- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

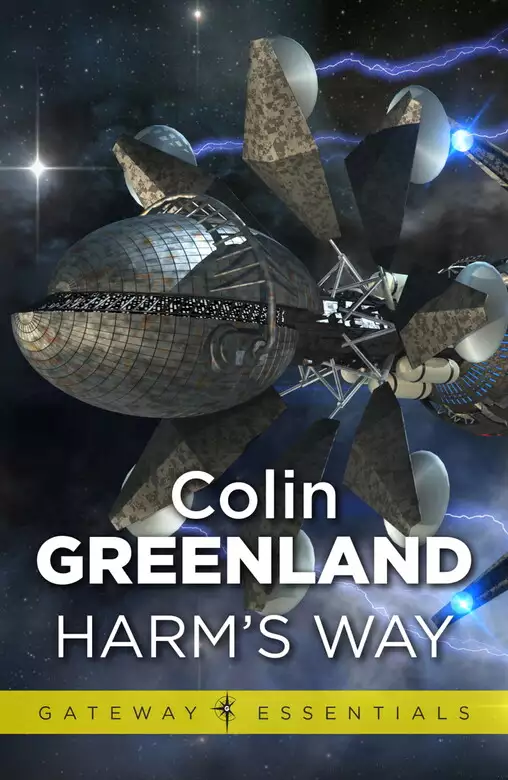

Synopsis

'YOU KEEP OUT OF HARM'S WAY, SOPHIE FARTHING' Her father's advice seemed only sensible. The flying island of High Haven was a dangerous place. So what was she doing down on the docks at midnight, talking to the sinister gentleman with the iron jaw? Where had he come from on his majestic space yacht? And why did he laugh when she spoke of her poor dead mama? Sophie only wanted to talk to him again. She didn't really mean to stow away - certainly not on the wrong ship. Her unintended quest is to take Sophie far from home, to the pleasure gardens of the Moon, the grogshops and grime of Lambeth Walk, through the perilous Asteroid Sea and the cruel canyons of Mars where Angels fill the red sky with their ravenous cries.

Release date: June 24, 2013

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 356

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Harm's Way

Colin Greenland

By Divine Order, it rains, and like the Mercy of Heaven, dropping on the Cathedral of St Paul; the great grey dome of Sir Christopher’s monument shines with rain. Below in the City, like the bounty of all the worlds, it rains, on the pinnacle of the Exchange where Urania stands, arms wide to gather it in. Water runs from her marble elbows. Down the spires of many a lesser church it courses, and cascades down the lofty windows of Garlick Hill where the telescopes stand idle. There will be nothing to view today: no stars; no ships, though the entire Fleet under full sail should pass by overhead; nothing but the rain, which abides no man his entertainments, and goes tumbling heartlessly on, down towards the little and low streets, that are all barnacled with cock-eyed roofs and squinting casements. Even-handedly it pours on both the cab that comes jolting into view and the beggars tagging along behind, a mixed gaggle of urchins elbowing with a tattered brood of Cæruleans, blue as forget-me-nots.

The cab stops by the corner. The alien beggars jump up on the mudguards and paw the door, squealing and whining for alms.

‘Get out of it!’ The cabman curses the whole pack in a growl. The urchins take this as a signal to jostle harder, with jeers and cuffs. ‘Holloa the Blue Boys!’ they shout, and whistle, stretching with their filthy fingers the corners of their mouths.

Nothing happens. The door of the cab does not open. The cabman shoulders his whip and ignores them. He ignores everything. He sits hunched in his greatcoat, oblivious, impervious to the rain.

The rain pelts the cabman’s hat. It pools in the upturned brim and streams down behind his back onto the roof of his cab; spills over onto the hindquarters of his long-suffering horse; trickles thence, as by a process of natural justice, down the necks of the struggling beggars; and sinks, like all things at last, into the mud.

Hunched under a single umbrella and holding an empty shopping basket between them, two women come splashing hastily around the corner. Though it is a filthy day when none but dogs and desperate men would be out of doors, yet there are mouths to feed. The women take no notice of the cab as they go by, though one of them turns and shouts something angry and admonitory at one of the urchins.

No sooner have the women run past and disappeared into the rain than the cab door opens finally and a man leans out. He seems to be an ordinary human man, in a pea-coat and muffler and so forth, though he has come out without his hat and wears his coat collar turned up against the vileness of the day. He takes out a couple of ha’pence and throws them back up the street, scattering the beggars, who run after them. Descending, he does not look up at his stoical charioteer but knocks with his knuckles on the side of the vehicle; and we see that neither has he any gloves. The cabman clicks his tongue and the cab jolts away along the street.

Reconvening around the erstwhile passenger in hope – for those who have nothing must always have hope – the beggars look up. Between the wings of the collar they see the white wedge of a man’s face, a man of perhaps five-and-thirty years, clean-shaven. He is a short man with a broad head and brown curly hair. With his cab and his practised handful of coppers, and a gold signet ring which the sharp eyes of the little blue men were quick to spot on his finger, he might almost be a gentleman; but his trousers are plain dun worsted and his boots are ungaitered and dull. For certain he is no one who belongs to these poor streets; nor does he look like one who might have business here – not a tradesman; not a bailiff’s man; nor a policeman either. He looks very much like no one in particular. He may be some kind of sailor, in that coat. He has the sailor’s air of being equal to all places, beneath this grim sky or any other. The way he thrusts his hands into his coat pockets and walks briskly off between the beggars, with his head up and heedless of mud and puddles, declares him for a man of purpose; and one who will never in his life lose his way, even here in the lowest and most entwining entrails of the mother of cities.

A deep bell tolls the hour as he rounds the corner and enters the dismal back-street from which the women came. A sign on the wall above his head reads: Turkey Passage. The visitor passes it without inspection. The rain continues.

The beggars have already dispersed, vanishing back into their murky dens. Perhaps the speed of their departure was not unconnected with the two tall, powerful silhouettes that have come hurrying through the rain, across the street and around the corner after the unparticular man. Two huge, high-shouldered figures they seem to be, in greatcoats and with what look like enormous Scotch bonnets on their heads. They move through the clinging mud with an easy lope that speaks of origins on a world of fiercer gravity than this. Whether the man knows he has acquired these menacing adherents, there is no way to tell. His back is most uncommunicative.

The two shadows sidle into deeper shadows in low adjoining doorways. Though the thoroughfare is so narrow, they are lost to view. Perhaps a keen ear might hear them breathing, harsh and deep as aged bulldogs. Or perhaps that is the hissing of the rain.

The unparticular man walks directly down Turkey Passage to a particular door, quite as though he had been there before. He knocks, and waits. While he stands there a rat runs over his boot. He kicks at it, and is rewarded by a shrill squeal. He does not smile. Nor does he look over his shoulder at the deep shadows of the doorways behind him. He waits, and thinks of nothing at all.

A young girl, thin and pale with some twelve starveling city summers, cracks the door to look at him. She looks at him doubtfully. She does not know him, and it is early yet for customers.

‘Molly,’ the man says in a low tone; and the doorkeeper stands back without a word to let him in.

As he crosses the threshold, the unparticular man gives the girl a single, searching look. A future apprentice in the trade, no doubt. Too old to concern him, her thin young face already grave with ancient cares. He dismisses her from his attention.

The hallway of the house is narrow and black as a coalmine. In the open door of the front room a man stands leaning against the wall. He does not greet the visitor, though he inspects him. He is a large hulk of a man like a hulk of timber. His sleeves are rolled up, and the arms crossed across his bulwark of a chest are blue with old tattoos. The grip of a bludgeon protrudes an inch from his belt.

The visitor is not offended. He likes things to be clear. He ignores the bully as he ignores the girl.

The hallway reeks of damp, and boiled vegetables. There is the thin, piteous sound of a baby crying in a room somewhere at the back of the premises.

‘Take your coat sir?’ says the girl.

The visitor does not respond. Perhaps he is a foreign gentleman, and understands no English.

The girl is supposed to take their hats, if they have ‘em, and their coats, if they will, as a surety; but if they won’t, there’s an end of it. Moreover, she is supposed to quiz any customer she doesn’t know to make sure he has money; but there is something about this one’s very impassivity that checks her. She glances at the bully, but he does not move or speak.

‘Upstairs at the front,’ the girl says. She leaves the hall while the caller starts to mount the stairs. He is a man, and of no more account than other men. The girl returns to her other chores; to the kitchen, and the crying child.

The door to Molly’s room is ajar. She opens it to his knock. There she stands in the doorway, a grubby dressing gown of some worn shiny stuff in powder blue and pink pulled around her ample frame. She smiles at him as if she has known him for years. It is a smile of the lips and teeth that does not much concern the eyes. A bitter smell escapes from the room behind her, composite of powder and sea-coal and gin, and the reek of tired, coarse flesh.

Molly’s visitor spends a moment considering her, dispassionately, as if through the eyes of another man. Her figure is plump, bosomy: the motherly kind, who tends to men’s woes. Her head of bright orange curls she owes to a bottle. Even at this hour her face is powdered and painted, her mouth a broad, succulent bow of carmine lipstick. Above it, her black-lined eyes are tired, creased at the corners by her life, though there is life in them yet. She looks like forty pretending to be twenty, is perhaps halfway in between, as far as the calendar is concerned. She does not look diseased.

The unparticular man makes an unconscious gesture, running the tip of his finger down his cheek.

‘Come in, sir, don’t stand out there in the cold.’

Her voice. Her voice is melodious. That would have had a lot to do with it.

He reaches once again in his pocket and puts money on the table by the bed. He handles it vaguely, casually, as if it has no value to him, as if he has too much of it to give it any attention.

Molly Clare too is now wondering if perhaps he is a foreign gentleman. ‘Lord bless you, sir,’ she says. By the gratitude in her voice it is apparent to him he has given her plenty, not that it matters.

He glances around her boudoir. It is not as grim as its setting. There are even lace curtains at the narrow window, and a fussy green plant in a pot. A coal fire burns in a small grate. Between that and the bed stands a wicker chair, its arms and seat bowed from the weight of Molly’s body. On the mantelpiece are a few knick-knacks or ornaments – gifts, conceivably, from gratified patrons, for there are pieces that seem to be bronze and jade rather than the gimcrack and painted plaster one might expect in the room of such a woman. In fact, for all the foulness of its purpose, the whole room has a cosiness to it that seems to set at naught the world of mud and rats and cold November rain.

Her bed is of iron, and her wash-basin enamel. Her visitor sees that beneath the bed her chamber-pot has a cloth over it. Meanwhile Molly has cast off her dressing gown and poured water, and has started washing under her arms and under her shift. She talks to him all the while, in cheerful, complimentary, automatic tones, like a barber. ‘I know you gentlemen like a girl fresh,’ she is saying. She has noticed his ring, plain gold with no insignia, and the buttons on his waistcoat, mica from one of the moons of Mars.

He is not listening to what she is saying, and neither is she. He undresses, putting his clothes on the chair. He has decided to have her, a small, secret gesture of defiance, because he was not told not to, and because the implied insult amuses him.

Molly is puzzled. Once, not long ago, it was different; but these days, in this room, there are none but common men, and two kinds only of them: those who are lustful and urgent, and those who are guilty and contemptuous. This one is neither. He remains distant as the stars. As much as he’s paying, he says nothing of any special needs or fancies. His prick is hard, but his face is smooth, closed.

He seems like an inspector of women. Molly has heard of men who do that, who travel from port to port, sampling women of every race and kind, like collecting butterflies. Or it may be there is something on his mind. After they spend, some men like to confess to her, to pillow their heads on her soft breasts and tell her all their troubles. Not this one. He is as secret as the grave. She feels obscurely pleased, and kisses his chestnut curls.

He lies with his head on her shoulder, not objecting to the sweat of her stubbled armpit. ‘You are a good girl, Molly,’ he tells her, as familiar as you please, and she wonders if perhaps he has been before; but it does not do to let them know you don’t remember them, so she lets it go, listening to the sound of the rain on the window, and wondering when the other girls will be back from the shops, and what they will bring for supper.

Her visitor sits up and swings his legs out of bed. He sits with his back to Molly, looking at her bits and pieces on the mantel. He picks one up. It is a photograph in a frame of dark green metal. It shows a woman with corkscrew ringlets, wearing a low-waisted dress, high-sided boots and a Toriodero cap and bolero. She stands against the corner of an Italianate loggia, with a shiny plain and a black sky beyond. There are other people in the background, but they are only incidental, he judges, because it was taken in a populous place. They seem to be ladies and gentlemen of quality, such a crowd as one might see on any night, leaving the opera or ballet. Their figures are blurred with movement, and none of them is looking at the camera.

The woman is Molly Clare. She is holding a bouquet of white flowers with long, slack petals and smiling a bold smile. The picture is quite recent, no more than two or three years old. It has been curiously cropped, perhaps to fit into the frame: part of her left shoulder is missing.

‘What’s this picture, Molly?’

She lifts her head to look. ‘That? That’s a holiday souvenir. That’s me at the Sea of Tranquillity.’ She speaks proudly, rolling the long word off her tongue, enjoying the feel of saying it; though there is sadness too in her tone. ‘D’you know it?’ she says.

He does not speak, and it is hard to tell from his uncommunicative back whether he does or no. He merely returns the picture to the mantelpiece, as if it has no interest for him. Molly is not offended. She is at ease now, he has paid for the rest of the day and all night too, if he fancies, for all he was so quick. He is reaching into his clothes on the bedside chair, she supposes for a cigar case. She thinks about a pot of tea.

When he turns back to her, he is holding something out towards her, something slim and black. She thinks it is a cigar and he is offering it to her, fancy that! And she starts to laugh, but stops at once because with his other hand he has taken hold of her hair, pulling her head sharply back. Out of the corner of her eye Molly sees the thing in his hand flash out a light too bright to look at. She hears a low sharp buzz and smells the tang of ozone. She gasps, her red lips framing words that will not come. She sees the damp place on the ceiling whose shape always reminds her of the head of a donkey braying. And then she sees no more.

The blade of his knife is made of light, cold buzzing light. It has poked a tiny slit in her neck, and cauterized the flesh on its way in, so there is very little blood. While Molly Clare’s plump hand came up to the place and her tired eyes bulged with shock, trying to focus for the last time, the unparticular man saw a vigour, an anger in her gaze, as of a fighter taken off guard. As though she understood, but was not expecting it, not this morning, not suspecting him. Now, as those eyes fade and fall still, they seem to have filled with a strange exultation, almost with relief. The man is skilled at reading faces, the expressions that come and go in them; yet this expression he cannot interpret. He dismisses it, and lets go of her.

When he squeezes the hilt of the knife, the blade vanishes. He slips the device back into the pocket of his jacket where it hangs on the back of the chair, then retrieves his shirt and underthings, and puts them on. He feels chilly after his exertions. He takes the poker from the stand in the hearth and stirs up the tiny fire. There is a smell of warm wet wool in the room. Pulling on his trousers and settling the braces on his shoulders, the man steps over to the window and opens it. The frame is warped, and squeaks as he pushes it up. Rain splashes on the window-sill and spatters into the cosy room.

The unparticular man does not lean out of the window, but bends down to the gap and puts a whistle to his lips. He blows. No sound comes from the little instrument that human ears can hear; but a shadow stirs in the black mouth of a doorway on the other side of Turkey Passage.

Molly’s visitor puts the whistle back in his pocket and closes the window. He makes a cursory search of the cupboards and drawers in her room, such as they are. He finds nothing but feminine fripperies, underclothes, sexual accoutrements and articles of hygiene; no letters or papers. He seems to be looking for some particular thing, but without finding it. He looks beside the wash-basin. Nothing. Now he takes Molly Clare’s hands, one, then the other. He looks at her fingers, which are bare. She was a discreet woman. She would not have lasted so long had it been otherwise. Now she lies on the bed, staring fixedly at the ceiling. Since her soul has flown, an indefinable sadness has come into the room. The curly-headed man with the unparticular face sits beside her pulling on his stockings. He hears an indistinct thumping sound from downstairs.

While he fastens his muddied boots he looks again at the picture standing on the mantelpiece. He recognizes no one in it. He destroys it anyway, crumpling it as he pulls it out of the frame and throwing it on the fire.

The stairs creak under a weighty tread. The door of Molly’s room opens, and in comes one of the tall figures who followed her visitor up the street. His appearance is quite alarming. He is taller than the door, almost too tall for the room, and his head inside the over-sized Scotch bonnet is shaped like the head of a hammer, with a large globular eye at each of the ends. His head continues down without the benefit of a neck into his chest, where his shirt has been cut away to accommodate two goitrous organs that continuously swell and flatten like bladders beside his mouth, which is oblong. His skin is a chalky greyish-blue colour, perhaps from poisoning by this alien air. With his greatcoat open, the smell of him is something between strong cheese and rotting leaves, overcoming the taint of burnt flesh that hangs in the room.

The hands of the intruder are like the paws of a mole, but their hard shiny skin is more like the carapace of a lobster. There is blood on these hands, red human blood. The newcomer gapes at the man sitting on the bed: a bovine, lugubrious expression. The man nods. His accomplice breathes hoarsely, but does not speak. He bends over the bed to attend to Molly with a knife of his own, a perfectly commonplace mild steel skewering knife, such as is used every day by every butcher in the land. There is a vile unnecessary thing to be done with the entrails, for the sake of Scotland Yard.

Through the open door Molly’s visitor can hear that the baby is no longer crying. Indeed, there is no sound at all from the rest of the house. The man goes downstairs while the brute is about his work, leaving the money on the table beside the bed. He finds another brute at the bottom of the stairs, with another knife. The tattooed bully of the house lies beside him on his back on the floor, his eyes stark and staring with fear he no longer feels, wherever he is. His little club never left his belt. The curly-headed man cocks an eyebrow; ponderously the brute nods. They are Hrad, from the planet Jupiter, or a moon of it. Pushing past, the visitor looks swiftly into the kitchen, and the rest of the rooms downstairs. His assistants have been thorough, in obedience to their instructions. None who lived here does so any longer.

The curly-headed man runs a finger down his face, his unparticular face, and steps out of the back door, pulling up the collar of his pea-coat. A puddle reflects him an instant while he pauses, getting his bearings; then he is gone. In a minute more the Hrad have finished their work and leave too, crossing a malodorous yard and loping away along the maze of alleys.

It continues to rain, the foul, chill, smoky rain of old Earth.

From the steps of the Aeyrie the visitor can see the ships that come and go from the Port. Today, among the nine o’clock departures we might have marked the frigate Leventelá with her Boston rig, and the fearsomely blackened Criollo of Aparicio Sarmiento, Admiral of the Argentine. One by one they climb, nosing into the hazy sky, while around and about flock the giant blue dragonflies of the region. With their metallic lustre and glinting, faceted eyes these resemble masterpieces of ornamental crystalry, creations of Fabergé animated by clockwork. From this height you would not guess they are the size of eagles. Now they hover high over our heads; now, at the boom and clatter of the opening of the Aeyrie’s great doors, they flicker and dart, vanishing away into the diamanté groves far below. Their wings blur like oval slivers of pale light.

The Aeyrie is a very private institution, and not easy of access. These portals of darkly gleaming local mahogany are removed from all but the men best qualified to reach them: those who come out of the sky; by means of the abstruse conductivity of space itself. For the Aeyrie is the Headquarters of the Most Worshipful Guild and Exalted Hierarchy of Pilots of the Aether. It is their college, their club, their Livery Hall. Here each man comes, first as a cadet reporting for training; then as a freeman, to check the postings and catch up on the news; and finally as a master of the craft, to relax between jaunts and quaff a bumper or two, to loosen his belt and collar and let the cares of his calling slide from his shoulders. In the saloon and in the private dining rooms he may entertain his fellows and associates; a good deal of business is done around the bar and on the verandah. The fair sex is not admitted, to the guild or to its sanctum: neither women nor conversations about women, though that old rule is dishonoured daily.

Thus every pilot in the system has occasion to put in an appearance at the Aeyrie. Some of them practically live here. In the cool and spacious foyer, out of the sun, are generously proportioned ottomans where a member has only to sit and wait, and anyone he wants to see will eventually come strolling across the yellow carpet. That is where we find Captain Arthur Thrace of the Unco Stratagem, sitting and looking about him.

Today there is a larger group than usual of idlers, reading the papers and gossiping around the notice-boards. Last night Habbakuk of the Low North-West received the Master’s Silver Medal, and there was much jollity in the commons. Mr Habbakuk failed at the sconce and the Master’s portrait was drenched with a soda siphon; even now the slaves are still cleaning up. The Master himself, Lord Lychworthy, twenty-eighth Earl of Io, was not present for the ceremony, which was performed by his emissary, Mr Cox. His Lordship is rarely here, but Captain Thrace can see a good sample of the exalted and worshipful: Commodore Delauney having a word with the porter, no doubt asking him to keep an eye on his son; the Sarkar of New Borneo nodding respectfully as he passes the old hands, grim-faced and gaunt, who occupy the best seats in the bar. It is obvious just from looking at them that these scarred old men know every inch of the flux; their very bones are hollow from the blowing of the solar wind.

Around them slump pale specimens in neckscarves, habitual inhabitants of the fug of the inner commons. Inert and uncommunicative, they lounge all day in low armchairs drinking scotch and soda, wearing their purple glasses but never seeing the sun. See where the Ophiq steward appears, duplicate book in his large fist, to confer with one of them in the matter of an outstanding account. And there, in the hallway by the stairs, did you catch that glimpse of a white satin cloak? It is a starman, on his way up to pray. The east wing of the Aeyrie contains a whole floor of meditation rooms, each with its single white chrysanthemum or small bowl of beaten brass. Starmen are ascetics to a man, devotees of the inner arcana of the mystery. They are the pure-hearted knights of space, and disapprove of the lack of spiritual refinement in their lowlier brethren. It is his devotion to the physical world, the starmen believe, that keeps the subsolar pilot paddling in the shallows of space.

Yet that slender white-caped figure sailing lightly upstairs has more than he imagines in common with the japesters and sluggards here below. Both world-hoppers and starmen are Romantics. All pilots are Romantics. These men with their Canopan cigars or their zen contemplations, they will be all gone in three days’ time. Look for them then beyond Ceres, out on the open way. Then you will see them in very truth, in full array upon the bridge of some six-master, then when they place the circlet of gold about their brows and open their mind’s eye to the current of the flood – that is their purpose and their joy. To stand on deck, your foot braced on a spar, and look out in the hard glare of space at the sails, yards of sheer white-black nothing, gossamer-thin, spread out across leagues of nothing blacker yet – to see them spread and swell in the aether wind – to raise your hand and point the way of fresh tides and high streams where the ship can run – what greater glory has life to offer? There they go, the stars in their eyes, and in their ears the pure high song of the void. God speed them! Without them the worlds would scarcely turn – shops and larders could not be filled – the explorers of the great empires of Earth could not go forth to shake hands with their brothers under other suns.

Mr Cox, Lord Lychworthy’s emissary, is already aboard his master’s yacht the Unco Stratagem, ready and waiting to leave. The pilot for the Earthbound run is late, as usual. That is why the captain has been obliged to come down in person to fetch him. And of course, he is nowhere to be found. He is not in the commons; nor in the garden; nor yet on the roof, where his kind like to gather. That is why Captain Thrace has fetched up here, on the ottoman nearest the door; on the very edge of the ottoman. One or two men nod civilly as they pass, seeing the crest on his uniform, but nobody else sits on his ottoman, though there is plenty of room. Captain Thrace is not a member of the Pilots’ Guild.

Spotting a gentleman in need of service, the steward toddles up and stands directly in front of the captain. Their eyes are on a level. ‘Sir?’ says the steward in his fluting voice.

‘Oh. Ah,’ says Captain Thrace. He clears his throat. ‘I – ah, ahem – don’t suppose you’ve seen Mr Crii today, have you, steward?’

‘What you suppose is true, sir,’ toots the steward. The captain flinches from the earnestness of his tone. He looks away, then back at him, doubtfully.

‘Beauregard Crii,’ says the captain. ‘You do know him?’

‘I do, sir.’ The steward remembers Mr Crii perfectly, and his father. He remembers Mr Habbakuk’s father, and Lord Lychworthy’s father, and all their fathers, for the talent runs that way, and the Ophiq are a race of marked longevity.

The steward is greatly vexed by the outrage done to the Master’s portrait. He is afraid that this man, whom he knows by sight, will mention the incident to Mr Cox, who will be obliged to report it to the Master himself. Clapping his huge hands he summons a page, and sends him about the halls to call for Mr Crii.

Meanwhile Captain Thrace looks around the foyer, over the bald brown dome of the steward’s head. He takes out a perpetuatum-stained handkerchief and blows his nose. The acidity of the air is annoying him. ‘I imagine he’s not in yet,’ he says gruffly.

‘To imagine is free,’ says the steward.

‘What?’ exclaims the captain.

‘Truth is not to be denied, sir.’

‘Ah. Hm. H’mm-hm.’ The captain folds his hands and glumly considers the unreliability of angels. Mr Crii, confound him, will turn up when it pleases him and not apologize for being late. It would no more occur to an angel to apologize for anything than it would to a cat.

The Ophiq, having no waist, cannot bow, but he gives his customary bob, and toots, ‘May I enquire after his lordship’s health, sir?’ He asked the same question of Mr Cox, of course, but he is helpless to convey his concern without alerting the captain to the state of the painting.

‘What?’ replies Thrace again, bewildered. ‘My health? Perfectly fine, h’rrumph, thank ye kindly.’

The Ophiq goes light blue. ‘His lordship’s health,’ he says.

Captain Thrace realizes he means Lord Lychworthy. ‘How the devil would I know?’ he says, irritably.

The steward is afraid of Lord Lychworthy. He is one of the most powerful men in the universe, and one of the most private. His father had a temper, as did his grandfather, but this one’s displeasure is dangerous to incur. He disposes of inadequate staff as other men dispose of gnats. His relatives have a nasty knack of disappearing on odd jaunts to obscure corners of the solar system. With his snout the steward twitches the corner of a dishevelled Telegraph into line.

Though he has no doubt of the time, Captain Thrace looks up once more at the array of clocks on the wall.

‘Nine and thirty-nine, sir,’ says the steward; and now he tidies abandoned cups onto a tray.

‘Thank you,’ says Captain Thrace stiffly. He continues craning his neck hopelessly around.

Hopefully, the steward pats the captain’s boot with his big mitt. The captain jumps. ‘A pot of tea, sir?’ suggests the steward.

‘No. H’rrumph. No, thank you, steward.’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...