- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

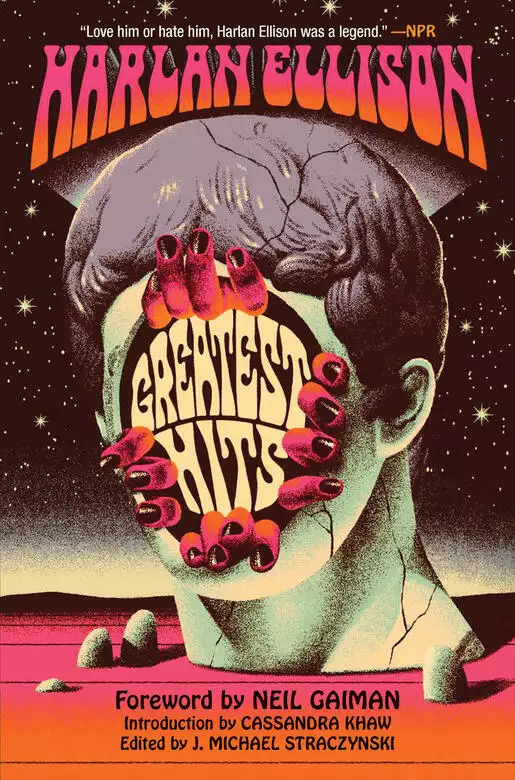

A collection of award-winning short stories, including the viral “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” by Harlan Ellison, an eight-time Hugo Award winner, five-time Bram Stoker Award winner, and four-time Nebula Award winner.

Featuring these stories and many more:

- “‘Repent, Harlequin,’ Said the Ticktockman” — Hugo Award winner

- “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” — Bram Stoker Award winner

- “Mefisto in Onyx” — Bram Stoker Award winner

- “Jeffty Is Five” — British Fantasy Award winner

- “Shatterday” — Twilight Zone episode

- “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs” — Edgar Allan Poe Award winner

- “Paladin of the Lost Hour” — Hugo Award winner, Twilight Zone episode

A must-read for sci-fi book lovers and fans of Ray Bradbury, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Isaac Asimov, this career-spanning compilation of classic short stories is also perfect for readers who enjoyed Dangerous Visions, A Boy and His Dog, or other Harlan Ellison books.

Release date: March 26, 2024

Publisher: Union Square & Co.

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Greatest Hits

Harlan Ellison

In his stories of fantasy and horror, he strikes closest to all those things that horrify and amuse us (sometimes both at the same time) in our present lives.… Ellison has always been a sociological writer … [who was] pro-choice when it comes to abortion … [and] an affirmed liberal and freethinker.… Most of all, we sense outrage and anger—as with the best Ellison stories, we sense personal involvement, and have a feeling that Ellison is not so much telling the tale as he is jabbing it viciously out of its hiding place. It is the feeling that we are walking over a lot of jagged glass in thin shoes, or running across a minefield in the company of a lunatic. —Stephen King

Categories are too small—even the catch-all category of science fiction— to describe Harlan Ellison. Lyric poet, satirist, explorer of odd psychological corners, moralist, one-line comedian, purveyor of pure horror and of black comedy; he is all these and more. —The Washington Post

A furiously prolific and cantankerous writer (who) looked at storytelling as a “holy chore,” which he pursued zealously for more than 60 years. His output includes more than 1,700 short stories and articles, at least 100 books and dozens of screenplays and television scripts … ranked with eminent science fiction writers like Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov. —The New York Times

Harlan Ellison was, after all, one of the most interesting humans on Earth. He was one of the greatest and most influential science fiction writers alive. He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma, lectured to college kids, visited with death row inmates, and once mailed a dead gopher to a publisher. Ellison brought a literary sensibility to sci-fi at a time when the entire establishment was allergic to any notion of art. To say he was one-of-a-kind would be trite, and he would likely hate that. What he was, was a legend. —NPR

[Harlan] was very influential in changing the field, making it more open to social issues, to explorations of characters. He’s had an enormous influence on science fiction with his writing, and he’s also been an influential editor … setting an agenda for a new kind of science fiction writing that would be more socially engaged and responsive to the times. —Jeff Lathan, Science Fiction Studies

There’s a real power to the way he uses the language and how he draws pictures in your mind. —Ron Moore

You see Ellison’s unswerving social conscience throughout his fiction and critical essays … forcefully and eloquently—and at some length—lamenting the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment and railing against the scourge of misogynistic “knife-kill” films. —Rogerebert.com

The words—there is an attention to the words. There is an attention to the sound of the words. You’re reading them in your head, and they sing. —Neil Gaiman

The spellbinding quality of a great nonstop talker, with a cultural warehouse for a mind. —The New York Review of Books

Feisty, furious, yet extraordinarily kind and generous; Harlan Ellison was one of a kind. —Leonard Maltin

Harlan Ellison—terrific prose, razor-sharp intellect, pulp gut punches and invention when needed, terse poetics … an original. —Guillermo del Toro

An original and valuable writer … a twentieth-century Lewis Carroll. —The Los Angeles Times

Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, stand aside. Harlan Ellison is now a better short story writer than you will ever be again during the rest of your lives. —Ray Bradbury

The incredible Harlan Ellison writes as if an inner fuse is about to blow before he can get all the words on his pages. —Anne McCaffrey

He doesn’t write like anybody else. What emerges is a surprising, eclectic, almost protean series of visions, often disturbing, always strongly felt. —Michael Crichton

Harlan was not just a great fantasist and/or science fiction writer; he was a great writer, period. When he was at the top of his form, there was no finer short story writer in all of English literature. [He] had an enormous influence on the writers of the generation that followed, my own generation. He fought for racial equality, marching with King at Selma. He fought for women’s rights and the ERA. He fought publishers, defending the rights of writers to control their own material and be fairly compensated for it. He was a hero to us. —George R. R. Martin

J. MICHAEL STRACZYNSKI

HEY, YOU!

Yeah, you!

I feel your pain. I know what you’re going through.

You’re thinking, How could it be that I, a traveler in all the deep places of the world, who knows the secret password to the hidden city beneath Jakarta, who has traveled with monks and prophets from a dozen countries, who possesses enlightenment and wisdom far beyond my years that I have used to defend myself against assassins sent (futilely) to ensure that my knowledge went no further, how could it be that I have not previously heard the name Harlan Ellison?

You’re thinking, How is it possible that I, a bon vivant revered by presidents and popes and politicos, invited to all the best parties (including the ones no one is supposed to know about) (especially those) where the arts are favored above all things, had not been briefed on the works of an author who wrote over 1,700 short stories, novellas, television episodes, and critical essays, along the way earning more awards, and more kinds of awards, than any other writer, living, dead, or zombified?

You’re thinking: How could someone who is as politically savvy and socially aware as myself, who embraces battles against censorship, misogyny, racism, and the other sociopolitical evils that have braced us up against the wall for far too long, have missed the stories of someone who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, fought for feminist causes, went to war with networks and publishers over censorship, and who appeared regularly on talk shows and college campuses to rail against corporate greed, the exploitation of artists, political corruption at the very highest levels, and was on the Enemies List of at least one United States president?

But mainly, you’re thinking: Are the rumors true he was a snappy dresser and a damned good dancer?

Yes … yes, they are.

And there’s a reason you haven’t come across his name before.

Harlan was an iconoclast, a troublemaker, a rabble rouser, and a force of nature, but above everything else he was an artist armed with a very clear vision for the ways in which his work was to be published, from the cover art down to the font, the paper stock, and the smallest nuance of punctuation. While some publishers accommodated that vision, it was always a struggle, and the victories were endlessly complicated by publishers, agents, and random amanuenses (amanuensisis? amanuensii?) who didn’t understand or simply didn’t care what was required of them to preserve the integrity of the books, and thus just did whatever they wanted. Harlan’s battles for literary freedom, and against corporate stupidity and cupidity, were legendary.

But also exhausting.

You try being a Force For Good In Your Time. After a while even the most determined of us would like a day off to sit in the sun and read a book. (Come by the house sometime and I’ll tell you the story about Harlan, an errant publisher, a dead gopher, 213 bricks, Donny Osmond stationery, and a Lithuanian hit man.)

Rather than waste time, energy, and visceral material on battles with publishers, resources that could be better used to Fight The Good Fight against censorship and other causes Harlan supported, Harlan began putting out his work in limited editions that allowed him absolute control over the product from end to end. They were so magnificent, so beautiful, that the few copies remaining out in the wild routinely sell for thousands of dollars.

But for Harlan, it wasn’t about the money. Which is not to say money isn’t a good thing, or that writers shouldn’t get paid (another ongoing battle), only that if you’re any kind of artist, the primacy of the work has to come first. Because once you’re in the ground, nobody cares how much money you earned, what kind of car you drove, or how dashing you looked in a Borsellino hat cocked at exactly the right rakish angle. All that remains is the quality of the work, because that’s the only thing that survives the life of the artist.

See, Harlan was an atheist. He didn’t believe in an afterlife where we would find redemption or expiation for the mistakes and casual cruelties we’d committed in life. He believed it was essential to stand up for the betterment of the human species rightdamnitnow, not in the unknowable void on the other side of death. So he put his money, his safety, and in some cases, his life where his convictions were. He advocated for civil rights and gun control at a time when those were dangerous things to do, leading to (a) the time someone took a shot at him onstage while he was speaking against gun violence, and (b) the proudest moment of his life when he marched side by side with Martin Luther King Jr. at Selma. He worked ceaselessly with PEN International, an organization dedicated to the fight against censorship around the world, which recognized his work with the Silver Pen Award.

Harlan was also a fierce feminist who worked hard to raise the profile of women writers in the science fiction genre at a time when it was dominated by male writers, with Octavia Butler as just one example. But his commitment went far beyond being simply an ally and advocate. In 1978, during the height of the struggle to get the Equal Rights Amendment passed (a struggle that, sadly and unbelievably, is still going on today), Harlan was invited to be guest of honor at a huge SF convention in Phoenix, Arizona. When Arizona voted not to ratify the ERA, and the National Organization of Woman declared an economic boycott, he decided that rather than not attend, which would disappoint thousands of fans, he would instead execute a one-man boycott to ensure that he did not spend so much as a penny in Arizona. He rented an RV, filled it with snacks and tons of bottled water (he was a lifelong nondrinker), and drove from Los Angeles to Phoenix, gassing up before crossing the state line. He declined to accept the offer of a hotel room, which would have been paid to the hotel by the convention, and spent the hottest weekend in the hottest summer Phoenix had experienced in years living out of that tiny RV, during which he worked closely with NOW to get press coverage for the boycott of Arizona and the reason it was necessary.

For Harlan, what someone said they believed was never the point. The point was the degree to which they were willing to put skin in the game, to take a stand that carried risk, to stand when standing was the hardest thing in the whole world. That’s when you know who you really are. So he didn’t just speak out against racism and misogyny on college campuses; he took that into corporate boardrooms, the streets of Selma, and the offices of network executives. Didn’t matter if he lost work as a result. It was the right thing to do, so he did it. The same rule applied to his work. He brought controversial, progressive themes into his stories in ways that no one had even thought about doing before, a stance that led directly to the birth of New Wave Science Fiction, which forever transformed the genre.

All of which is a very long road to answering the questions posed at the top of this preface: The reason you haven’t heard of Harlan Ellison is that after living that life and doing those remarkable things, he spent the last three decades of his life in a J. D. Salinger–esque exile from the world of mainstream publishing. It was during this time that I came to know Harlan as a friend, though I’d known him through his work for many years during which he was, all unknown, a long-distance mentor to my own writing. His courage and his tenacity strengthened me, his wisdom humbled me, his loyalty inspired me, and his eccentricities maddened me but never pushed me away, because in all things and at all times, his heart was forever in the right place.

Now, with his recent passing, which led to my being named executor of the Harlan and Susan Ellison Foundation, it’s time to reintroduce the world to a collection of his most powerful, vibrant, and often controversial stories, tales that are as challenging now as they have ever been, and perhaps even more relevant.

These are stories of wonder, loss, love, longing, terror, and laughter, written by a fierce intelligence dedicated to the proposition that we can, and should, be better than we are.

Most of all, they are stories with teeth. Even the funny ones.

Especially the funny ones.

You have not heard of Harlan Ellison before.

And that’s okay.

Because the voyage into the unknown worlds he created begins again, right now, on the other side of this page.

Bon voyage.

NEIL GAIMAN

To prepare for this introduction, and because I missed him, I listened to Harlan Ellison reading Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. On the one hand it was like having him back—hearing his voice, the precision and enunciation, the glorious delivery. His astonishing reading ability, and the feeling that the words were in his blood. And on the other hand … he had decided to cast it with his impressions of actors from the golden age of Hollywood—W. C. Fields was Tweedledum, the White Knight was Peter Lorre, and I was baffled, except that I wasn’t. They are excellent impressions. Harlan was obviously very proud of them and wanted a record of them for posterity, even if they seem completely unsuited to the material. And I smiled, because that was the most Harlan thing of all. Harlan giveth; Harlan does a weird but impressive thing that probably works against him.* That was his life and career in miniature.

So.

I met Harlan Ellison the person in 1985 in the Grand Central Hotel in Glasgow. He was guest of honor at a science fiction convention. I went to Scotland to interview him for a British SF magazine, which was canceled before the Harlan issue went to press.

I met Harlan Ellison the writer when I was only a boy: I read short stories that ripped my mind open and showed me what the possibilities of fiction were, what you could do with just words. They seemed different to the stories around them—full-color explosions that, somehow, changed me. I was not the person I had been before I read the stories.

I read “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ said the Ticktockman” and “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” both in the Best SF anthologies, when I was about eleven, although I knew already that Harlan existed, because James Blish had written about Harlan in his second Star Trek short story collection—Blish had talked about Harlan and about adapting his Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever” into short story form.

As time went on, I bought anything by Harlan I could find, cheap remaindered imported paperbacks with titles like From the Land of Fear or The Time of the Eye. I read library books, finding stories by Harlan in anthologies, each one making me feel like a prospector who had found a hidden golden nugget. Unable to obtain the landmark Dangerous Visions anthology that Harlan had edited, I bought a copy of Dangereuses Visions while on holiday in France and read it in schoolboy French as best I could.

Harlan’s work, as a screenwriter, an editor, and most of all, as a writer, of fiction and of nonfiction was inspiring to me as a boy and as a teenager. I didn’t have a route map to becoming the kind of writer I wanted to be. I didn’t have a teacher. But I had Harlan’s introductions and his articles, and more than that, the evidence of his life and career to demonstrate that it could be done. Harlan had written comics and scripts and prose; he read his own stories better than anyone else could read them. When I was twenty-one I had the worst day of my life up to that point. And the only thing for sale at the airport, as I was to fly home and try and put my life back together, was Harlan Ellison’s Shatterday. It, and the essays in it, before each story, were what made me believe I could become a writer. That I had to do the work.

I arrived in the world of Fantastic Literature in September 1983, as a young journalist sent to cover the British Fantasy Convention, there to interview Robert Silverberg and Gene Wolfe. I remember sitting next to a prominent literary editor at the awards banquet. He asked me about writers I liked, and I mentioned Harlan. The editor explained that Harlan had now demonstrated he was never going to write a major novel, which meant that he was irrelevant. I didn’t even know how to argue. I felt like I’d been told that a miniaturist did not matter because they did not paint murals. Harlan mattered. I was certain of this.

Harlan and I slowly became friends, and I loved being his friend, even if sometimes it felt like I had been befriended by a hand grenade. I could only hope that if he was to explode, I wouldn’t be there.

He would sometimes leave angry but eloquent messages on my answering machine: “Gaiman. This is Ellison. You are a dead man. I will be sending a missile to take out your house. I will sow salt on the rubble where your house once was to make sure that nothing ever grows there again. I will curse your house and line with a thousand maledictions and imprecations, and you and your children and your children’s children will be immolated and forgotten. Call me!”

(I did. That time Harlan chewed me out for having given a journalist his phone number. I pointed out that I hadn’t; I had instead mentioned to the journalist that, as Harlan would often tell people in his introductions, his number was in the phone book. He said, “Fair enough,” and changed the subject.)

And now Harlan’s dead and gone, and I miss my friend. (I miss my friend’s gentle, sensible wife, Susan, too. She met him at the same convention I did in Glasgow in 1985, but she married him, and kept him as sane as she could and as grounded as she could.)

I miss my infuriating, brilliant friend—he of the stories that might have been true, or at least trueish, and were sometimes truer than anyone else believed. He was, I sometimes thought, putting on for the world a piece of performance art called Harlan Ellison. And none of it would matter if Harlan hadn’t written some astonishingly brilliant stories along the way—coruscating, fizzy fireworks, written at white heat, pounded out on a manual typewriter.

I like to think Harlan would have approved of this book, because it’s all about the stories, and an excellent selection it is, too. It covers Harlan’s peak creative years and selects judiciously from his later career.

There’s a story in this book called “All the Lies That Are My Life.” It’s a fantasia about the death of someone who is a version of Harlan as he might have been if he was A Great Man, that is, at its core, about the fear of being forgotten—the fear that Harlan had that his stories, which were his children, would be swept away in time. That he would become one with Thorne Smith or Gerald Kersh or any of the other writers who were, for a moment, here, and who, for a heartbeat, mattered, but whose words were mostly forgotten and who had become footnotes in dusty reference books.

These stories, I hope, and this book, will help keep Harlan’s memory bright. They were typed at white-hot speed on a manual typewriter (Harlan typed, he said, too fast for an electric typewriter), many of them written over fifty years ago. They tell us important things about society and bravery, about pain and identity, about death and evil, about love and responsibility. They are stylistically diverse, always ambitious. Some of them are pretty funny, too (and some of them are dark and painful as hell). With an impressive mixture of narrative choices, intentions, emotional resonances, these are stories that show off for you a few of the things that Harlan could do: it’s hard to compare a story like “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” with its Shirley Jackson–inspired Levendis (is that his name or his exhortation?) showing us the meaning and meaninglessness of history and free will, with the nightmare of AI and inhumanity that is “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”; to contrast the heartbreaking nostalgia of “Jeffty Is Five” with the dystopian Harlequinade of “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ said the Ticktockman.”

Like all art made in this world, they are stories of their time. And when you are talking about Harlan Ellison, they barely touch the surface of what he made (there are two Essential Ellison collections, each over a thousand pages long). But everyone must start somewhere. And this is a fine place to start.

I hope they change you.

* Or maybe not. His reading of Through the Looking-Glass was nominated for a Grammy Award, after all.

CASSANDRA KHAW

When I think of anger, I always think of Harlan Ellison’s AM. For all the dystopian fiction I’ve consumed, all the books about monsters, nothing has come closer to depicting a perfect, insoluble fury better than the deranged supercomputer at the center of Ellison’s seminal “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.” I don’t remember if I enjoyed that first read, but I remember being struck by how bleak the story was, how AM burned with wrath, how it hated the fact it’d been given all the intelligence in the universe but no way of experiencing existence sincerely—that it had been created to serve and nothing more.

And I was struck by how much I understood.

I was a closeted queer kid raised by very traditional parents, parents who struggled with both their unresolved traumas and their conservative upbringings. On one hand, they wanted nothing more than a stellar career for me, a good life, autonomy, every opportunity in the universe. On the other hand, I was beaten senseless for even the smallest infractions because anything less than perfection was a monstrous offense. I was told from a young age I was born to be of service to my parents, alive only because I had a function to fill.

Surprising no one, I grew up angry. I also grew up quiet and absorbed in books; I spent at least a few years of my life reading the dictionary from back to front for the sheer pleasure of the words. It’s no surprise the school bullies took an interest in me—which was a terrible mistake on their part. I was a scrappy kid who threw down with everyone who took a swing at me.

For a long time, I didn’t know why I was so incandescent with rage. Only when I got older did I understand it was fury at how unfair the world was, how cruel it sometimes chose to be, how utterly repellent it was that the people who should have protected a child saw fit to use them as a punching bag instead. There’s a certain atavistic truism that every abused kid learns: You’re either the one doing the beating, or the one being beaten. If you’re unlucky, you crawl out of childhood so full of pain, all you can do to keep yourself sane is spread it around.

Some of Ellison’s bibliography feels like he’s writing to process this aphorism. “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs” envisions a nightmare caricature of a world where to survive, one must choose to participate in pain. It’s almost exaggeratedly cruel, filled with an idiot animal evil. Surely, we’re not like that in real life. And yet, sometimes we are.* Sometimes, we freeze. Sometimes, we look away, click away, avert our eyes, because the alternative is risking being hurt. You can feel the depth of Ellison’s anger at this, his grief, his awareness of what time and fear claw from us.

This book is structured around those elemental forces that drove Ellison: Angry Gods, Lost Souls, the Passage of Time, the Lighter Side, the Last Word. You can see these forces at work in my favorite stories in this collection: “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” radiates his anger at how we are all driven relentlessly to greed, hoping beyond hope for a payoff when, really, there’s nothing waiting for us but death at the top of the mountain. (A gut punch to reread as a freelance writer, honestly.) “Jeffty Is Five” is an unsettling look at the loss of innocence and how hard it is to hold onto the past as you age into a stranger; not an easy read for someone on the cusp of middle age. “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman” is a standout with its stream-of-consciousness prose, darkly hilarious moments, and its furious, absurd take on our time-is-money culture and the pointless regimentation of our lives.

Yet there’s also a sense that Ellison wanted more of our species, that under the grinning cynicism and the incandescent fury, there was someone who would have been thrilled to be proven wrong about the world. Even one of his most violent stories, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” for all its bleakness and lavish brutality, reminds us that kindness—true kindness, true sacrifice, true charity—is possible, even if it costs us everything. In reading Ellison’s teleplay for the Twilight Zone adaptation of “Paladin of the Lost Hour,” a story about a friendship that spans gender and race, I was struck by the unbearable gentleness of its final lines:

Like a wind crying endlessly through the universe, Time carries away the names and the deeds of conquerors and commoners alike. And all that we were, all that remains, is in the memories of those who cared we came this way for a brief moment.

We are those who loved us and whom we loved in turn. So why, Ellison seems to demand, are we such fucking degenerates to one another?

In many ways, his life can be read as a response to this question. An unrepentant firebrand, Ellison was a ferocious advocate for whom and what he believed in, using his brazenness as a cudgel to clear a path forward for others. He furiously championed writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel Delany, and Octavia Butler in a time when diversity in the genre was all but nonexistent. He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. at Selma; he spoke openly against the Vietnam War. Ellison also used his bully pulpit as a reviewer for the Los Angeles Free Press, and his time during TV interviews, to go to war over the treatment of women in slasher movies (at one point nearly coming to blows with a director at a Writers Guild screening over that kind of portrayal). He stood by his beliefs; Ellison famously coordinated with the National Organization of Women to draw media attention to Arizona’s failure to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

Yet, seemingly more than happy to live up to his own notoriety, Ellison was unapologetic about his thoughts and often shocking in his behavior. His depiction of women, despite his avowed feminism, often walks a fine line between critiquing and indulging misogynistic tropes. The novella A Boy and His Dog, which is not part of this collection, is a post-apocalyptic dystopia with frank depictions of male and female rape that still make me wince. I don’t think we needed to know how badly Beth hated the sex in “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” or to have Ellen, a Black woman, become the group’s sexual plaything in “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream.” Do I understand Ellison’s narrative decisions, the points he was trying to make? Yes. But I still believe he could have made better choices; a belief that holds especially true for his 2006 Worldcon speech with Connie Willis, who deserved so much better.

Reading this collection reminded me that Ellison’s rage once provided me with instruction, showing me that you can use your pain and anger as a light. Pain, especially when you carry it in your ribs next to your heart, can teach you an unbearable amount of compassion, because it has left you too flayed for pretenses. Looking back at Ellison’s storied life, I think he used that welter of inner pain as best he could: He turned it into fuel for creation and fuel for his activism.

Harlan Ellison was a troubled, complicated, and occasionally infuriating man, but he was nonetheless a light. I hope that in reading these stories, in reading J. Michael Straczynski’s preface and Neil Gaiman’s foreword, you see all sides of Harlan Ellison, good and bad, illuminated.

* The story was written in response to the death of Kitty Genovese, a twenty-eight-year-old bartender whose brutal murder was reported to have been witnessed and ignored by thirty-eight people, though this was later disproven.

There are always those who ask, what is it all about? For those who need to ask, for those who need points sharply made, who need to know “where it’s at,” this:

The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies. They are the standing army, and the militia, jailors, constables, posse comitatus, etc. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw or a lump of dirt. They have the same sort of worth only as horses and dogs. Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others—as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and officeholders—serve the state chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the Devil, without intending it, as God. A very few, as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men, serve the state with their conscience

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...