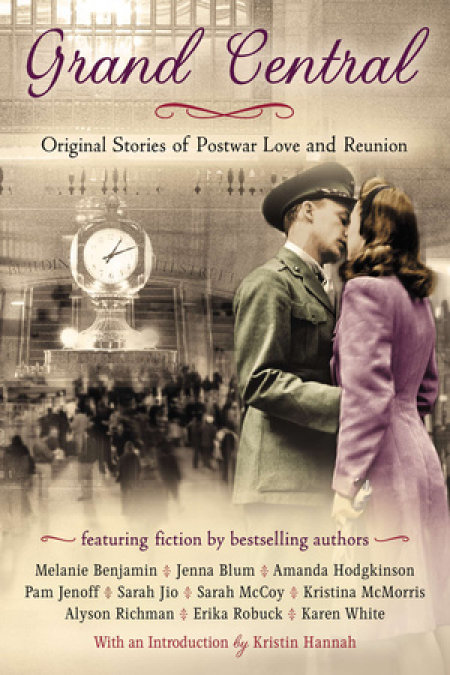

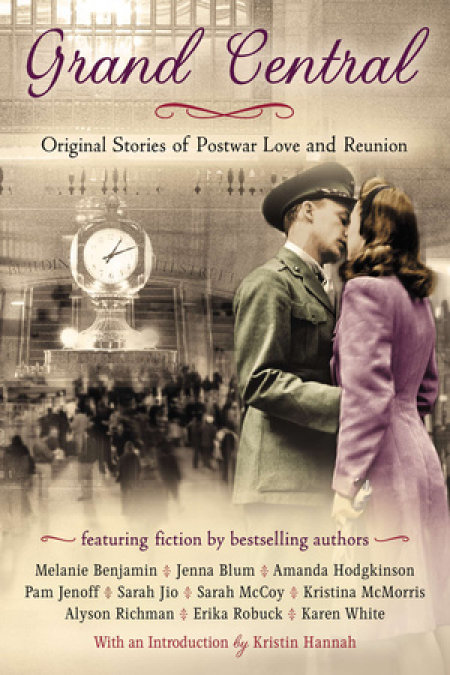

Grand Central

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A war bride awaits the arrival of her GI husband at the platform...

A Holocaust survivor works at the Oyster Bar, where a customer reminds him of his late mother...

A Hollywood hopeful anticipates her first screen test and a chance at stardom in the Kissing Room...

On any particular day, thousands upon thousands of people pass through New York City's Grand Central Terminal, through the whispering gallery, beneath the ceiling of stars, and past the information booth and its beckoning four-faced clock, to whatever destination is calling them. It is a place where people come to say hello and good-bye. And each person has a story to tell.

Now, ten bestselling authors inspired by this iconic landmark have created their own stories, set on the same day, just after the end of World War II, in a time of hope, uncertainty, change, and renewal.

Release date: July 1, 2014

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Grand Central

Karen White

I was born in sunny Southern California, in a time when the world was a simpler, quieter place. I rode my bicycle to the store and bought bottles of soda and Pop Rocks. My friends and I built forts in our manicured backyards and spent Sundays at the beach with our moms, wading in the water, splashing each other. The sun was always shining in my little corner of the world. Dads worked during the day and were rarely seen; moms couldn’t be ditched no matter how hard you tried. When the sun set, we all raced home on our bikes and gathered around a dinner table where there was almost always a hot casserole waiting.

I was a preteen when the Vietnam War changed the landscape around me. Suddenly there were protests and sit-ins and marches on the weekends; the police wore riot gear against college students. The nightly news was about body counts and bombs falling in faraway places. Then came Watergate. Nothing seemed safe or certain anymore.

I came of age reading about distant planets and unknown worlds. On my nightstand were novels by Tolkien and Heinlein and Bradbury and Herbert. I was a voracious reader, with my nose always buried in a book. I was constantly being admonished to quit reading and look up around me—especially on family vacations. In my high school years, it was Stephen King who held me in the palm of his hand and whispered to me that evil existed, but that it could be battled and beaten . . . if only one was strong enough, if only one truly believed. And I believed.

It wasn’t until later, when I grew up and got married and had a child of my own, that I began to see my life in context, to see how different the sixties and seventies and eighties were from the years that came before. I think that’s when I fell in love with World War II fiction.

World War II. Today, that’s all it takes for me. Tell me it’s a novel set during the war and you have a better than even chance of snagging my attention. Add that it’s epic or a love story and you have me ordering the book in advance.

There’s something inherently special about that war, at least as it is seen by the modern reader, which is to say, in retrospect. World War II was the last great war for Americans, the last time that good was good and evil was evil and there was no way to mistake the two. It was a time of national sacrifice and common goals. A time when we all agreed on what was important and what was worth fighting and dying for. Women wore white gloves and men wore hats. Through the prism of today’s contentious times, it seems almost impossibly romantic and polite. In our modern, divided and conflicted world, many of us long to glimpse a forgotten time, where the right path seemed easier to identify and follow. The “Greatest Generation.” That’s what we see when we look back now. It’s no wonder that stories about the men and women who lived and loved during that era seize our imagination and hold it so firmly.

World War II, like most wars, has been primarily defined by men. We learn in school about the battles and the skirmishes, about the bombs and the missions. We see the photographs of men marching on beaches and advancing up hillsides. We study the atrocities that were committed and remember the lives—indeed the generation—that was lost. But only recently have we begun to pay attention to the women.

In the World War II novel that I am currently writing, a female character says to her son, “We women were in the shadows of the war. There were no parades for us and few medals,” and I think that’s really true. In too much of our war fiction, women are forgotten, and yet the truth of their participation is fascinating and compelling and deserves to be at the forefront of the discussion about the aftermath of the war. Women were spies and pilots and code breakers. And of equal importance was their place on the home front. While the world was at war and the men were gone, it was the women who held life together, who gave the soldiers a safe place to return to. Many of the stories herein are focused on women and their lives on a single day in 1945, when the war was over but far from forgotten. Everyone had to readjust their lives after World War II—the men coming home, the women trying to return to a life that had been changed beyond recognition, the children who remembered nothing of peacetime. These are the themes and issues that continue to resonate with readers today.

I was enthralled by the short stories in this collection. This talented group of authors has taken an intriguing premise and coaxed from it a seamlessly integrated group of stories. In it, a single day in Grand Central Terminal—entrance to the melting pot of America—becomes the springboard for ten very different stories, which, when read together, weave a beautiful tapestry about men and women and their war years. In some, the characters are finding new lives after devastating losses; in others, the characters are battling the terrible effects of the war and trying to believe in a better future. In all of them, we see the changes wrought by World War II and the battles that often needed to be fought at home simply to survive and begin anew. And through all the stories is the melody of loss and renewal, the idea that something as simple as a song played on a violin in a train station can remind one of everything that was lost . . . and everything one hopes to regain.

Kristin Hannah

New York Times bestselling author of Home Front and Winter Garden

Going Home

ALYSON RICHMAN

He wasn’t sure whether it was the vaulted ceilings or the marble floors that created the building’s special acoustics. But on certain afternoons, when the pedestrian traffic was not too heavy, Gregori Yanovsky could close his eyes, place his chin on his violin, and convince himself that Grand Central Terminal was his very own Carnegie Hall.

Months before, he had discovered his perfect little corner of the terminal—the one just before the entrance to the subway, on the way to the Lexington Avenue exit. It was far enough from the thunder of the train tracks, yet still busy enough for foot traffic to yield him a few spare coins every couple of minutes.

He’d arrive early each morning from his apartment on Delancey Street and ascend the stairs of the subway with his shoulders back and his head held high. Something about carrying a violin case made him feel special amongst the throng of commuters. For concealed within his velvet-lined case was the possibility of magic, of music, of art, which no mere briefcase in the world could ever contain.

And although his suit jacket, with its thin grey flannel, was a far cry from the more stylish ones from Paul Stuart or Brooks Brothers worn by the men who arrived daily on trains from Larchmont or Greenwich, Gregori felt he transcended the shabbiness of his shirtsleeves. His elegance came instead from the simplicity and precision of his movements. The way he positioned his instrument against his collarbone. The graceful manner in which he lifted his bow. These were not flourishes that were taught in a finishing school or at suburban family meals.

He and his instrument needed each other, like partners in a waltz. Without the other, there could be no music.

As a child in Poland, Gregori had watched his father, Josek, soak his hands in milk every night to soften his calluses after a day of splitting wood. Josek had learned the craft of barrel making from his own father but secretly had always dreamed of making musical instruments instead. The barrels made him money and so kept food on the table and a roof over his family’s head, but music fed his soul.

On Friday nights, Josek invited anyone with an instrument into their home to fill it with music for his wife and child. Gregori still remembered his father twirling him around the room, as a neighbor played the balalaika. Years later, he would recall his father’s laughter. He could have tuned his violin on the sound of it. It was a perfect A.

During cart rides to the city of Krakow, with his father’s barrels loaded in the back and young Gregori sitting in the front, father and son would hum melodies together. Sometimes Josek would pull the cart over outside of a church, just to let his son listen to the organ music being played. Gregori seemed to come alive every time his father exposed him to melodies of any kind, whether it was the folk music of the village or the Mozart wafting out from one of the music schools in the city. Even more extraordinary was the boy’s remarkable ability to hum back any melody he heard, without missing a single note.

One night, when the rain was coming down so hard it sounded to Gregori as though the roof might collapse, there was a knock at the family’s door. When his mother opened the door, she found Josek’s friend Lev standing there under the doorway, with a man she did not recognize.

“We’ve been caught in the storm,” Lev said. “The wheel on my cart came off.”

He motioned to the man standing next to him, a hat pulled over his eyes. “I was trying to get my wife’s brother, Zelik, back to his home.”

Zelik raised one hand in greeting as he shuddered in the rain. In the other hand, Gregori’s father noticed a small dark case, shaped like a silhouette. Instinctively, he knew there had to be a violin inside.

“Come in before you ruin your instrument,” Josek said, waving the two men inside. His wife took their wet coats and hung them by the fire, while Josek and Gregori watched as Zelik placed his violin case on the table and unlatched it. Everyone gasped when they saw the glimmering instrument, which thankfully had not been damaged by the rain.

Gregori would never forget the sight of Zelik taking his violin out from his case, withdrawing the instrument as though he were a sorcerer. He still remembered that impending sense of magic as Zelik placed his chin on the edge, lifted his bow, and began to play. Zelik captivated everyone with the music that soon came forth in swirls and arabesques; the notes filled the room and thundered over the storm outside.

Zelik tapped his foot on the floor and bobbed his head from side to side. If joy had a sound, Gregori heard it that night from Zelik’s bow gliding over the strings. When the young man eventually put the instrument into Gregori’s hands, instructing him how to grasp the bow, all he could think about was learning to play it himself. The instrument had the capacity both to speak sorrow and to sing joy, all without a single word.

The next morning, after the sun reemerged and the wet timber and muddy roads began to dry, Zelik gave Gregori one last lesson. Gregori cradled the instrument in cupped hands. He slid his palm across the violin’s long, slim neck and fingered the tuning knobs. He felt as though he was touching beauty for the first time.

Zelik could see immediately how the boy’s hand naturally gripped the bow and could hear how he had a natural ear for melody. Zelik also sensed that, behind his closed eyes, Gregori didn’t just feel the music; instead it came forth from him as though he were breathing each note. As he grasped Josek’s hands, thanking him for giving him and Lev shelter that night, Zelik whispered into the man’s ear, “Your son has a gift. Sell what you must, but get him a violin and find a way to get him lessons. And do it as quickly as you can.”

Josek was able to get his son a violin in exchange for twelve pickle barrels made from his very best timber. After he saved enough money to feed his family, Josek used whatever funds remained to have a music teacher from a nearby village come to give Gregori lessons. The boy learned quickly how to play his scales, and then went on to more complicated études and sonatas that normally took other children far longer to master. Every so often, Josek would also take him into Krakow for a lesson and the opportunity to play with a piano accompanist. By the time he was ten, he could play all of the Mozart concertos. And when he was fifteen, he took his first stabs at the Mendelssohn.

But as much as he loved the music of the classical composers, after the weekly Shabbat dinners, Gregori always played the music of his shtetl. His fiddle work made his mother smile and his father pour the neighbors another glass of wine.

As he became older and his skills advanced, he started to dream of one day playing in Krakow’s prestigious Academy of Music and in candlelit recitals throughout Europe. But these dreams ended one night with the sound of breaking glass and his mother’s screams.

Before, the essence of his youth was a bowl of soup, a slice of bread, and his parents smiling to the sound of his violin. But that night, it was the sounds of terror and hate. Even fifteen years later, as he played in the safety and grandeur of Grand Central Terminal, the dark memories of his final days in his village often returned to him. The sight of his father being pulled from the house by an angry mob. The smell of burning barrels. The cries of his mother in the dark as the villagers torched their house, as his father lay bleeding and motionless on the ground. The word “Jew” slicing through the air like a scythe, uttered like a curse.

Gregori stood there watching, a voyeur to his own family’s destruction. All he wanted to do was rush over and kneel by his father, and remove the splinters of glass from his head, which looked like a broken gourd. He yearned to cradle his father in his arms and bring back the warmth that was flowing out of him, causing him to turn blue before Gregori’s eyes. But the boy’s limbs would simply not move. It was only when the family’s house was set ablaze that he felt his legs moving beneath him. They moved not by reason, but by instinct, his body lurching into the fire to save his violin.

—

Less than a year afterward, seventeen-year-old Gregori walked through Ellis Island. He had been sponsored by an older uncle whom his mother had not seen in years. In one hand, he carried a small leather suitcase, and in the other, he carried his violin. And beneath the material of his trousers were angry red patches of burn marks that wrapped around one leg. The scar looked like fire itself, a permanent red torch set in high relief against his skin. An eternal reminder of that horrible night.

His uncle had sponsored Gregori not purely out of compassion but also because he believed the boy’s music might draw customers to his restaurant on the Lower East Side. The first night, Gregori pulled out his violin in that crowded apartment on Delancey Street and serenaded his new family. The women let the dishes pile in the sink unwashed, their bodies instead anchored to their chairs as he played. As Gregori’s uncle scanned the room and saw the women transfixed, he was confident he’d have every table at his restaurant full by week’s end.

—

Nearly every night for three years, Gregori played countless mazurkas and tarantellas to diners enjoying their bowls of borscht and plates of stuffed cabbage. In some way, he enjoyed the warmth of the restaurant. The customers and their families reminded him of his Shabbat performances back in the shtetl. But it was hardly the type of playing Gregori had dreamed of when he was younger. As a new immigrant to a country that seemed so wealthy and full of prospects compared to Europe, Gregori wanted to find a way to harvest every opportunity. He didn’t just want to serenade men and women over his uncle’s pierogies and cabbage his entire life. He still carried the dream of playing on a stage alongside an orchestra, something that he had not yet had the chance to do.

So when he noticed an advertisement in one of the trade papers that a customer had left behind one night, indicating that the New Amsterdam Theater was holding auditions for musicians interested in their pit orchestra, Gregori took it as a sign. An opportunity waiting to be seized. He mustered up enough courage to go to the theater. There weren’t as many men there as he had expected, as such a great number of them were off serving in the war, a fate he had escaped because of the severe scarring on his legs. Still, there were so many talented musicians who came out to audition that when Gregori was offered a place as one of the second violins, it felt like a dream come true.

Even with his new job, Gregori still had his mornings and most early afternoons free. He chose to rehearse in the one place in New York he discovered he loved the most. Right in front of the entrance to Vanderbilt Hall, across from Murray’s pastry cart and Jack’s shoeshine booth. Grand Central Terminal, his own favorite stage.

—

The extra money he received from busking was nice, of course. Some days it barely covered the cost of his subway fare and lunch, but Gregori loved playing in Grand Central for many more reasons than the few dollars it added to his daily income: the acoustics, the vaulted ceiling with its turquoise plaster and gilded constellations, and the kinetic energy of the commuters. He found it thrilling that he was surrounded by so much motion, that he was in the epicenter of a thousand merging worlds. He could sense the rumble of the subway beneath his feet, and the wind from the train tunnels that blew in and out from the brass doors. Here, waitresses mingled with soldiers returning from the war, and bankers in chalk-striped suits sprinted next to the men who worked the elevators in their skyscraper offices lining Fifth Avenue.

There were also those few minutes each morning, when he leaned down to sprinkle the first few coins into the velvet of his case to encourage others to do the same, that he could hear the pattern of the foot traffic. It was a symphony to his ears. He could hear the gallop of a child’s patent leather shoes against the marble, the soft shuffle of a banker’s oxfords, or the drag of a wounded soldier’s crutch as it thumped against the floor. But one day he heard a patter of footsteps so unlike all the others he had heard over the years pounding against the marble that he felt a small twinge in his heart. The steps were light, almost airy, as if the heel of the shoe were barely touching the ground. Without even looking up, he could hear the spry, leaping sounds of a dancer.

—

He lifted his gaze and noticed a beautiful woman walking in his direction. She had just come up from the subway, her green silk dress fluttering like the ruffled edge of tulip leaves. Her face appeared to him in a flash: the pale skin, the dark hair, and foxlike eyes that looked almost like they belonged to another place. Not a typical American, in the way he thought of Americans, though he knew every person here could claim ancestry from abroad. But in Gregori’s mind, the American face belonged to those of English or Irish descent, with their small-carved features and peaches-and-cream skin. This girl instead had the high cheekbones and coloring that reminded him of the girls back in his village. But really she could have been from any country in Central or Eastern Europe, he thought. Hungarian or Lithuanian. Polish or Russian, maybe. Or even Czech.

Her footsteps had slowed, and now she stood only a few feet from him. She had stopped in front of the pastry cart that sold glazed doughnuts for a nickel and apple strudel for a dime. Around her pooled a dozen other commuters eager for something sweet before their morning’s work consumed them.

Her long legs and shapely back were evident through the silk of her dress. She wore her black hair in soft curls around her face, just like the starlets in the movies. But her movements were somehow old-fashioned and slightly tentative, the way a person who wasn’t born in America might search for the right coins in her purse, or how someone new to Manhattan might pull slightly away when someone’s sleeve brushed against their own. He noticed a difference in the way she moved when there was no one around, compared to the way she moved when she was thrust into a group. The ease was replaced with caution. As if beneath the carefree veneer there was something more complex, something she kept hidden behind a radiant facade. This did not deter Gregori. On the contrary, it increased his fascination. The contrast was like music itself. On the surface, an untrained ear would hear only beauty when he played something like Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor. Only a few would also hear the sadness that floated from the strings. Two contradictory emotions, braided like rope, the true essence of a human soul.

—

Gregori quickly pondered the best way to gain her attention. He had yet to begin his playing that morning, and as he stood holding his violin in his hands, his mind now raced as to what music to select. He desperately wanted to find a way to reach her, to make her stop—if only for a moment—and take notice of the music intended just for her.

It quickly occurred to him that if he could find something that reminded her of her homeland, it might be enough to make her pause and linger just a bit.

But time was ticking away as he watched her pay for what looked like a small piece of strudel now safely tucked inside a wax paper bag.

His heart was racing. He knew that Mozart had never failed him with the crowds, so he began playing Eine kleine Nachtmusik. It was popular enough that even if she weren’t from Austria, she still might recognize the melody and walk over to him. Then, once he had finished, he could ask her where she was from and their conversation would come naturally, just like a dance.

He played with half-closed eyelids, not wanting to remove his gaze from her for even a moment. As his bow moved across the strings, his body bouncing to the music, he saw her dip her fingers into the wax paper bag and pull out her pastry. But even though the melody got livelier, she barely seemed to take notice of him.

Gregori watched, crestfallen, as she headed toward the Lexington Avenue exit, her hips moving beneath her dress as she pushed through the heavy, brass-edged doors.

—

As Liesel crossed over Lexington, past the Bowery Savings Bank branch and the newspaper stand, she kept her stride brisk and glided by any older pedestrians who would have slowed her down. One thing she prided herself on was her punctuality. She didn’t like to keep Mr. Stein waiting. If he requested she arrive by one thirty P.M., she’d be at his building a few minutes before. Just enough time to fluff out her hair and smooth down her dress.

Nor did she want to arrive at his office with bits of apple strudel on her lips. So she quickly finished her pastry and, on the corner of 46th Street and Lexington Avenue, took out a napkin and blotted her lips to make sure there were no crumbs. She took a compact out of her purse and swept a dusting of powder over her face. Then, as she had watched the other dancers do a thousand times, she reapplied her lipstick before taking one final look in the compact mirror and snapping it shut.

Liesel was happy that Leo Stein’s office was on Lexington Avenue, not on Broadway like most of the other theatrical agents. This meant that she had to take the 42nd Street shuttle from her sewing job near the theater district to get to him. But it was a route she loved because it enabled her to pass the only pastry kiosk in all of New York that had apple strudel exactly like her mother used to make. If she had an extra few minutes, she’d walk toward the central concourse and enjoy the pastry under the gilded images of the zodiac, those finely painted constellations resplendent in a sea of blue.

Liesel loved the very vastness of the rotunda, with its cathedral-like opulence, and the way the light streamed through the east entrance’s arched windows and illuminated the commuters in a sepia-soft glow. It was a place where she could feel both alone and safe amongst the crowd. And even more poignantly, it was where she could imagine a chance meeting or a potential reunion with the family she still refused to accept as lost.

—

It was hard to believe it had been over five years since she had seen her family and that there had been no contact with them since the last letter arrived.

“The time will go quickly,” her mother had promised her as she packed for America.

What her mother had told her was true. Time had gone by quicker than she’d imagined, but it wasn’t without a lot of work on her part. Liesel had done everything she could to keep herself as busy as possible. She didn’t want to have time to think, because during those pauses, it was hard not to imagine what terror had befallen her family.

What she also loved about Grand Central Terminal was that everyone there was off to another place and they all had a sense of urgency to their journey. This was compounded by the fact that there were clocks everywhere: brass-rimmed clocks fastened onto the marble walls, the famed one in the center of the concourse, and downstairs by the tracks, there were clocks suspended from the ceiling. Some had art nouveau embellishments, and others looked like larger versions of watch faces. But no matter the style, the clocks all gave a sense that one had to keep moving, and Liesel liked this. It enabled her to focus on her responsibilities. When she wasn’t dancing, she was sewing. And when she wasn’t sewing, she was dancing, either at her ballet studies or performing at the supper clubs that helped pay her bills.

She had never imagined that she’d be able to make enough money dancing to support herself, but Leo Stein had changed all that for her. She would always be grateful he had taken her on as one of his girls. His agency was on the third floor of a slim grey brownstone that had been converted into small offices. Upon arriving, she buzzed the doorbell and climbed up the narrow stairs. She could smell his cigar smoke from the first landing.

Leo Stein, Talent Agent was carved on the dark wooden door. She entered without knocking.

“Hello, my sheyna meydel,” he called out to her. “What a sight for sore eyes.”

She sat down across from his desk, folding her hands in the green silk folds of the dress that she had made herself the week before.

“So, today through Friday afternoon it’s rehearsal on this side of town, at Rosenthal’s studio. Not over on Broadway for a change . . .”

She nodded. She appreciated how he treated her with kindness, never overtaxed her, but would instead take her other obligations into account when assigning her work. So he arranged for her to work in the supper clubs on Friday through Sunday, meaning that aside from the rehearsals to learn that weekend’s choreography, she was still free to do everything else: the sewing for her boss, Gerta, and the ballet training she refused to give up, even though it provided her with no income yet. It just meant she was busy all the time, which was exactly what Liesel wanted.

Leo handed her a rehearsal schedule. “Check back with me later this week on your way to Rosenthal’s. I think I might have something at the Crown Club for next week, but it’s not confirmed yet.”

She smiled. “Well, you know I’ll be ready when you need me, Mr. Stein.”

Leo reached into the desk drawer. “You never stop, do you? One of the hardest-working girls I know. To think, if you wanted to do this full-time, how much of a commission I could make off of you!”

“I don’t want to break my promise to Gerta.” She smiled and fluttered her eyelids, not to be coy, but because she enjoyed being especially sweet to him. “And I can’t disappoint my teacher, Psota, either.”

Leo nodded. He knew very well that her teacher, Ivan Psota, was the one who had gotten her out of Czechoslovakia in time.

“Yes, yes. I know how much you owe him. That’s why I don’t push you like I do the other girls.”

“I’m very grateful, Mr. Stein.”

“Just be thankful that you look like my daughter.” He shook his head, placed his cigar on the ashtray, and reached for his desk drawer.

“I’ve taken out my commission, but the rest is for you, sweetheart.”

She glanced quickly at the hand-drawn numbers and Leo’s rolling signature on the bottom. Twenty-five dollars. Enough to pay her room and board, as well as some to put away in case the Red Cross was ever able to locate her family and she could bring them over.

Leo glanced at his watch. “So, Rosenthal’s studio. It’s on 38th and Lex. Better get going. You need to be there by two.”

Liesel had twenty minutes.

“Thank you, Mr. Stein.” She said the words carefully and respectfully, ensuring, once again, that he could hear the gratitude in her voice.

—

Liesel knew she had many things in her life to be grateful for. And one of the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...