- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

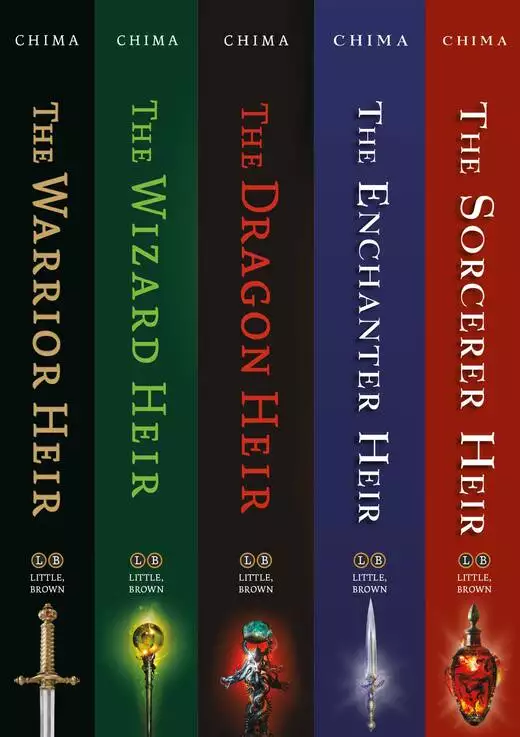

Read the complete Heir Chronicles in this omnibus edition! Three boys, three talismans, one destiny. In this page-turning collection featuring The Warrior Heir, T he Wizard Heir, The Dragon Heir, The Enchanter Heir, and The Sorcerer Heir, Cinda Williams Chima explores what it means to be different, what's worth fighting for, and what's worth dying for.... Dark forces are after a boy who is heir to a dangerous legacy. A girl grapples with evil within. A seventeen-year-old is a deadly assassin, and a wild child uncovers a mystery. The Wizards and Warriors, Seers, Enchanters, and Sorcerers must keep their fragile peace despite all that would break it. The answers they need lie buried in the tragedies of the past -- the question is whether they can survive long enough to unearth them.

Release date: May 26, 2020

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 2220

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Heir Chronicles: Books I-V

Cinda Williams Chima

June, 1870

The scent of wood smoke and roses always took him back there, to the boy he was and would never be again.

The Roses came for them during his tenth summer. In those days, Lee was slight of build, though his father always said his big hands and feet predicted height and broad shoulders when he was grown. He was the youngest, a little spoiled, the only one of four children to display the telltale signs of a wizard’s stone. His parents complained that it took him two days to do a day’s worth of work. Not lazy, exactly, but largely inefficient.

They had been back only a fortnight after a month on the run. It was a mistake to come back. Lee knew that, afterward, but his father was a farmer, and a farmer can’t afford to stay out of the fields too long during the growing season. Besides, the Roses’ previous attacks had been hit-or-miss affairs. They would sweep through the village on the river, search the outlying farms, and then disappear, sometimes for as long as a year.

Bandits, their neighbors called them, and speculated that they’d been soldiers in the recent War of the Rebellion. Only seven years before, Confederate General John Morgan had led his raiders through these southern Ohio hills.

Lee’s family knew better. Knew what these raiders were looking for, and why. The Roses had followed the lineages west from the port cities in the east. They hunted the descendants of the Silver Bear, harvesting the gifted for the Trade. His brother Jamie had been taken when Lee was just a baby, while they still lived in Pennsylvania. Jamie had been an enchanter. Lee didn’t really remember him, but they always burned a beeswax candle for him on the holidays.

Lee was just happy to be home, back in those green, blunted hills tailor-made for a dreamer. On that fateful day, he had left the house early in order to avoid any chores that might be assigned. He’d spent the morning on the riverbank, and the product of it was a stringer of catfish that he planned to offer up for supper. He ambled back along the road that led up to the house, just two wagon ruts, really, detouring whenever something caught his interest.

As he drew closer to home, he caught a strong scent of wood smoke. It was odd, because it was summertime and the stone fireplaces and woodstoves that heated the house had not been in use since April. Perhaps his father was clearing land or burning off brush. If so, Lee should have been home to help. From the angle of the sun, he knew he was already late for the midday meal. His mother would be in a fine state about it.

It was then that he saw a dark column of smoke climbing into the sky through the tops of the trees up ahead. From the location, he knew it must be coming from the home yard. Perhaps the kitchen had caught fire. He broke into a run, the fish swinging awkwardly at his side.

As it turned out, it was the kitchen, and the barn, and the garden shed. They were all ablaze, wood and thatch buildings ready-made for burning, and half devoured already. The main house, though, was stone, with a slate roof, and so more resistant. His father had teased the stones for it out of the surrounding hills. A fine house for that part of the world, and perhaps that was why it had drawn attention. Lee stood in the fringes of the forest, unsure what to do. The fish slid unnoticed from his fingers.

Why was no one fighting the fire, pumping water from the well, passing buckets, and soaking down the wood that had not yet caught? He scanned the yard. No one was there, not his father, nor his brother, not anyone.

Keeping within the shelter of the woods, he circled around to the back of the house, knowing the hedges and walls that quilted the gardens would give him cover. His father had come over from the Old World, and he was proud of those gardens. They were civilized, hemmed in by stone, like those in their family’s ancestral home.

Instinct told him to stay hidden. He crouched, fading into the shadow of the stone wall where it ran near the forest, following it back to the house. The skin on his face tightened from the heat of the kitchen fire as he slipped past it, through the vegetable garden, to the back door of the house. The door was standing partly ajar. He pushed it wide open.

It was a mess inside. Clearly, his family had been at the table when the attack came. Had he returned on time, he would have been among them. Food lay scattered, ground into the floor—bread and pieces of fruit and the small cinnamon tarts that Martin liked so well. The furniture had been chopped to pieces and set ablaze like kindling, tables were overturned, crockery shattered against the wall. Someone was either very angry or wanted to make a point. Lee circled around the shards of glass on the floor, aware of his bare feet.

He crept farther into the house, barely breathing, keeping flat to the wall, his ears straining for any clue that would tell him the intruders were still inside. As he moved toward the great hall, he became aware of a sound, a rhythmic banging. It grew louder as he drew closer to the front of the house. As he slid his hand along the wall, he encountered something wet. Bringing his hand close to his face, he caught the metallic scent of blood. Blood was splashed all over the floor and walls. Dark red puddles were congealing between the stones in the floor. His heart clamored in his chest; he had to fight to get his breath, but he forced himself to go on.

A body lay in the doorway to the hall, a man dressed too fine to be local, in a waistcoat and a silk shirt and cravat, not homespun, like Lee’s. He looked middle-aged, but was probably much older. A man who carried no obvious weapons, and needed none. A wizard, it must be.

Lee’s brother Martin lay facedown just beyond the doorway, his body nearly torn in two. Most of the blood must have been his. He was ten years older, big and broad shouldered, known as a hard worker. Practical. Not a dreamer like Lee. Anaweir: no magic in him, no match for wizards.

“Martin.” Lee’s lips formed the word, but he had no breath to make a sound.

Lee crept into the room, feeling the tacky blood under his toes. There were the bodies of two more wizards, and then he saw his father sprawled across the hearth, his legs in the fireplace as if he’d been thrown there.

His father, who told him stories of castles and manor houses across the ocean. Who could steal fire out of the air with his fingers and spin shields out of sunlight. Who called him wizard heir and had begun to teach him the charms that would shape magic to his use. Who had been powerful enough and smart enough to protect them from anything. Until now.

Lee fell to his knees retching, and lost what little remained of his breakfast. Then he heard the noise again, the banging sound.

His mother was huddled in her rocking chair next to the fireplace, her knitting on her lap. The sound he’d heard was the slam of the rocker against the wall. Now that he was closer, he could hear her knitting needles, clicking together in a businesslike fashion. But she had picked up no stitches. Although she had yarn in her basket, and on her lap, she was knitting nothing.

“Mama?” he whispered, drawing close to her, looking warily over his shoulder. “Was it the Roses?” She stared into the hearth where Papa lay cold and broken. Rocked, and knitted nothing, and said nothing. She didn’t have to. He knew it was the Roses; of course it was the Roses, who else would it be?

“Are you hurt, Mama?” he said again, a little louder. He wormed his hand into hers, but her fingers didn’t close around his, and in her eyes there was a dreadful nothing.

He fought back a sob. No crying. He was the man of the family now. “Where’s Carrie?” he asked. His sister was not among the bodies on the floor, which made sense because the Roses would want Carrie alive.

His mother didn’t answer. Carrie could be taken, or she could be hiding. If she were taken, they would head south toward the river, and then west to Cincinnati or east to Portsmouth, where they could catch a boat. If she had been taken, he didn’t know what he would do.

If she was hiding, he knew where she would be. He left the house the way he’d come in.

They called it the root cellar, but it was really a cave that tunneled into the side of a hill some distance from the yard. In that cool damp space they stored food: potatoes and turnips and carrots and dried beans and peas in sacks.

The mouth of the cave was covered with red climbing roses, and flat white and pink wild roses. They were all in bloom, their fragrance cloying. He parted the thorny canes and stepped inside.

“Carrie?” he said softly. “It’s me.”

For a moment, there was nothing, and then a rush of movement in the darkness, and his sister wound her arms around him, whispering, “Lee! Why did you come here? It’s too dangerous. You should have run away when you saw they’d come back.”

“Carrie, they killed Papa and Martin, and there’s something wrong with Mama, she won’t talk to me.” The words tumbled over each other, louder than he intended.

Carrie sucked in her breath and pulled him tight against her, so the rest of what he had to say was spoken into her shoulder. She murmured soothing words to him, but not for long. Her back straightened and her hands traveled down to his elbows.

“Listen to me now.” She held him out at arm’s length. She wore trousers and rough-woven shirt, her knife belted at her waist. Their mother hated to see Carrie dress like a man, but sometimes she did anyway. “You’re going to have to be very brave,” she said.

“Don’t worry,” he said, standing up a little straighter, trying to make his voice deeper like Martin’s. “Papa taught me how to protect you against the wizards.”

She swallowed hard. “Silly. You are a wizard. You are going to have to be brave enough to go for help.” He tried to interrupt, but she went on. “I want you to head straight south to the river and follow it to town. Stay under cover and away from the roads. When you see someone you know, tell them what happened and ask them to send help for Mama.”

“Aren’t you coming with me?” He felt lonely already. He tried not to think about Martin or his father, because he knew the tears would come again.

“I’m going away for a while,” she replied. “It’s too dangerous for me to stay with you and Mama. The Roses are looking for warriors. Not wizards or Anaweir. They’ll leave you alone if I’m not around.” Seeing his expression, she hurried on. “I’ll come back when it’s safe.”

Lee thought of his mother, silent and scary in the house. He knew it was wrong, but he didn’t want to go back there alone. “Take me with you, Carrie. Please.”

Carrie shook her head. She was practically an adult, yet tears were streaming down her cheeks. “You have to stay, Lee. Mama is Anaweir. She needs someone to look after her.”

“Oh, all right,” he said petulantly, not wanting her to know how frightened he was. He might as well get started, since he would be taking the long way to town. He raked the roses aside again, sticking himself in the process, and stepped out into the broken sunlight. And into the arms of the wizards who waited there.

“Carrie!” he screamed. Hands grabbed him, holding him tight, lifting him away from the mouth of the cave. He struggled and kicked, slamming his elbow into someone’s face, feeling the cartilage give way followed by the rush of hot blood. He twisted his body, but he couldn’t get free.

There were too many, a half dozen of them. Strangers with bearded faces, dressed for Sunday, like the dead wizard in the hall. Lee didn’t know any attack charms, really, but he could find fire, so he plucked it out of the air and sent it spiraling into the men around him. There was more cursing, and then they threw him to the ground.

The wizard with the bloody nose pointed at Lee, muttering a charm. An awful cold went through him, and he went limp. The wizard slid his hands under Lee’s arms, hauled him upright and held him there, his feet off the ground, dangling like a puppet.

“Call her out,” the bloody-nose wizard commanded, and flamed him with his hot hands. Lee’s muscles seized, and he screamed—he couldn’t help it—but then he clamped his mouth shut stubbornly.

“We haven’t got all day. The White Rose is right behind us.” The wizard released power into him again, like hot molten metal running into his veins, but Lee was ready this time. He sucked in his breath, but didn’t make a sound.

“Come out or we’ll snap the boy’s neck!” Bloody Nose shouted. The roses that obscured the mouth of the cave trembled, dropping petals as they were thrust aside. Carrie emerged into the sunlight in a half crouch, knife in hand. Seeing Lee in the hands of the wizards, she straightened and let the knife drop to the ground.

Bloody Nose gave Lee a triumphant shake. “You led us right to her.”

Carrie dropped to her knees, bowed her head. “Please, my lords. I’ll come with you. Only, let my brother go.”

Lee tried to speak, to tell Carrie to get up off her knees, that they would fight the wizards together. “Carrie, don’t….” His protest became a scream of pain as Bloody Nose sent flames into him.

“Wylie. Enough.” This from a gray-haired wizard with a seamed face, seemed to be in charge. “Bring the reader.”

Wylie tossed Lee aside as though he weighed nothing, then fumbled in a pouch at his waist. He produced a silver cone and handed it to the leader. Two wizards moved to either side of Carrie, grasping her arms and lifting her to her feet. The leader yanked her shirt free of her trousers and thrust the cone up against the skin of her chest. Carrie flinched, but looked to one side and said nothing. After a moment, he nodded and withdrew his hand.

“There is a warrior stone,” he said in an Old World accent. Satisfied, he returned the cone to Wylie. “God knows, we’ve paid a price for it. Let’s get her out of here before the White Rose catches up to us.”

The wizards brought their horses forward and began to mount up while their leader bound Carrie’s hands in front of her with a silver chain.

Wylie slammed Lee down against the trunk of a dead tree. The wizard knelt beside him, pushed his chin back, and placed his fingertips against his throat. Lee looked into the flat gray eyes and knew he was about to die.

The leader noticed. “Let the boy be, Wylie,” he said gruffly, pulling on his riding gloves.

Wylie looked up. “He’s a witness. We killed a wizard, and if word of that gets back to the council…”

“There’s three dead on our side as well,” the leader pointed out. “If the boy’s father had stayed with his own kind, he’d still be alive. This is a child. Let’s not make matters worse.”

“You’re not the one who did the killing. This one may be a wizard, but he’s of mixed blood.” Wylie’s lips tightened in disgust. “Wizards, warriors, sorcerers, even Anaweir comingling as equals. It’s unnatural.”

“Perhaps they’re on to something.” The leader gestured toward Carrie. “At least the girl’s healthy. Which is more than I can say for the warriors at home.”

Wylie’s fingers still pressed against Lee’s throat. Lee could feel the power in them, a faint vibration against his skin.

“I told you to leave him be,” the leader said. “We’ve lingered too long already.”

Wylie finally stood and moved away, looking for his mount.

Carrie had been lifted onto one of the horses. She stared straight ahead, her mouth in a tight line, spots of bright color in her cheeks. The leader took the reins of her horse and then mounted his own. He pointed at Lee, disabling the charm that had been laid on him, but Lee just lay there, afraid to move, knowing finally and for true that he was, at heart, a coward.

And then it happened. A bolt of light blazed through the trees, blue-white and deadly, trailing flaming stars—like the fireworks Lee had seen once in Cincinnati. The air crackled with electricity, and even at a distance, his hair stood on end. The blast struck its target dead-on, and for a moment, Carrie and the horse beneath her were outlined in flames, like some heavenly bodies that had passed before the sun. There was a shimmer in the air, a kind of visual vibration, and then they were gone, horse and rider vaporized, as if they had never existed.

“It’s the White Rose!” one of the wizards shouted.

Turning his horse, he charged through the trees. The other wizards wheeled their horses and followed, screaming in rage, but the White Rose had done what it came to do, and was in full retreat. In a matter of minutes, the horses and riders were gone. Dust settled slowly through shafts of sunlight, and the clearing was quiet, save the sound of the wind moving the branches overhead.

By the time darkness had fallen, Lee was already miles away, sitting cross-legged on the riverbank. When the moon finally cleared the trees, it shone on the Ohio, which ran like a silver ribbon in both directions. Across the river lay Kentucky, a mysterious darkness pierced by the lights of scattered settlements.

“I won’t be a bear any longer,” he said to himself. He would be fiercer, more invincible. “From now on, I’m a dragon.”

Before he continued on, he took his sister’s knife and wrote something in the soft mud at the water’s edge, wrote it in order to fix it in his mind.

The word was “Wylie.”

TRINITY, OHIO

More than 100 years later

The baby awakened when Jessamine uncovered him. She thought he might cry, but he only gazed at her solemnly with bright blue eyes while she opened his shirt and examined the incision. Still a little red and puffy at the edges, but no sign of infection. Perfect. She’d half expected that the procedure would kill him, but he seemed to be thriving. Only a month post-op, her patient had gained weight, his color was good, pulse and respiration normal.

No reason he couldn’t travel. None at all.

She snapped the baby’s shirt closed, feeling pleased with herself. Those fools at the hospital had been difficult about everything: her methods, that she’d brought her own people to assist, that she wouldn’t let them observe the procedure.

Idiots. Perhaps she should have allowed a few of them into the operating theater. It might have been worth it to see their faces before she wiped their minds clean.

Of course, it would be years before she would see how the experiment played out. Considerable time invested if it failed, but much to be gained if it succeeded. Perhaps an end to the shortage of warriors. An unlimited supply of fodder for the Game. Final victory to the White Rose.

She glanced around the nursery. It was full of baby things, more paraphernalia than she could possibly carry. She could always buy more when they reached their destination. What would a baby need to travel? Diapers and clothes. A seat to travel in. What would he eat? Formula? She shrugged. Pediatrics was not her specialty.

She found a large bag on the floor of the closet that already held diapers and a box of wipes. No bottles, though. She yanked open a dresser drawer and found layers of tiny clothes. She shoved some of the clothes into the bag, which was decorated with elephants and giraffes in primary colors. Jessamine frowned and ran her hands over her elegant suit, swept a curtain of dark hair away from her face. She did not relish the idea of walking around with a diaper bag on her shoulder and a baby on her hip. She should have hired someone to take charge of the brat from the start.

She pulled a plastic infant seat from the closet and set it on the floor next to the crib. The catch resisted when she tried to lower the side, so she stretched over awkwardly and scooped the baby from the mattress. She laid him in the seat and began fussing with the straps.

How does one go about finding a nanny? She had no idea.

“What are you doing here?”

Jessamine jumped. The enchanter Linda Downey stood in the doorway. She was just a child, really, barefoot, in jeans and a T-shirt. Linda was the baby’s aunt, Jessamine recalled, not his Anaweir mother. Good. Not that it would have mattered, but she preferred to avoid a scene.

Jessamine stood, leaving the baby in the seat and the straps in a tangle. “I didn’t know anyone was home,” she said, instead of answering the question.

Linda tilted her head. She was a pretty thing, with long dark hair woven into a thick braid. She moved with a careless grace that Jessamine envied. But then, if Jess had to choose one gift over another, she would always choose her own.

“Of course there’s someone home,” the girl said, in the insolent way of teenagers. “You don’t leave a baby by itself.”

At least the sudden and awkward appearance of the enchanter solved one problem. “I’m glad you’re here,” Jessamine said imperiously, with a sweep of her elegant hand. “I need you to pack up some things for him, enough for a few days, anyway. Food, clothes, and so forth.”

“Why? Where do you think you’re taking him?”

Jessamine sighed, flexed her fingers with their long, painted nails. “If you must know, I’m taking him back with me.”

“What?” It came out almost as a shriek, and the baby threw out its arms, startled. Linda took a step forward. “What do you mean?”

“I’m taking him back to England with me. Don’t worry,” she added. “He’ll be well cared for. I just can’t afford to leave him lying about.”

“What are you talking about?” Linda demanded.

“Since the surgery, he has…appreciated in value,” Jessamine said calmly.

Linda knelt by the car seat, looking the boy over as if she could discover something through close examination. She extended a finger, and the baby grabbed on to it. She looked up at Jessamine. “What did you do to him?”

“He needed a stone, and I gave him one. A miracle. Something no one has ever done before. I saved his life.” She smiled, turning her palms upward. “Only, now he’s Weirlind.”

“A warrior?” It came out as a whisper. “No! I told you! He’s a wizard. He needed a wizard’s stone.” Linda shook her head as she said it, as if by denying it she could change things. “It’s all in his Weirbook. He’s a wizard,” she repeated bleakly.

Jessamine smiled. “Not anymore, if he ever was.

Be reasonable. A wizard’s stone is hard to come by. Wizards live almost forever. But warriors…warriors die young, don’t they?” The last part was intentionally cruel.

Now the enchanter stood, her hands balled into fists. “I should have known better than to trust a wizard.”

Jessamine drew herself up. She was losing patience with this scrap of a girl. “You didn’t have much of a choice, did you? If it weren’t for me, he’d be dead by now. I’m not in the business of providing charity care. I did it because I intend to play him in the Game. And I think you’d better remember to whom you are speaking and hope I don’t lose my temper.”

Linda took a deep breath, let it out with a shudder. “What am I supposed to tell Becka?”

“I don’t care what you tell her. Tell her it died.” The Anaweir and what they thought were of no consequence.

“But why do you have to take him now? He can’t play in a tournament until he’s grown.” The girl’s voice softened, grew persuasive. Jessamine felt a gentle pressure, the touch of the enchanter’s power. “He’s alive, but how do you know he’ll manifest? And what will you do with him in the meantime?”

Jessamine shrugged. “Perhaps I’ll bring you along to watch him,” she said. “In a year or two you can go to the Trade.” The girl would bring a pretty price, too, if Jess was any judge. Enchanters and warriors were both hard to come by.

Linda took a step back. “You wouldn’t!”

“Then don’t try your enchanter’s tricks with me.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time on him already. I intend to keep an eye on my investment while he’s growing up.”

“If he grows up. If someone else doesn’t get to him first.” Linda extended her hands in appeal. “Everyone knows you are Procurer of Warriors for the White Rose. How long do you think he’ll last if he’s with you?”

The girl had a point. The stone Jess had used on the boy had come from a seventeen-year-old warrior, her last prospect. A girl who would never play in a tournament. She’d been butchered by agents of the Red Rose when they’d been unable to steal her away. Illegal, but then rules relating to the Anawizard Weir were made to be broken. “I assume you have a suggestion?”

“Let his parents raise him. Come back and get him later.”

The baby scrunched up his eyes and let out a screech, his face turning an angry blue-red. Unfathomable creatures, babies, Jessamine thought. Unfathomable and unpredictable and messy.

“He might be hard to handle later on if he’s not raised to it.” Jessamine said.

Linda lifted her eyebrows. “You’re saying a wizard can’t manage a warrior?”

Jessamine nodded, conceding the point. “What if someone else takes him to play?”

“In Trinity? No one will ever look for him here. It’s perfect. You’re a healer-surgeon. Suppress him, so he won’t stand out.” Linda sat down next to the baby, smoothing down his fringe of red-gold hair. “You can easily keep watch on him. His parents are Anaweir. They can be managed well enough. Tell them you need to see him on a regular basis. Becka will do whatever you ask. You saved her son’s life.”

Jessamine had to admit, the enchanter’s suggestion was appealing. It would be years before this boy could be put to use, and he would be nothing but trouble in the meantime. This way, she could keep the warrior brat out of harm’s way and out of her hair until he was old enough for training.

She looked into the enchanter’s blue and gold eyes. “What about you? Are you manageable? Are you going to be able to give him up when the time comes?”

Linda looked down at the baby. “As you said, I don’t have much choice, do I?”

“Jack!”

His mother’s voice cut into his dreams and he reluctantly opened his eyes. It was late, he could tell. The light had lost that early-morning watercolor quality and streamed boldly through the window. He’d stayed up too late the night before, stargazing. It was the night of the new moon, and some of the key constellations hadn’t slid over the horizon until after midnight.

“Coming!” he shouted. “Almost ready!” he lied as his feet hit the wood floor. His jeans lay in a heap next to the bed, where he’d stepped out of them the night before. He jerked them on, pulled a fresh T-shirt from the drawer, and threw a pair of socks over his shoulder.

Jack careened around the corner into the bathroom. No time for a shower. He washed his face, wet his fingers and ran them through his hair.

“Jack!” His mother’s voice had a warning note.

Jack leaped down the back stairs and into the kitchen.

His mom had granola and orange juice waiting for him. She must have been distracted, because she had also poured him a cup of coffee. She’d left her muesli unfinished and was sorting through a stack of papers.

That was Becka. His mother was a woman of a thousand passions. Although she had a PhD in medieval literature and a law degree, she had difficulty managing the household economy: things like school schedules, lunch money, and getting the library books back on time. Jack had taken on the task of organizing both himself and his mother from an early age.

Becka looked at her watch and groaned. “I’ve got to get dressed! I’m supposed to be at a meeting in an hour.” She shoved a large blue bottle across the table toward him. “Don’t forget to take your medicine.” She thrust her papers into a large portfolio. “I’ll be at the library all morning and in court this afternoon.”

“Don’t forget I have soccer tryouts after school,” Jack said. “In case you get home first.” His mother was a worrier. She always said it was because he’d almost died when he was a baby. Personally, Jack thought such things were hardwired. Some people always worried, others never did. He supposed his father fell into the latter category. Maybe it was hard to worry from three states away.

“Soccer tryouts,” Becka repeated solemnly, as if to fix it in her mind. Then she raced up the stairs.

Someone pounded at the side door. Jack looked up, surprised. “Hey, Will. You’re early.”

It was Will Childers, stooping to peer through the screen. Although Jack was tall, Will towered over him, and he was built solidly enough to play tackle on the varsity football team. His trumpet case looked like a toy next to him. “Jack! We gotta move! We’ve got jazz band practice this morning for the concert next week.”

Jack slapped his forehead and carried his cereal bowl to the sink. Pushing his feet into his shoes without untying them, he grabbed the book bag waiting by the door. Fortunately his saxophone was at school. “School starts early enough in the day as it is,” he grumbled as he followed Will down the street at a trot.

They cut across the grassy square and threaded their way between the classic sandstone buildings of the college. Trinity was a postcard Midwest college town; its streets lined with stately Victorian homes and ancient oaks and maples. Full of people who could recite every sin Jack had ever committed. He’d lived there all his life.

Thanks to Will, they were only a few minutes late for practice. It wasn’t until Jack was seated in homeroom and the firs

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...