- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

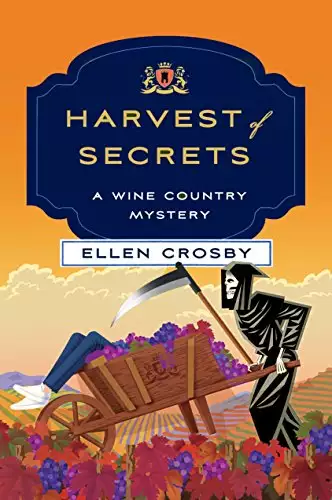

Synopsis

The search for the killer of an aristocratic French winemaker who was Lucie Montgomery's first crush and the discovery of dark family secrets put Lucie on a collision course with a murderer.

It's harvest season at Montgomery Estate Vineyard—the busiest time of year for winemakers in Atoka, Virginia. A skull is unearthed near Lucie Montgomery's family cemetery, and the discovery of the bones coincides with the arrival of handsome, wealthy aristocrat Jean-Claude de Marignac. He's come to be the head winemaker at neighboring La Vigne Cellars, but he's no stranger to Lucie—he was her first crush twenty years ago when she spent a summer in France.

Not long after his arrival, Jean-Claude is found dead, and while there is no shortage of suspects who are angry or jealous of his ego and overbearing ways, suspicion falls on Miguel Otero, an immigrant worker at La Vigne, who recently quarreled with Jean-Claude. When Miguel disappears, Lucie receives an ultimatum from her own employees: prove Miguel's innocence or none of the immigrant community will work for her during the harvest. As Lucie hunts for Jean-Claude's killer and continues to search for the identity of the skeleton abandoned in the cemetery, she is blindsided by a decades-old secret that shatters everything she thought she knew about her family. Now facing a wrenching emotional choice, Lucie must decide whether it's finally time to tell the truth and hurt those she loves the most, or keep silent and let past secrets remain dead and buried.

Release date: November 6, 2018

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Harvest of Secrets

Ellen Crosby

“You found a human skull?” I said to Antonio. “Just the skull?”

“It turned up when we had to dig up part of the tree root,” he said.

“Why were you digging?” I was irked, hot, and tired, and Antonio knew it. All he and Jesús were supposed to do was cut up the branches of a tulip poplar that had split in two after lightning struck it during a storm the other day and tote everything away. The tree, which had been at least five feet in diameter and probably seventy or eighty feet tall, had come crashing down onto the old brick cemetery wall. It had also taken out the roof and one side of an old fieldstone storage shed.

The storm, with its lashing rain and fierce wind, had been a warm-up act to Lolita, a Category 5 hurricane with a beguiling name and enough scary “worst-ever” attributes hung on it like ornaments on a Christmas tree to prompt mass evacuations in the Caribbean in anticipation of her arrival. Forecasters predicted Lolita would eventually come roaring up the Atlantic coast and barrel through Virginia, scaring the bejesus out of anyone in her path and making everyone at my vineyard more tense and edgy than usual at harvest time.

“We had to dig.” He sounded testy as well. “You’ll see why when you get here.”

Antonio gets prickly when he thinks I’m telling him how to do his job, or if I seem to doubt his word, though he is always respectful. Still, he has some cause to be annoyed because most of the time when it comes to running the vineyard or taking care of our equipment, he’s dead-bang right. He’s also one of the best and smartest farm managers I’ve ever known.

The Montgomery family cemetery sits on a bluff where it commands a breathtaking view of the Blue Ridge Mountains—especially at sunset—which is the reason my ancestor Hamish Montgomery, who received our land as a grant for his service in the French and Indian War, chose that site. Generations of my family have been laid to rest there since the late 1700s. Both of my parents were buried inside the low redbrick walls along with Hamish, and I had no doubt someday I’d join them.

“I’m on my way,” I said to Antonio. “In the meantime, don’t do anything or move anything, okay? Are you sure the skull doesn’t belong to one of the graves? Are you sure it’s human?”

“Don’t worry, Lucita. Jesús won’t go near it.” He spoke as if he were calming an upset toddler, instead of his boss. “He says it’s mala suerte—bad luck. Finding a skull means someone’s going to die. I’m sure it didn’t come from the cemetery and yes, I’m sure it’s human.” He added in that placating tone, “You’ll see.”

“Tell Jesús no one’s going to die. That’s just an old superstition.” I didn’t mean to snap at him, but just now I couldn’t afford to have either of them—or any of our crew—get spooked. Not in the middle of harvest, our busiest time of year.

But as I spoke a gust of wind rushed past me, icy fingers caressing my neck and making me shiver. My grandmother, my father’s mother, used to tell me that was the sign a soul was leaving this world on its way to the next.

Now I was imagining things. It was probably only a stray blast of cold air from the air-conditioning.

Antonio muttered something ominous-sounding under his breath and then hung up. All I caught was the word boda. Wedding. He and Valeria, the mother of his baby daughter, were getting married the week after next at the vineyard, my wedding gift to the two of them. Maybe there were also Hispanic superstitions that involved weddings and skeletons. Dear Lord, I hoped not. Antonio was already jittery enough about this marriage.

I’d been in the barrel room when he’d called me—during harvest we work all hours, seven days a week. Partly because I’d wanted to escape the brutal heat, but also because the lees on last year’s barrels of Cabernet Franc needed stirring. The process is called bâtonnage and we do it to extract more flavor from dead yeast cells and other sediment that slowly sifts to the bottom of a wine barrel. I closed the bung—the stopper—to the barrel I was working on and put the bâton back where it belonged.

Then I texted Quinn.

Going to check on Antonio and the tree. Almost done with bâtonnage. Back soon.

Quinn Santori had been the winemaker at Montgomery Estate Vineyard ever since I returned home from France five years ago, and as of a few months ago, he was my fiancé. Just now he was out in the south vineyard measuring Brix for this year’s harvest of Cab Franc, a test that determined the sweetness of the grapes and whether they were ready to be picked.

Quinn knows me so well. He texted right back. What’s wrong?

Not sure. I climbed into a dark green ATV that was parked outside the barrel room. I nearly hit Send on my reply and then reconsidered.

They found a skull.

Quinn pulled up beside me in a fire engine–red ATV about thirty seconds after I arrived at the cemetery. I had known he would come once I told him what Antonio and Jesús had discovered. He climbed out of his ATV and walked over to mine. Side by side the two vehicles always made me think of Christmas. Or stoplights.

Anvil-shaped clouds the color of dull pewter moved across the Blue Ridge Mountains and streamed toward us like freighters. We were in for another storm later on, a big one. Lolita, sending us one more warning of what was to come. At least the birds were still singing and the wind hadn’t whipped up yet, blowing through the trees until their branches rustled and swayed like dancers.

Quinn slid an arm around my waist and his kiss landed in my hair, which I’d twisted into a knot to keep it off my neck in the soupy heat.

“They really found a skull?” he asked.

“That’s what Antonio said.”

We walked over to where limbs from the huge tree had already been cut into smaller pieces with a chainsaw. The back of the Superman-blue pickup that had belonged to Antonio’s predecessor and had logged nearly two hundred thousand miles was piled high with leafy cut-up branches. Jesús sat on the tailgate smoking, the chainsaw lying on the ground next to him, while Antonio paced back and forth, his phone clamped to his ear. He was talking to Valeria. I could tell by his body language and that low, solicitous tone of voice.

Antonio was lanky, slim, dark-haired, with skin a warm russet brown, and the kind of soulful brown eyes and easy seductive smile that melted women’s hearts. Tears would flow the day he married Valeria. He had walked across the border from Mexico into Texas when he was twelve and never went back—though he did send money to his mother faithfully as clockwork—and taught himself how to do just about anything that had to do with farming equipment and how to repair it.

Jesús was a short, plump spark plug, strong and dependable, born in El Salvador, possessing a swarthy complexion and a silver tooth that glittered when he laughed, which was often. I always knew when he was around, because there’d be laughter among the rest of the men—he was a joke-cracker—and maybe someone would be singing in Spanish, a song remembered from home. Heart of gold, that was Jesús. I couldn’t imagine how we’d get along without either of them, and Benny, our other full-time worker.

Jesús slid off the tailgate. Antonio stopped pacing and disconnected his call, shoving his phone into his back pocket.

“It’s back there,” he said. “In the shed.”

The four of us walked over together, though Jesús hung back a few paces. The girth and height of the tulip poplar had obscured the little stone shed. It had been built by one of my ancestors as a place to keep shovels, rakes, and other garden implements used to care for the cemetery and the graves. I used it to keep flower vases and a collection of little American flags I put on the graves of my ancestors who had fought in our country’s wars on Veterans Day, Memorial Day, and the Fourth of July.

With the roof gone and the interior of the shed now exposed to the outdoors, it was clear why Antonio and Jesús had discovered the skull. When the tree split and toppled over, part of the trunk had landed on the roof and a couple of large tree roots had pulled out of the ground, leaving behind a sizable hole. The skull lay there on its own. My first thought was, where’s the rest of it?

It was human, all right. All of the teeth were intact. Whoever it was, he or she appeared to be grinning at us, perhaps surprised—or pleased—to be discovered in such an unexpected way.

“I wonder if the rest of … it … the body is here, too,” Quinn said, echoing my thoughts. “Maybe we should dig a little more and find out.”

I shook my head. It was already creepy enough to realize I’d been walking over a buried skull all these years every time I used the shed. How had I never sensed its presence?

“We have to call the Sheriff’s Office,” I said. “These are human remains. No more digging.”

“It’s next to a cemetery,” Quinn said. “People are dying to get in.”

Jesús and Antonio grinned.

“You’re not funny,” I said to Quinn.

“Sorry. But, seriously, it’s true. Why wouldn’t you find human remains here?”

“The skull is outside the cemetery. It can’t have moved or shifted under the wall, and certainly not this far away,” I said. “Not inside the shed.”

Antonio shrugged. “Don’t look at me. If you want to call the Sheriff’s Office, Lucie, call ’em. Maybe they can tell you.”

“I wonder how old it is,” Quinn said. “I mean, how long it’s been here.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “What I wonder is why there’s no coffin.”

“There’s an easy enough explanation for that.” Quinn gave me a meaningful look. “It would also explain the skull being outside the cemetery.”

I knew where he was going with this and I didn’t like it one bit.

“What do you mean?” It was the first time Jesús had spoken and he sounded ill at ease. “You think it’s el diablo?”

“Don’t worry, Jesús. Quinn’s not talking about anything supernatural. No ghosts. No devil,” I said.

He nodded, seemingly reassured. “Okay. That’s good.”

I knew what I said next would upset him all over again. “Not exactly. What he means is that whoever this is was murdered.”

Two

Murder. The word settled over the four of us like thick, dark smoke, reducing everyone to uneasy silence. Maybe whoever this was wasn’t laughing after all. Maybe it was a grimace of pain or a final agonized scream.

Quinn cleared his throat. “We could be getting ahead of ourselves here. Maybe … the ground did shift. Maybe the roots of the tulip poplar caused it to heave, and the body ended up out here instead of inside the cemetery. It happens all the time at old graveyards.”

“Thirty feet?” I said, giving him an incredulous look. “Inside the shed?”

“Okay, so that’s a crazy idea. Unless the shed was built after this person was buried.” He shrugged. “But why do it right next to a cemetery? That’s weird, don’t you think?”

I did.

I pulled out my phone. “I think it’s time to call nine-one-one.”

* * *

THERE ISN’T A LOT of crime in Atoka, Virginia, population two hundred and sixty, give or take. The town—village, really—is located in the middle of the affluent heart of Virginia’s horse-and-hunt country next door to better-known Middleburg. Around here everyone knows everyone else, and we know each other’s business, as well. Very little happens—good, bad, a scandal, a celebration—without becoming the number-one topic of conversation the next morning around the coffeepot at the General Store. Six months ago we’d finally installed an alarm system at Highland House, my home, at my brother Eli’s insistence after someone walked in one night that shouldn’t have been there. But before that we’d rarely locked the doors and no one who dropped by to visit ever used the doorbell. Mostly folks opened the front door, stuck their head in, and yelled “Yoo-hoo.”

On a quiet, sultry September afternoon it didn’t take long for a tan-and-gold Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office cruiser to drive up Sycamore Lane, the private road that wound through our land, and park at the bottom of the hill below the cemetery. Right behind it was an EMT van. I was grateful they didn’t arrive with lights flashing and sirens blaring, which would have alarmed the winery staff and any visitors to the tasting room. Right now, though, what worried me more were the jangled nerves of our migrant grape pickers, even the legal ones. Lately the men had gotten so edgy in this new immigrant-unfriendly era that I knew every one of them would be dead certain ICE had arrived.

The discovery of a body at Montgomery Estate Vineyard wouldn’t remain a secret for long, but just now the fewer people who knew about it the better. A man climbed out of the cruiser and a woman got out of the van.

Quinn squinted at them and said, “Don’t we know that deputy? Looks and walks like a bear? What’s his name?”

“Mathis,” I said. “Biggie Mathis. He’s been here before, remember?”

Quinn nodded. “Hope he doesn’t think we make a habit of this,” he said under his breath as we waited for Deputy Mathis to lumber up the hill along with the woman.

Biggie Mathis took off his cap when he reached us and appraised the four of us like we were waiting for the detention hall monitor to show up after school. “Ms. Montgomery,” he said, nodding at me. “Good afternoon. I understand you called nine-one-one about a body. Someone found human remains.”

From his matter-of-fact tone he could have been talking about the weather. At least he didn’t say again.

“That’s right.” I indicated Antonio and Jesús. “This is Antonio Ramirez, the farm manager here, and Jesús Echeverría, another of our full-time employees. The two of them discovered the skull inside an old storage shed when they were removing a tree that came down on the shed and the cemetery wall. You already know Quinn Santori.”

Biggie pulled out a notebook. The EMT, an athletic-looking woman with short steel-gray hair, headed for the shed.

“Ustedes hablan inglés?” Biggie asked Antonio and Jesús.

“We do,” Antonio said and Jesús nodded.

“Tell me what happened,” Biggie said.

They finished their story as the EMT came over to Biggie. “I called the M.E., Big. He can have the honor of filling out the paperwork. I don’t know why I got called out on this one. That skull is DOA. Desiccated on Arrival. Whoever this is has been here for years. Looks like the body was dumped, too. The grave’s not really that deep.” She surveyed the four of us and said in a brisk voice, “Well, bye all. I’m taking off. I’ve got a family barbecue tonight and I need to get home and make coleslaw. Have a nice day.”

As she left, a dusty station wagon the color of mint ice cream with two-toned wood-grained paneling on the sides drove up and parked at the bottom of the hill, taking her place.

Quinn let out a long, low whistle. “Will you look at that?” he said. “A Ford Country Squire, probably 1972 or ’73 or thereabouts. Haven’t seen one of those for ages. Looks like it’s in just about perfect condition, too.”

“Who is that?” I asked Biggie as a man with thinning white hair, a slight stoop, and a bit of a paunch climbed out of the car. He had a neatly trimmed goatee and wore a pair of horn-rimmed glasses.

“That,” he said, “is Dr. Winston Churchill Turnbull. Brand-new county medical examiner. Lives over in Purcellville. Just got back from service in Iraq.” He pronounced it Eye-rack.

“Iraq? Seriously?” I stared at Dr. Turnbull. “He’s got to be in his seventies.”

“Seventy-four. Came out of retirement to volunteer as a surgeon in one of the local hospitals over there. Felt it was something he needed to do. He came home after serving a year and a half and signed up as a Loudoun County medical examiner. Said what he saw over there turned his stomach—especially the little children caught in the crossfire in that hellhole. He told me after he’d already seen the worst man could do to his fellow man, examining dead bodies and figuring out the cause of death back home would be a piece of cake. A relief, even, because when you’re dead the suffering has ended.” Biggie spoke with a mixture of awe and admiration.

“He sounds like an amazing man.”

“You got that right,” he said and waved an arm at Dr. Turnbull. “Hey, Doc. Up here.”

Winston Churchill Turnbull waved back and sprinted up the hill toward us.

“Afternoon, everyone,” he said, before turning to Biggie. He didn’t seem at all winded from his little jog. “What have we got here, Othello?”

Othello? I cast a sideways glance at Biggie, who looked flustered, but said in a calm voice, “Thanks for coming so quickly, Doc. These folks found a human skull. Apparently dug up by accident when a tree root exposed it. Also looks like it’s been here for a while.”

Dr. Turnbull turned his gaze on Quinn, Antonio, Jesús, and me. His eyes fell on my cane, which I use because of a car accident ten years ago. In spite of three surgeries and a lot of physical therapy my left foot is still partially deformed. The doctors said I’d never walk again. I don’t think of my cane as a sign of disability. I think of it as a symbol of victory because they were wrong. I’d bet good money the man standing in front of me had seen a lot of young people with canes or in wheelchairs or worse—limbless—in Iraq.

“I’m Dr. Winston Turnbull,” he said, zeroing in on me. “Everybody calls me Win. And who are all of you?”

We introduced ourselves and after I said my name, he said, “You make mighty fine wine, Ms. Montgomery.”

“Thank you. And it’s Lucie.” I hesitated and then said, “Will you be able to tell us anything about who this is? Male? Female? How long he or she has been here?”

“Let me take a look first. I’m just a country doctor,” he said, which sounded like a whopper of an understatement after what we’d just heard about him. “First, I need to be sure that these are human remains.”

“They are,” Biggie said. “I guarantee it.”

Win nodded like he agreed, though he seemed like a trust-but-verify kind of doctor, so he went on. “Well, then, the next thing to determine is how long they’ve been here. If they’re old—decades, maybe older—then a forensic anthropologist ought to take over and handle the excavation. Or a taphonomist. In other words, if I determine that it’s not a criminal investigation that involves law enforcement, you need expertise beyond mine.”

The explanation went completely over Jesús’ head and even Antonio looked baffled. “Why would you need someone who stuffs dead animals?” Antonio asked.

Win Turnbull smiled. “Sorry, I guess I wasn’t very clear. I’m talking about a taphonomist, not a taxidermist. An individual who studies human remains from the time of death until the time they are discovered—what just happened today, for example. A taphonomist focuses on what impact the environment had on the body—the soil, the interaction of the remains with plants, insects, or other natural causes that could result in decomposition. He or she decodes how the remains came to be where they are, what happened, hopefully in order to identify who this person was, if that’s possible,” he said. “Families wait in hope forever if they never see a loved one who has mysteriously disappeared, if they don’t have a body to bury and grieve for. Sometimes you can finally give closure to a nightmare that has lasted years. Decades. Not a happy ending, but at least an ending.”

“How do you figure out all this stuff?” Antonio asked. “From just a bunch of old bones.”

“Bones talk,” Win said, with a somber smile. “That is, if you know the right questions to ask, what to look for. Come here, I’ll show you.”

Biggie looked like he wanted to object to us tramping over the area surrounding the grave, but Win gave him a long stare and said, “Their footprints are already all over the place anyway. It would be better if they understand this. Trust me.”

Biggie pursed his lips and nodded, but he still didn’t seem happy. He followed the rest of us over to the newly unearthed grave site. Win went down on one knee and the rest of us formed a semicircle around him.

“Well,” he said, after a moment, “this is definitely a human skull.”

“What else can you tell about it?” I asked.

Win knelt on both knees and bent over so he could study the skull more closely. Then he straightened up and twisted around so he could look up at us. “Probably in her late teens, maybe early twenties.”

Someone young, a girl, who should have had her life ahead of her. I caught my breath and Win’s eyes met mine once again. He had just transformed this vacant-eyed skull into a person, giving her a history.

“Of course I can’t tell you the cause of death,” he said. “There’s no corpse to examine—no tissue, no organs.”

“How do you know how old it … I mean, she … was?” Quinn asked.

“Because of the number of bones. An adult human has two hundred and six bones. A child has significantly more.”

“Why?” Jesús asked.

“Because a child’s bones haven’t fused together yet. It’s a process known as ossification, which develops gradually from childhood until adulthood,” Win said. “Look here.”

He pointed to the skull and everyone, including Biggie, leaned in to see what he was indicating. “In a young human skull, there are a series of zigzag lines that separate the various plates that protect and encase our brains. These lines are called sutures and as we get older, the sutures disappear as the plates fuse together. Hence, fewer bones.”

Win began sketching imaginary lines on the skull with an index finger. “Across the top of the head we have the sagittal suture. From the back of the head to the temple is the coronal suture. The squamosal suture more or less follows the shape of the ear where the temporal plate is located. There are others, but you get the idea.”

“Since you can’t see any sutures,” Quinn said, “is that how you knew her age?”

“As I said, it’s just a rough guess. I’d have to examine the skull more closely. Don’t forget the bones have decomposed while they were in the soil. But I do think she had outgrown puberty. I also believe she was probably Caucasian, based on the eye orbits and the nasal cavity.”

“You can tell it’s female?” I asked. “Just like that?”

“The clearest indication would be to see the pelvic bones,” he said. “Obviously. Which may or may not still be here.”

My eyes strayed to a patch of earth below the skull where more bones might still lay under the soil. It was still within the perimeter of the shed. Was the rest of the skeleton intact? Had the shed served as protection for a body?

“However,” Win went on, “it’s still possible to make some determination of sex from the skull. Males, for example, have larger, squarer, and more pronounced jaws than females. They also have a more prominent supraorbital ridge—in other words, the brow.” He traced a finger where the forehead would have been and then sketched in the eyes over two black, sightless holes. “Males also have more rectangular eye sockets. In general, their bones are more robust than the delicate bones of a female.”

“You’re pretty sure about this?” It was the first time Biggie had spoken in a while. “It’s a young female? I mean, she.”

“I’d want to do a more in-depth examination to confirm it, but yes, I’m reasonably certain.”

There was more silence while we absorbed that information. Young. A woman, just barely. Buried outside the walls of my family’s cemetery in an old shed. Deliberately? To hide her? My stomach churned. For some reason it seemed more disturbing, more … shocking … to know the remains were female, not male.

“Can you tell how long she’s been here?” I asked.

“I’m afraid not,” he said. “Determining time of death—especially when you’re talking about years, or in this case, I would venture to say decades—is a lot more complicated.”

“What about DNA?” I asked. “Is there any way to collect it from bones that are this old, when there’s no hair or skin left?”

I tried to keep my tone nonchalant, asking as a matter of curiosity. Quinn cast a quizzical glance in my direction but I pretended not to see it.

Win began to get to his feet. Quinn put out a hand and pulled him up. “Thanks.” Win brushed the dirt off the knees of his khakis. “You can obtain DNA from teeth, Lucie. This young woman has a very good set of them left. You’d be surprised what we learn.”

“So you might even be able to identify her?”

“If you’re wondering if she’s related to you, my dear, we can swab your DNA and see if we get a match,” he said in a kind voice. “If she’s not, then it depends whether any of her relatives are in our DNA database. Sometimes we get lucky. Other times not.”

Quinn shot me another puzzled look and said to Win, “So what happens now?”

“Right now,” Biggie said, interrupting the conversation, “we’ve got a storm coming and I need to put yellow tape around what’s left of this shed. Until we know more, this is a crime scene. That means everyone needs to keep away. No trespassing. Let Doc Turnbull do his work until we get some more answers about who we’ve got here.”

A clap of thunder boomed directly above us, as if Biggie had planned it to go with his voice-of-God “keep out” edict. I looked up at the sky. Angry black-and-gray clouds swirled like a boiling cauldron clear to the Blue Ridge. The mountains themselves were partially swallowed up by the menacing darkness. The wind picked up and everyone began to move.

“Let’s get this grave covered up so nothing washes away before the storm hits,” Win said, his voice rising to be heard above the wind.

The first fat drops of rain started to fall. “Come on,” Biggie shouted as a devil’s pitchfork of lightning lit up the sky over the Blue Ridge. “We’ve got to get her covered up and get out of here.”

Her.

I wondered who she was.

* * *

UNFORTUNATELY NEITHER QUINN NOR I had put the roofs back on the ATVs so we were both soaking wet and chilled by the time we pulled in to the old dairy barn where we kept the equipment. We drove back to the house in my Jeep looking like something someone forgot to shoot, showered together, and changed into dry clothes. The storm passed almost as swiftly as it had come, leaving behind a cloudless sky, clean, fresh, cool, air, and a Technicolor late-summer sunset that turned golden yellow, then vivid orange, and finally a fierce red over the Blue Ridge. Tonight Hurricane Lolita seemed impossibly far away.

We ate dinner outside on the veranda so we could watch the sun go down. In a few weeks it would be too cool to do this, but for now I reveled in these Indian summer evenings before autumn and chillier nights arrived for good. Persia Fleming, our housekeeper, had left us dinner—Southern fried chicken, homemade potato salad, and green beans picked earlier today from the garden tossed with crunchy slivered almonds sautéed with butter. Apple pie à la mode for dessert. Also homemade.

“I never get tired of this view,” I said as the mountains slowly changed to the color of an old bruise and the sky faded to a deep violet. A few stars winked like tiny lights that had just been turned on. When I was little my mother used to tell me that the Eskimos believed the stars were really openings to heaven that allowed the love of those we’d lost to pour through, shining down to let us know they were happy. After she died, I often looked up and wondered which star—which opening in heaven—she had chosen to send her love back to me.

“Me, neither.” Quinn settled back in his chair, resting his wineglass on his chest. “Want to do some stargazing tonight? We could dry off the Adirondack chairs and finish the bottle of wine at the summerhouse. It’s so clear we’ll be able to see the Milky Way since the moon doesn’t rise until after midnight. Plus it’s probably one of the last opportunities for seeing the summer triangle.”

Of all the unexpected things I discovered about my fiancé, the biggest surprise was his passion for astronomy, along with a far-reaching and eclectic knowledge of outer space, stars, planets, meteors, comets—actually, any phenomenon that occurred in the night sky. He was especially fascinated by the Messier Objects, a collection of 110 astronomical objects consisting of star clusters, nebula, and galaxies. The original list, compiled in 1771 by a French astronomer named Charles Messier, had consisted of forty-five items. Over the years, however, astronomers continued adding to it until what had become the most famous list in astronomy totaled 110 items. Every year on a designated night between mid-March and mid-April—when the entire collection of Messier Objects was visible in the night sky—Quinn took part in the “Messier Marathon,” a competition organized among amateur astronomers to locate as many items on the list as possible that one night.

The first year Quinn moved to Virginia from California my father had let him set up his telescope at our summerhouse, which was on the other side of my mother’s rose

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...