Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Chapter 1 - Après Macbetto

Chapter 2 - In Search of Guacamole

Chapter 3 - Vladik in Trouble

Chapter 4 - “Our Cultural Establishment Has Suffered A Great Loss”

Chapter 5 - Adela Distraught

Chapter 6 - Questions Abound

Chapter 7 - A Meeting of Incompatibles

Chapter 8 - Was He Murdered?

Chapter 9 - Indignant Ladies Unite

Chapter 10 - Indignant Ladies vs. Sergeant Guevara

Chapter 11 - Sources of Information

Chapter 12 - Talking Dirty

Chapter 13 - Lunch with Russians

Chapter 14 - Home Sweet Trailer Park

Chapter 15 - On Consulting with an Irritable Spouse

Chapter 16 - Approaching Brazen Babes

Chapter 17 - The Good Works of Opera Lovers

Chapter 18 - Dr. Tigranian Hears Bad News

Chapter 19 - Brazen Babes

Chapter 20 - “Who’s Prissy?”

Chapter 21 - Calling Around

Chapter 22 - The Ad Hoc Committee at Work

Chapter 23 - How to Catch Salvador Barrientos

Chapter 24 - Protecting Academia

Chapter 25 - Parallel Parking and World-Class Margaritas

Chapter 26 - Mariachi Caliente

Chapter 27 - Stake Out

Chapter 28 - The Capture

Chapter 29 - Bounty Hunters

Chapter 30 - A Night at the Jail

Chapter 31 - Targeting Boris

Chapter 32 - The I-Got-Kids Excuse

Chapter 33 - The Hit Man’s Ex

Chapter 34 - Boris Loses It

Chapter 35 - First Black Eye

Chapter 36 - A Butt Print Remembered

Chapter 37 - Canvassing in Black and Blue

Chapter 38 - Going Behind Sergeant Guevara’s Back

Chapter 39 - Anxious Relatives From Juarez

Chapter 40 - Recipe Strategy

Chapter 41 - The Investigation Moves Elsewhere

Chapter 42 - News Al Fresco

Chapter 43 - Hearsay Confession

Chapter 44 - He Said, She Said

Recipe Index

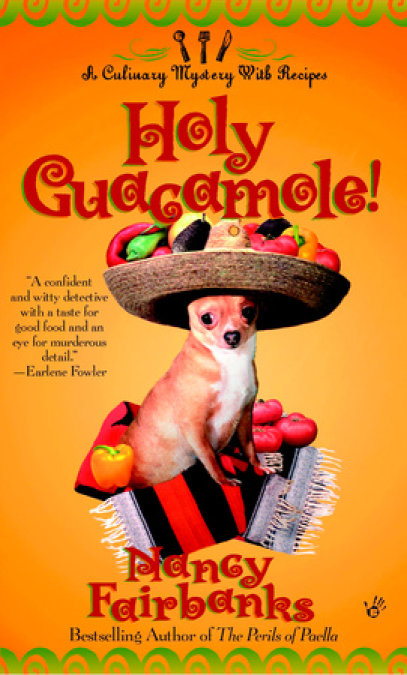

Praise for the delectable Culinary Mysteries by Nancy Fairbanks . . .

“Clever, fast-paced ... A literate, deliciously well-written mystery.”—Earlene Fowler

“Not your average who-done-it ... Extremely funny ... A rollicking good time.” —Romance Reviews Today

“Crime Brûlée is an entertaining amateur sleuth tale that takes the reader on a mouth-watering tour of New Orleans . . . Fun.” —Painted Rock Reviews

“Fairbanks has a real gift for creating characters based in reality but just the slightest bit wacky in a slyly humorous way . . . It will tickle your funny bone as well as stimulate your appetite for good food.” —El Paso Times

“Nancy Fairbanks has whipped up the perfect blend of mystery, vivid setting, and mouthwatering foods . . . Crime Brûlée is a luscious start to a delectable series.”

—The Mystery Reader

“Nancy Fairbanks scores again . . . a page-turner.”

—Las Cruces Sun-News

Berkley Prime Crime titles by Nancy Fairbanks

CRIME BRÛLÉE

TRUFFLED FEATHERS

DEATH À L’ORANGE

CHOCOLATE QUAKE

THE PERILS OF PAELLA

HOLY GUACAMOLE!

MOZZARELLA MOST MURDEROUS

BON BON VOYAGE

Anthologies

THREE-COURSE MURDER

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books, Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty., Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—

110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand, Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196,

South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the

author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,

business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

HOLY GUACAMOLE!

A Berkley Prime Crime Book / published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Berkley Prime Crime mass-market edition / November 2004

Copyright © 2004 by Nancy Herndon.

eISBN : 978-1-101-01045-7

Grateful acknowledgment is made to W. Park Kerr and Norma Kerr for permission to reprint copyrighted recipes from the El Paso Chile Company’s Texas Border Cookbook, William Morrow and Co., Inc, 1992

For

Donna, Ken, and Katy Katschke

Author’s Note

Opera at the Pass and its members and singers are all fictitious, as are the plot and all characters except historical figures mentioned in passing. However, El Paso, its restaurants, and its chefs and food writers, except for Carolyn, are real people who have kindly agreed to contribute their names, recipes, and establishments to this book, for which they have my profound thanks: Lionel Craver for his sangria recipe; Annette Lawrence, owner and chef at The Magic Pan for her recipe for Tlapeno/Tortilla Soup; Jose Nolasco of Desert Pearl for his Crab and Lobster Enchilada; Mr. and Mrs. Henry Jurado of Casa Jurado for their recipes for Enchiladas de Calebacitas and Pescado al Mojo de Ajo, and especially to W. Park and Norma Kerr for permission to reprint recipes for guacamole, Green Enchiladas, salpicon, and crepes with cajeta and pecans from their wonderful cookbook, The El Paso Chile Company’s Texas Border Cookbook.

Books I used for research in writing Holy Guacamole! are: Cleofas Calleros, El Paso’s Missions and Indians; Paul Horgan, Great River/The Rio Grande in North American History; W. Park Kerr and Norma Kerr, The El Paso Chile Company’s Texas Border Cookbook; Leon C. Metz, City at the Pass/An Illustrated History of El Paso; C. L. Sonnichsen, Pass of the North/Four Centuries on the Rio Grande; Reay Tannahill, Food in History; W. H. Timmons, El Paso/A Borderlands History; Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, translated by Anthea Bell, History of Food; James Trager, The Food Chronicle; and Alan Weisman, photographs by Jay Dusard, La Frontera/The United States Border with Mexico. NFH

Prologue

El Paso, Texas, the city to which my husband, Jason, and I moved several years ago, has always seemed an exotic place to me, but I’m adjusting. The city is beginning to feel like home. It’s not a small, dusty border town, as you might think if you’ve heard the Marty Robbins song. El Paso has over 700,000 people and Ciudad Juarez, across the river, over a million, maybe even two million. So many people from the interior of Mexico flood in yearly to work in the twin plants and to immigrate, not always legally, to the United States, that Juarez officials have no idea how many people live there.

El Paso has developed during the twentieth century into a city with tall buildings, a university, museums, a symphony, opera, and drama, but its history is Spanish, rather than English. Here at the intersection of Mexico, New Mexico, and Texas—a land of desert and mountains—the first Caucasians were Spanish conquistadors coming north from Mexico to look for land and riches and Spanish friars in search of new souls to convert.

We may now have a wide variety of restaurants, but the food we miss when we are away from home is Mexican food, the ingredients and recipes for which are descended from the Aztecs, Mayans, Incas, and North American Pueblo Indians. Our newspaper articles and conversation often circle around subjects such as the disappearing water supply, our stepchild status in our own state, and the third world diseases that come across the border or fester in our own colonias. We discuss the violence of the drug trade, which results in execution-style murders in Juarez and in El Paso because the cartels use our border to transport their product.

On the other hand, I feel quite safe here. El Paso has a low murder rate and an excellent record of catching killers and shipping them east for execution, Texas being a state that carries out a lot of executions, although less cruelly and more judicially than the rustler hangings of the old days. But violence is not new to El Paso. Our history is blood soaked, and our written history began in 1598 when Don Juan de Onate and his troops arrived at the Pass and claimed all the land drained by the Rio Grande for Phillip II of Spain.

Then he and his men continued north to found Santa Fe, and the El Paso area became, for two centuries of Spanish rule, the mid point for the caravans freighting supplies from Mexico City to northern New Mexico. The men and wagons took six months to reach Santa Fe, six months to distribute the goods, and six months to return to Mexico, and on the Camino Real, the route they took, they were always in danger of attack by Indians, particularly Comanches and Apaches. Las Cruces, only forty miles north of El Paso, is named after the crosses raised over the graves of those who died on the trail.

Mission Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe, which still stands in downtown Juarez, then named Paso del Norte, was founded in 1659 and completed in 1680, but it was the Pueblo Revolt in northern New Mexico ten years later that led to settlements here. The various tribes under their leader, Pope, rose on the same day and slaughtered Spanish colonists—men, women, and children. Unable to fight off the rebels, the Spanish governor, Don Antonio de Otermin, gathered those Spaniards who survived and those Indians who wished to come and fled down the Camino Real. These survivors settled in Paso del Norte, and at new missions, Ysleta, Socorro, and San Elizario, each built for different Indian tribes. Before the end of the century, the Spanish returned, took back the New Mexico colonies, and resumed the long journeys from Mexico City, through Paso del Norte, to Santa Fe.

Along the Rio Grande the settlers and Indians dug acequias for irrigation, built haciendas, raised herds of sheep, cattle, and goats, and crops of wheat, corn, chiles, melons, beans, European fruits, and especially grapes, from which they made wine. But even as trade grew and the land was cultivated from the eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, the Apaches rode out of the mountains and the Comanches from the plains to the east to raid and kill the Spanish and their Indian converts.

In 1821 Mexico fought for and won its independence from Spain, but life went on much as before, continuing the transformation from the European ways brought over by the settlers to the Pueblo ways of New Mexico and Mexico as Spain became a distant memory. And then the Anglo traders came and brought a new era of bloodshed after Texas won its war with Mexico and Alexander Doniphan’s Missouri Volunteers defeated the local Mexican army and took Paso del Norte in 1846. For a time the U.S. Army settled here to protect settlers and travelers from raiding Indians, who didn’t care what country claimed the land.

The Civil War, the local Salt War, the crime wave brought in by the arrival of the railroads, and the era of the gunslingers kept the blood flowing in the second half of the nineteenth century. Then the twentieth century turned El Pasoans into violence-voyeurs as the Mexican Revolution brought attacks on Juarez by Orozco, Pancho Villa, Huerta, and others. The shellings, dyamitings, and rifle charges played out across the river while our citizens watched from the top stories of buildings, railroad cars, and the river levees. There are photographs of ladies in white dresses with large hats and parasols and men in suits and hats enjoying the show, but some of the spectators were killed by stray bullets, and finally the U.S. Army returned in strength to pursue the bandit revolutionary Pancho Villa, no longer a hero in the United States. They never caught him.

Prohibition initiated another wave of crime and violence as liquor was smuggled across the river, and finally the drug wars began in the ’60s and ’70s and continue today, mostly across the river, but here in El Paso as well. Illegal immigrants, seeking a better life in the United States, drown in the river and die of heat, thirst, violence, and asphyxiation in the desert and in locked railroad cars and trucks.

We are a city with a long history of violence and death, which I had, heretofore, found a matter of interest rather than a cause for alarm. It didn’t occur to me that history could catch up with us, especially at a festive celebration after a production of Verdi’s Macbeth. We opera lovers enjoyed the hors d’oeuvres, the margaritas, and the cultural chitchat, but we also saw the beginning of a violent death.

The next day my amazing, cross-border adventure commenced—me: food columnist and faculty wife Carolyn Blue. But then, I’m getting used to adventure, just not at home.

It all began with the guacamole.

1

Après Macbetto

Carolyn

Jason and I were invited to join the Executive Committee of Opera at the Pass last spring, just before we went to France on a tour. They didn’t seem to care that we are so often away from home, all summer in New York, for instance, not to mention the various scientific meetings we attend because of Jason’s research on environmental toxins and our excursions for my syndicated food column “Have Fork, Will Travel.” My initial supposition was that the invitation stemmed from a desire to recruit someone for the committee to provide refreshments at parties and fund-raisers (little did they know that currently my interest lies more in eating than cooking).

Jason, however, served on a university committee with Vladislav Gubenko, the opera guru of the university music department and the artistic director of Opera at the Pass, which explained, according to Jason, why we were chosen, aside from our love of opera. It certainly wasn’t that we’re big donors, having given only a hundred dollars. After all, with two children in college and retirement staring us in the face twenty years or so from now, we try to be thrifty—well, Jason is thrifty, and he tries to keep an eye on me.

At any rate, we had attended a performance of Verdi’s Macbeth that Saturday night at the Abraham Chavez Theater, which is part of our local civic center, a rather impressive and very modern curved structure with five long, rounded windows deeply inset into thick walls. From the side, the building presents the appearance of crisscrossing slopes. Unfortunately, it has suffered from a leaky roof and other problems ever since it was finished in the 1970s. I myself have noticed stains on the curved wooden walls of the 2,500-seat theater, every seat of which was filled for Macbeth.

Instead of chandeliers, long curtains of crystals with lights behind them hang from the ceiling in the theater. Since I’d been reading EI Paso history, I couldn’t help but think of the much-admired chandeliers improvised for an all-night party at the home of trader James Magoffin in 1849—sardine tins attached to the hoops of pork barrels with lights attached. It must have been something to see. The historian even mentioned food served at the party—an imported “cold collation.” At most historic fiestas and banquets in El Paso history, much more notice was taken of the available beverages. For instance, when the Southern Pacific came to El Paso in 1881, historians tell us of speeches, cannons, a banquet, and a dozen bottles of champagne, seventeen gallons of wine, four hundred glasses of lemonade, and so forth. They must have had a good time, but did they get anything to eat? I knew, because I’d fixed some of the refreshments, that Macbeth was going to be celebrated with both food and alcohol.

And it was. Soon after the final bows, we attended the party with its gala postperformance crowd of singers, donors, members, and El Paso persons of importance. Dr. Peter Brockman, President of Opera at the Pass and wealthy neurosurgeon, gave a long-winded speech of thanks to those who had made the performance of Macbeth possible and promised that future productions would be less avant-garde. Obviously, he hadn’t cared for Vladik’s Tex-Mex version of Verdi’s tragic opera, in which the Scots had metamorphosed into contemporary drug dealers competing for control of the cocaine market, and the witches’ chorus was whittled down to three sopranos, further disappointing Verdi purists.

The artistic director actually interrupted the speech at one point to say that his production was calculated to bring in donors and ticket purchasers among Hispanics, who make up most of the city’s population. “University last year say I do zarzuela, no grand opera, or nobody buy tickets,” said Vladik, combing blonde locks away from a high forehead. “This year no money for any production at university. So Vladik save Opera at Pass from bankrupt.”

Dr. Brockman glared at him. Francisco (Frank) Escobar, member of the opera board and prominent community banker, who happened to be standing next to Vladik, said quietly, “On behalf of the Hispanic community, I’d like to say that we support grand opera and deplore drug dealing.” He is a slender, handsome man with ascetic features and silvering hair.

Vladik shrugged. “More Hispanic names on ticket list for Macbeth than last spring Abduction from Seraglio. I look.”

Dr. Brockman cleared his throat and introduced “our own opera-loving Father Rigoberto Flannery, who will lead us in prayer.”

Father Flannery, who had done a fine job singing Banquo but was now wearing his usual clerical collar and black suit instead of his rival drug-dealer costume (tight pants, alligator boots, unbuttoned silk shirt, and gold chain nestling on a hairy chest), took the microphone and beamed at the crowd. They in turn stopped eating hors d’oeuvres and drinking margaritas in order to join in prayer. I’d heard that Father Flannery is the son of a devout Hispanic mother from San Antonio and an alcoholic Irish father, who was killed while trying to escape family responsibilities by hopping a freight train to Houston. The Church had provided Father Flannery with schooling from boyhood on.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved