THE HUSBAND STITCH

(If you read this story out loud, please use the following voices:

ME: as a child, high-pitched, forgettable; as a woman, the same.

THE BOY WHO WILL GROW INTO A MAN, AND BE MY SPOUSE: robust with serendipity.

MY FATHER: kind, booming; like your father, or the man you wish was your father.

MY SON: as a small child, gentle, sounding with the faintest of lisps; as a man, like my husband.

ALL OTHER WOMEN: interchangeable with my own.)

In the beginning, I know I want him before he does. This isn’t how things are done, but this is how I am going to do them. I am at a neighbor’s party with my parents, and I am seventeen. I drink half a glass of white wine in the kitchen with the neighbor’s teenage daughter. My father doesn’t notice. Everything is soft, like a fresh oil painting.

The boy is not facing me. I see the muscles of his neck and upper back, how he fairly strains out of his button-down shirts, like a day laborer dressed up for a dance, and I run slick. And it isn’t that I don’t have choices. I am beautiful. I have a pretty mouth. I have breasts that heave out of my dresses in a way that seems innocent and perverse at the same time. I am a good girl, from a good family. But he is a little craggy, in that way men sometimes are, and I want. He seems like he could want the same thing.

I once heard a story about a girl who requested something so vile from her paramour that he told her family and they had her hauled her off to a sanatorium. I don’t know what deviant pleasure she asked for, though I desperately wish I did. What magical thing could you want so badly they take you away from the known world for wanting it?

The boy notices me. He seems sweet, flustered. He says hello. He asks my name.

I have always wanted to choose my moment, and this is the moment I choose.

On the deck, I kiss him. He kisses me back, gently at first, but then harder, and even pushes open my mouth a little with his tongue, which surprises me and, I think, perhaps him as well. I have imagined a lot of things in the dark, in my bed, beneath the weight of that old quilt, but never this, and I moan. When he pulls away, he seems startled. His eyes dart around for a moment before settling on my throat.

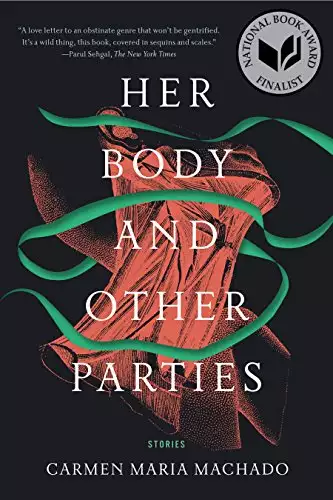

“What’s that?” he asks.

“Oh, this?” I touch the ribbon at the back of my neck. “It’s just my ribbon.” I run my fingers halfway around its green and glossy length, and bring them to rest on the tight bow that sits in the front. He reaches out his hand, and I seize it and press it away.

“You shouldn’t touch it,” I say. “You can’t touch it.”

Before we go inside, he asks if he can see me again. I tell him that I would like that. That night, before I sleep, I imagine him again, his tongue pushing open my mouth, and my fingers slide over myself and I imagine him there, all muscle and desire to please, and I know that we are going to marry.

…

We do. I mean, we will. But first, he takes me in his car, in the dark, to a lake with a marshy edge that is hard to get close to. He kisses me and clasps his hand around my breast, my nipple knotting beneath his fingers.

I am not truly sure what he is going to do before he does it. He is hard and hot and dry and smells like bread, and when he breaks me I scream and cling to him like I am lost at sea. His body locks onto mine and he is pushing, pushing, and before the end he pulls himself out and finishes with my blood slicking him down. I am fascinated and aroused by the rhythm, the concrete sense of his need, the clarity of his release. Afterward, he slumps in the seat, and I can hear the sounds of the pond: loons and crickets, and something that sounds like a banjo being plucked. The wind picks up off the water and cools my body down.

I don’t know what to do now. I can feel my heart beating between my legs. It hurts, but I imagine it could feel good. I run my hand over myself and feel strains of pleasure from somewhere far off. His breathing becomes quieter and I realize that he is watching me. My skin is glowing beneath the moonlight coming through the window. When I see him looking, I know I can seize that pleasure like my fingertips tickling the very end of a balloon’s string that has almost drifted out of reach. I pull and moan and ride out the crest of sensation slowly and evenly, biting my tongue all the while.

“I need more,” he says, but he does not rise to do anything. He looks out the window, and so do I. Anything could move out there in the darkness, I think. A hook-handed man. A ghostly hitchhiker forever repeating the same journey. An old woman summoned from the repose of her mirror by the chants of children. Everyone knows these stories—that is, everyone tells them, even if they don’t know them—but no one ever believes them.

His eyes drift over the water and then return to me.

“Tell me about your ribbon,” he says.

“There’s nothing to tell. It’s my ribbon.”

“May I touch it?”

“No.”

“I want to touch it,” he says. His fingers twitch a little, and I close my legs and sit up straighter.

“No.”

Something in the lake muscles and writhes out of the water, and then lands with a splash. He turns at the sound.

“A fish,” he says.

“Sometime,” I tell him, “I will tell you the stories about this lake and her creatures.”

He smiles at me, and rubs his jaw. A little of my blood smears across his skin, but he doesn’t notice, and I don’t say anything.

“I would like that very much,” he says.

“Take me home,” I tell him. And like a gentleman, he does.

That night, I wash myself. The silky suds between my legs are the color and scent of rust, but I am newer than I have ever been.

My parents are very fond of him. He is a nice boy, they say. He will be a good man. They ask him about his occupation, his hobbies, his family. He shakes my father’s hand firmly, and tells my mother flatteries that make her squeal and blush like a girl. He comes around twice a week, sometimes thrice. My mother invites him in for supper, and while we eat I dig my nails into the meat of his leg. After the ice cream puddles in the bowl, I tell my parents that I am going to walk with him down the lane. We strike off through the night, holding hands sweetly until we are out of sight of the house. I pull him through the trees, and when we find a patch of clear ground I shimmy off my pantyhose, and on my hands and knees offer myself up to him.

I have heard all of the stories about girls like me, and I am unafraid to make more of them. I hear the metallic buckle of his pants and the shush as they fall to the ground, and I feel his half hardness against me. I beg him—“No teasing”—and he obliges. I moan and push back, and we rut in that clearing, groans of my pleasure and groans of his good fortune mingling and dissipating into the night. We are learning, he and I.

There are two rules: he cannot finish inside of me, and he cannot touch my green ribbon. He spends into the dirt, pat-pat-patting like the beginning of rain. I go to touch myself, but my fingers, which had been curling in the dirt beneath me, are filthy. I pull up my underwear and stockings. He makes a sound and points, and I realize that beneath the nylon, my knees are also caked in dirt. I pull my stockings down and brush, and then up again. I smooth my skirt and repin my hair. A single lock has escaped his slicked-back curls in his exertion, and I tuck it up with the others. We walk down to the stream and I run my hands in the current until they are clean again.

We stroll back to the house, arms linked chastely. Inside, my mother has made coffee, and we all sit around while my father asks him about business.

(If you read this story out loud, the sounds of the clearing can be best reproduced by taking a deep breath and holding it for a long moment. Then release the air all at once, permitting your chest to collapse like a block tower knocked to the ground. Do this again, and again, shortening the time between the held breath and the release.)

…

I have always been a teller of stories. When I was a young girl, my mother carried me out of a grocery store as I screamed about toes in the produce aisle. Concerned women turned and watched as I kicked the air and pounded my mother’s slender back.

“Potatoes!” she corrected when we got back to the house. “Not toes!” She told me to sit in my chair—a child-sized thing, built for me—until my father returned. But no, I had seen the toes, pale and bloody stumps, mixed in among those russet tubers. One of them, the one that I had poked with the tip of my index finger, was cold as ice, and yielded beneath my touch the way a blister did. When I repeated this detail to my mother, something behind the liquid of her eyes shifted quick as a startled cat.

“You stay right there,” she said.

My father returned from work that evening, and listened to my story, each detail.

“You’ve met Mr. Barns, have you not?” he asked me, referring to the elderly man who ran this particular market.

I had met him once, and I said so. He had hair white as a sky before snow, and a wife who drew the signs for the store windows.

“Why would Mr. Barns sell toes?” my father asked. “Where would he get them?”

Being young, and having no understanding of graveyards or mortuaries, I could not answer.

“And even if he got them somewhere,” my father continued, “what would he have to gain by selling them amongst the potatoes?”

They had been there. I had seen them with my own eyes. But beneath the sunbeam of my father’s logic, I felt my doubt unfurl.

“Most importantly,” my father said, arriving triumphantly at his final piece of evidence, “why did no one notice the toes except for you?”

As a grown woman, I would have said to my father that there are true things in this world observed only by a single set of eyes. As a girl, I consented to his account of the story, and laughed when he scooped me from the chair to kiss me and send me on my way.

It is not normal that a girl teaches her boy, but I am only showing him what I want, what plays on the insides of my eyelids as I fall asleep. He comes to know the flicker of my expression as a desire passes through me, and I hold nothing back from him. When he tells me that he wants my mouth, the length of my throat, I teach myself not to gag and take all of him into me, moaning around the saltiness. When he asks me my worst secret, I tell him about the teacher who hid me in the closet until the others were gone and made me hold him there, and how afterward I went home and scrubbed my hands with a steel wool pad until they bled, even though the memory strikes such a chord of anger and shame that after I share this I have nightmares for a month. And when he asks me to marry him, days shy of my eighteenth birthday, I say yes, yes, please, and then on that park bench I sit on his lap and fan my skirt around us so that a passerby would not realize what was happening beneath it.

“I feel like I know so many parts of you,” he says to me, knuckle-deep and trying not to pant. “And now, I will know all of them.”

There is a story they tell, about a girl dared by her peers to venture to a local graveyard after dark. This was her folly: when they told her that standing on someone’s grave at night would cause the inhabitant to reach up and pull her under, she scoffed. Scoffing is the first mistake a woman can make.

“Life is too short to be afraid of nothing,” she said, “and I will show you.”

Pride is the second mistake.

She could do it, she insisted, because no such fate would befall her. So they gave her a knife to stick into the frosty earth, as a way of proving her presence and her theory.

She went to that graveyard. Some storytellers say that she picked the grave at random. I believe she selected a very old one, her choice tinged by self-doubt and the latent belief that if she were wrong, the intact muscle and flesh of a newly dead corpse would be more dangerous than one centuries gone.

She knelt on the grave and plunged the blade deep. As she stood to run—for there was no one to see her fear—she found she couldn’t escape. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved