free, Mr. Marsh. Instead of being brutalized in the name of Southern Reconstruction.”

He waved a hand in dismissal. “Save your speeches. If I could, I would turn the lot of you over to the authorities today.”

Perspiration gathered under her arms. “Why do you care if a few desperate colored people seek a better life?”

“I don’t. But I do care about Brother Sampson and your education initiative.” He leaned toward her, that icy gaze eroding her courage. “The more people who flock to hear him preach, the more exposure your cause will get, and the more opportunities will come my way. A grand future awaits us all . . . as long as there are no scandals. No untoward attention. Nothing to raise questions or generate doubt. Voters can be so fickle.”

The hairs on the back of her neck lifted. This was about votes?

“You’re an intelligent woman, Miss Lincoln, especially for one of your race. Surely you’re aware that you and Brother are my stepping-stones to the real power in Washington. I’ve invested a great deal of time and effort toward that goal, and I will not allow anything to jeopardize those plans.”

He moved closer, his yellow eyes burning with the fervor of a fanatic. “So be warned, Miss Lincoln. Behave. Stop this foolish business with the railroad, because if you persist, I will exact a terrible price, if not from you, then from someone dear to you. One of your students, perhaps. Or your Indian. Maybe even Brother Sampson. But rest assured, someone will pay. Do you understand?”

Pru fought to drag air into her lungs. He’s insane. Evil, like Satan is evil. Just being near him made her feel unclean.

Another step. “Have I made myself clear, Miss Lincoln?”

Pru nodded.

He studied her for a moment, then stepped back, his smile once more in place. “Then we’ll speak no more of it.” Bending, he picked up her valise. “While I put this in the carriage, you write that note to your Indian. When I return, I’ll take it to the administrator, along with my instructions to wire us if Mr. Redstone arrives before we return. And do hurry, Miss Lincoln. Brother Sampson is waiting, and you know how the cold aggravates his hands.”

Light-headed and shaking, Pru watched him leave the room. Terror careened through her mind, muddled her thinking. But one thought kept surfacing. After she finished this last rescue through the railroad, she would tell Brother Sampson about Marsh’s motives. Perhaps together they could find a way to stop him. But for now, and for his own safety, she had to send Thomas away.

And there was only one way to do that.

The pain of it almost doubled her over.

On leaden legs, tears streaming, she went to the desk by the window and extracted a piece of paper from the drawer. Struggling to keep her hand steady, she wrote . . .

Dear Thomas,

I fear you misunderstood my last letter to you. I am not seeking a reunion. Our last visit made it clear to me that despite the deep feelings I have for you, we come from such different worlds we could never build a solid future together. I am sorry. Please give everyone my regards when you return to Heartbreak Creek.

I will always remember you fondly.

Prudence Lincoln

One

INDIANA, DECEMBER 1871

With an unaccustomed twinge of nervousness, Thomas Redstone paused at the gate in front of a large brick building on the outskirts of Schuler, Indiana. He studied the words on the sign planted in the front yard. With the help of Rayford Jessup, his reading had improved, but it was still troublesome, and he wanted to be certain the sign had not changed since his last visit. It had many words.

The Friends School for the Betterment of People of Color. It was the same.

From inside the building came the distant voices of children chanting their numbers. He pictured Prudence Lincoln standing before them, smiling as she had once smiled at him, her oldest pupil.

Had she received his letter? Would she welcome him? Or would she choose these strangers over him once again, and send him away with more excuses? If so, it would be the last time. He could not spend the rest of his life waiting for her to accept him. If she turned him away this time, he would not come back.

He did not want to think of how empty his days would be if that happened.

Pushing the thought aside, he brushed back his shoulder-length hair and tugged the collar away from his neck so he could breathe. As he walked toward the front porch, he looked around.

The yard was bare but for a leafless willow tree. There was no snow on the ground, and few clouds hung in the sky. Even though it was early morning, the breeze off the Ohio was so gentle it felt like a cool hand against his cheek. Much warmer than in Colorado. For a moment, the horizon beckoned, and the call to return home was strong in his mind. He had been gone many months and had traveled far. He wanted to go back to his snowy mountains.

But first, he must see Prudence Lincoln.

When he started up the steps, he saw a black-skinned girl-child sitting in a chair on the far end of the porch, staring in his direction. She looked small and thin beneath her worn coat, and probably had less than a dozen years. She was darker than Prudence Lincoln, and tiny ribbon-tied braids sprouted from her head like raven feathers from a war bonnet. He wondered why she was not at her lessons with the other children.

“Mornin’,” she called. “My name Lillie. It really Lillian, but ev’rybody only call me Lillie.”

He nodded without speaking. Setting down the leather pouch holding his extra clothes, he stared at the closed door, that uneasiness rising in him again. He did not like it. Did not like the feeling of doubt that came with it. Irritated at such weakness, he smoothed a hand down the front of his jacket. He did not like these fancy clothes the Scotsman had bought for him, either. Or the boots he had to wear instead of his moccasins. He missed his topknot and eagle feather.

But to honor his white grandfather—and Prudence Lincoln, who was half white—this was the path he had chosen. For now. But once he returned to his mountains, he would cast aside these foolish trappings and become Cheyenne once again.

“Ain’t you gonna knock?” the girl called.

He scowled at her for interrupting his thoughts.

She seemed not to notice and continued to stare, her head cocked to one side.

He took a deep breath, let it out, then lifted his fist and pounded on the door.

He stepped back and waited.

Footsteps approached. He stood stiffly as the door opened and a stern-faced old woman in a plain brown dress looked out at him. He did not recognize her from before, when he had left Prudence Lincoln in anger and sailed across the wide water to buy horses.

“How may I help thee?” she asked.

A Quaker. He remembered the strange way they spoke. “You will take me to Prudence Lincoln.” Seeing the woman’s mouth tighten, he added, “Please.”

“Miss Lincoln is not here.” The woman tried to close the door.

Thomas stopped it with his hand. “Where is she?”

She blinked round, dark eyes, reminding Thomas of a tiny brown wren. “I was told they went to the capitol.”

They? And what was this capitol?

This time, she shut the door before Thomas could stop her. “Noxa’e! Wait!”

The footsteps faded into silence.

Muttering, he turned to find the girl rising from her chair.

“I knows you.” She reached out to touch the porch rail. “You her Indian, ain’t you? Thomas Redstone.” She walked closer, one hand on the railing, the other pointed his way. “You a Cheyenne Dog Soldier.”

He saw nothing familiar in the girl’s face, or in the odd way she looked toward him, but not at him. She spoke like other black skins he knew who had been slaves. Not like Prudence Lincoln. She had never been a slave, and her white father had raised her to speak in the white way. The proper way, she called it.

Thinking this girl—proper or not—might be more help than the Quaker woman, he put on a smile. “I did not see you when I came here before.”

“I not see you, neither,” she said and giggled.

Then he understood. Her careful gait. That blank stare. The intent way she listened, her head tilted to one side to catch every sound. “You cannot see.”

“Scarlet fever. Three years back when I eight. You sounds tall.”

“If you cannot see me, how do you know who I am?”

She continued toward him. When the fingertips of her outstretched hand brushed his coat, she stopped and let her arm fall back to her side. “You talk different from the Friends. Or Miss Pru. Or anybody.” She smiled at his chest. “Can I feel you face?”

He drew back. “Why?”

“That how I learn what you look like.”

Forcing down his natural wariness around those marked by the Great Spirit, Thomas bent to within reach of her hands.

Her touch was as soft as a moth’s wings. And ticklish. But he stood motionless while she felt everything, even his ears and lips and eyes. When she finally took her hands away, he straightened, glad the ordeal was over. He was not comfortable with such touching, except with Prudence Lincoln. He liked to keep people far enough away that he could see all of them at once and know if a threat was coming. “What did you learn?” he asked.

Another giggle, showing a gap where a front tooth had been. “You gots a big nose and you eyebrows very stern. What color you eyes?”

“Dark, and my nose is not big. What is this capitol the Quaker woman spoke of?”

“Indianapolis. I go there ’fore I blind. It a big place, sho’ ’nuff. What color you hair?”

“Black. Why did Prudence Lincoln go there?”

“To raise money for Reverend Brother Sampson and talk ’bout schoolin’ fo’ black folk.” A spark lit the blankness in her brown eyes. “You fetchin’ her? She ’posed come back long time ago, but she ain’t showed.”

Thomas stared past her, plans already forming. If he fetched Prudence Lincoln, it would not be to bring her back here.

“Oh. Well.” A deep sigh. “They not let you take her, anyways.”

He glared down at her dark head. “Who would stop me?”

“Mistuh Marsh. He say Reverend Brother Sampson need her.”

“Tell me of these men.”

Leaning over the rail, she groped until her hand brushed a shrub planted beside the porch. Plucking a withered blossom, she sniffed it, then slipped it into her coat pocket before moving down the rail to another plant. “Reverend Brother Sampson a preaching man. He a slave in Kentucky ’fore he come here on the Underground Railroad. Now he preach the Holy Gospel in a big tent. He nice. Always bring me peppermints.”

“And the other man?”

She plucked another dead blossom, sniffed, then put it in the pocket with the first. “Mistuh Marsh. He white.” Her voice changed. Held a trace of . . . fear? “He take Reverend Brother Sampson ’round so he can preach. This time, he take him to Indianapolis. Miss Pru say folks there maybe send him all the way to Washington to talk to the President.”

Thomas knew what a talk with the White Father in Washington meant. More treaties, more broken promises, more trouble for the People. “Why do they need Prudence Lincoln to do this?”

“’Cause she smart. Mistuh Marsh say with her by his side, folks maybe like Reverend Brother Sampson ’nuff to make him a leg-a-slater. I ain’t sure what that is. Nobody tell me nothin’ ’round here. They think ’cause I blind, I stupid, too.”

Thomas frowned. “And Prudence Lincoln? Does she like Reverend Brother Sampson, too?”

“’Course. Everybody do. Even the Friends.”

A coldness gripped him. Did that mean she had chosen this man over him? He did not want to believe that. Prudence Lincoln was his heart-mate. But why, then—after he wrote to her that he was coming—was she not here? What was he to do now? Wait for her until he grew old and his days ran out?

He could not do that. He would not live his life that way. Better to walk away now than to be sent away later.

Fury burned away the chill. But it also awakened that part of him too stubborn to give up . . . not even when he hung in agony from the ropes during the Sun Dance ceremony . . . or when he saw his chief killed and the People driven from their lands onto government reservations . . . or when he searched tirelessly, despite his wounds, to find Prudence after the Arapaho renegade took her.

He would not walk away this time. He would go to this other place—this Indianapolis. He would find Prudence Lincoln and tell her what was in his heart. Then he would go back to his mountains. If she chose to stay here, that would be the end of it. He would put her from his life forever.

If he could.

He looked down at the girl staring blankly across the yard, her thin fingers tugging at a loose thread on her worn cuff. “Where is this place called Indianapolis?”

She looked up.

Her eyes might be blank, but he sensed a sharp intelligence hidden behind them. This girl was not stupid.

“You go after her? ’Cause I tell you how to get there. I even get you a map.” She leaned closer to whisper at his jacket. “But you gots to take me with you. Miss Pru need both us to get her away from Mistuh Marsh.”

Thomas almost smiled, amused that she thought he needed help from a blind girl who probably weighed little more than his bag of extra clothes. “I cannot take you with me.”

Chin jutting, she crossed her arms over her chest. “Then I ain’t helpin’.”

“Goodbye, Lillian.” He picked up his leather bag.

“Where you goin’?”

He started down the steps into the yard.

“You cain’t jist leave me!” She stumbled forward, hands clutching at air. “A po’ blind black girl who ain’t got nobody to look out for her, not even a dog to lick away her tears!”

“Go inside, Lillian,” he called over his shoulder.

“Don’t go!” She flung herself toward him.

With a curse, he dropped the bag and caught her before she flew headfirst down the steps. “You foolish ka’eskone,” he scolded, setting her back on her feet. “You could have hurt yourself!”

Behind him, the door swung open. A man in a dark collarless coat over a plain white shirt stepped onto the porch. “What’s going on out here? Lillie, what mischief have thee gotten into this time?”

When she tucked her head without answering, the Quaker turned his attention to Thomas. “I am Friend Matthews,” the older man said. “Administrator of the school. Who might thee be?”

“Thomas Redstone.”

“The man seeking Miss Lincoln?”

Thomas nodded.

“Weren’t you told she was in Indianapolis?”

“Yes, but I was not told when she will come back.”

“We don’t know when she’ll be back.”

Thomas thought for a moment. “She knew I would come. She left no message for me?”

“None that I am aware of. I am sorry, friend.” Turning to the girl, he held out his hand. “Come along, child.”

“No.” The girl fumbled until she found Thomas’s hand. Taking it in both of hers, she grinned at the Quaker’s stomach. “I’m going with Daddy.”

Ten minutes later, Thomas walked back toward the Schuler train station, this time with two bags of clothes and a beaming little black girl by his side.

“I know’d you catch me ’fore I fall down the steps,” the girl said, clinging to his arm as they walked along the road. “You a good daddy. Gots any other chilrin ’sides me?”

“No. And I am not your father.” He had spoken those words many times . . . to her, the Quaker, and to anyone else who would listen before they were gently, but firmly, herded out the door. The people at the school seemed eager to send the girl away with him. He could guess why.

“I knows you ain’t.”

“Then why did you tell them I was?”

“’Cause I need a daddy and they wouldn’t let me go with you if you wasn’t. Slow down. I’m just a po’ little blind girl, ’member?”

More like heavoheso—a devil—in pigtails. Reining in his temper, Thomas slowed his pace. He did not know what to do with this strange child. He was not a nursemaid. “Where are your parents?”

“You mean ’sides you?”

“I am not your father.”

“Don’t know where my other daddy is. He sold off ’fore I born. Mama gone to Jesus. Drowned. Up and walk out the field one day, straight into the river. Overseer find her floatin’ in the weeds. You know skin turn white and come off you stay in the water too long?”

Thomas kept walking, not sure what to say. The girl had lied about him being her father. Maybe she lied about this, as well. He hoped so.

“Mama always want to be white. Guess she got her wish. She make a pretty white lady, sho’ ’nuff. Miss Pru pretty?”

“Yes.”

“That probably ’cause she half white.”

Thomas smirked at the notion. “It is not the color of her skin that makes her pretty. It is the goodness in her heart.” And her smile. And the way she looked at him when he touched her. Would he ever hold her against him again?

“After your mother died, who took care of you, Lillian?”

“Whoever around. When the fightin’ stop, Friends come and bring us to freedom lan’. Been here since. They nice, even if they talk funny.”

They talk funny? Thomas wondered what Prudence Lincoln thought about the way this girl spoke. He remembered how she had sat beside him, pointing out the letters in her book and teaching him to speak in the proper way. He had not been a good student. It was hard to think about words when she sat so close.

“Hey,” the girl said, giving his hand a yank to get his attention. “Since I be your little girl, my name Lillie Redstone now?”

Thomas did not answer.

After a while, they turned onto a side road that ran along the railroad tracks. Up ahead, the depot squatted like a beetle beside a spindly water tower balanced on eight skinny wooden legs. A beetle and a hungry spider. He felt caught in a web, too. He still was not sure what to do when the train came. He could not leave the girl by the tracks. And he could not take her back to the school. Maybe when he found Prudence Lincoln . . .

“She not fo’get.”

He looked down at her. “What?”

“Miss Pru. She not fo’get you comin’. She leave you a note, but Mistuh Marsh not give it to Friend Matthews like he say he do.”

Thomas smiled. She had remembered.

“And he mean to Miss Pru. Take her to Indianapolis when she want to wait for you. Say she better behave. He a mean one, make Miss Pru cry like that.”

Cry? Thomas’s steps slowed. Eho’nehevehohtse rarely cried. Not even after he freed her from Lone Tree. Or when she tended him after he was shot, and he heard her awake from night terrors. Who was this man and why did he warn her to behave? Prudence Lincoln always behaved. When Thomas was with her, that was his hardest task—to convince her not to behave.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...