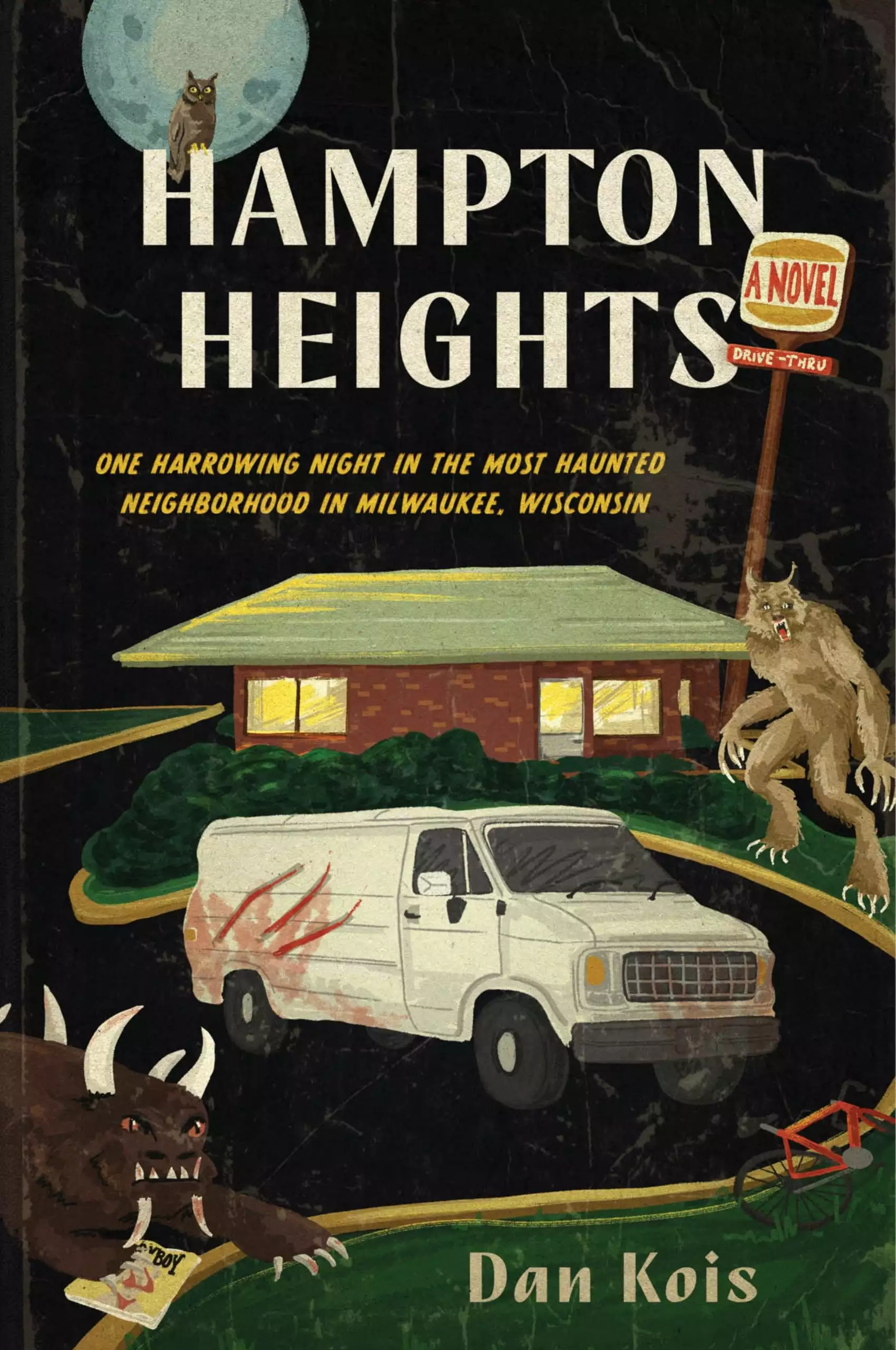

The Van

Later, when they talked about that night, the boys would say that the van must have been cursed.

The van certainly looked cursed. It was the species of long white panel van into which, traditionally, perverts lured children. It had no sliding door at the side, only swinging back doors that hung loose on their hinges, ready to fall open at the slightest acceleration. Ten years of hard driving through Wisconsin winters had eaten away at the van’s flanks, which were the dark gray of a smoggy sky and pitted with rust the color of dried blood.

The boys knew the van. Early mornings, eating cereal in the warmth of their houses, they heard the roar of the engine, the distant thump of hard rock. The papers were supposed to be there by five, but Kevin, their Milwaukee Sentinel delivery manager, always seemed to be a little bit behind. When they peered out their front windows into the predawn gloom, they could just make out Kevin throwing open the back doors and hauling a pile of newspapers to the porch. In the darkness he was a tall silhouette against the taillights. He wore a thin jacket no matter how frigid the weather. His cigarette glowed infernally.

They’d never seen the inside of the van—would never want to.

That van was evil, they said in later years, joking but not joking, when one saw another in a tavern, or when they reconnected on social media. In fact, the van was a miracle, as Kevin could have told them. It always started, even on the coldest morning. Its engine screamed like a Harley’s. It handled like a dream, considering it was basically a shipping container on wheels.

The van wasn’t cursed. That wasn’t the reason it all went down like that, that night in Hampton Heights.

The boys lived in neighborhoods scattered around the north and east sides, neighborhoods that were their responsibilities, their routes. Each morning when the boys woke to clock radios beeping or buzzing or playing “The Lady in Red” again their neighborhoods awaited them. They dressed in the light of bedside lamps, moved quietly through their houses to avoid waking anyone up. After Kevin dropped off the papers, they hauled the stack into the house, a block of newsprint still cold to the touch. They used scissors or a box cutter to snip the dirty yellow plastic cord that bundled them together. Each day’s Sentinel came in two sections, the front-page section and the rest, so they sat on the floor inserting one part of the paper into the other, sometimes getting distracted by a Peanuts or a Bucks photo or, less often, a news story. They checked the drop/add list for changes; they piled the newspapers in their cloth carrier bags; they made their way into the street as dawn began creeping into the sky.

The job made them tired all day at school and dirtied their hands with ink. Adults complained: The paper came too late, the paper came too early, the paper needed to be between the storm door and the main door, not just on the porch or, worse, at the end of the driveway. The job didn’t pay well at all. It was just the only job available to a thirteen-year-old who needed money.

But then the flyer appeared one morning, tucked under the yellow cord. Here was a different kind of opportunity.

EXTRA MONEY

FOR HOLIDAYS?

Canvassing Nights

December 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

6:00 PM

Space Limited, Sign Up Now

REMINDER!

All Paper Carriers

Must Canvass Once Per Year

Sell Subscriptions

Get Cash!

Dinner at Burger King!

Burger King! Sigmone Washington’s eyes went straight to the bottom of the flyer. Burger King was his favorite restaurant. His mom and dad loved McDonald’s, so there he was always eating those sad little beef patties when he could be eating flame-broiled. And it was free! Wait—was it free? The flyer didn’t exactly say.

Burger King! Ryan Sapp read it again in the porch light. Burger King! His parents disdained fast food, prided themselves on home-cooked meals. Every night at the table, his dad at the head, his mom running and getting everyone more salad, another glass of milk. He’d only ever had Burger King once, at his best friend’s birthday party, and it tasted so much better than those home-cooked meals that he would do anything to go there again.

Burger King! Kneeling in the front hallway, Mark Hoglund held the flyer in one hand, rubbed the back of his neck with the other. He could sell newspaper subscriptions. Lay on the charm, tell a few jokes, just like he did with teachers and parents and his church youth group leader. It was harder to be with kids his own age, especially girls; the ease he felt with grown-ups evaporated. But he had to try, because Burger King was where Heather Marchese worked. Heather Marchese who was a high-schooler, Heather Marchese who sat behind him every Sunday in youth group and, every Sunday, doodled on his neck in ballpoint pen.

Burger King! Alessandro Cotrone considered the flyer as he pulled on his coat, tied his scarf. A free dinner already, and cash to boot. How much cash? Probably that depended on how many subscriptions he sold. The question mark at the top of the flyer—EXTRA MONEY FOR HOLIDAYS?—was a tell, he suspected. It would require some real effort to sell those subscriptions, to persuade people to give money to a random kid standing at the door. But he’d done it before.

Burger King! Nishu Shah never got tired of watching the commercials on television: the gleaming patties flipping on a grill in slow motion, the flames flaring up, the vegetables cascading upon the burger in artful disarray. It would kill his parents to know how much their son wanted a hamburger. Before he showed the flyer to his mom, he took a pair of scissors out of the stationery drawer and cut off the last line.

Burger King! Joel Taylor, reading the flyer in his house’s cavernous entryway, hoped they would eat first and then sell newspapers. A big fast-food meal would generate incredible material for his fart tape.

Now the van was

back, idling at the curb on a December evening. Whatever was hidden in its depths, the boys were about to see it.

“Baby,” Sigmone’s mom called from the living room, “the man’s outside waiting for you.” He finished tying his shoes and kissed her goodbye. On the wall by the front door, his grandfather smiled from the photo, a young Sigmone grinning on his lap. He picked his way down the icy steps to the ground floor of the duplex.

He usually avoided going out after dark, worried about the knuckleheads just a year or two older who spent the nights getting into trouble, but tonight no one was around. The van idled by the corner of Holton and Concordia. The clouds were fat and blank, illuminated from below by the lights of the strip a block away. It was going to snow tonight, he could tell.

Kevin had a thick mustache, a long brown mullet, and little eyes scrunched into his face. He was drumming on the steering wheel and jumped when he noticed Sigmone waiting outside the passenger door. He reached across to roll down the window. Sigmone had never met Kevin in person, only talked on the phone. He guessed his manager was forty or something.

“Kids in the back, man,” Kevin said, pointing over his shoulder. “It’s unlocked.”

The double doors opened with a groan. Inside it was nearly empty, it turned out. There weren’t even any seats behind the driver’s row, just the steel floor and the wheel wells on each side. Kevin’s hard rock music filled the stale air. Scattered around were loose pages from, Sigmone assumed, centuries of the Milwaukee Sentinel.

“You gotta really slam those doors,” Kevin called from the front. Even after he pulled the doors shut, Sigmone could still see street light between them, and he sat as far to the front of the truck as he could, his back against the passenger seat, bracing his feet on a wheel well. Somehow, when Kevin accelerated, the doors stayed closed.

Craning his neck, Sigmone could see they were driving north, toward the suburbs. The route was the same as the number 15 bus he took every morning, so Sigmone assumed the other kids they were picking up would be white. He prepared himself for the expressions that would flash across their faces when they opened the doors and saw him.

Ryan saw the van from his window when it pulled up outside his house. His mom joined him. The street was dark enough that they could see themselves reflected clearly, their near-identical faces, his eyes still well below hers.

“You’ll be careful?” his mom asked.

“It’s fine,” he said, zipping his coat.

“I wonder where the other boys will be from,” she said.

“They’re just other paperboys,” he said. “We’re not gonna be lifelong friends.” He saw her carefully not respond, saw her reach out for a hug. He squirmed away. They must have been lit up like a movie

screen in the window.

On his way down the sidewalk, the salt his dad had made him scatter in anticipation of snow crunched under his feet. Kevin gestured toward the back, and when Ryan wrenched the doors open, he revealed a lone black kid sitting on the floor. The kid was big, way bigger than Ryan, but he looked so miserable wedged up against the passenger seat that Ryan could hardly be intimidated. Though he hardly ever talked to the few black kids at his school, he managed to squawk out a “Hey.”

The boy nodded. Ryan closed the doors, opened them, tried closing them again. He said, “Are these, like, actually—aahhh!” For that was the moment when Kevin hit the gas. Ryan tumbled into the doors, which gave, sickeningly, just an inch—but held. He shrieked, he knew, the noise that always made his dad wince.

The black kid was kind enough to pretend not to notice the sound. “I thought you were going out” was all he said.

“Oh my God,” Ryan said, scrambling forward as the van bumped along the road. “Oh my God.”

Mark was watching TV in the family room when he heard the horn. He checked himself in the foyer mirror: his Ocean Pacific sweatshirt, his freshly cut hair. “Yeah, make sure you look good,” his brother said from the top of the stairs. “For when he molests you.”

“Shut up, dick.” Danny had been a paperboy, too, when he was Mark’s age. He’d gone out canvassing, come back rolling his eyes. It was impossible to sell subscriptions, Kevin was a creep, and so on. Mark was pretty sure the problem was that Danny was a dick. In a moment of weakness, he had once asked Danny if he thought Heather Marchese liked him. “No,” Danny had said. “You’re a shithead.” Now Danny worked at Kopp’s Custard, where every time Mark showed up Danny pretended not to know him.

But it had to mean something, right? Heather Marchese was funny and cute and she always sat in the chair behind him, every Sunday. And every Sunday he felt the cold tip of her ballpoint on his neck. After the first time it happened, he recalled, he’d spent five minutes in the bathroom at home, angling his mom’s hand mirror, trying to get a glimpse of what she’d written. He was afraid it was something mean, KICK ME or something, but when he finally caught the image, he saw she’d drawn a delicate vine creeping up his neck, a flower sprouting from its top. The thought of talking to her at Burger King made him feel sick, but he also couldn’t wait.

The horn blared again. Mark flipped his brother off and ran out the door, pulling on his coat as he went. There were two other kids in the back of the van: a tall black kid and a short, chubby boy with freckles. “Sorry it’s so cold back there,” Kevin said as he threw the van in gear. “Heater’s on the fritz.” Neither of the kids was talking, and Mark always felt like it was his job to get people talking, so he said, “I’m Mark. Who are you guys?”

They were Ryan and Sigmone. On the way to the next house, Mark and Ryan talked about Weird Al Yankovic.

Al had considered asking Kevin to get picked up somewhere else, Food Lane maybe, so the other kids wouldn’t see him coming out of his town house. When kids at school learned he lived here, they put on an apologetic facial expression, as if they’d learned he had a childhood disease. The town house was perfectly nice, his mom told him, and he knew she was right, but that didn’t stop him from feeling bad when he saw the kinds of houses his classmates lived in.

But as he approached the van, he saw that all the other kids must be in the windowless back, from which loud noises emanated. When he opened the doors, he revealed two boys singing at the tops of their lungs. “Dare to be stupid!” they shouted, laughing. A black kid watched them warily. None of them, he realized, could see the town house, none of them even cared about where he lived. No one is thinking about you as much as you think they are, his mom had told him once.

One of the boys asked Al his name, then cheered when he said it. “Weird Al!” they shouted. Al felt his face heat up as he clambered into the van, but he’d take it. He pushed himself against the wall and nodded at the black kid, whose name was Sigmone. The other white kids, Mark and Ryan, went on singing. If he listened carefully, maybe he could learn the words.

Nishu’s mom didn’t want him to go. “He’ll be too frightened,” she said. His dad was exasperated, he could tell, but was trying not to show it. Instead he reminisced about all the weird jobs he’d worked when he was young: valet, fisher, assistant in his uncle’s shipping office. Most of the time Nishu felt no desire to go to India, but the idea of a country that would let a kid do all that made him laugh. Here all he was allowed to do was deliver newspapers.

“Don’t you remember the movie?” his mom asked. They had all gone to E.T. together, and Nishu, scared of the doctors in the astronaut suits, had hid under his chair. That was five years ago.

“That was five years ago!” his dad said.

“We don’t even know this Milwaukee Sentinel person,” she said.

The van pulled up and Nishu grabbed his backpack. “I have my homework,” he said, “we’ll be done at nine,” and charged out the door.

In fact, his mom had met Kevin before, when she demanded to interrogate him before she would let Nishu start delivering papers. (She said he seemed like an idiot.) That had been embarrassing, but not as embarrassing as his mom now shouting out the front door, “Buckle your seat belt, Nishu!”

Kevin tried to wave Nishu to the back but Nishu stood miserably at the passenger window. Kevin rolled it down and smoke billowed from the van. “Can I sit here?” Nishu asked.

“Is he smoking?” his mom called.

“Sorry,” Nishu added.

Kevin flicked his cigarette out the window, past Nishu’s ear, and waved cheerily to Nishu’s mom. “Sure, yeah man, no problem,” he said.

“Just move that shit down there.”

The seat was covered with notebooks and pens and clipboards and—oh, wow, this was a big knife. Nishu piled them all up and placed them on the grimy floor of the van, then set the knife, tucked in some kind of scabbard, atop the pile. Then he put his backpack on top of the knife. Even when he buckled up, his mom wouldn’t leave the front door. Finally Nishu muttered, “Just drive, please,” and Kevin peeled out with a sound he knew his mom would talk about for weeks, maybe years.

At the sixth and final house, Kevin had to pull up to a gate, roll down the window, and announce himself to an intercom. From the intercom came a squawk. In the front seat, Nishu said, “A kid lives here?” He turned to address the four boys in the back: “You gotta see this. It’s like a castle.” The other boys shoved the back doors open and clambered out to behold: It was a castle. A long driveway led from the gate to a massive cream-colored mansion, as big as a movie theater. Floodlights on either side of bright red double doors picked out the half-dozen columns reaching to the roof.

“Is this . . . Lake Drive?” Al asked. Everyone knew Lake Drive was where the mansions were.

“I think so,” said Nishu.

One of the doors opened and a figure in a blue coat hurried out. Lit now by the floodlights like a burglar caught by the police, the figure stopped, went back into the house, and in a moment reappeared carrying a big green backpack. The boys stood in silence for the long minute it took the kid to trudge down the driveway. He pushed the gate open and stepped through. The gate closed behind him with a gentle clang. As if coming out of a trance, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved