- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

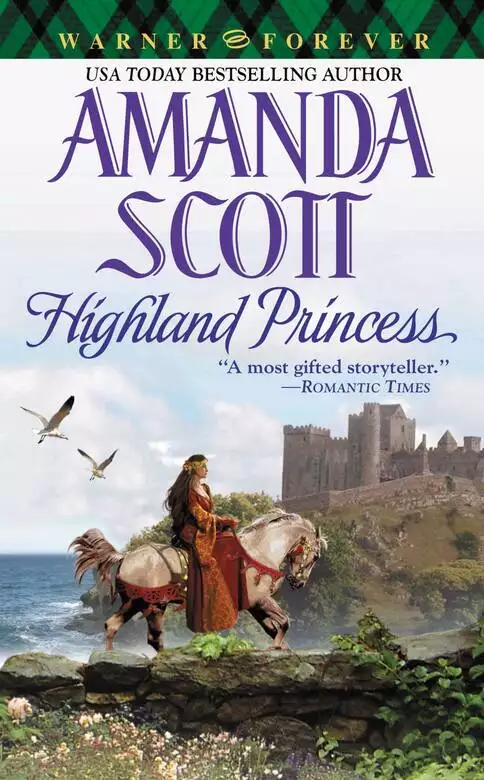

Lady Mairi Macdonald, daughter of the Lord of the Isles, and blessed in ways other women of her time never even dream of, is the kingdom's most sought-after bride. But no man has touched her heart, least of all the prince everyone expects her to wed. Then Lachlan "The Wily" Maclean, a Highland warrior with a network of spies that keeps him the most well-informed man in the kingdom, joins the Court of the Isles. He passionately wants Mairi, and although she scorns his impudent ways, she gasps at his touch . . . Accustomed to fighting for what he wants, Lachlan forms a daring plan to win her, only to ignite the jealousy of a powerful, implacable enemy who expects to win not only Mairi but the entire Kingdom of the Isles.

Release date: November 15, 2008

Publisher: Forever

Print pages: 404

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Highland Princess

Amanda Scott

Loch Gruinart, the Isle of Isla, Scotland, March 1366

The tide was going out, and still he had not come to her, despite his promise to arrive at the loch early so that she could get home before dark. Already she was late starting, and it would be as much as her life was worth if she failed again to have supper ready on time.

She walked along the sand toward the cliffs on the north shore, determined not to look as if she were impatient for him. As always, a thrill rippled through her at the thought of the danger in what she did. She liked a bit of risk, though. It added interest to her otherwise humdrum existence.

He had said he had to go to Kilchoman and would meet her on his way back, so he would come soon. He had to come. He had to take care of her, too, and the bairn, because he had promised he would. He was not always able to keep his promises, but he had to keep this one. He had to make her feel safe again.

As the sun sank nearer the horizon, she stood staring at the sea, forcing herself to relax, to enjoy the changing patterns of light. The dull gray clouds drifting overhead would turn to brilliant, rosy colors as the sun set, although she dared not linger long enough to see it, and the sight would not be as splendid from home.

A twig snapped, and she whirled with a smile of welcome that vanished when the man she saw was not the one she expected.

“You!”

“Aye, ’tis me, right enough,” he snarled, striding up to her and putting both hands on her shoulders, gripping so tightly that she cried out.

“Don’t! Let me go!”

“Nay, then, ye were warned no t’ play off more o’ your tricks, lass. Ye’ve done it now for the last time, I’m thinking, if ye ken what’s good for ye. But afore I teach ye t’ mind your betters, ye’ll be paying a wee tribute, as his grace might say.”

She screamed, but no one heard her except the one collecting his tribute, and her screaming was no more to him than the gulls’ shrieks overhead. Indeed, it added spice for him to know she was paying dearly now for the wrongs she had done him in the past.

Although she did not know it then, she had already seen her last sunset.

Before long, her screams faded to silence.

Chapter 1

Near the eastern coast of Isla, a fortnight later

Dense fog blanketed the sea, flattening the waves and creating a world of eerie silence where water, land, and sky merged into impenetrable grayness. That fog was stealing the last hours of Ian Burk’s life.

Each passing minute drew the hangman’s noose nearer, but without wind, the slender royal galley bearing his hopeful rescuer could only drift with the tide. Its great square sail was useless and its eighteen oarsmen, unable to judge their exact location or course, had long since stopped rowing. They and their three passengers sat in silence as thick and heavy as the fog-muffled surroundings, listening intently.

Seventeen-year-old Lady Mairi of Isla pulled her hooded, fur-lined crimson cloak more snugly around her, stifling impatience. Even her father, the most powerful man in the Isles if not in all Scotland, could not successfully order fog to dissipate.

Beside her, her woman Meg Raith muttered, “’Tis cruel o’ the fog t’ blind us after the stars and wind we had when we left Dunyvaig. In troth, one canna help but wonder now what lies beneath us.” Her voice shook on the words.

“No sea monster stalks these waters,” Mairi said firmly.

“None would dare,” Meg agreed as if no thought of monsters gliding through the dark depths below had ever entered her head. Less resolutely, she added, “Be ye certain, mistress?”

“Aye, and in any event, the sun is up or soon will be, because everything around us was black a short while ago,” Mairi said, pushing a damp, dark curl back under the shelter of her hood. “Moreover, Meg, it is the very nature of fog to creep up on unsuspecting travelers. This one would not seem nearly so eerie had it not swallowed us in the darkness before we realized it was so near.”

“Mayhap ye be right, mistress, but ’tis unsettling all the same.”

Mairi agreed. Highland galleys usually moved swiftly, especially when wind and tide were favorable, and she loved the sea. The journey from her father’s castle Dunyvaig, on the southeastern coast of Isla, to his administrative center on Loch Finlaggan in the north was nearly always a safe one and—at just over twenty miles—relatively short. But even the longest journeys on the water were seldom boring, because the scenery changed constantly and playful otters or seals often accompanied the galleys, amusing passengers with their antics.

She had rarely made any journey on a moonless night, however, with only stars to guide her helmsman, and now, thanks to the fog, the trip had taken hours longer than usual. And hours, for Ian, were precious.

Just then, the helmsman blew two notes on his ram’s horn, as he did at ten-minute intervals, both to give warning of their presence to anyone else daft enough to be on the water in such murk and to demand a response from the lookout at Claig Castle when they drifted near enough. The massive fort on the Heather Isle guarded the south entrance to the Sound of Isla, a waterway of great strategic value to Mairi’s father, MacDonald, Lord of the Isles and King of the Hebrides.

She turned her attention to the galley’s stern, where her fair-bearded half brother lounged on a pile of leather skins beside the helmsman, looking grimly annoyed through the thick mist that billowed about him.

Knowing her voice would carry easily in the silence, she said quietly, “How much farther do you reckon it is, Ranald?”

His expression softened as he shifted his gaze to her. Like all three of her elder half brothers, twenty-one-year-old Ranald was a large, broad-shouldered, handsome man who bore the natural air of authority that sat easily on each of them. A little smile touched his lips as he said, “Near, lass, but not so near that I can promise ye’ll be warming your toes by a fire in less than an hour or two.”

“The water seems so still,” she said. “I can scarcely tell if it is the fog or the boat that moves. Has the tide begun its turn?”

“Nay,” he said. “It still carries us northward, and I warrant we’ll reach the Sound’s entrance soon. Doubtless the men at Claig hear our horn already, but fog distorts noises on the water, and they’ll want to be certain of us afore they answer.”

She nodded. Like anyone who had grown up with the sea as a constant companion, she understood its moods and movements well enough to know she would feel a distinct difference when they met the swifter flow of the tide through the narrow Sound. As for the helmsman’s horn, not only was it the duty of the men at Claig Castle to respond to it but also to collect tribute from those permitted by the Lord of the Isles, rather than by birthright, to take the shorter passage through the Sound. The Claig watchmen would therefore be paying close heed.

But time passed so quickly that minutes now seemed like heartbeats.

Her thoughts returned thus abruptly to the subject that had occupied them since the previous night, when she had learned of Ian Burk’s peril upon Ranald’s return to Dunyvaig from Knapdale. He had been away two days, leaving her in charge of the castle, although her responsibility was light, since the castle’s captain was one of MacDonald’s most capable men.

The Lord of the Isles believed, however, that his offspring should know as much about what kept his castles and Lordship running smoothly as the people who did the work, and Dunyvaig was one of his most important holdings. It served both as guardian of the sea-lanes to the south and as safe harbor for his galleys, birlinns, and larger ships of war. From the castle’s high, cliff-top site, its view encompassed much of the Kintyre coast and a vast panorama of the sea to the south. The harbor below, in Lagavulin Bay, was hidden from passersby and well fortified.

Ranald’s present duty at Dunyvaig was to oversee the careening of MacDonald’s ships, a chore done twice a year when scores of men rolled each ship ashore over logs so that they could scrape its bottom clean of barnacles.

This was the second year Mairi had accompanied him to Dunyvaig, entrusted with seeing to its household, to make sure the larders were full and that all was in good repair. For, as competent as the castle’s captain was, he was yet unmarried, and therefore her mother, the lady Margaret, had formed the habit of looking in on Dunyvaig at least once a year to see that all was in order. That duty having devolved upon Mairi, she had acquitted herself well the previous year and had returned confidently a month before to do so again.

Thus, when Ranald had said MacDonald desired him to invite a new Knapdale chief to attend the annual Council of the Isles that week at Finlaggan, she had not turned a hair at learning she would be alone overnight among a household of men-at-arms with only her maidservant for protection. No man loyal to her father would harm her or Meg, and few men were more loyal than those at Dunyvaig.

The family would remain at Finlaggan for only a fortnight after the Council adjourned, because they would spend Easter as usual at Ardtornish, MacDonald’s favorite seat, fifty miles to the north on the Morvern coast of the Sound of Mull. In midsummer, they would return to Isla so Lady Margaret could take the children to Kilchoman, their summer residence. It was a splendid palace, built only two years before on the west coast of Isla, but it was no place to be in a howling spring storm. Ardtornish, better protected against the winds, was infinitely preferable.

In any event, no household as large as theirs could occupy any residence for long. The demands made on the garderobes, not to mention stores and cellars, made it essential to move about frequently if only to let the servants attend to the cleaning in peace without having to deal with constant demands of family members.

Lady Margaret had sent word to Dunyvaig with Ian Burk a fortnight before, reminding Mairi and Ranald that his grace expected them to have completed their duties there by the time his Council adjourned, because they would both need time to prepare for departure to the north.

That her duties at Dunyvaig would mean missing the Council of the Isles had not distressed her, for although a few men sometimes brought family members, most waited until his grace moved north before bringing wives and marriageable sons and daughters to attend his court. Not only was Ardtornish more centrally located, but everyone was eager to take part in his Easter tinchal, the grand deer hunt that had begun to provide fresh venison for the Easter feast at Ardtornish and had soon grown into an annual social event.

No sooner did she greet Ranald’s return to Dunyvaig, however, than she saw from his expression that something was wrong and demanded to know what it was.

“We met one of his grace’s birlinns on its way to Loch Tarbert,” he said. “They said that most of the councilors have arrived at Finlaggan, and he means to begin the court of grievances tomorrow, and . . . well . . .”

“And what?” she asked bluntly when he avoided her gaze.

“You won’t want to hear it, lass,” he warned her, adding reluctantly, “’Tis gey possible that his grace will hang Ian Burk.”

“Ian?” Her senses tilted, and a sickening chill swept over her. “But how can he?” she demanded. “Ian is infinitely trustworthy, Ranald. Why, he has looked after my ponies from my childhood—aye, and me, too! What can he possibly have done to warrant hanging?”

“The charge is murder, Mairi, and though I ken fine that you’ll be wanting to return to Finlaggan straightaway, we can do naught to prevent his hanging if his accusers prove their charge. Under our Brehon laws—”

“I know our laws, Ranald, but his accusers must be daft. Who was killed?”

“Elma MacCoun,” he said. “They say Ian pushed her off a cliff.”

“That cannot be so! I tell you, Ranald, Ian has no violence in him.”

He did not argue but neither could he placate her. She dismissed his attempts, saying flatly, “We have no time to lose.”

He said calmly, “We can scarcely go this minute, lass.”

“Mayhap we cannot, but we must go as soon as you can order a galley prepared and we pack our things.”

“Tomorrow at dawn will be soon enough,” he said. “There will be a host of grievances to hear, because there always are. Moreover, the men I met said only that most of the councilors had arrived, not all.”

“But that was yesterday, was it not?” When he nodded, she said, “And his grace does not need any of them to hold his trial, sir, as well you know. Moreover, we cannot turn back the hours, and if we spend too many, Ian will suffer their waste through eternity. I mean to prevent that, Ranald, so do make haste!”

He rolled his eyes at what he clearly believed was a futile promise but made no other effort to dissuade her. Easily the most compliant of her six brothers and half brothers, he rarely proved awkward. But she would have expected assent from the others, too, because as stubborn as some could be, she could be more so.

Having agreed to do as she asked, he lost little time, and now here they were with the fog growing thicker, colder, and eerier until even her own practical mind began conjuring monsters.

At last, however, the tenor call of the horn they had been waiting to hear sounded through the fog from the fortress ramparts of Claig Castle.

The oarsmen’s hands tightened on their sweeps.

“Hold water,” Ranald warned. “Sound our signal again, and listen well.”

The helmsman obeyed, blowing his two-note call.

As the sound faded eerily, Mairi heard the rhythmic splashing of oars that Ranald’s quicker ears had already discerned.

Through the fog a deep voice boomed, “Who would pass here?”

“Ranald of Isla, you villain,” Ranald bellowed back.

“Guard your steerboard oars, my lord,” the deep voice replied with an appreciative chuckle. “We’ll be upon ye straightaway.”

The dark shape of another galley’s prow loomed alongside them on the same side as the helmsman’s rudder, and as Ranald’s oarsmen on that side raised their sweeps high, she heard the other man order his to hold water. Their oars dug in instantly, bringing the approaching galley to a stop with commendable quickness.

“Welcome, my lord,” the deep voice boomed, and Mairi recognized Murdo of Knapdale, captain of Claig. “Be ye returning t’ Finlaggan, sir?”

“Aye,” Ranald said. “You did well to find us so quickly, Murdo. Would you have done so had we not sounded our horn?”

“We would,” Murdo said confidently. “I can hear fish swimming through my waters, sir. Moreover, in the unlikely event that my ears should fail, I’ve six more boats along the Sound, alert for any fool who might try t’ slip past us in this devilish fog without paying his rightful tribute.”

“Faith, sir, will each of those six stop us and demand to know our business?” Mairi demanded, fearing further delays.

“Nay, my lady,” Murdo said. “I’ll signal our code for safe passage t’ keep them at bay. Each will pass it on t’ the next, and we change our codes each night at uncertain times t’ prevent any enemy from using them to our peril. Hark now.”

He made a gesture and his helmsman sounded a series of notes from a horn pitched higher than theirs or Claig Castle’s.

A moment later, the single long note from Claig sounded again, followed almost immediately by a higher single note in the distance.

“An ye keep the high notes t’ larboard and the low ones t’ steerboard, ye’ll ha’ deep water under ye all the way, my lord,” Murdo said.

“Aye,” Ranald said, nodding to his helmsman.

Taking their beat from the helmsman, the oarsmen rowed smoothly, trusting him to steer a safe course through the Sound.

Meg peered fearfully ahead, but as near as they were now to Port Askaig, the harbor closest to Finlaggan, Mairi felt only relief. Listening as intently for the horns as they all were, no one talked, leaving her again at the mercy of her thoughts. However, now she felt more confident reaching Finlaggan in time to speak for Ian, it occurred to her that the present fog bore a similarity to the mists beclouding her future. Certainly, her progress toward it had been becalmed for some time.

Many times had her father described what that future would be and how someday, in what seemed most unlikely circumstances, she might even become Queen of Scots. But meantime she drifted with the political tide, waiting for political winds to rise and blow her in the direction his grace desired her to go. And a political tide, like any other, could turn without warning.

She had no more power to control her drifting life than to control natural or man-made tides, and in truth, she had not sought to do so. Surrounded by a loving family and esteemed for her capabilities, at times even for her opinions, she was happy enough. Unlike her younger sister Elizabeth, who flirted with every man she met, Mairi had no great longing to marry. Nor did Alasdair Stewart, the man her father had selected to be her husband, show any interest in her or in their future together. But Mairi cared even less for Alasdair, her least favorite of her royal grandfather’s multitude of sons by two wives and a long string of mistresses.

For one thing, her relationship with Alasdair lay within the second degree of consanguinity, and the Holy Kirk forbade marriage between such close kinsmen. He was four years her senior and handsome enough, she supposed, but although her father and grandfather believed the Pope would grant the necessary dispensation when the time was exactly right for requesting it, she did not want to marry her uncle.

Her half sister Marjory, on the other hand, had hardly been able to wait to marry Roderic Macleod of Lewis and Glenelg. Mairi did not envy her, though, because she now lived on the Isle of Lewis, far from Isla and Ardtornish, off the northernmost reaches of Scotland. The proud mother of three small children with a fourth on the way, Marjory would not even join them for Easter at Ardtornish.

Land loomed darkly now on both sides of the galley, and it was not long before a high-pitched horn blew the four notes that she recognized as Port Askaig’s call. Soon afterward, she heard voices and discerned the shape of her father’s wharf ahead. Men bustled about in the mist, and their helmsman shouted to make ready.

Containing her impatience only until the galley bumped against the landing and was made fast, she stood, gathering her skirts in one hand as she stepped onto a rowing bench and extended the other hand to a lad on the dock. The instant he grasped it, she stepped nimbly out onto the timber planks.

“Hold up, lass,” Ranald commanded sternly behind her. “I’ve told Ned here to run and saddle our horses, but we must wait until our baggage—”

“You may wait if it pleases you, sir,” Mairi interjected. “I’ve no time to deal with baggage if I’m to save Ian. Just saddle my horse and one for Meg as quickly as you can,” she told Ned, “for we must make haste.” Glaring at Ranald, she dared him to countermand the order.

Instead, he sighed, saying, “Saddle mine, too, Ned.” Then with a straight look at Mairi, he added, “Doubtless your lady mother is impatient to see you.”

“Aye, sir,” Mairi said. “But do send another man to help Ned, for we must not tarry. Your need for haste is not as strong as mine, so you may certainly stay to supervise the unloading if you believe it necessary. It would be good to know when his grace means to begin Ian Burk’s trial, however,” she added with a quizzical look at the lad who had helped her step onto the dock.

Frowning, he replied, “I dinna ken, my lady, though men ha’ talked o’ nowt else these past days. They did say his grace would begin when the chapel bell rings Terce, but I warrant he’ll wait till this fog lifts, or he—aye, and everyone else, too—will be gey wet afore yon trials be over.”

“But I’ve no notion what the hour is now,” Mairi said.

“You’ve time enough yet,” Ranald said.

“Unless,” the lad said, “his grace ha’ decided t’ try Ian Burk first, and indoors. If he does that, I’m thinking he’ll begin when he likes.”

“We must lose no more time then,” Mairi said with a surging horror that Ian’s fate might already be decided. “Do you come with me, Ranald, or not?”

“He’ll hold no trial within doors, Mairi. The law requires that all such gatherings be open to all. He’ll hold this trial on Council Isle as he always does.”

“He would not be so cruel as to make Ian wait,” she said fiercely. “Only look about you, Ranald. So dense a fog could last for days.”

Sighing, he told the helmsman to oversee the unloading of their baggage, holding on to Mairi’s arm as he did, as if he feared she would go without him.

“His grace should have taught you obedience,” he muttered a moment later as he hurried her along the jetty toward the steps leading up to the village. “I’m thinking he did you no service by encouraging you to speak your mind to men, but I warrant your royal husband will deal firmly with you after you are safely married.”

Grinning impudently, she said, “I am not married yet, sir, or even betrothed. Nor do I think any perhaps-someday-king Alasdair will prove a trial to me.”

Ranald chuckled. “Every one of the Steward’s sons has the Bruce’s blood in his veins, Mairi, and such men know their worth. Moreover, Alasdair is older than you, as large and strong as his father, and as likely as anyone to join his grace’s court here or at Ardtornish. We’ll see then how tolerant he is of female backchat.”

Mairi lifted her chin, determined to show no concern about Alasdair Stewart. She would deal with him later. Right now, she had a hanging to prevent.

Their horses were quickly saddled and the three miles from Askaig to Loch Finlaggan were soon behind them.

Finlaggan served as the administrative hub for the Lordship of the Isles. From the top of the rise overlooking the loch, through the still-heavy curtain of fog, the riders could barely discern the tiny village of cottages on its western shore or the sprawling, low-walled palace complex on Eilean Mòr, the larger of two islets just offshore. A stone causeway connected the islet to the village.

Council Isle, the much smaller of the two, still lay hidden in mist. Connected by a second stone causeway to Eilean Mòr at the latter’s southeastern tip, it served as a meeting place for the annual Council of the Isles, the gathering of chiefs, chieftains, lairds, and other councilors loyal to the Lord of the Isles. Only fourteen to sixteen of them served as official councilors at any time, but deliberations were open to all. No business of the Lord of the Isles was conducted in secret.

Isla’s trials, as well as appeals of decisions made elsewhere by Brehons, the hereditary judges who served throughout the Lordship, also took place on Council Isle or at Judgment Knoll, a hillside overlooking Loch Indaal on the southern end of Isla. Generally, men condemned to death in either place were hanged on the Knoll.

At the annual gathering, the councilors and his grace customarily sat around a great stone table so ancient that men said Somerled himself had held his councils there. The lad was right though, Mairi decided. If they sat around that table today, they’d be soaked through in minutes. Indeed, in so thick a fog, someone might even tumble off the causeway or stumble into the water along the shore.

From her position on the rise, she heard a rat-tat-tat of hammers that told her men had already begun their day’s work on the chapel’s new slate roof, but she could discern no activity within the complex, let alone see any on the tiny, fog-shrouded islet. Nevertheless, the sense of urgency that had driven her since learning of Ian’s trial continued to plague her. She spurred her pony forward.

No sooner had she and her companions crossed the causeway from the village to Eilean Mòr and dismounted in the grassy enclosure there than a lad of ten or eleven summers came running to help Ned with the horses.

“Has his grace already gone to Council Isle?” Mairi asked him.

“Nay, my lady, for wi’ this fog, he ha’ decided t’ hold council in the hall.”

“But can that be legal, Ranald?” she asked as Ned led the ponies away and the younger lad fell into step beside them.

“Legal enough, I warrant,” Ranald said as they passed from the grassy stable enclosure to the next one, which housed the chapel, guardhouses, and cottages. “’Tis his grace who interprets the laws, after all, and he is ever a fair man.”

“Aye, that he be,” their informer said earnestly, trotting beside Meg to keep up with them. “The laird did say the great hall will hold all who come, my lady, and he did set men like me t’ direct them there. I’m thinking his grace will begin Ian Burk’s trial first, since it be the local one, and new. That’d be within the hour.”

“I’ll just have time to change my dress then,” Mairi said, relieved that she would not have to appear before the company in her present soggy attire.

Commanding Ranald to make her excuses to her mother, and taking care to avoid anyone else who might try to delay her, she and Meg hastened across the roofed and stone-paved forecourt and up the steep stairway within the ten-foot-thick wall of the family’s private quarters, to the bedchamber she shared with her younger sister Elizabeth. There, with Meg’s help, she quickly donned an ermine-trimmed tunic and kirtle of the rich scarlet wool known as tiretain, because it had come all the way from Tyre.

Meg plaited Mairi’s glossy black hair into twin coils, pinning one over each ear, and concealed the whole beneath a delicately embroidered gold-mesh caul. Atop the caul, she set a narrow gold circlet to denote Mairi’s rank.

“Your gloves, mistress,” she said sharply when Mairi stood and turned toward the door. “And, too, you should carry a lace handkerchief.”

“Don’t be daft, Meg, I’ve tarried long enough.” But she took the gloves, knowing her mother would scold if she appeared barehanded before such a company. Then, without further comment, she hurried out and down the steep stairway, holding her long skirts away from her feet with her left hand. Her right hovered near the stone wall, but so great was her hurry that she barely touched it.

From the top of the stairs, she heard male voices below in the forecourt, but by the time she reached the doorway, silence reigned outside. Even the hammering on the chapel roof had stopped, doubtless so the workers could attend Ian’s trial.

Emerging into the empty forecourt, she bundled her skirts awkwardly over her left arm to keep them out of her way and pulled on her gloves as she hurried across the pavement and through the arched gateway into the courtyard of the vast rectangular great hall. Hurrying up the wooden steps at the hall’s southeast corner, she entered the antechamber to hear male voices again from the great hall beyond.

The door into the hall stood open to allow two tall men to pass through, one behind the other and gentlemen both if their short, brightly colored velvet cloaks and tight-fitting silk hose were any indication. As she crossed the chamber, the second man, a bit shorter and slighter than the first, reached to pull the heavy door closed behind him. The voices inside the hall were fading, telling her that her father had already mounted the dais to begin the proceedings.

“Hold there,” she commanded in a low but urgent tone as she held her skirts higher and increased her pace, fearing the man might attempt to bar the door.

It continued to close, but she caught its edge before it did.

“Wait,” she said more loudly, struggling against the strong grip that threatened to pull the door from her grasp. “I want to come in.”

The door stopped, but as she sighed her relief and moved to pass through the narrow opening, she found herself facing a broad, immobile male chest clad in sky-blue velvet, and instantly realized that she had misjudged the size of the gentleman she had thought was the smaller. The top of her head barely reached his shoulder.

At Finlaggan and elsewhere in the Isles, most men wore the skins, saffron-colored shirts, and blanketlike garments that barelegged Highlanders belted around themselves, but many of the galley-owning Islesmen, who treated the seas as their highroads, wore richer, more courtly garments that they had seen and purchased in their travels.

Thanks to her older brothers’ interest in similar garments, she recognized his short tunic as being of French design, and recalled her mother’s oft-expressed dislike of the blatant display of male backsides and sexual organs encased in thin hosiery that the fashion for such short tunics so often provided. Resisting temptation to let her gaze drift downward, she said, “Pray, sir, stand aside. Surely you know that you must leave this door open.”

“His grace, the Lord of the Isles, is about to try a man for his life, lass. Open or not, this hall is no place for a maiden today, however beautiful she may be.”

His voice was low-pitched but touched with humor.

Fighting to control her irritation, she looked up to tell the impertinent, self-appointed doorkeeper how irrelevant his opinion was to her, but she swallowed

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...