- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

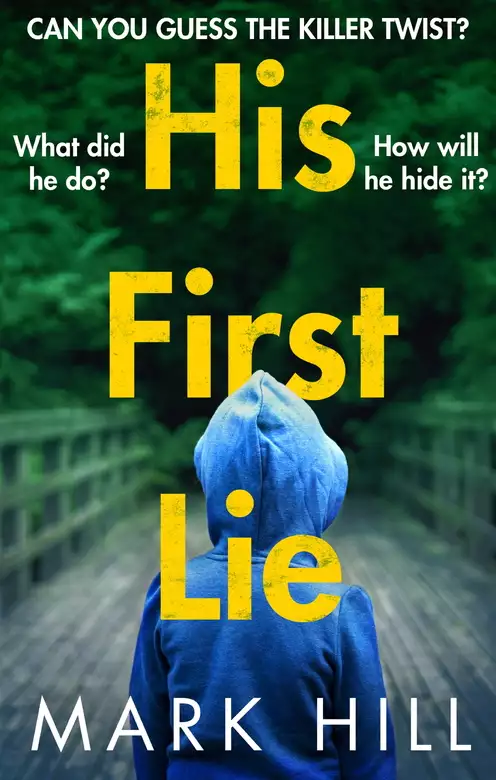

**THE GRIPPING THRILLER PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED AS TWO O'CLOCK BOY** 'A fantastic debut: dark, addictive and original. I couldn't put it down' Robert Bryndza, author of The Girl in the Ice Do you want a thriller that grips from the first line? Do you want a thriller to leave you gasping for air? Connor Laird frightens people: he's intense, he's fearless, and he seems to be willing to do anything to protect himself and those he loves. He arrives in the Longacre Children's Home seemingly from nowhere, and instantly becomes hero and villain to every other child there. Thirty years later, someone is killing all of those who grew up in the Longacre, one by one. Each of them has secrets, not least investigating cop DI Ray Drake. One by one the mysteries of the past are revealed as Drake finds himself in a race against time before the killer gets to him. Who is killing to hide their secret? And can YOU guess the ending? ' Grips from the start and never lets up' The Times ' Wreaks havoc with your assumptions. Hill has a hell of a career ahead of him' Alex Marwood, author of The Wicked Girls and The Darkest Secret ' A cracking debut. I can't wait to see more of Ray Drake.' Mark Billingham, #1 bestselling author of Love Like Blood and In The Dark 'Utterly gripping, packed with unforgettable characters - and SO well-written. The twists had me reeling!' Louise Voss

Release date: February 26, 2018

Publisher: Sphere

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

His First Lie

Mark Hill

The boy loved his parents more than anything on this Earth. And so he had to kill them.

Perched on the edge of the bunk, he listened to them now. To the squeak of their soles on the deck above as they threw recriminations back and forth in voices as vicious as the screeching seagulls wheeling in the sky. He heard the crack of the sail in the wind, the smack of the water against the hull inches from his head, a soothing, hypnotic rhythm.

Slap … slap … slap …

Before everything went wrong, before the boy went away as one person and came back as someone different, they had been full of gentle caresses and soft words for each other. But they argued all the time now, his parents – too stridently, loud enough for him to hear – and the quarrel was always about the same thing: what could be done about their unhappy son?

He understood that they wanted him to know how remorseful they were about what had happened. But their misery only made him feel worse. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d been able to speak to them, to utter a single word, and the longer he stayed silent the more his parents fought. The boy plugged his fingers into his ears, closed his eyes, and listened to the dull roar within him.

His love for them was untethering, drifting away on a fierce tide.

Slap … slap … slap …

A muffled voice. ‘Darling.’

The boy’s hands were pulled gently from his face. His mother crouched before him. Her eyes were rimmed red, and her hair was plastered to her face by sea spray, but she was still startlingly beautiful.

‘Why don’t you come up top?’

Her cold fingers tucked a loose strand of his hair behind his ear. For a brief moment he felt a familiar tenderness, wanted to clasp her to him and ignore the bitter thoughts that churned in his head. But he didn’t, he couldn’t. It had been weeks since he’d been able to speak.

A shadow fell across the hatch. His father’s voice boomed, ‘Is he coming up?’

‘Please, let me handle this,’ his mother barked over her shoulder, and after a moment of hesitation, the shadow disappeared.

‘We’re doing the best we can.’ She waited for her son to speak. ‘But you must tell us how you feel, so that we can help you.’

The boy managed a small nod, and hope flickered in his mother’s gaze.

‘Your father and I … we love you more than anything. If we argue it’s because we can never forgive ourselves for what happened to you. You know that, don’t you?’

Her eyes filled with tears, and he would do anything to stop her from crying. In a cracked voice, barely more than a whisper, he heard himself say, ‘I love you.’

His mother’s hand flew to her mouth. She stood, hunched in the cabin.

‘We’re about to eat sandwiches.’ Moving to the steps, she spoke brightly, but her voice trembled. ‘Why don’t you come up when you’re ready?’

He nodded. With a last, eager smile, his mother climbed to the hatch and her body was consumed by sunlight.

The boy’s heel thudded against the clasp of the toolbox beneath his berth. He pulled out the metal box and tipped open the lid to reveal his father’s tools. Rasps, pliers, a spirit level. Tacks and nails, a chisel slick with grease. Lifting the top tray, the heavier tools were revealed: a saw, a screwdriver, a peen hammer. The varnish on the handle of the hammer was worn away. The wood was rough, its mottled head pounded to a dull grey. He lifted it, felt its weight in his palm.

Clenching the hammer in his fist, he stooped beneath the bulkhead – in the last couple of years he’d grown so much taller – to listen to the clink of plastic plates, his parents’ animated voices on the deck.

‘Sandwiches are ready!’ called his mother.

Every night he had the same dream, like a terrible premonition: his parents passed him on the street without a glance, as if they were total strangers. Sooner or later, he knew, this nightmare would become a reality. The resentment they felt that their child had gone for ever, replaced by somebody else, someone ugly inside, would chip away at their love for him. Until there was nothing left.

And he was afraid that his own fierce love for them was slowly rotting, corroded by blame and bitterness. One day, when it was gone completely, other emotions would fill the desolate space inside him. Fury, rage. A cold, implacable hatred. Already he felt anger swelling like a storm where his love had been. He couldn’t bear to hate them, yearned to keep his love for his parents – and his memories of a happy time before he went to that place – uncorrupted, and to carry it with him into an uncertain future.

And so he had to act.

Gripping the hammer, the boy moved towards the hatch. His view filled with the blinding grey of the sky and the blur of the wheeling gulls, which screamed a warning to him that this world would always snatch from him the things he cherished, that life would always be this way.

He stepped onto the windblown deck in the middle of a sea that went on for ever.

Slap … slap … slap …

Present day

Everybody wanted a piece of Detective Inspector Ray Drake.

He circled the room, accepting handshakes and backslaps until there was no one left to congratulate him. Soon, he hoped, they’d all get too drunk to remember he was there and he’d be able to slip away.

He was being selfish, he knew that, but large social gatherings like this made him uncomfortable, particularly when he was in the spotlight. If she were here, Laura would tell him to leave right away, not to worry about what anybody else thought.

Detective Constable Eddie Upson was already well on the way to getting pissed. Waving his pint around, he cornered Drake to moan about missing out on promotion.

‘It’s not like I haven’t delivered.’ Lager slopped belligerently over the lip of his pint. ‘You know what I can do.’

‘Excuse me a moment, Eddie.’

At the back of the room, clinging to the wall beneath a curled poster of Jimmy Greaves, was Flick Crowley, the only person who looked like she wanted to be in this pub less than he did, and Drake pushed towards her. On his way, he elbowed Frank Wanderly.

‘Sorry, Frank.’

‘That’s quite all right.’ The duty sergeant clasped his hands together. Tall and gaunt, and with not a single hair on his head, everybody at the nick fondly called him Nosferatu. ‘And congratulations once again, DI Drake, it’s well deserved.’

A few hours earlier, Drake and his Murder Investigation Team had received a Commendation for outstanding service, commitment and teamwork, after the successful completion of a series of homicide investigations in Haringey. Cops and civilian staff had come from Tottenham Police Station to celebrate beneath a blizzard of Spurs memorabilia – shirts, scarves and photos – on the walls.

Drake smiled his thanks, and kept moving.

‘You’re looking smart tonight, guv,’ Flick said.

Drake was wearing the same clothes he always did, a dark off-the-peg suit, white shirt and a frayed brown tie – which Laura had bought him many years ago and lately he’d taken to wearing again – so he guessed she was being mischievous. He was a restless, wiry man who found it impossible to stop moving for long, and no oil painting either. Drake’s craggy face was all unexpected drops and sharp angles, as if carelessly hacked from stone.

‘I spoke to Harris earlier.’ He placed his glass of orange juice on the ledge against the wall, glad to be shot of it. ‘Told him how glad I was that you got the promotion.’

Flick frowned. ‘As if you had nothing to do with it.’

Detective Chief Inspector Harris had been adamant that they should bring an experienced pair of hands into the Murder Investigation Team, but Ray Drake had gone to war on Flick’s behalf, and she’d been promoted from Detective Constable to Detective Sergeant. He had worked to build her confidence, to make her believe in herself a bit more. She was prone to hide behind procedures and systems, but fundamentally she was a fine copper. In time, when she’d learned more readily to trust her instincts, she’d be a very good detective indeed.

‘If anyone deserves the chance, it’s you.’

Flick glanced over at Upson, his arms draped over the shoulders of the two young PCs he’d clearly singled out to be his drinking comrades for the evening, regardless of their feelings on the matter. ‘Eddie doesn’t seem to think so.’

‘He’ll come round. I want you to lead the next investigation, whenever it comes in.’

‘Really?’ she asked, surprised.

‘I think you’re ready, DS Crowley.’

She took a gulp of wine, not knowing what to say. ‘I meant to ask, how’s April?’

‘Good.’ Drake stiffened at the mention of his daughter’s name. Things hadn’t been good between them, not since the funeral, and he hadn’t the slightest idea how to make things better. ‘She’s good.’

‘The offer still stands. If you’d like me to talk to her …’

‘Thank you.’ He nodded at Harris. ‘The DCI has brought along a couple of suits from Scotland Yard.’

‘I didn’t mean to—’

‘Come on,’ he said quickly, ‘I’ll introduce you.’

‘You know what? I think I’ll give it a miss.’ She drained her glass of red. ‘Besides, it looks like Vix has got that area locked down.’

Detective Constable Vix Moore was working the guys from the Yard, nodding gravely, the tips of her long blonde bob bouncing, as they explained the latest Met reorganisation proposals.

‘Besides,’ said Flick, ‘I’m shattered, and I want to get home.’

‘Stay a while longer. We’re celebrating your good news, as well.’

‘To be honest, it’s been a crazy couple of months – work’s been non-stop – and I fancy an early night.’ Drake wondered if there was something else on her mind. Flick’s watchful almond eyes gave little away beneath a thick fringe of brown hair. A tall woman, a shade below six foot, she had a tendency to hunch, as if the weight of the world was bearing down on her shoulders. She had been a keen swimmer once upon a time, and a good one, she had told Drake. The top of her arms tapered into a strong, lean body, but her broad shoulders rolled forward apologetically. ‘Sorry, guv, but I don’t think I could bear it if someone says a few words.’

‘Fair enough.’ Having heard more than one of Harris’s interminable speeches, he couldn’t blame her. ‘But just for the record, I’m proud of you.’

‘Thank you.’ A hesitant smile played across her face. ‘I really appreciate everything you’ve done.’

Her last words were clipped by the sound of a pen ringing loudly against a glass.

‘Attention, everybody!’ DCI Harris’s stomach strained against a tight Lycra top, and his shins were pale beneath lurid black and yellow cycling shorts.

‘Too late,’ Drake whispered as conversation died and a respectful space opened around him and Flick.

‘I know everyone’s having fun, however I really wanted to say a few words about the very deserved commendation given to DI Drake and his team,’ said Harris. ‘But first, we’ve a new detective sergeant in our midst, so I want you all to put your hands together for Flick Crowley.’

‘Smile for the ladies and gentlemen, DS Crowley,’ murmured Drake, behind the grin bolted to his face.

Hanging onto her empty glass, Flick shot him a look that suggested, on balance, she’d rather face a firing squad.

Kenny hated going straight. Loathed it.

He’d been a good boy for three years now – three years, eight months and fourteen days, to be exact – and every single minute of every single hour had been excruciating. A few years back, if you’d told him that he’d be strapped onto the dreary treadmill of so-called everyday life, he’d have laughed in your face. Now the joke was on him, having to work nights in a supermarket, stacking shelves and lugging pallets beneath pallid yellow lights that exaggerated every pimple and line on your face.

The night bus groaned away down Tottenham High Road, carrying off the motley collection of night owls who sat obscured like phantoms behind glass thick with condensation, and within minutes Kenny was striding down Scales Road, past the foxes nosing around the bins, to let himself into his little terraced house.

Tonight he’d had another row with his supervisor, a spotty kid with a business degree. He picked fights with Kenny every chance he got just to show who was in charge, stomping up and down the aisles, clip-on tie swinging like a limp dick. Stack those boxes, tidy that display!

On top of that, Kenny had lost his mobile. God knows where. He knew he’d had it when he left home, but when he’d gone to put it in his locker it had disappeared.

A floorboard creaked above him, and he spotted Phil’s bag nudged beneath the stairs. That girlfriend of his had likely thrown him out again and he was sleeping in the spare room. Kenny loved his sons, honestly he did, but Phil’s snore was as loud as a steam train.

He took a glass from a kitchen cabinet and poured a measure of Bell’s. This was his nightly ritual, the one part of his day he looked forward to: a modest snifter before bed.

After the first sip the familiar debate began in his head.

He’d been given a second chance, and for that he was grateful. But he missed his old life. This was the truth that always returned in the early hours. He yearned for the thrill of living on the edge. Time was, every decision had consequences. Kenny woke in the morning not knowing how he’d get his hands on money to feed his family, or whether the cops would come knocking. He could be packing a bag for prison or heading out on a five-day bender. Each and every day was different; Kenny had felt alive.

Now he was a worker ant, toiling in the early hours alongside students and ethnics. The plan was to buy a cab. He worked nights, slept mornings and went out on his moped in the afternoons to learn The Knowledge. Babs was learning it, too. At weekends they tested each other about roads, cul-de-sacs and byways. In a couple of years they’d have enough in the bank to buy a Hackney Cab. They’d watched a documentary about a cabbie who’d earned so much money he’d bought himself a plot of land on the Costa, a little piece of paradise, complete with a pool and an orchard. That was their dream, their destination. All he had to do was keep turning up for work. It wouldn’t be for ever.

Because for reasons he didn’t want to examine too carefully, Kenny was desperate to move away.

As far as he could.

That old uneasiness settled on him. His thoughts drifted to those people from the home. It didn’t seem possible they were all dead. But it was Jason’s death that really got to him. Jason, who’d gone crazy with the stress and strain of it, so they said, and put a shooter to the heads of his nearest and dearest. Jason was a mad sod, everyone knew that, but nobody would convince Kenny that Jason killed his girl and kid and then blew his own brains out.

He drained the glass and placed it in the sink. Blobs of rain pattered across the window. The back door rattled. Checking the handle, he found it unlocked. That was Babs, in and out of the garden all night, smoking, littering the plant pots with fag butts. He turned the key in the door and wearily climbed the stairs.

Kenny took a piss, careful not to splash the seat, and shuffled down the hallway. Christ, it was pitch black. The door to the spare bedroom was open, the room empty. Phil must have changed his mind about staying – or more likely he was still out with mates.

A pungent stink hit him as soon as Kenny opened the door to his bedroom – Babs’s muggy exhalations. Kenny loved that smell. He was seconds away from snuggling against her.

But there was another smell he couldn’t place – chemical, plastic.

His wife cried out – a toneless, muffled sound.

‘Sorry, love.’ Kenny stumbled out of his trousers, trying not to disturb her. The stench in his nostrils was bitter, acrid. ‘Bloody stinks in here.’

The soles of his socks felt damp. He dabbed anxiously against the wall to find the light switch.

And when he turned it on, when he saw, he knew he was lost.

His head was yanked back and a cold blade placed against the loose skin at his throat.

A voice hissed in his ear: ‘Hello, Kenny. Long time no see.’

Ray Drake walked anxiously towards the crime scene. He was there within minutes; it was barely a few hundred yards from Tottenham Police Station.

Police vans and squad cars were parked along the street. Clots of people gathered in the sweep of the cherry lights to watch the proceedings from the outer cordon. An inner cordon sealed off the middle of the street to all but scene-of-crime officers and authorised personnel. Drake badged the uniform there, and took a pair of polythene shoe-covers from a bag dangling from his clipboard.

Eddie Upson stood on the pavement, making the bins look untidy. His eyes were bloodshot, and his shirt flapped open at the bottom to reveal a wiry tangle of stomach hair. When Drake left the pub last night – after that speech by Harris finally ended – Upson looked settled in for a long session.

‘Upstairs, sir.’

Drake nodded up at the bedroom. ‘What’s it like?’

‘Not pleasant.’ Upson smothered a yawn. ‘It’s kind of … intense.’

‘We keeping you up, Eddie?’

‘Bit of a headache.’ Upson stretched. ‘Thought you’d leave all the crime-scene malarkey to Flick – uh, DS Crowley – now.’

Upson discreetly tucked in his shirt as they walked up the path to the house. Drake knew he shouldn’t be there, Flick was the officer in charge and he should just let her get on with it, but Harris would be all over this investigation like a rash. A triple murder just around the corner from a police station – the media would have a field day.

That’s what he told himself. But there was something else.

When he was given the name and address of the possible victims, an alarm, a warning signal buried deep inside of him, had gone off, spluttered into life like a candle, dormant for decades, igniting in the depths of a bottomless cave.

He had to be there. He needed to be there.

‘Talk me through it,’ he said.

At the door, they slipped the elasticated bootees onto their shoes, Eddie swaying dangerously as he lifted one leg and then the other.

‘The house is rented by a middle-aged couple called Kenny and Barbara Overton.’

‘We’re sure it’s them?’

‘Neighbours ID’d their DVLA photos.’

‘And the third victim?’

‘Kenny and Barbara have two grown-up sons who’re always popping in. Phillip and, uh …’ He squinted at his notebook. ‘Ryan.’

‘Which one is it?’

‘We don’t know yet. They’re twins – but not identical. Cars are on the way to both addresses.’

They stepped aside to let a pair of scene-of-crime officers carry tubs of equipment into the house. Drake took nitrile gloves from his pocket and shook them out, taking his time about it. There was a faint tremor in his hands when he snapped them over his wrists.

‘Coming inside, guv?’

Upson had an expectant look on his face. Drake wondered how long he’d been standing there fiddling with the gloves, unconsciously putting off the moment when he had to step inside …

On the landing a large battery-powered arc light was stooped towards the doorway of the front bedroom, its white beam switched off. The bodies inside that room could stay there all day and long into the night, as the CSIs painstakingly recorded the crime scene and a pathologist studied them in situ.

From the room came the whir of a camera. Every detail of the crime scene would be photographed hundreds of times and the images added to an evidence database.

Drake ducked beneath the lamp, stepping carefully across the tread plates that allowed everyone to move around without contaminating evidence on the floor. A crime scene could become a crowded place, with crime scene examiners, coppers, pathologists and medical staff trampling everywhere. On the other side of the room, Flick Crowley frowned at the bodies.

‘Who found them?’

‘A neighbour gets up early every morning,’ said Flick. ‘He’s out of the house by five thirty, works in the kitchen of a West End hotel. He walks past, sees the front door is wide open. Thinks it’s a burglary, so he goes inside to take a look around. Seconds later, he comes out screaming. Runs into a pair of Specials scoffing burgers on the High Road. They come back, call the paramedics and close off the scene.’

‘And nobody else saw or heard anything?’

‘The neighbour on the left is a young mum. She was up at three a.m. breastfeeding. Said she heard a shout.’

‘A shout?’

‘A noise, a cry, she couldn’t be sure.’ Flick pressed against the wall to let the forensics guy leave. ‘She didn’t think anything of it. Mr and Mrs Overton love a good row, apparently.’

Turned inwards to face each other, the three victims were trussed to kitchen chairs by layer upon layer of plastic film, from toes to nostrils. Their arms were formless lumps pinned to their sides.

The wrapping glinted blue in the stark morning light, except across their torsos, which were slashed and shredded and dripping red. Serrated flesh and chunks of gristle poked from jagged holes in their chests and stomachs. Smooth piping and ruptured veins and organs glistened vividly against glimpses of white ribcage. The gouges were deep and wide and, Drake guessed, made by a long, flat blade. He leaned closer to get a better sense of depth. The fleshy bottom lips of the wounds were angled sharply downwards, like fish mouths.

Their killer had stood over them and brought the knife down again and again. Were they awake, these poor people, Drake wondered, and forced to watch the deaths of their loved ones, knowing they would be next? Were they killed one after the other, in a particular order? Or did the killer stab at them randomly, whirling wildly from one victim to another, until the slaughter was complete?

A sliced arterial vein could spurt blood a good few feet into the air. Spatters of it flecked the walls, the net curtains, the delicate china figurines on the window ledge. The duvet on the bed was soaked, the rug beneath the victims’ chairs sodden black. Blood bubbled at the base of the tread plates as Drake stepped across them.

There was a riot of partial footprints in the sticky liquid, left by the special constables who discovered the grisly scene and the paramedics who searched futilely for any faint pulse. Maybe, just maybe, the perpetrator’s prints would be among them.

There was no sign of a blade. The killer may have dropped it in panic, in the house or surrounding streets. It could even be lying on the steps of the station round the corner. That would go down well in the press.

‘No weapon’s been found,’ said Flick, as if reading his mind. ‘We’re hoping to get enough bodies together for a search within twenty minutes. Millie Steiner’s on it now.’

A systematic search was difficult at the best of times, let alone in the crowded inner-city streets. The surrounding area was a dense maze. Parts of the High Road would have to be closed off before the rush of Saturday-morning shoppers made the task of finding the weapon all but impossible.

‘The King is dead,’ intoned a voice behind Drake. ‘Long live the King!’ Peter Holloway, the crime scene manager, stood in the doorway. ‘Just can’t keep away, can you, DI Drake?’

‘What else am I going to do on a weekend?’

‘Practise that golf swing,’ he said. ‘Or take that lovely daughter of yours somewhere special.’

‘I’d rather come and interfere with your crime scene, Peter,’ said Drake. ‘For old time’s sake.’

‘My people need to get on,’ said Holloway.

‘We won’t be long,’ said Flick.

Holloway was right, of course. His team needed to go about their business. Logging and recording. Videoing, photographing, removing evidence for examination. As CSM, Holloway’s job was to coordinate the collection of evidence and protect the integrity of the forensic investigation. Ray Drake always liked to get to the crime scene as soon as possible. The first few hours of any investigation – the so-called Golden Hour – were the most critical, and he and Holloway often exchanged forthright views if the CSM felt he was getting in the way.

Drake had a grudging admiration for the bombastic know-all. A lean, middle-aged man, there was a vanity to his precise movements. When Holloway pulled down the hood of his coveralls, his face was taut and unblemished. Drake often wondered if he’d had some discreet work done.

‘You’ve very big boots to fill, DS Crowley.’ A pair of half-moon glasses tipped from his hair onto his nose with a jerk of his head.

‘If I didn’t know it already,’ said Flick, who was looking at the windowsill, ‘there’s a plenty of people to remind me.’

Holloway gestured with his clipboard. ‘You’ll never be the investigator that DI Drake is.’

‘Thanks,’ Flick said quietly. ‘I’ll try to remember that.’

‘No need to be so touchy, DS Crowley. What I mean is, be your own person, do things your own way. If you try to be a mere simulacrum of Ray Drake, you’ll fail.’

‘I’ve no idea what a simulacrum is, but thank you anyway.’

‘She’ll go far, this one,’ said Holloway, nodding at her.

Drake didn’t look up from the bodies. ‘Yes, she will.’

‘One’s missing,’ said Flick.

‘Excuse me?’

‘The figurines.’ She pointed at three porcelain eighteenth-century figures – a woman in a gown and bonnet, men in waistcoats and three-cornered hats – spaced irregularly on the sill. ‘There’s a space where one’s missing.’

‘Smashed, maybe,’ said Drake.

‘Guv …?’ Vix Moore’s head peeked from behind the banister on the landing, her gaze moving quickly from Drake to Flick. ‘I mean, guv …’

‘What is it, Vix?’

‘Someone’s just turned up at the cordon. Says he’s Ryan Overton.’

‘I’ll come down.’ Hesitating in the doorway, Flick looked at the cocooned victims one last time. ‘They’re like human flies ensnared by a giant spider.’

Holloway followed her to the door. ‘I was thinking more along the lines of mouldy wrapped sandwiches at a seaside café.’ He turned to Drake. ‘Make it quick, please.’

Left alone in the room, Drake forced down the nausea he felt. The stench in the room, of plastic and plasma, was overpowering as he moved from one body to another.

The younger man – in all likelihood Phillip Overton – sat with his head thrown back like a schoolboy laughing at the back of the class, a tight ruffle of plastic shredded around his mouth. His blank eyes were open, and his scalp was sprayed with inky globules of blood.

Barbara Overton’s head, partly concealed by the sheets of plastic cut away by the paramedics, lolled on her chest. Her hair, matted with blood and gristle, was pulled back in a lank ponytail, her slack face imprinted with traces of the terror of her final catastrophic moments on Earth.

Drake arrived at Kenny Overton. The tops of his thighs burned when he crouched to get an eye-level view of the dead man’s face. Wisps of fine auburn hair congealed against Kenny’s scalp. His jowls flopped over the moist plastic around his neck, and his gaping mouth revealed crooked teeth and withered gums stained by vomit and blood.

Horrific death aside, time had not been kind to Kenny Overton.

That sense of foreboding tightened in Drake’s stomach. His hand shook when he lifted it. Something hidden, something dangerous and wrong, had been revealed.

A countdown, a slow, inexorable pulse in his gut.

‘Kenny,’ he whispered. ‘It’s you.’

1984

Ray Drake first met Connor Laird on the hot summer day when Sally Raynor found the new kid at Hackney Wick Police Station.

‘Fucking hippy,’ an officer muttered as he lifted the wooden counter to allow Sally into the warren of corridors behind the front desk. She swept past in a heavy poncho and long woollen skirt. A battered satchel, its straps curled and frayed, bumped on her hips.

Sergeant Harry Crowley’s office was barely larger than a broom cupboard, just big enough to squeeze in Harry and a desk heaped with a mountain of paperwork. The heat hit Sally like a hammer when she walked in, the office was right above the station’s boiler. Harry knew where all the bodies were buried in this place, and Sally suspected that someone was trying to sweat him out of the building.

A kid, no older than fourteen or fifteen, was perched on a stool in front of Harry’s desk, and she asked, ‘Who have you got here?’

Harry scratched his belly. ‘A tough guy.’

A fan burred at the edge of his desk, lifting a coil of Brylcreemed hair from Harry’s forehead. He looked like Tommy Cooper, that funny magician on the telly, and some joker had given him a red fez, which was forced over the top of a framed photograph of his wife and children.

Harry reached into his tunic to take out a packet of cigarettes, stuck one in the corner of his mouth.

‘What’s your name?’ Sally crouched in front of the boy. A thick helmet of dark hair framed the kid’s dirty face, his mouth was an angry smear. ‘Where have you come from?’

‘Don’t waste your breath. He ain’t one for talking.’ Harry blew out smoke. ‘One of my lads found him wandering the streets this afternoon. Dennis knocked his helmet off.’

‘Dennis? That’s his name?’

‘That’s what I call him – Dennis the fucking Menace.’ H

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...