- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

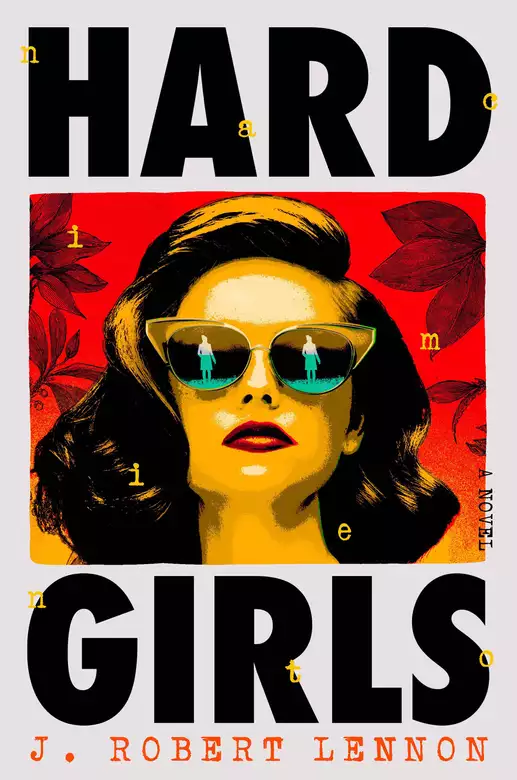

Synopsis

Two estranged twin sisters hunt down their elusive mother, facing the darkness they tried to escape, in this razor-sharp crime novel from "master of the dark arts" J. Robert Lennon. (Kelly Link)

Jane Pool likes her safe, suburban existence just fine. She has a house, a family, (an infuriating mother-in-law,) and a quiet-if-unfulfilling administrative job at the local college. Everything is wonderfully, numbingly normal. Yet Jane remains haunted by her past: her mercurial, absent mother, her parents’ secrets, and the act of violence that transformed her life. When her estranged twin, Lila, makes contact, claiming to know where their mother is and why she left all those years ago, Jane agrees to join her, desperate for answers and the chance to reconnect with the only person who really knew her true self. Yet as the hunt becomes treacherous, and pulls the two women to the earth’s distant corners, they find themselves up against their mother’s subterfuge and the darkness that always stalked their family. Now Jane stands to lose the life she’s made for the one that has been impossible to escape.

Set in both the Pool family’s past and their present, and melding elements of a chase novel, an espionage thriller, and domestic suspense, Hard Girls is an utterly distinctive pastiche—propulsive, mysterious, cracked, intelligent, and unexpected at every turn.

Release date: February 20, 2024

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Hard Girls

J. Robert Lennon

It wouldn’t have looked unusual to anyone peering over her shoulder. It would have looked like spam. That’s where she’d found it, the spam folder. But it wasn’t spam. It was from her. Jane knew this despite the anonymous, clearly temporary email address ([email protected]) and the innocuous subject line, Prescription drugs via UK rail, lowest prices, no wait for approval! She wouldn’t have opened it if not for UK rail. That’s what meant it was from her.

The contents of the email consisted of one line of text and one image. The text read, “No appointment needed, no waiting, call today!” The image had been hidden from her by the email client, leaving only a small broken-image icon beneath the text.

She moved the cursor over to the icon. The words LOAD IMAGE appeared beside it. Her finger hovered over the mouse button; if she clicked, she could see what had been hidden.

Instead, she took her hand off the mouse and hit the delete key. The email disappeared.

Jane involuntarily gasped. Sweat had broken out on her face and under her arms. She stood up, and her chair rolled backward and crashed into the bank of filing cabinets. Across the room, Lydia and Carmen looked up from their computers.

“Are you going to the commissary?” Carmen wanted to know. “Can you get me a scone?”

“I wasn’t—No, actually, yes. Yes, I can get you a scone.”

“Currant, please, cranberry as a last resort. Not the one with the figs.”

“Got it.”

“All I have is a twenty, can I pay you after lunch?”

“Anytime.”

Jane drew a deep breath, smoothed her sweater, and slipped her bag over her shoulder. She walked to the door, opened it, and entered the hallway.

Students hurried past her on either side, about to be late for class. Their shoes squeaked on the linoleum, wet with tracked-in rain. This building, Seddon Hall, was 150 years old; it was drafty in the winter and roasting hot in the summer, and on rainy days it felt as clammy as a big canvas tent. History occupied the second floor, with philosophy upstairs and the dean underneath. And below that, in the basement, the commissary.

She took the stairs. Students sat on them, gazing at their phones. Jane was thirty-five, hardly old enough to start bemoaning the habits of youth, but she could not understand the students’ obliviousness to the space they took up. They sat on the floor outside professors’ offices with their legs extending across the hall and looked shocked when you asked them to move. They blocked doorways with their enormous backpacks and spread their possessions over as many chairs and tables as physically possible. And then there were these two, the stair sitters. It was like they wanted to be kicked.

“Excuse me,” she said to the two girls in her way. She couldn’t go around them, as the custodian was mopping the stairs; he clearly was annoyed with them as well but perhaps had hoped they’d move of their own accord.

They didn’t look up. “Kids,” Jane said, more loudly now. “You’re blocking the stairs.”

One of them craned her neck to look up. She blew a lock of hair out of her eyes and said, “You can go around.”

“Get the fuck up,” Jane said. “Now.”

She hadn’t heard this tone of voice come out of her own mouth for years, not since Chance insisted that they enter therapy to talk about her anger and its effect on their marriage. It was the voice that had frightened their daughter, the one Jane deployed when her bare foot was jabbed by a wayward toy, or when she was pestered too long for a snack. For much of her adult life this voice had been a vital tool in her defensive arsenal, a warning and a threat.

But here, as at home, it was too much. The girls were up and scurrying away in an instant, the “go around” girl muttering “Jesus” under her breath. Even the custodian seemed shocked. She apologized as she passed, head hung. She’d left the office to calm down! Instead, every muscle in her body had tensed up and her pulse throbbed at her temples.

The crush of students in the commissary made it worse; she felt exposed, cornered. She tended to avoid the building’s public spaces when classes were letting out; only when the campus drew in its breath every hour did she feel comfortable away from her desk. In line, she mastered herself, closing her eyes, slowing her heartbeat. She bought Carmen’s scone and a coffee for herself, and, as an afterthought, an oatmeal raisin cookie. “Separate bag, please.”

At the second-floor landing, she walked not south toward the history office but north, to 263, the final door in the cul-de-sac that also contained 261, the supply closet, and 259, the IT storage room. Like all the doors on this floor, 263 was of stained hardwood, and dominated by a large frosted-glass window through which you could discern the hunched silhouettes of professors puttering among their books.

You couldn’t discern any professors in 263, though. The window was covered from the inside with an old, yellowed map of the Soviet Union. The map was the last thing she saw every time she visited 263. She frequently visited 263 because it contained her father, Professor Harry Pool.

She awkwardly transferred the snack bags to her coffee hand so that she could knock. A frail voice issued from inside: “Office hours are tomorrow!”

“It’s me.”

Sounds of thumping and shuffling came closer, and then Jane heard the rattle of a turning lock. The door fell open. “Hi, Dear.”

“Hi, Dad. I got your cookie.”

He extended a trembling hand and accepted the bag. “Thank you. I’m truly moved. Thank you.”

Harry Pool was seventy-three, hunched and frail. His face was blotched, his nose crooked, the result of a fall on the front steps of Seddon Hall three years before. Surrounded by books, as he was here, in his small, cluttered office, he should have looked like the platonic ideal of an elderly professor. Instead he resembled a defeated wizard or guru, a magician whose tricks have been rendered obsolete. He gestured toward the only other chair in the room, an industrial-looking armchair upholstered in cracked vinyl. Jane picked up the pile of books from it and moved them to the floor.

“Ah. Oh. Those. Yes,” her father said.

“How are you today, Dad?”

“I’ve run out of shirts, I’m afraid.”

“All right,” she said. “Are they in the bag? I’ll take them for you.” The dry cleaner was accustomed to rush jobs from Jane; her father tended to spill things on himself at work. The jackets were probably in even greater need of cleaning than the shirts, but brown tweed—in the feeble light from windows blocked by stacks of books—hid stains. They could always wait.

“Yes, yes. A student startled me.” He removed the cookie from its bag and began its slow and loving decimation. The empty bag fluttered to the floor.

“Dad. I have to tell you something. She emailed me.”

He gaped. Jane could see the partially chewed cookie.

She said, “Close your mouth, Dad.”

He nodded, swallowed. “Not—”

“No, not her. Lila.”

“Oh. What did she say?”

“Nothing. I mean, I don’t know. I didn’t open it.” Jane sipped her coffee. “Do you think I should?”

“Yes,” he said, but he was shaking his head no. “I don’t know. I would like to know that she’s all right.”

“When was the last time you heard from her?”

After a moment’s thought, he said, “It’s been a long time, Jane. More than a decade. Not since… before everything happened.” He looked up. “Has she contacted you? Before this?”

“Never. Not since I came back.”

“Mmm.”

They sat in silence, he eating, she drinking. After a while she rose, took the garment bag off the coat rack in the corner. She raised her coffee-and-scone hand in farewell.

“Please let me know,” he said. “If you do respond.”

“I will. If you really want.”

He took another bite from the cookie and nodded. He was staring at a spot on the wall now; he’d forgotten Jane and was thinking, no doubt, about her sister. She wordlessly greeted the former Soviet Union and slipped out the door.

She got through the day. The afternoon’s distraction was a pile of travel receipts from Dr. Lutherson, who treated most research travel as vacation time for herself and her wife, and never bothered to untangle which expenses were hers alone and which were incurred by Fiona. This always necessitated a long phone call or office visit, during which the professor would pretend not to have noticed the extra expenses, and Jane would pretend not to have noticed that she knew it all along. This time it was Italy. How many risottos dove la foresta incontra il mare scampi e funghi does it take to generate an endowed-chair-worthy monograph? Professor Lutherson seemed determined to find out.

When the clock read five minutes to four, Jane clicked open the email archive and selected the UK Rail message. She undeleted it. This time, she clicked the broken icon and loaded the image. It was a cropped jpeg of a page from a book, with a phone number added below the last line.

and flung her aside very roughly indeed; if they had been playing, such roughness would have made Bobbie weep with tears of rage and pain. Now, though, he flung her on to the edge of the hold, so that her knee and her elbow were grazed

1-877-883-4821

As the words sank in, she experienced a rising sense of anxiety and anger. Lila could have chosen anything from the book, but she chose this: siblings fighting on a boat. Did she even want Jane to call? Or did she just want to drive her further away?

Jane closed her eyes, drew breath, calmed herself. She printed the email, then rushed to the shared laser printer to snatch it up before anyone else got there.

Lydia was standing beside the machine, shrugging on her raincoat. “See ya tomorrow?” she said. Lydia was the calm, fiftyish single woman who figured out when and where all the classes should take place. Jane liked her workspace aesthetic, which was to cover everything with a shifting collection of different-colored sticky notes. Her desk was like a boulder overgrown with lichen and spattered with gull droppings. The paper emerged facedown into the tray, and Lydia watched Jane snatch it up and fold it discreetly in half.

“Bright and early!” Jane said.

Lydia glanced once more at the folded page and winked. “See ya.”

Back at her computer, Jane peeked at the printout, then permanently deleted the email. She said goodbye to Carmen, who always stayed a little late to wait for her boyfriend in another building, and walked to her car.

At home she found her mother-in-law playing Monopoly with Chloe. The triumphant look on Susan’s face was not, Jane surmised, a reaction to the game, but to her successfully appearing to have engaged Chloe in something “wholesome” and analog, rather than the video games or movies the child would presumably have been enjoying under Jane’s supervision.

“Sadly, dear, we’ll have to continue this another time,” Susan said with a sigh. “Your mother is here.”

“Come on, I’m about to win!” Chloe said. But Susan’s martyrdom could not be postponed. She got up and shouldered her purse.

Jane thanked Susan for picking Chloe up from the private school Susan paid for, half an hour’s drive from home. “Tomorrow?” Susan said.

“Tomorrow’s drama club after school. I can pick her up myself.”

“Very well,” Susan said, with a skeptical lilt. She was a resentful, calculating person who could display blithe condescension or strategic meekness, depending on the situation. She was the kind who entered a party with great fanfare but left without saying goodbye. Jane guessed she’d learned to be flexible while dealing with her now-diminished asshole of a husband. Or maybe she was just born that way and was the reason he was now diminished. It was no secret that she believed Chance could have done better. She was probably right. The two women glared at each other.

“So long, then?” Jane said.

“I suppose. Goodbye, Chloe! See you on Sunday!” A questioning glance at Jane, as if she might forget, or find some way to sabotage, the weekly extended family meal that, for Jane, was an excruciating waste of time, and which Susan imposed for this exact reason.

“Bye, Grandma,” the girl said, putting her colorful money back in the game box.

Susan clopped down the front walk, climbed into her Prius, and drove away, sitting straight-backed like an equestrienne.

“Mom,” Chloe said. “Take over, so I can win.”

Jane said, “I just got home. I need some time to myself.”

“You don’t have to talk to me. You just have to lose.”

With her wispy blond hair and long face, Chloe resembled her mother-in-law far more than she resembled Jane’s mother—although, old photos notwithstanding, it was difficult for Jane to conjure up her mother’s face. Often away and never truly present, Anabel Pool had left for good twenty years before. Jane’s canonical memory was of her trying not to betray emotion—usually irritation. Her signature quality was the effortful absence of feeling. Occasionally, in the couple of years after her disappearance, Jane would see something in her sister that reminded her of their mother—the way she got up out of a chair, or slipped quietly through a door in the dark—but now she hadn’t seen her sister in more than a decade, either, and her memory of both women was beginning to fade.

Jane sat down and let the girl beat her. She could see Chloe getting angrier as her Pyrrhic victory grew nearer, its pointlessness more clear. At some point Jane rolled the dice and accidentally moved her piece the wrong way around the board, and Chloe sighed. “All right, Mom, I give up.”

“Great,” Jane said, getting up. “I need to go on an errand.”

“I’ll come.”

“I need to do this alone, Chloe.”

“What, are you buying drugs?”

“Chloe!”

“Grandma thinks you do.”

“She said that?”

Chloe crossed her arms. “She said you get wild eyes, like you’re back on something.”

“Jesus.”

“Did you used to be an addict?”

“No,” Jane half lied. “The wild eyes are because of her.”

“Ha!”

The two faced off, staring, the girl’s head angled slightly, like a fawn that has heard a distant, suspicious noise. Now she resembled Chance, whose displeasure was rarely expressed in words. His tight vocabulary of gestures could convey, with masterful efficiency, precisely which of Jane’s flaws was bothering him.

It’s not their fault, she told herself. She did have many flaws.

“It’ll be boring,” Jane said. “Bring a book.”

Chloe hopped down from her chair and strode past Jane to the hallway, where she tugged her jacket down from its peg with a practiced snap of the wrist. “Where are we going?”

“The mall.”

“Where in the mall?”

“The parking lot.”

“That does sound boring. Why?”

“I have to make a phone call.”

“Use your phone!” she said, slipping the jacket on. She struggled, briefly, with the zipper. Jane watched her face as she considered asking for help, then rejected that possibility, then drew a sharp breath, then worked the tab into its slot and pulled it up to her chin.

“I need to use a pay phone. Maybe we can go inside for ice cream after. Isn’t there a yogurt place?”

“A pay phone? You are buying drugs!”

“I am not.”

“I don’t believe you.”

It wasn’t clear if Chloe was kidding or, if she was, how much. Now she reminded Jane of Lila—the unaffected bluntness that could be hostility or could be an ironic joke. They’d taken her to a child psychologist years ago—or rather, Chance and Susan had, at Susan’s insistence—to find out if the girl was on the autism spectrum, but it turned out she was just sarcastic.

“Whatever,” Jane said. “I need a minute. Meet me in the car.”

Jane went upstairs to the bedroom, opened the closet doors, and knelt on the floor. From a cardboard box behind the shoes, she produced a tattered paperback book: The Railway Children, a British children’s novel by E. Nesbit. It was about three children living in London in the early 1900s whose father, an employee of the British Foreign Office, is falsely accused of espionage and is arrested.

She remembered the scene Lila had excerpted: In it, the children are trying to save a baby from a barge that has caught fire. The bossy brother, Peter, tosses Bobbie, the eldest sister, to the side, trying to save the day. Sitting on the bed, book in her lap, it took Jane only a few moments to find the passage. She took a pencil from the bedside table drawer and worked out their code, jotting the results on the printout she’d made at work. Chapter 8, page 148, lines 22 through 26.

08 148 22 26

She put the book away, folded the paper around the pencil, and tucked them into the pocket of her dress.

They rode in silence. Their quiet neighborhood lay halfway between Jane’s job in Nestor and Chloe’s school in Rochester; the ride to the mall took them through the golf course, past several farms and the power station, past the nature preserve. The rain had been done for an hour, and sun appeared between speeding clouds.

The mall had been in decline for a decade; most people went to the mega-mall in Syracuse. The Old Navy had closed, then the American Eagle, then Best Buy. Only Target and the movie theater kept the place open. As she pulled into the parking lot and beheld its vast emptiness, Jane hoped the only nearby pay phone kiosk she could remember was still there.

It was. She found it outside the theater, amid the ragged-shrubs-in-white-gravel landscaping, beside the standpipe and wheelchair entrance. Part of her had wanted to just use her own phone, but she knew her sister would criticize her for it, or ignore the call altogether. She ought to have wanted to defy Lila’s preposterous, theatrical cloak-and-dagger nonsense, but her better angels held her back. Besides, she was curious.

She parked in the nearest space, about thirty feet from the phone. She said, “Five minutes.”

“Mhm.” Hair covered Chloe’s face; she licked her finger and turned the page of her book. Jane took a long look at her, then stepped out of the car.

The phone still worked. She dialed the provided number. While she waited, she spied a Target employee about fifty yards away, leaning against a red wall, smoking. A click gave way to a robotic voice that prompted her to enter the code.

08 148 22 26

“Thank you. Please wait.” The call cut off and the dial tone returned.

The hell? She replaced the receiver. Stickers on the phone’s casing advertised a strip club—correction, a gentlemen’s club—and take-out wings. A local band, a dog groomer. Had it been worth even the modest effort to stick the stickers here? Jane turned around, gazed again at the clouds. The Target employee threw her cigarette on the ground and returned to work. Her exhaustion and defeat were visible even from here—the feelings were infectious. Should she try again, or get in the car and leave?

No—the pay phone was ringing.

“Thanks for finding a pay phone,” said the voice on the other end. Her voice. Her twin’s. Lila’s. “I know you didn’t want to.”

“What do you want, Lila.”

“You have to come,” her sister said. “I think I’ve found her.”

There was no goodbye, not even a moment of realization that their mother’s absence was permanent. She just wasn’t around, as had often been the case, and then, instead of coming back, stayed gone. Their father never told them she’d left for good; maybe he didn’t know, either. Their mother was, as a rude parent of a friend once said to her years before, a rolling stone. Her parents’ marriage was a sham. There was never any point in wishing, waiting, or wondering.

The first time she disappeared, they were six and had stayed after school helping their teacher hang the harvest decorations in their first-grade classroom. This was supposed to be a privilege, because of their superior artistic skills. Jane was a little in love with their teacher, Miss Conover, who was cheerful and talkative and young. She always let them stay in the classroom during recess, silently reading while she painted her fingernails. Once she painted the twins’, too, and they wore the deep purple polish all day, until Miss Conover frantically rubbed it off in the last moments before the bus arrived. On this day, though, the three of them kept busy cutting red and orange leaves out of construction paper and compiling a list of words that evoked autumn: cool, dry, wind, branches, pumpkin.

After a while Jane noticed that Miss Conover kept glancing at her watch, and then at the clock above the chalkboard, then back at the girls. She peered out the windows overlooking the school parking lot, and out into the hall.

“Girls,” she said. “Will you behave yourself while I go talk to Mrs. Vainberg?” They heard her heels clicking away, down to the main office, and then returning a few minutes later.

“Is there a place where you think we can reach your mother?” she asked them.

Lila looked up, alarmed, at Jane. She set her scissors down. Jane turned to Miss Conover.

“At our house?”

“No one is answering there, or at your father’s office. She was supposed to have picked you up quite a while ago.”

“I’m sorry, miss,” Lila said.

“It’s not your fault, Lila. Perhaps she forgot that you were staying after today?”

Jane could remember their mother reminding them, that morning, that she would pick them up. “I don’t think so.”

“Do you think,” Miss Conover said, “one of your grandparents could pick you up?”

“We don’t have grandparents,” Jane said.

“Yes, we do,” Lila said. “They’re in Europe.” That’s what their mother had told them when they asked why they’d never met her mama and daddy. With a wave of the hand, as though she couldn’t care less. Their father’s parents, they’d been told, were dead.

“How about a neighbor? Does somebody live next door who could come for you?”

“We live in the woods,” Jane explained.

“Well,” Miss Conover said, “let’s wait a little longer, and I’ll give you a ride. Maybe there’s something wrong with the phone.”

Miss Conover’s car was extremely clean and had a sweet-smelling pine tree dangling from a knob on the radio. As they arrived at their house, she mumbled, “This is hardly in the woods,” and Jane realized, with a start, that she was right—their house was low, long, and sheltered by trees, but in a neighborhood of houses otherwise set closer together. You could even see the other houses from their yard. But Jane didn’t know who lived in them. She and Lila stayed in the yard and played with each other.

No one was home, but the front door was unlocked. The girls followed Miss Conover inside. Lila made peanut butter sandwiches, and Miss Conover politely turned down her offer of one. They sat in the kitchen until it was nearly dark. Then their father walked in, carrying his stained leather satchel bulging with books and papers.

“Oh!”

“Mr. Pool? I’m Fern Conover, the girls’ teacher.”

Fern! It had never occurred to Jane that she had a first name.

The adults talked, apologizing to each other. It was all a misunderstanding, they agreed. Their father rubbed his hands together as though it was cold inside, and hung his head. Miss Conover thanked the twins for their help and left, pulling the door gently closed behind her.

When she was gone, their father went into his office to make phone calls. The girls stayed in the kitchen, gazing at each other in alarm. They could hear his voice but not the things he was saying. After a while he came out, looking very tired. “Your mother’s away,” he said. “What do you—that is—it’s Friday. Are you hungry?”

“Can we have fish sticks?” Lila asked.

“Yes! But—I don’t—”

“They’re in the freezer,” Jane said. “You put them on a pan.”

“A tray. In the stove,” Lila said.

“The oven,” Jane clarified.

“The oven.”

The girls bathed and dressed themselves, told their father which books to read them, put themselves to bed. Their father seemed distracted and upset. In the morning, he wouldn’t come out of his room, so they ate toast and cereal and read and played with their dollhouse. Eventually it got warm out, so they went into the yard. Their clothes got dirty and their father didn’t seem to notice.

Their mother came back before dinner. She seemed tired and her eyes were red. She kissed them on their heads and went into her bedroom and closed the door. For a little while their father tried to talk to her through it, and eventually he went in and they argued. Then their father came out and ordered a pizza, and the three of them ate it. This time it was better. He oversaw their bath and picked the books to read. He remembered to make them brush their teeth. In the morning, everything was back to normal. No explanation was offered for their mother’s absence and they didn’t ask.

Normal, in their house, was a studious quiet—the sound of people indulging in their own preoccupations. The girls were expected to make their own fun. Their father, at his best, seemed gently amused by their existence, but they generally encountered him as he furtively retreated to his home office to work on the book he was perpetually a few months away from finishing. Their mother was more attentive, at least until a few years into her “times away,” which is what their father came to call these unexplained absences. Before, she had discharged the basic chores of motherhood with a wry, eye-rolling efficiency, always telling the girls how much they were inconveniencing her before dispelling their guilt with a smile and a wink.

Their mother winked a lot. She dutifully attended school functions—bake sales, choral concerts, the science fair—and winked at the fathers. The other mothers did not wink, and did not seem to like her. The fathers did. Jane had never seen other people see her mother until these events; she saw how people reacted. Their gaze lingered on her, their expressions changed. Her mother dressed differently from the others, whose attire was college-town casual—jeans, sneakers, university sweatshirts, and plaid flannels. Jane wouldn’t have known at the time what to call the clothes her mother wore, but from the few photos that remained, she could see that she was trying to look like Jean Seberg in a movie from the sixties—sleeveless dresses, floral cigarette pants, a man’s shirt tied at the waist. Headscarves and sun hats in the summer, long wool coats and fur-lined hats in the winter. Eventually, after she stopped attending such things, after she discovered her love of horticulture and spent what little time she was at home among her plants, she wore long khaki skirts or shorts, chambray shirts, vented leather clogs.

But for now, when they were small, she would respond to their attention, at first with resistance, even offense, before she capitulated, rewarding their persistence with stories of her childhood adventures in Russia or Spain, raised by servants whose care was easily escaped, wandering narrow cobblestoned streets, befriending stray cats and friendly shopkeepers, stealing lipstick out of tourists’ handbags and pastries off their tables. Only later would Jane learn these stories were invented, or at least greatly exaggerated; their mother had spent her childhood in the US and traveled to Europe infrequently, if at all.

The girls liked to be read to, but what they really liked was when their mother grew bored by whatever whimsical children’s story she was reciting and instead regaled them with these apocryphal tales. With the book abandoned, she could encircle Jane and Lila in her arms, tip her head back, beanbag ashtray balanced on the back of the sofa, and expel cigarette smoke into the air as she lied to her heart’s content. A standoff with a vicious guard dog, over which she triumphed with a poisoned sack of meat scraps. A necklace found in the gutter that turned out to belong to a dissipated heiress, who, in exchange for the lost item, taught her how to smoke. (“But you, girls, must never smoke. You shall not.”) A brooding Russian couple who kidnapped her, whom she escaped by leaping from their moving car into a river. A teenaged boy with a motorcycle who tried to rape her when she was ten, “but I crushed his jewels, girls, like my mother taught me, and I would have stolen them if I could.”

Years later, when the girls were ten themselves, Lila wondered aloud what this story meant.

“You don’t know what a rapist is?” Jane said. “It’s a man who tries to do it with you when you don’t want to.”

“I know,” Lila said. “I mean the jewels. How can you crush, like, diamonds? Or, like, if you can crush them, why can’t you steal them?”

They were sitting in front of the television. It was too late for them to be up, but their mother was halfway through another unexplained absence, and their father was locked in his office. Jane was half watching a James Bond movie, and Lila had a mat

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...