- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

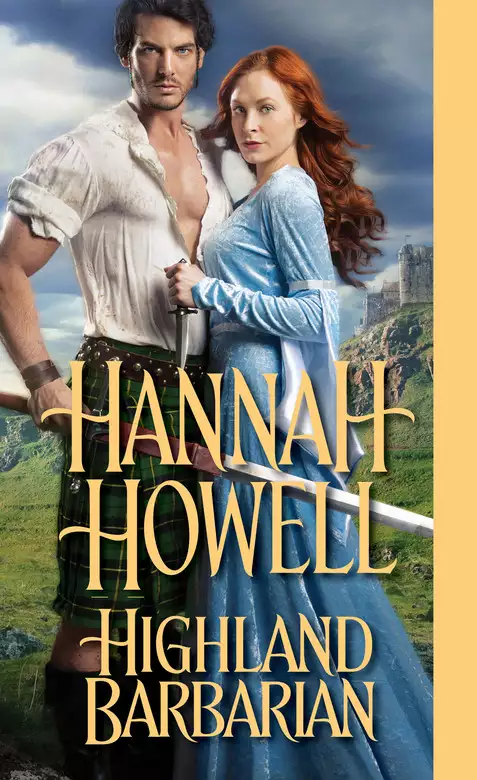

Synopsis

Sir Artan Murray was right when he decided that the dying old man who bid him collect his niece didn't know her at all. The furious woman facing him is neither "sweet" nor "biddable." She demands the brawny Highlander return her to the wedding party from which he took her. But Artan has no intention of allowing so spirited and bewitching a creature to endure a loveless marriage to a ruthless lord for her clan's sake. He aims to woo the lass and to show her that true love also yields unforgettable pleasure.

Cecily Donaldson knows a bond forged by danger and desperation cannot endure. But Artan's touch leaves her breathless, and she knows this to be her one chance to experience true passion before an arranged marriage seals her fate. Yet once begun, passion cannot be denied . . . nor can a love with the promise to change everything.

Release date: October 8, 2013

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Highland Barbarian

Hannah Howell

Summer 1480

“Ye dinnae look dead; though I think ye might be trying to smell like ye are.”

Angus MacReith scowled at the young man towering over his bed. Artan Murray was big, strongly built, and handsome. His cousin had done well, he thought. Far better than all his nearer kin who had borne no children at all or left him with ones like young Malcolm. Angus scowled even more fiercely as he thought about that man—untrustworthy, greedy, and cowardly. Artan had the blood of the MacReiths in him and it showed, just as it did in his twin, Lucas. It was only then that Angus realized Artan stood there alone.

“Where is the other one?” he asked.

“Lucas had his leg broken,” Artan replied.

“Bad?”

“Could be. I was looking for the ones who did it when ye sent word.”

“Ye dinnae ken who did it?”

“I have a good idea who did it. A verra good idea.” Artan shrugged. “I will find them.”

Angus nodded, “Aye, ye will, lad. Suspicion they will be hiding now, eh?”

“Aye, as time passes and I dinnae come to take my reckoning they will begin to feel themselves safe. ’Twill be most enjoyable to show them how mistaken they are.”

“Ye have a devious mind, Artan,” Angus said in obvious admiration.

“Thank ye.” Artan moved to lean against the bedpost at the head of the bed. “I dinnae think ye are dying, Angus.”

“I am nay weel!”

“Och, nay, ye arenae, but ye arenae dying.”

“What do ye ken about it?” grumbled Angus, pushing himself upright enough to collapse against the pillows Artan quickly set behind him.

“Dinnae ye recall that I am a Murray? I have spent near all my life surrounded by healers. Aye, ye are ailing; but I dinnae think ye will die if ye are careful. Ye dinnae have the odor of a mon with one foot in the grave. And, for all ye do stink some, ’tisnae really the smell of death.”

“Death has a smell ere it e’en takes hold of a mon’s soul?”

“Aye, I think it does. And since ye are nay dying, I will return to hunting the men who hurt Lucas.”

Angus grabbed Artan by the arm, halting the younger man as he started to move away. “Nay! I could die and ye ken it weel. I hold three score years. E’en the smallest chill could set me firm in the grave.”

That was true enough, Artan thought as he studied the man who had fostered him and Lucas for nearly ten years. Angus was still a big, strong man, but age sometimes weakened a body in ways one could not see. The fact that Angus was in bed in the middle of the day was proof enough that whatever ailed him was serious. Artan wondered if he was just refusing to accept the fact that Angus was old and would die soon.

“So, ye have brought me here to stand watch o’er your deathbed?” Artan asked, frowning, for he doubted Angus would ask such a thing of him.

“Nay, I need ye to do something for me. This ague, or whate’er it is that ails me, has made me face the hard fact that, e’en if I recover from this, I dinnae have many years left to me. ’Tis past time I start thinking on what must be done to ensure the well-being of Glascreag and the clan when I am nay longer here.”

“Then ye should be speaking with Malcolm.”

“Bah, that craven whelp is naught but a stain upon the name MacReith. Sly, whining little wretch. I wouldnae trust him to care for my dogs, let alone these lands and the people living here. He couldnae hold fast to this place for a fortnight. Nay, I willnae have him as my heir.”

“Ye dinnae have another one that I ken of.”

“Aye, I do, although I have kept it quiet. Glad of that now. My youngest sister bore a child two-and-twenty years ago. Poor Moira died a few years later bearing another child,” he murmured, the shadow of old memories briefly darkening his eyes.

“Then where is he? Why wasnae he sent here to train to be the laird? Why isnae he kicking that wee timid mousie named Malcolm out of Glascreag?”

“’Tis a lass.”

Artan opened his mouth to loudly decry naming a lass the heir to Glascreag, and then quickly shut it. He resisted the temptation to look behind him to see if his kinswomen were bearing down on him, well armed and ready to beat some sense into him. They would all be sorely aggrieved if they knew what thoughts were whirling about in his head. Words like too weak, too sentimental, too trusting, and made to have bairns not lead armies were the sort of thoughts that would have his kinswomen grinding their teeth in fury.

But Glascreag was no Donncoill, he thought. Deep in the Highlands, it was surrounded by rough lands and even rougher men. In the years he and Lucas had trained with Angus, they had fought reivers, other clans, and some who had wanted Angus’s lands. Glascreag required constant vigilance and a strong sword arm. Murray women were strong and clever, but they were healers not warriors, not deep in their hearts. Artan also considered his kinswomen unique and doubted Angus’s niece was of their ilk.

“If ye name a lass as your heir, Angus, every mon who has e’er coveted your lands will come kicking down your gates.” Artan crossed his arms over his chest and scowled at the man. “Malcolm is a spineless weasel, but a mon, more or less. Naming him your heir would at least make men pause as they girded themselves for battle. Aye, and your men would heed his orders far more quickly than they would those of a lass, and ye ken it weel.”

Angus nodded and ran one scarred hand through his black hair, which was still thick and long, but was now well threaded with white. “I ken it, but I have a plan.”

A tickle of unease passed through Artan. Angus’s plans could often mean trouble. At the very least, they meant hard work for him. The way the man’s eyes, a silvery blue like his own, were shielded by his half-lowered lids warned Artan that even Angus knew he was not going to like this particular plan.

“I want ye to go and fetch my niece for me and bring her here to Glascreag, where she belongs. I wish to see her once more before I die.” Angus sighed, slumped heavily against the pillows, and closed his eyes.

Artan grunted, making his disgust with such a pitiful play for sympathy very clear. “Then send word and have her people bring her here.”

Sitting up straight, Angus glared at him. “I did. I have been writing to the lass for years, e’en sent for her when her father and brother died ten, nay, twelve years ago. Her father’s kinsmen refused to give her into my care e’en though nary a one of them is as close in blood to her as I am.”

“Why didnae ye just go and get her? Ye are a laird. Ye could have claimed her as your legal heir and taken her. ’Tis easy to refuse letters and emissaries, but nay so easy to refuse a mon to his face. Ye could have saved yourself the misery of dealing with Malcolm.”

“I wanted the lass to want to come to Glascreag, didnae I?”

“’Tis past time ye ceased trying to coax her or her father’s kinsmen.”

“Exactly! That is why I want ye to go and fetch her here. Ach, laddie, I am sure ye can do it. Ye can charm and threaten with equal skill. Aye, and ye can do it without making them all hot for your blood. I would surely start a feud I dinnae need. Ye have a way with folk that I dinnae, that ye do.”

Artan listened to Angus’s flattery and grew even more uneasy. Angus was not only a little desperate to have his niece brought home to Glascreag, but he also knew Artan would probably refuse to do him this favor. The question was, why would Angus think Artan would refuse to go and get the woman. It could not be because it was dangerous, for the man knew well that only something foolishly suicidal would cause Artan to, perhaps, hesitate. Although his mind was quickly crowded with possibilities ranging from illegal to just plain disgusting, Artan decided he had played this game long enough.

“Shut it, Angus,” he said, standing up straighter and putting his hands on his hips. “Why havenae ye gone after the woman yourself, and why do ye think I will refuse to go?”

“Ye would refuse to help a mon on his deathbed?”

“Just spit it out, Angus, or I will leave right now and ye will ne’er ken which I might have said, aye or nay.”

“Och, ye will say nay,” Angus mumbled. “Cecily lives at Dunburn near Kirkfalls.”

“Near Kirkfalls? Kirkfalls?” Artan muttered; then he swore. “That is in the Lowlands.” Artan’s voice was soft yet sharp with loathing.

“Weel, just a few miles into the Lowlands.”

“Now I ken why ye ne’er went after the lass yourself. Ye couldnae stomach the thought of going there. Yet ye would send me into that hellhole?”

“’Tisnae as bad as all that.”

“’Tis as bad as if ye wanted me to ride to London. I willnae do it,” Artan said, and started to leave.

“I need an heir of my own blood!”

“Then ye should ne’er have let your sister marry a Lowlander. ’Tis near as bad as if ye had let her run off with a Sassanach. Best ye leave the lass where she is. She is weel ruined by now.”

“Wait! Ye havenae heard the whole of my plan!”

Artan opened the door and stared at Malcolm, who was crouched on the floor, obviously having had his large ear pressed against the door. The thin, pale young man grew even paler and stood up. He staggered back a few steps, and then bolted down the hall. Artan sighed. He did not need such a stark reminder of the pathetic choice Angus had for an heir now.

Curiosity also halted him at the door. Every instinct he had told him to keep on moving, that he would be a fool to listen to anything else Angus had to say. A voice in his head whispered that his next step could change his life forever. Artan wished that voice would tell him if that change would be for the better. Praying he was not about to make a very bad choice, he slowly turned to look at Angus, but he did not move away from the door.

Angus looked a little smug, and Artan inwardly cursed. The old man had judged his victim well. Curiosity had always been Artan’s weakness. It had caused him trouble and several injuries more times than he cared to recall. He wished Lucas were with him, for his brother was the cautious one. Then Artan quickly shook that thought aside. He was a grown man now, not a reckless child, and he had wit enough to make his own decisions with care and wisdom.

“What is the rest of your plan?” he asked Angus.

“Weel, ’tis verra simple. I need a strong mon to take my place as laird once I die or decide ’tis time I rested. Malcolm isnae it, and neither is Cecily. Howbeit, there has to be someone of MacReith blood to step into my place, the closer to me the better.”

“Aye, ’tis the way it should be.”

“So, e’en though ye have MacReith blood, ’tis but from a distant cousin. Howbeit, if ye marry Cecily—”

“Marry?!”

“Wheesht, what are ye looking so horrified about, eh? Ye arenae getting any younger, laddie. Past time ye were wed.”

“I have naught against marriage. I fully intend to choose a bride some day.”

Angus grunted. “Some day can sneak up on a body, laddie. I ken it weel. Now, cease your fretting for a moment and let me finish. If ye were to marry my niece, ye could be laird here. I would name ye my heir and nary a one of my men would protest it. E’en better, Malcolm couldnae get anyone to heed him if he cried foul. Cecily is my closest blood kin, and ye are nearly as close to me as Malcolm is. So, ye marry the lass and, one day, Glascreag is yours.”

Artan stepped back into the room and slowly closed the door. Angus was offering him something he had never thought to have—the chance to be a laird, to hold lands of his own. As the secondborn of the twins, his future had always been as Lucas’s second, or as the next in line to be the laird of Donncoill if anything happened to Lucas, something he never cared to think about. There had always been only one possibility of changing that future—marriage to a woman with lands as part of her dowry.

Which was exactly what Angus was offering him, he mused, and felt temptation tease at his mind and heart. Marry Cecily and become heir to Glascreag, a place he truly loved as much as he did his own homelands. Any man with wit enough to recall his own name would grab at this chance with both hands; yet despite the strong temptation of it all, he hesitated. Since Artan considered his wits sound and sharp, he had to wonder why.

Because he wanted a marriage like his parents had, like his grandparents had, and like so many of his clan had, he realized. He wanted a marriage of choice, of passion, of a bonding that held firm for life. When it was land, coin, or alliances that tied a couple together, the chances of such a good marriage were sadly dimmed. He had been offered the favors of too many unhappy wives to doubt that conclusion. If the thought of taking part in committing adultery did not trouble him so much, he would now be a very experienced lover, he mused and hastily shook aside a pinch of regret. He certainly did not want his wife to become one of those women, and he did not want to be one of those men who felt so little a bond with his wife that he repeatedly broke his vows; or worse, find himself trapped in a cold marriage and, bound tightly by his own beliefs, unable to find passion elsewhere.

He looked at Angus, who was waiting for an answer with an ill-concealed impatience. Although he could not agree to marry a woman he had never met, no matter how tempting her dowry, there was no harm in agreeing to consider it. He could go and get the woman and decide on marrying her once he saw her. As they traveled back to Glascreag together, he would have ample time to decide if she was a woman he could share the rest of his life with.

Then he recalled where she lived and how long she had lived there. “She is a Lowlander.”

“She is a MacReith,” Angus snapped.

Angus was looking smug again. Artan ignored it, for the man was right in thinking he might get what he wanted. In many ways, it was what Artan wanted as well. It all depended upon what this woman Cecily was like.

“Cecily,” he murmured. “Sounds like a Sassanach name.” He almost smiled when Angus glared at him, the old man’s pale cheeks now flushed with anger.

“’Tis no an English name! ’Tis the name of a martyr, ye great heathen, and weel ye ken it. My sister was a pious lass. She didnae change the child’s christening name as some folk do. Kept the saint’s name. I call the lass Sile. Use the Gaelic, ye ken.”

“Because ye think Cecily sounds English.” Artan ignored Angus’s stuttering denial. “When did ye last see this lass?”

“Her father brought her and her wee brother here just before he and the lad died.”

“How did they die?”

“Killed whilst traveling back home from visiting me. Thieves. Poor wee lass saw it all. Old Meg, her maid, got her to safety, though. Some of their escort survived, chased away the thieves, and then got Cecily, Old Meg, and the dead back to their home. The moment I heard I sent for the lass, but the cousins had already taken hold of her and wouldnae let go.”

“Was her father a mon of wealth or property?”

“Aye, he was. He had both, and the cousins now control it all. For the lass’s sake, they say. And, aye, I wonder on the killing. His kinsmen could have had a hand in it.”

“Yet they havenae rid themselves of the lass.”

“She made it home and has ne’er left there again. They also have control of all that she has since she is a woman, aye?”

“Aye, and it probably helps muzzle any suspicions about the other deaths.”

Angus nodded. “’Tis what I think. So, will ye go to Kirkfalls and fetch my niece?”

“Aye, I will fetch her, but I make no promises about marrying her.”

“Not e’en to become my heir?”

“Nay, not e’en for that, tempting as it is. I willnae tie myself to a woman for that alone. There has to be more.”

“She is a bonnie wee lass with dark red hair and big green eyes.”

That sounded promising, but Artan fixed a stern gaze upon the old man. “Ye havenae set eyes on her since she was a child, and ye dinnae ken what sort of woman she has become. A lass can be so bonnie on the outside she makes a mon’s innards clench. But then the blind lust clears away, and he finds himself with a bonnie lass who is as cold as ice, or mean of spirit, or any of a dozen things that would make living with her a pure misery. Nay, I willnae promise to wed your niece now. I will only promise to consider it. There will be time to come to know the lass as we travel here from Kirkfalls.”

“Fair enough, but ye will see. Ye will be wanting to marry her. She is a sweet, gentle, biddable lass. A true lady raised to be a mon’s comfort.”

Artan wondered just how much of that effusive praise was true, then shrugged and began to plan his journey.

“A rotting piece of refuse, a slimy, wart-infested toad, a—a—” Cecily frowned and stopped pacing her bedchamber as she tried to think of some more ways to adequately describe the man she was about to be married to, but words failed her.

“M’lady?”

Cecily looked toward where her very young maid peered nervously into the room and she tried to smile. Although Joan entered the room, she did not look very reassured, and Cecily decided her attempt to look pleasant had failed. She was not surprised. She did not feel the least bit pleasant.

“I have come to help ye dress for the start of the celebration,” Joan said as she began to collect the clothes she had obviously been told to dress Cecily in.

Sighing heavily, Cecily removed her robe and allowed the girl to help her dress for the meal in the great hall. She needed to calm herself before she faced her family, all their friends, and her newly betrothed again. Her cousins felt they were doing well by her, arranging an excellent marriage, and by most people’s reckoning, they were. Sir Fergus Ogilvey was a man of power and wealth by all accounts, was not too old, and had gained his knighthood in service to the king. She was the orphaned daughter of a scholar and a Highland woman. She was also a woman of two-and-twenty with unruly red hair, very few curves, and freckles.

She had long been a sore trial to her cousins, repaying their care with embarrassment and disobedience. It was why they were increasingly cold toward her. Cecily had tried, time and time again, to win their love and approval, but she had consistently failed. This was her last chance, and despite her distaste for the man she was soon to marry, she would stiffen her spine and accept him as her husband.

“A pustule on the arse of the devil,” she murmured.

“M’lady?” squeaked Joan.

The way Joan stared at her told Cecily that she had spoken that last unkind thought aloud and she sighed again. A part of her mind had obviously continued to think of more insults to fling at Sir Fergus Ogilvey, and her mouth had unfortunately joined in the game. The very last thing she needed was to have such remarks make their way to her cousins’ ears. She would lose all chance of gaining their affection and approval then.

“My pardon, Joan,” she said, and forced herself to look suitably contrite and just a little embarrassed. “I was practicing the saying of insults when ye entered the room and that one just suddenly occurred to me.”

“Practicing insults? Whate’er for, m’lady?”

“Why, to spit out at an enemy if one should attack. I cannae use a sword or a dagger and I am much too small to put up much of a successful fight, so I thought it might be useful to be able to flay my foe with sharp words.”

Wonderful, Cecily thought as Joan very gently urged her to sit upon a stool so that she could dress her hair, now Joan obviously thought her mistress had gone mad. Perhaps she had. It had to be some sort of lunacy to try unendingly for so many years to win the approval and affection of someone, yet she could not seem to help herself. Each failure to win the approval, the respect, and caring of her guardians seemed to just drive her to try even harder. She felt she owed them so much, yet she continuously failed in all of her attempts to repay them. This time she would not fail.

“Here now, wee Joan, I will do that.”

Cecily felt her dark mood lighten a little when Old Meg hurried into the room. Sharp of tongue though Old Meg was, Cecily had absolutely no doubt that the woman cared for her. Her cousins detested the woman and had almost completely banished her from the manor, although Cecily had never been able to find out why. To have the woman here now, at her time of need, was an unexpected blessing, and Cecily rose to hug the tall, buxom woman.

“’Tis so good to see ye, Old Meg,” Cecily said, not surprised to hear the rasp of choked-back tears in her voice.

Old Meg patted her on the back. “And where else should I be when my wee Cecily is soon to be wed, eh?” She urged Cecily back down onto the stool and smiled at Joan. “Go on, lassie. I will do this. I suspicion ye have a lot of other things ye must see to.”

“I hope ye havenae hurt her feelings,” Cecily murmured as soon as Joan was gone and Old Meg shut the door.

“Nay, poor lass is being worked to the bone, she is, and is glad to be relieved of at least one chore. Your cousins are twisting themselves into knots trying to impress Ogilvey and his kin. They dinnae seem to ken that he is naught but a grasper who thinks himself so high and mighty he wouldst probably look down his long nose at one of God’s angels.”

Cecily laughed briefly, but then frowned. “He does seem to be verra fond of himself.”

Old Meg harrumphed as she began to vigorously brush Cecily’s hair. “He is so full of himself he ought to be gagging. The mon is acting as if he does ye some grand favor by agreeing to wed with ye. Ye come from far better stock than that prancing mongrel.”

“He was knighted in the service of the king,” Cecily felt moved to say even though she felt no real compulsion to defend the man.

“The fool stumbled into the way of a sword that would have struck our king, nay more than that. It wasnae until Ogilvey paused a wee moment in cursing and whining—after he had recovered from his swoon, mind ye—that he realized everyone thought he had done it apurpose. The sly cur did have the wit to play the humble savior of our sire, I will give ye that, although he did a right poor job of it.”

“How do ye ken so much about it?”

“I was there, wasnae I? I was visiting my sister. We were watching all the lairds and the king. Some foolish argument began between a few of the lairds, swords were drawn, and the king nearly walked into one save that Ogilvey was so busy brushing a wee speck of dirt off his cloak he wasnae watching where he was going. Tripped o’er his own feet and stumbled into glory, aye.”

Cecily frowned. “He has only e’er said that he did our king a great service. Verra humble about it all he is.”

“Weel, he cannae tell the truth about it, can he? Nay when he let the mistake stand and got himself knighted and all.”

So she was soon to marry a liar, Cecily thought, and inwardly sighed. That might be an unfair judgment. It could well have been impossible for Sir Fergus to untangle himself from the misconception. After all, who would dare argue with a king? And why was she wearying her mind making excuses for the man, she asked herself.

Because she had to was the answer. This was her last chance to become a part of this family, to be more than a burden and an object of charity. Although she would have to leave to abide in her husband’s home, at least she could leave her cousins thinking well of her and ready to finally consider her a true and helpful part of their family. She would be welcome in their hearts and their home at last. Sir Fergus was not a man she would have chosen for the father of her children, but few women got to choose their husbands. Poor though she felt the choice was, however, she could take comfort in the fact that she had finally done something to please her kinsmen.

“Ye dinnae look to be too happy about this, lass,” said Old Meg as she decorated Cecily’s thick hair with blue ribbons to match her gown.

“I will be,” Cecily murmured.

“And just what does that mean, eh? I will be.”

“It means I will be content in my marriage. And, aye, I shall have to work to be so, but it will suffice. I am nearly two-and-twenty. ’Tis past time I was married and bred a few bairns. I but pray they dinnae get his chin,” she muttered, then grimaced when Old Meg laughed. “That was unkind of me.”

“Mayhap, but ’twas the hard, cold truth. The mon has no chin at all, does he.”

“Nay, I fear not. I have ne’er seen such a weak one. ’Tis as if his neck starts at his mouth.” Cecily shook her head, earning a sharp reprimand from Old Meg.

“If ye dinnae wish to be wed to the fool, why have ye agreed to this?”

“Because Anabel and Edmund want this.”

When Old Meg stepped back to put her hands on her ample hips and scowl at her, Cecily stood up and moved to the looking glass to see if she was presentable. The looking glass was one of the few richer items in her small bedchamber, and if Cecily stood a little to the side, she could see herself quite well despite the large crack in it. She felt that small worm of resentment in her heart twitch over being given only the things Anabel or her daughters no longer wanted or that were marred in some way, but she smothered it. Anabel could have just thrown the cracked looking glass away as she had so much else that had belonged to Cecily’s mother.

Cecily frowned as she realized she would have to plot some way to slyly retrieve a few things from hiding. She glanced toward a still scowling Old Meg. One of the woman’s most often voiced complaints was about how Anabel had tossed away so many of Moira Donaldson’s belongings. It was, perhaps, time to let the woman know that not everything was lost. At first, it had just been a child’s grief that had caused Cecily to retrieve her mother’s things and hide them away. Over the years, it had slowly become a ritual and, she ruefully admitted to herself, a form of rebellion.

The same could be said for her other great secret, she mused, glancing toward the small ornately carved chest holding her ribbons and the meager collection of jewelry al. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...