- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

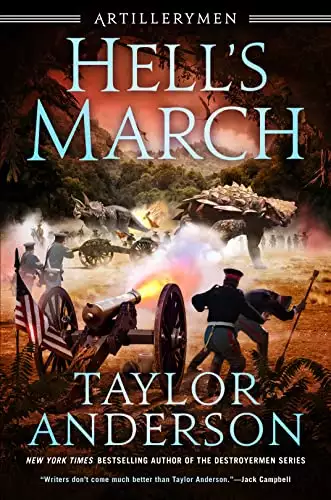

Major Lewis Cayce will need to use every weapon in his arsenal to keep his stranded men alive on a deadly alternate Earth in this gripping new adventure set in the world of the New York Times bestselling Destroyermen series.

It is 1847, and almost a full year after being shipwrecked on another, far stranger and more dangerous Earth on their way to fight Santa Anna in the Mexican-American War, Lewis Cayce and his small group of artillerymen, infantrymen, and dragoons have made friends in the Yucatán, helped build an army, and repulsed the first efforts of the blood-drenched Holy Dominion to wipe their new friends out.

As an even more radical cult of Blood Priests arises and begins to pursue its own path to power, the Dominion can’t let its defeat stand. It must crush the heretics and expel them from the land it has claimed.

Fortunately, Lewis Cayce is a professional. He understands defense can only result in a stalemate at best, and a stalemate with the more populous Dominion will only lead to defeat in the end. The lucky few will be enslaved. The rest will be sacrificed in the most horrific way imaginable. The only hope his new allies have is to win—and to do that, his little army must attack the most powerful and diabolical enemy on the planet in its own territory. Achieving victory will take all Lewis’s imagination, the courage and trust of his soldiers—and all the round shot and canister his tiny band of artillerymen can slam out.

Release date: September 27, 2022

Publisher: Ace

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hell's March

Taylor Anderson

CHAPTER 1

NOVEMBER 1847

1ST DIVISION / NAUTLA / YUCATÁN PENINSULA

The sun stood bright and hot over the “ruined” city of Nautla on the west coast of the Yucatán, which was being hacked back out of the dense surrounding forest even while other labor was under way to reclaim it. Like the larger, even more ancient Campeche to the south, it boasted finely fitted stone walls around impressive dwellings and other structures, as well as the seemingly ubiquitous central stepped pyramid that appeared to grace every city of any size in the region. Unlike distant Campeche, however, Nautla’s condition wasn’t a result of centuries of neglect. Right on the edge of the Contested Lands, or “La Tierra de Sangre,” largely controlled by Holcano Indians and furry-feathery, extremely ferocious, “Grik-like” beings (these struck most as a terrifying cross between vultures and alligators with their upright physiques, raptor claws, and toothy jaws), Nautla had received too much attention over the last several decades. First conquered by Holcanos about fifty years earlier, it became almost a traditional battlefield for Holcanos and Ocelomeh Jaguar Warriors to trade back and forth. The Ocelomeh were never as numerous and used imaginative tactics, especially after the arrival of Har-Kaaska and his Mi-Anakka (vaguely catlike folk from an unnamed land shipwrecked there twenty years before). They finally made a serious attempt to permanently liberate the city a decade ago, but never induced enough people to return and make it prosper. They gave up. It had “belonged” to the Holcanos ever since, though its only real inhabitants were bands of wild “garaaches,” essentially young feral Grik that hadn’t joined a tribe. They were a menace to everyone, even their own species, and Grik and Holcanos both hunted and ate them.

Despite years of fighting in and around Nautla, the combatants hadn’t possessed the means to seriously damage its durable structures, and it remained largely intact. Troops under the command of the Blood Cardinal Don Frutos of the “Holy Dominion”—a power based on a warped mix of centuries-old Spanish Catholic Christianity and Mayan-Aztecan blood ritual, dominating most of what should’ve been Mexico and Central America and bent on conquest and subjugation—had briefly bombarded it when they passed through. They’d only been exercising their gun’s crews in preparation for knocking down the walls of the independent northern coastal city of Uxmal when they got there, so the damage hadn’t been severe.

But Don Frutos had been stopped short of his objective at the “Battle of the Washboard” by a small army led by Major Lewis Cayce, composed of recognizably Christian natives of the Yucatán and their pagan Ocelomeh protectors and trained by American castaways from “another” earth who’d been bound for a different Vera Cruz to join Winfield Scott’s campaign against the president of Mexico. And just like this different earth, the geography of war had changed very little. The ultimate enemy (besides the land itself and wildly ferocious predators) styled himself “His Supreme Holiness, Messiah of Mexico, and by the Grace of God, Emperor of the World,” and ironically ruled from the same . . . but different . . . Valley of Mexico. Major Cayce’s roughly seven hundred American survivors were no longer engaged in a political war, however—a spat between neighboring countries over past grievances and territory. They’d joined in a war of survival against an existential threat and had a cause they could all believe in: build a strong Union of threatened city-states, oppose the Dominion—and hopefully survive. The odds were very long indeed. Major Cayce followed his victory over the “Doms” by marching his still largely American Detached Expeditionary Force and the 1st Uxmal and 1st Ocelomeh Regiments down to fortify Nautla into an impassable strongpoint astride the Camino Militar. So far, the most difficult tasks had been rooting out garaaches, repairing the walls and backing them with earth to better resist Dom artillery, and cleaning out years of accumulated filth to make the place tolerably sanitary. The first priority in this respect had been to fill in the hopelessly fouled freshwater wells and dig new ones. Nautla was “alive” again in a sense, but as a formidable fort, not a city. It was in this light Lewis Cayce surveyed it now, standing on the south wall with a collection of his officers and some luminaries from Uxmal; friends, he hoped and believed.

“This isn’t exactly what I meant when I urged you to take the war to the Doms,” said Alcaldesa Sira Periz in a dissatisfied tone. Tiny, dark, and beautiful, she’d become the ruler of Uxmal when her husband was killed in a treacherous parley before the Battle of the Washboard began. Her suite of advisors included a shrewd, also beautiful Englishwoman named Samantha Wilde and the oddly inseparable Reverend Samuel Harkin—a tall, bearded, overweight Presbyterian—and Father Orno—a short, slight, Uxmalo priest from a vaguely Jesuit tradition. They’d been brought down by the wiry, craggy-faced Captain Eric Holland in HMS Tiger, an elderly, lightly armed, retired British man-o’-war that had been carrying European passengers like Samantha away from the “old” Vera Cruz after General Scott’s invasion there. She’d only incidentally been close to the American Mary Riggs, Xenophon, and Commissary, and the sailing steamer Isidra(taking troops to join General Scott’s campaign) when they were all so . . . bizarrely and cataclysmically swept to this world by an appalling—some said “supernatural”—storm. Mary Riggs and Xenophon actually “fell” to earth miles inland, and Commissarycrashed down on the beach. All were hopelessly wrecked with great loss of life except Isidra, now in the hands of the Doms, and Tiger, which they’d repaired and put to use. Old and decrepit on the world she came from, Tiger was the fastest, most capable ship the Allied cities had at their disposal. Sadly, most of her passengers had been carried away to “safety” by Isidra and had likely been gruesomely sacrificed to the bloodthirsty underworld God of the Doms. At best, they still lived in slavery.

Sira Periz was dwarfed by most around her, standing near one of the new embrasures for cannon captured at the Washboard like a bronze-skinned pixie in a dark green dress covered by gold scale armor. As was customary for widows still in mourning, her long, jet-black hair hung loose around her shoulders. Uxmalo women accepting suitors gathered their hair behind their heads (to best display their pretty faces, believed most of the young American soldiers). Sira looked particularly small beside the tall, broad-shouldered Lewis Cayce. Instead of his usual dark blue shell jacket that all mounted forces now wore (distinguished only by red artillery trim in his case), he’d donned his fine, single-breasted frock coat and crimson sash under a white saber belt for the alcaldesa’s visit. Otherwise, he still wore the standard wheel hat and sky-blue trousers used by all the branches, but his trousers were tucked into knee-high boots, carefully blacked and polished by his scrawny, villainous-looking orderly, Corporal Willis, of the 1st Artillery. Lewis had apparently even allowed the man to closely trim his hair and thick brown beard. He was adamant that all the people in “his” army, Americans or not, maintain the highest degree of uniformity and hygiene—particularly under their strange circumstances—and demanded all the Allied cities provide proper uniforms for their people. Not only did he believe that men who looked like soldiers tended to act like them, he wanted all his troops, no matter where they were from or which regimental flags they flew (locals who hadn’t joined “American” units fought under their city-state flags), to look and feel like one combined army, united by a common cause.

“I believe what the alcaldesa means,” rumbled Reverend Harkin in his deep pulpit voice, “is that she hoped you might be able to do more than just come down and retake Nautla—and stop.”

Lewis smiled. “I know. But that’s already more than the enemy would’ve expected. Even their General Agon, a cut above the rest, I believe, probably thought we’d lick our wounds at Uxmal and wait for them to come at us again. He can’t have any idea that King Har-Kaaska and Second Division have already driven down to relieve Itzincab in the east, and are pushing his Holcano allies back toward Puebla Arboras.” Puebla Arboras had been the southernmost “Allied” city, but its alcalde, Don Discipo, had given it over to the enemy. “Agon will see this as an aggressive step,” Lewis continued, “but still essentially defensive. More than he expected, like I said, and therefore as much as he’ll think we’re capable of. It’ll focus his attention.”

Another tall man, Captain Giles Anson, formerly of the Texas Mounted Rifles (or Rangers), chuckled lightly. He was lankier than Lewis, with a graying beard, and wore the plain blue jacket of a Ranger. Instead of a saber belt, he was burdened by a pair of huge Walker Colts in holsters on a waistbelt, suspended by braces, and a pair of smaller Paterson Colts in holsters attached to them high on his chest, almost under his arms. “You know how our Lewis is,” he reminded with a combination of irony and fondness. The two men had known each other but hadn’t been friends before they wound up here. Now they were. “Always focusin’ the enemy on one thing . . .”

“While he does another!” burst out Varaa-Choon, clapping her hands. Varaa was a Mi-Anakka, one of only six known on this continent and the first the Americans ever met. Wearing silver scale armor over a reddish leather tunic covering dark tan fur—and with a long, fluffy tail that often seemed to have a mind of its own—she was also most emphatically not human. She claimed to be forty, but there was no white fur around her nose and mouth, only lighter and darker highlights around impossibly large blue eyes the color of the afternoon sky. She and her then more numerous companions were shipwrecked here twenty years before and taken for minions of a feline deity the Ocelomeh worshipped in their distant past. (This was particularly strange since, though Mi-Anakka did bear a certain resemblance to cats, as far as anyone knew, there were no Jaguars on this world.)

Their leader, now King Har-Kaaska, gradually corrected his follower’s beliefs, but Mi-Anakka remained in positions of leadership among the Jaguar Warriors, more effectively guiding them in their apparently self-appointed, mutually beneficial role as protectors to the more peaceful and civilized peoples of the Yucatán. Varaa Choon was Har-Kaaska’s female “Warmaster” and liaison to the Allied Army in the west. Devoted to her king and his interests, not to mention the Ocelomeh in the army, she’d also become a close friend to the Americans and was a trusted advisor and battlefield commander in her own right. Friend or not, there was only one subject she would never speak on, out of concern the Doms might eventually learn it too: where her people came from.

“Like last time,” agreed Lieutenant Leonor Anson in a husky voice. The Ranger’s daughter was almost as tall as him, having effectively passed as a young man in her father’s Ranger company. Everyone knew she was a woman now, considered very pretty when she gave a rare smile instead of just boyishly handsome, and she no longer stuffed the shoulder-length black hair of her Mexican mother up in her hat. Nor did she tie it in back in the local style for a variety of reasons. She’d been . . . abused by straggling Mexican soldiers during the war for Texas’s independence a decade before, and the “girl” she’d been was virtually extinguished, her mother and brothers killed. Her father had been with Houston’s army, and she was all he had left. He couldn’t leave her behind again, so she grew up fighting Comanches and Mexican border incursions like a wildcat at his side. All that resulted in a somewhat . . . limited social development and an implacable hatred of Mexicans only now beginning to fade as she slowly befriended the young (newly promoted) Capitan Ramon Lara, also standing by. Lara was an agreeable young man, brave, resourceful, and funny, all of which earned Leonor’s respect. He’d been in charge of a scouting force of Mexican soldiers onshore that was also . . . brought . . . wherever they were, by the same freak occurrence that dumped the Americans here. He now led the 1st Yucatán Lancers under Captain Anson’s overall command, as were all the Rangers and dragoons.

Leonor still dressed and acted like a man in the field, even though she’d been taken under the wing of Samantha Wilde and her French friend, Angelique Mercure. Both ladies were abandoned by Isidra on the beach with Commissary’s survivors. Fortunate for them, as it turned out. But under their influence, Leonor had taken a few tentative steps toward becoming a “lady,” when she deemed it appropriate. Still a fighter, however, she’d earned the men’s respect as such with her own pair of Paterson Colts, often leading scouts. Otherwise, she stayed busy at her self-appointed task as aide and protector for her father—and now Lewis Cayce, whom she had secret, complicated feelings for.

Lewis smiled and nodded at her. “Like last time,” he agreed. “The smaller force, and I expect we’ll almost always be, must do the unexpected.”

“I hope Tiger’ll have a bigger part in whatever you cook up this time,” Captain Holland groused.

Lewis grinned at the old sailor, now in uniform as well, but still wearing his gray hair long and unbound. He looked eighty, but couldn’t be. Even if he was only sixty, he was as strong and fit as a man half that age. He’d been master of the privately owned transport Mary Riggs, but spent time in the navy and knew how to fight a ship. Once referencing going through the grinder with Porter at Valparaiso back in 1814, he wasn’t fond of the British and passionately hated carronades. He’d gone out to Tiger, lying helpless and dismasted at anchor offshore, and taken charge of her demoralized skeleton crew. Her owner and master had left with her passengers in Isidra to “get help.” From what they’d learned of those people’s fate, Holland figured Tiger’s skipper was the only one who deserved it. The ship was unquestionably “his” now, manned by the surviving sailors of all the wrecks and some Uxmalo fishermen.

“Stop complaining,” Samantha Wilde told Holland, rolling her eyes and briskly waving her little folding fan. Like Sira Periz, she was dressed in green, a classy but sensible day dress complementing the curly blonde hair escaping from the wide-brimmed, low-crowned straw hat on her head. Like them all, she was perspiring, and the fan was useless against the heat, but it served as a—probably unconscious—manifestation of her moods. Impatience, in this instance. “You’ve had considerable excitement of late!” she exclaimed.

Tiger had all her heavier, lower-tier guns removed when she was sold out of service—she was sixty years old and couldn’t bear their weight anymore—but her twenty upper-deck 12pdrs and ten 6pdrs had been more than a match for several Dom transports and now two armed enemy galleons snooping around the mouth of Uxmal Bay. There’d been no survivors from either one since Dom naval officers had been early converts to the even more radical “Blood Priests” who were gaining power in the Dominions and apparently had the same “victory or death” mindset as their upper-class hidalgo lancers. In the first instance, they’d murdered their surviving crew and then themselves after their ship was hopelessly bilged on coral heads inside the bay itself. In the second, after being disabled, they burnt the ship with everyone aboard. The horrifically voracious predators in the sea on this world quickly devoured those who jumped in the water.

The same wasn’t true for the transports Tiger caught, loaded with supplies for Don Frutos’s army. Their officers had been taken, too afraid to kill themselves, but then even more fearful of talking—at first. The fate of their souls was a factor, but they were more concerned what would happen to them if they were “rescued.” Their crews were another matter. Nearly all were slaves, terrified and expecting to be murdered, eaten—who knew what—by demon and heretic captors. They were so pathetically grateful when treated well, Holland thought he could use them when their shock wore off. Granted, they’d been enslaved in conquered territories and were deemed “heretics” themselves, but Varaa said slaves often acted as rabid as Blood Priests to “prove” they’d converted. Lewis considered. Either way, it’s the first indication the perverted “True Faith” of the Holy Dominion isn’t all-pervasive, even where it’s been long-established.

“I did, a little,” Holland agreed, “an’ the prize money for the cargoes was appreciated by the lads.”

Sira Periz waved that away. “A small payment to your crew was cheaper than producing the goods and ships.”

“I’m most thankful for the part of the cargo coming to us,” asserted Captain Elijah Hudgens, commanding C Battery. His accent left no doubt that, like Tiger, he was born in Britain. Lewis suspected nearly half his six hundred or so surviving Americans had been immigrants to the United States—before they came here. So many factions, so many rivalries! But maybe that’s for the best. All those factions from that world and this have fused into a surprisingly cohesive “us” against the “them” of the Doms. He shook his head and looked back at Hudgens, who was also responsible for emplacing ten of the twenty field guns they’d captured at the Battle of the Washboard.

“All that gunpowder and copper roundshot for these ugly buggers,” Hudgens continued, gesturing at the nearest weapon. “The powder’s not as good as the ‘powder monks’ are making at Uxmal now, but it’ll do. And we needed more roundshot than we captured with the guns. It’s all the wrong bloody size!” He elaborated, waving at the closest cannon again. The tube was bronze and reasonably well-made, but American guns (and the British ones on Tiger) were bored for six- and twelve-pound shot, a little more than 3.5 and 4.5 inches in diameter, respectively. Dom field guns were 8pdrs and required a ball just under four inches in diameter. A whole different size they’d have to make. The captured cargo gave them more time to do so. The “ugly” part Hudgens objected to most was the bright yellow–painted, split-trail, solid-wheel carriage. It was ridiculously heavy, bulky, and entirely unsuited to rapid movement around the battlefield. “Proper” carriages were under construction back in Uxmal and elsewhere for the captured cannon, even the giant siege guns they’d taken, but emplaced in the walls of Nautla, these didn’t need them yet.

Looking back at Holland, Lewis asked, “There were charts in the transports you took?”

“Aye.” Holland grinned. “Crude, ugly sketches showin’ little more than the Caribbean, an’ all lookin’ like somethin’ Magellan or Cabrillo would’a scribbled.”

“I don’t know who they are,” Varaa said, “but remember, the shorelines on this world are not the same as yours. The charts may be quite accurate.”

Holland frowned. “Don’t see how. It gets really strange down past the Mosquito Kingdom . . . area. . . .” He shrugged. The Mosquito Kingdom didn’t exist here, of course.

Lewis wasn’t interested in south at the moment. “What about Vera Cruz?”

Holland dipped his head and sobered. “I was hopin’ you’d ask about that. When the merchant officers we caught started talkin’, they confirmed Isidra’s there. Maybe some o’ her people.” He scratched his bristly chin. “No idea if she’s fit for sea or her engineerin’ plant’s in one piece—regular folks don’t ask questions like that—but the stack’s been down, then back up, an’ there’s been a lot o’ comin’ an’ goin’ aboard, aside from general repairs.” He frowned. “Hafta assume they’ve drawn plans o’ ever’thin’ in her by now.”

Varaa frowned and blinked rapidly, tail swishing behind her. Lewis knew she and King Har-Kaaska were concerned the Doms would develop steam-powered ships and eventually threaten their homeland. Wherever that was. Lewis didn’t like it either, but without information, there’d been nothing they could do. Now . . . ?

“On the bright side . . . maybe,” Holland continued, “they’ve replaced her masts an’ crossed her yards. No sails hoisted last time our fellas saw, but they’ve had time to sew a suit an’ get it up by now. Prob’ly won’t risk actually operatin’ her without backup. We might still cut her out before they do. Deprive ’em of experience if not a design.” He paused. “Wouldn’t want to try it if she can’t make sail, mind. We’d never tow her clear. There’s usually two or three warships like we already handled in Vera Cruz. Wouldn’t concern me if we could maneuver,” he said disdainfully, “but luggin’ Isidra, they’d pick us apart. Them an’ the shore batteries.”

“Shore batteries?” Lewis asked.

“Aye. Big devils. 36pdrs like those siege guns you captured. Confirmed that by talkin’ to the transport crews, though they don’t hardly know how to tell us what we want to know, if you get my meanin’. Most’a the poor devils ain’t allowed ashore an’ some can hardly speak. More like dogs than men. Prob’ly been cooped up on ships since they was nippers, just doin’ what they’re told. Ask ’em about shoals an’ some might know. Ask about shore batteries an’ they know they’re there, just nothin’ about ’em. Hafta get the officers to draw things up better if they can.” He chuckled. “It finally dawned on ’em their best chance o’ livin’ is if they don’t get rescued, so one, at least, is bein’ more cooperative.” He paused and rubbed his stubble again. “I did get that the Doms don’t have many warships in the Atlantic. Seems they’re more worried about the Pacific.” He glanced at Varaa. “Them ‘New Britain Isles Imperials,’ er whatever they are.”

No one knew much about the “Empire of the New Britain Isles” except its people were—apparently—British, or descendants of British sailors who’d come to this world just like them at some point and were based out in the Pacific. Other than that, it was believed they were enemies of the Doms, but also traded with them—some said for slaves. It was rumored they’d established outposts or a colony in territory the Dominion claimed but didn’t inhabit, up in the “Californias,” and the Doms had spent years building a massive force called “La Gran Cruzada” to expel them. That was probably the only reason they hadn’t sent more troops here.

“Damned Brits’re always stirrin’ things up wherever they are, even here,” Holland groused, then hesitated, thinking aloud, “I guess the Doms could bring more ships ’round the Horn if we raise too much fuss.”

Varaa blinked rapidly, thinking hard, eyes narrowed. “I don’t think so. When my people came here twenty years ago—Mi-Anakka,” she stressed, as opposed to her Ocelomeh, “we surveyed the coast as best we could. Exploration was our purpose, after all.” She bowed slightly to Sira Periz. “I assure you the coastlines we contributed to the embroidered atlas in the map room of the Audience Hall in Uxmal are correct. We missed places,” she confessed, glancing at Holland and blinking curiosity, “a long stretch to the south of what you call the ‘Mosquito Kingdom,’ in fact.” She shook her head. “But we started as far south as possible. There is no passage around the ‘Horn.’ It’s entirely choked with ice.”

Anson shrugged as if none of that mattered. To him, it didn’t. “So there’s Brits in the Pacific. Good. If so, they’ve helped us this time whether they meant to or not. Remember what Don Frutos said about not givin’ much of a damn about us right now, with somebody else pesterin’ ’em somewhere else?” He nodded at Varaa. “Goes along with the rumors your people picked up, about most of the Dom army bein’ drawn northwest.”

“Which makes this the best possible time for us to press them here,” Sira Periz insisted. “Destroy them,” she added hotly, “so the shadow of the horror they bring no longer lingers over us!”

Lewis smiled at her again. “Oh, I agree entirely, though I don’t think we’ll do it here, exactly.”

Sira was taken aback. So were most of the others. “Before I go on, let me ask a few questions,” Lewis said to Sira. “First of all, can you tell me how negotiations are going to form a true Union of all the city-states on the Yucatán? We all agreed it’s essential,” he pressed.

Sira and Samantha both looked troubled. “We did and do,” Sira confirmed, “but others are . . . less sure.” She sighed. “I fear little has changed since our earlier efforts except I and King Har-Kaaska are now convinced as well. So are Alcalde Truro of Itzincab, Alcalde Ortiz of Pidra Blanca, even Alcaldesa Yolotli of Techon. All the leaders of the biggest cities. But the ‘how’ and ‘to what extent’ we’ll unite remains undecided, so many smaller towns and cities stand and wait,” she ended sadly. “They send supplies and volunteers to join us—all know what is necessary, that we must work together—but this ‘Union’ is too strange to them, too much like, pardon me,” she apologized, “surrendering themselves to become one with the Dominion.”

Leonor snorted. “Big difference is we won’t kill ’em for not joinin’, but the Doms’ll kill ’em whether they do or not.”

“And that’s part of the problem, my dear,” Samantha said. “Many of their leading citizens blame us for stirring the Doms against them!”

“Nonsense, of course,” Father Orno assured, speaking for the first time. “The Doms would’ve had us already, just using the Holcanos, if God hadn’t brought you here.”

Captain Anson shook his head. Like Lewis, he was always uncomfortable with the idea that God—quite traumatically, in fact—brought them all here just to fight the Doms. Harkin an’ Orno are convinced, an’ so are a lot of the men, he thought. Lewis never discourages the notion an’ I wonder if he believes it himself, deep down? He supposed it was easier to accept everything that’d happened to them if they thought there was a purpose behind it. “So where does that leave us?” he asked.

“Officially, essentially where we were,” Sira confessed, “but unofficially, things are much closer than that. Uxmal, Techon, Pidra Blanca, and Itzincab—I’ll include King Har-Kaaska and his Ocelomeh—remain independent, but as firmly allied as it’s possible to be.”

“Rather like your various states under the ‘Articles of Confederation,’ ” Samantha supplied helpfully.

“That didn’t work very well,” Lewis reminded her.

Sira Periz shook her head. “Whatever that was, we’re integrating our economies and everything we make, beyond what our people must have for themselves, to support the army”—she threw Holland a smile—“and navy.” She looked back at Lewis. “All under your direction, Major Cayce. Even King Har-Kaaska will obey your commands.”

“How do you keep all that sorted out?” Anson asked skeptically.

“As originally envisioned, Colonel De Russy mediates disputes between us and advises us what the Allied Quartermaster’s Department under Mr. Finlay and Procurador Samarez requires, who must supply it, where it must go, how it will get there and who will use it.”

“Watch that little villain Finlay.” Holland chuckled. “Wasn’t above linin’ his pockets when he was my purser in Mary Riggs.”

“He and Procurador Samerez both, then,” Sira Periz said dryly, “but there’s no evidence they’re doing it now.”

“Not while their lives are on the line,” Holland said, nodding. “Both were made for the job an’ neither wanted it. It’s that or fight, though, an’ die if we lose. I reckon they’ll do fine till the war’s over.” He laughed. “After that, you better fire ’em both.”

“The whole thing’s working rather well,” Samantha assured hopefully. “De Russy presides as manager over the Council of Alcaldes and makes final decisions. He can be outvoted,” she admitted, “but it hasn’t happened yet.”

Lewis grunted, obviously less than pleased. Everyone knew he wanted a truly united nation, a “new United States” and rock-steady cause for his army to fight for. But the army was already united. It knew the stakes, and its cause was survival and freedom. He’d united it into a single, integrated force, already fighting for the cause he envisioned, whether its provincial leaders understood it or not. And after he led it to victory over the Doms at the Washboard—something no one ever imagined—Lewis Cayce would’ve been amazed, possibly horrified, to learn the army would go anywhere and fight anyone—for him.

“Does this affect your planning?” Sira Periz asked anxiously.

“Yes,” Lewis murmured absently. “Well, no, not really. As you say, with Agon on his heels and most of the rest of the Dom army with this Gran Cruzada and heading as far away from us as it can go, we’ve a brief opportunity to beat the enemy soundly and decisively. We have to seize it.” He looked at her. “Perhaps clear away that ‘shadow’ you spoke of forever. What’s the strength of the Home Guard now?” he asked as if changing the subject. “And the Pidra Blanca Home Guard as well?”

Sira raised her eyebrows. “Guard losses at the Washboard weren’t severe, but they were heavily depleted by transfers to line regiments that did suffer badly, to bring them up to strength. Particularly the 1st Uxmal and 3rd Pennsylvania,” she added somberly. “But the victory has boosted enlistment to the point that I don’t think we’ll have to resort to conscription. At least not right away.”

That was good news. Lewis hated the very idea of conscription, almost as much as he hated slavery. Ironically, slavery was as deeply entrenched on this world as the one he’d left, but it didn’t have the impossible (for him)-to-defend racial component prevailing in his homeland—and his native state of Tennessee. Only captive enemy warriors—mostly Holcanos—were forced to labor by the Allied cities on the Yucatán, and having seen the savage aftermath of battle with that hated foe, he had to confess that well-fed servitude was more humane than slaughtering them all. Far more humane than what the Holcanos—and Doms—mean to do to every living soul in this land, he grimly rationalized. He still didn’t like it. It had too much of the sense of Imperial Rome to suit his Whiggish leanings, but the only way to change it was to win.

Sira Periz was still talking. “And Major Wagley—much improved from his wound, by the way,” she inserted a little smugly, knowing no one had expected the young Pennsylvanian to live, “is finding the new recruits more enthusiastic and willing to learn. As of now, the Home Guard at Uxmal stands at fifteen thousand including support—at various levels of readiness, of course—and a thousand are armed with captured Dom muskets. I’d ask for more of those, but I know it takes time to make the necessary alterations and most must go to ‘line’ units until we can make our own weapons.” (As issued, Dom muskets were bulky and crude but reliable enough. The biggest deficiency was that their bore diameters ranged wildly from roughly .72 to .76 caliber, so the “standard” Dom ball was about .70 caliber and rattled erratically down the barrel when the weapon was fired, making it ridiculously inaccurate. All were being reamed true to .77 caliber, to fire a larger standard ball for better accuracy. Blacksmiths were also reforging the thousands of plug-style bayonets they’d recovered and fitting them with tubular sockets that could be fitted on the outside of the barrel, allowing soldiers to keep shooting with the blade affixed.)

“Even horse recruitment is up, in addition to the seventeen hundred sound Dom animals collected after the battle,” Sira continued, “but I credit a new enthusiasm for the cause more than anything. Their owners no longer hide them. Loose or wild horses are getting harder to find.”

Horses were indigenous to the Americas on this world, though they looked a little . . . odd. Generally shorter but broader and more powerful, they were usually tan or brown with dark contrasting stripes. The problem was, “this” Yucatán was covered by dense forest, and its people largely relied on smaller or much larger animals like burros or armabueys (basically two-ton armadillos) to haul burdens from place to place. Wild horses were rare in the forest, hard to catch, and extremely difficult to protect from predators after all the effort to domesticate them. Doms had plenty of horses, mostly bred from those their seventeenth-century ancestors brought, yet were happy to rely on placid, plodding armabueys to draw their army’s guns and other heavy burdens. Lewis was convinced that only mobility gave them a chance in this war, and he demanded horses.

“As for the Pidra Blanca Guard, four thousand men, armed and trained with pikes, are marching from there to Uxmal now,” Sira ended triumphantly. “These numbers don’t count recruits from Uxmal, Pidra Blanca, and Techon already training for line regiments as well.”

Lewis frowned. “Too many able-bodied men taken from fields and factories could kill us as quickly as not enough troops,” he warned. The “Powder Monks” had established a great gunpowder factory on the banks of the Cipactli River, and a number of rotary tool machine shops had been built as well, supervised largely by Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Tennessee gunsmiths, blacksmiths from everywhere, and other men from the ranks who’d worked in such places before joining the army on another world. Still near the beginning of the “dry season,” when it only rained once or twice a week but the Cipactli still ran high, they were making a lot of good gunpowder in the new mill, but the gunsmiths (and their numerous apprentices) were repairing, reaming, and sometimes shortening almost nine thousand captured muskets. The mines and foundries near Itzincab had been reopened, and smelters were casting copper roundshot, canister balls, and lead projectiles for rifles and muskets at a fantastic rate, sending much of it downriver on flatboats. Gun carriages, limbers, caissons, forge wagons, battery wagons—all were being made to precise plans taken directly from the manual, Instruction for Field Artillery Horse and Foot—1845, that Lewis had provided. Copies were made on improved paper (also good for making musket cartridges), and Colonel Ruberdeau De Russy and Major Andrew Reed had between them produced all three volumes of Scott’s Tactics. Those manuals together had just about everything anyone needed to know about training and equipping a modern army, and even how to use it—to a degree.

“I can’t stop them from volunteering for the guards or line regiments,” Sira said a little wistfully. “Not when you need them so badly. I can make sure they train their replacements, and those replacements are available. People are swarming into the cities, often from those very towns and settlements not yet committed to the cause. Women”—she frowned, glancing at Leonor and Varaa—“whom you won’t allow in the army, already outnumber men in the factories and shops. The very old and young are joining them now. You’ll have all the troops and supplies we can give you,” she added a little haughtily, “but what will you do with them?”

Lewis pursed his lips. “You need to keep five thousand guards in Uxmal to man the defenses in case the Doms try something from the sea, and to protect the people and production facilities from agents of the enemy.” They’d already had trouble of that sort. “I want the other ten thousand, plus the four thousand Pidra Blanca Guards here at Nautla, manning these guns and fortifications. Their primary purpose, at first, is to convince Don Frutos and General Agon our whole army is here. Hopefully, they won’t have much to do but continue to drill and train.”

“The rest of the army won’t be here?”

“No.”

“That’s a lot of troops just putting on a show,” Harkin grumbled. “More than we had in the whole army at the Washboard.”

“Yes,” Lewis agreed, “the force we leave must be strong enough to fool Agon, but the guards won’t just be for that. Like I said, they still need training, and pikes are better for defense than attack. They will have to defend Nautla if Agon mounts an assault.” He paused. “And I’ll need them for other things . . . when they’re ready.”

“So you are planning an attack of your own,” Sira said, sounding a little confused. “But where?”

Instead of answering directly, Lewis gave the alcaldesa a reassuring grin, then looked at Captain Holland. “What’s your opinion of the Dom transport galleons you captured? Are they fit for sea?”

Holland squinted, contemplating his response. “Aye, they weren’t damaged, but they’re shameful slow—an’ dismal slugs beatin’ into a wind. Freeboard’s so high aft, they’re the very devil ta tack an’ the prize crews—fine sailors—missed stays bringin’ ’em in. Thought we’d lose the masts outa one when she was taken aback.” He fumed. “Damn things got less for forestays than any ship I ever seen. Don’t even use staysails!”

“Can you alter the rig in any way—that wouldn’t be too noticeable—to make them faster? Handle better?”

Holland chuckled mischievously. “If they was dismasted in a storm, I could jury-rig a better mast an’ sail plan!”

Everyone laughed appreciatively at the sailor’s confidence, but Lewis shook his head. “But would it be a rig the Doms would know? Best leave things as they are otherwise. In any event, I want you to take one of the prizes and have a look at Vera Cruz yourself. Tiger will accompany you, but stay out of sight.” He paused, then pressed. “Your First Lieutenant, Mr. Semmes, he can handle her in your absence? Be counted on to take whatever action is necessary?”

Holland raised a brow. “Sounds to me like ‘havin’ a look’ is the least you want, but aye, Billy Semmes is a good ’un for a Britisher. His old skipper left his guts a little sour, but he’s perked right up.” He considered. “I’ll take Mr. Sessions with me in the slug. He ain’t as good a seaman as Semmes, but was a privateersman once an’ knows how ta use a cutlass.”

Lewis held up a hand. “Obviously, I do want you to recapture Isidra, but only if it can be done with almost no risk. I’ve told you before, Captain Holland; we can’t spare you. Nor can we spare Tiger.”

Holland grinned. “An’ I replied that I can’t spare me neither. I’ll get Isidra out for you, an’ I’ll be careful too.”

Lewis nodded, then looked back at Sira Periz. “As for the army and the offensive I have in mind, whether the Blood Cardinal Don Frutos remains in overall command or not, I expect General Agon will be strongly reinforced in fairly short order.”

“If they let him live,” Anson inserted.

Lewis bowed his head. “True. We’ve all seen how little tolerance the enemy has for failure. But until our scouts tell us more, we’ll proceed as if the enemy can’t be stupid enough to execute the only commander they have who knows anything about us. That means we have to assume he’ll fortify Campeche and have plenty of troops if we march down there.”

“An attack there would be mighty tough,” Leonor said. “We got a lot o’ new troops ourselves, an’ even our ‘veterans’ only been in one big fight. They did good,” she conceded, “but throwin’ ’em against a well-defended position would be bloody as hell.” That was a long speech for Leonor in a discussion like this, but she, her father, Varaa, Hudgens, and probably Corporal Willis were the only ones who already knew what was cooking in Lewis’s mind.

Lewis was nodding, looking steadily at Sira Periz. “Exactly what I’ve been thinking,” he agreed, then added in a matter-of-fact tone, “so we’ll rely on the local knowledge of Captain Anson’s Rangers, dragoons, and lancers, and Varaa’s Ocelomeh scouts, to find a way around General Agon.”

There was silence for a moment until surprise overwhelmed the short, dark-haired, barrel-chested Captain Marvin Beck, commanding the 1st US Infantry. “You’d leave him in our rear?” he blurted. The other young infantry commanders shifted uneasily; Captain James Manley, in charge of the 1st Uxmal Infantry, Consul Koaar-Taak (the only other Mi-Anakka with the division) of the 1st Ocelomeh, and the newly promoted Captain John Ulrich, now leading the 3rd Pennsylvania with George Wagley gone. All trusted Lewis, but with Major Reed away in Uxmal, they felt a little adrift. Beck was the senior infantryman present—he’d been promoted an hour before the others—and probably considered it his duty to speak.

“I suppose he would be behind us eventually,” Lewis conceded, then added vaguely, “but he won’t be astride our line of supply.”

Varaa clapped her hands, blue eyes bright. “It’s a lovely plan,” she exclaimed with a grin, tail whipping. “Lewis and I have always thought alike, you know.” She kakked a laugh at the questioning looks. “And if you don’t see it—you who already know us so well—I’m sure General Agon won’t. After we take a rather lengthy stroll and help Har-Kaaska—and Major Reed when he joins him—finish our business with the Holcanos once and for all, First and Second Divisions”—she blinked amusement at Holland—“and our gallant little navy, of course, will end up astride the enemy’s line of supply. And fourteen thousand highly motivated—and better trained by then—Home Guard troops will be in General Agon’s rear!”

Lewis’s expression turned somber. “That’s the size of it. It won’t be easy, and we’ll have to move with care not only to elude the enemy’s attention but to avoid—or deal with—the many monsters we’ll encounter.” He was looking at the dense, gloomy forest to the southeast. “About three hundred miles, I should think.”

“Through that?” Captain Ulrich almost squeaked. The big former sergeant had a deep voice, and no one would’ve imagined he could make such a sound. He didn’t either and continued more normally, embarrassed, “It’s swarming with man-eating boogers, and there’s not even roads!”

“But there are,” Consul Koaar countered thoughtfully. “Nothing like the Camino Militar,” he conceded, “and they’ll be difficult to negotiate with artillery, but my people know them.” His eyes narrowed. “As do the Holcanos. After King Har-Kaaska finishes with those still around Itzincab, he’ll press on toward Puebla Arboras.”

Anson was nodding. “Drive ’em out of there an’ there’ll be nowhere for ’em to go but Cayal. We’ll meet Har-Kaaska an’ Major Reed there. Finish the Holcanos for good.”

Consul Koaar blinked at Anson and grinned. “None must get past us to warn General Agon. Your Rangers will be very busy, Captain Anson.”

Anson grinned back. “You too.”

Samantha Wilde fluttered her fan. “There’s that ‘Captain’ again. ‘Captain, captain, captain!’ ‘Captains’ everywhere now. Don’t you all find it remarkably tedious? And all to keep from stepping on Colonel De Russy’s toes! How absurd, and how do you keep it all straight?”

De Russy had come to this world in command of the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. Appointed by the governor, he was a politician, not a soldier. Sadly, but fortunately, he recognized that early on. He wasn’t a coward, but wasn’t a leader either, so he put Lewis in charge until he was “fit” to take over. That would never happen. He did have a politician’s gift for coercing compromise, however, and was perfect for his role as “Manager” of the Council of Alcaldes.

Samantha looked sternly at Lewis. “Colonel De Russy has decided you must accept a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel. Andrew Reed will as well, though you’ll retain a few moments’ ‘seniority.’ ” She chuckled. “Now at least everyone can call you ‘colonel’ and you can spread a few more ‘majors’ around. Surely there’ll be less confusion.”

“None of us are confused about who leads us,” Consul Koaar pronounced.

Alcaldesa Sira Periz cleared her throat with an apologetic look and admitted in a small, vulnerable voice that only those she trusted completely would ever hear. “I am, sometimes. I pray it is the One God who leads us, as Father Orno and Reverend Harkin insist”—she looked again at Lewis—“but whether He does or not, it’s up to you to do so on the battlefield, so I pray He guides your steps and your hand.”

Lewis took a long, deep breath. “I do too.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...