The End

Mother’s Day

People say there’s nothing like a mother’s love. Take that away, you’ll find there’s nothing like a daughter’s hate. I told myself things would be different when I became a mum. I was determined not to make the same mistakes as my mother, and I believed that my child would always be loved. That’s what I promised my daughter the day she was born.

But I have. Made mistakes. Bad ones.

And I have broken my promise more than once.

I feel drunk from tiredness. My mind is a mess and my thoughts feel slow, jumbled, clouded by the fog of exhaustion. But she needs things and she needs me to get them for her. Doing, finding, being what she needs became my occupation the day she was born. A job I thought I wanted and now can’t quit. Being a mother is a curious mix of love, hate, and guilt. I worry I am the only person who has ever felt this way, and despise myself for thinking unthinkable thoughts.

I wish my daughter would disappear.

I push the buggy along the high street, hoping to get inside the supermarket before the rain comes, when an elderly woman blocks my path.

“Isn’t she adorable,” she says, staring at the sleeping child before beaming back at me.

I hesitate, searching my befuddled brain for the correct response. “Yes.”

“How old?”

“Six months.”

“She’s beautiful.”

She’s a nightmare.

“Thank you,” I say. I tell my face to smile but it doesn’t listen.

Please don’t wake her.

That is all I ever think. Because if someone or something wakes her she will start to cry again. And if she cries again, I will cry again. Or do something worse.

Inside the supermarket I hurry to get the things I need: baby formula, nappies, coffee. Then I see a familiar face—an old colleague—and for a moment I forget how tired I am all day, every day. I listen to the childless friend who has become a stranger talk about their life, which sounds significantly more interesting than mine. I live alone and I miss having conversations with adults. We chat for a while. I mostly listen, as I don’t have much to say—every day is exactly the same as the day before for me now. And while I listen, I forget that I no longer have any dreams or ambitions or a life of my own. My daughter became my world, my purpose, my everything the day she was born.

I sometimes wish she hadn’t been.

I know I must never share these thoughts or speak them out loud. Instead I pretend to be okay, pretend to be happy, pretend to know what I am doing. I’m good at pretending but it is exhausting. Like everything else in my life. Like her.

The conversation lasts less than three minutes.

My back is turned less than two.

One minute later my world ends.

The buggy is empty.

Time stops. The supermarket is suddenly silent, as though someone has turned down the volume. Muted a life that was always too loud. I never thought I would wish to hear her crying, long to see that tiny scrunched-up face, endlessly screaming and red with inexplicable rage. The only sound now is the thud of my heartbeat in my ears, and I feel wide-awake for the first time in days.

I stare at the empty stroller, wondering if I left the baby at home. I was so tired yesterday I put my phone in the fridge by accident. Maybe I forgot to put the baby in the buggy before I left the house today? But then I remember the elderly woman on the street, she saw the baby. The friend who is now a stranger saw the baby too. I saw the baby, five minutes ago. Maybe ten. When did I last see her? The panic rises and I spin around, looking up and down the supermarket aisle. She’s gone. The baby is too young to crawl. She didn’t climb out by herself.

Someone has taken her.

The words whisper themselves inside my head. I feel sick and I start to cry.

I look up and down the aisle again. The other shoppers are going about their business, behaving as though nothing has happened. It’s been seconds since I noticed she was gone but it feels like minutes. Am I dreaming? I’ve had this nightmare before. I sometimes wished she wasn’t born but I didn’t mean it. I never meant it. I love her more than I knew it was possible to love.

I’m shaking and I’m crying and my tears blur my vision.

I wished my daughter would disappear and now someone has taken the baby.

I whisper her name.

Then I scream it.

People stop and stare. I feel as though I can’t breathe.

Life is suddenly loud again. I start to run, desperately looking for any sign of the child or the person who has taken her. I see a woman carrying a baby and I feel rage, then relief, then humiliation when I realize it isn’t her. I apologize and keep running, keep searching, keep screaming her name even though she is too little to know how to answer. People are staring at me and I don’t care. I have to find her, I need her, I love her. She is mine and I am hers. I would do anything for her. I will never think bad thoughts about her again.

But she is gone.

My chest hurts as though my heart is actually breaking.

And I am crying. And I am falling to the floor. And people are trying to help me.

But nobody can help me.

The child, my world, my everything has been taken.

I wished my daughter would disappear and now the baby is gone.

I already fear I will never see her again and it is all my fault.

Because I know who has stolen her.

And I know why.

Frankie

Another Mother’s Day

She was her mother’s daughter. People often said that, and Frankie agrees as she stares at the framed photo of her little girl who has been gone too long. They share the same green eyes, same smile, same wild curly hair. She slips the silver frame into her bag and takes one last look around the prison library. Today is her final day as head librarian at HMP Crossroads, not that anyone else knows that. Yet.

Mother’s Day has never been easy, and nothing Frankie does to distract herself from her grief works anymore. There is no greater pain than losing a child and it’s hard to forget someone you so badly want to remember. Her daughter was a teenager when she disappeared, but that doesn’t make it any easier than losing a younger child. And it doesn’t help that she can’t tell anyone what really happened, not that talking about it would bring her daughter back. Better to keep busy. Hard work has always been the best cure for heartbreak.

She switches off the outdated computer and picks up her mug. It was a gift a few years ago—handmade and hand-painted—with a wonky handle and Frankie’s name on the front. Her other name. The one that is redundant now. Mum. It’s the only mug she likes to drink from, at work and at home, so she takes it everywhere. She never leaves it here. Frankie doesn’t like other people touching her special things. She walks the fourteen steps from her desk to the library door, then turns off the lights and stands in the darkness for a moment, no longer trusting herself or her senses. Her tired eyes sometimes see shapes inside shadows these days, things that her mind insists aren’t really there. So she turns the lights back on, listens to the hum of silence, and waits for her breathing to slow down.

Frankie wasn’t always afraid of the dark.

She turns the lights on and off three times, but everything is the same as before. The same as it always was. People spend too long adjusting to the light instead of the dark, it’s why they are so unprepared when bad things happen to them. Frankie counts down from ten before locking the library door for the last time. She has thirteen keys attached to the belt of her uniform to choose from, but can select the correct key for every lock without looking. The cut and shape and feel of the cool metal in her hands bring comfort. She likes to push individual keys into the tips of her fingers until they hurt and leave a mark. Feeling something—even pain—is better than feeling nothing at all.

There are twenty-two steps from the prison library to the stairs. She likes to count them. Silently, of course. Counting things has always helped Frankie to keep calm. She reaches another door, finds another key, then steps through into the stairwell before locking the previous door behind her.

There are forty steps down, then five to the outside door.

The big key this time.

Fifty-eight steps across the courtyard, sticking to the path, avoiding the grass.

The big key again.

Eighteen steps to reception. Twelve to her locker, where she retrieves her phone and sharp objects. It took Frankie a while to get used to being searched on her way into work, and having to leave her personal belongings behind each day. But she learned to adapt. She knows that doesn’t make her special; the ability to cope with change is as essential as water or air. The same rules apply to all things and all people. Everything in life that is now normal was once unfamiliar.

She checks her phone but there are no new messages or missed calls. She sets an alarm to remind herself to set another alarm later. Frankie likes setting alarms on her phone for everything, it’s the only time it makes a sound. There are thirty-two steps to the outside gate. She always walks more quickly for this part of the journey but does not know why. Fast, determined steps, as though she is trying to outpace herself. Or run away. She whispers the number of steps left like a numerical mantra. Or a prayer.

Thirty-two. Thirty-one. Thirty. Twenty-nine.

It’s as though all the numbers in her head need to find a way out of her. Buzzing like bees until they escape her lips and fly away.

Nineteen. Eighteen. Seventeen. Sixteen.

Frankie knows the guard at the final checkpoint well enough to say hello. He’s asked her to go for a drink with him, twice. Frankie said no. She prefers to drink alone and people cannot be trusted. Not trusting people was her mother’s number one rule and it is one she inherited. Frankie doesn’t know why men find her attractive, maybe it’s her prison uniform. A uniform that is nothing more than a stereotype, a fantasy, a disguise. We all play daily dress-up games, choosing which character to be when selecting something from our wardrobe. Deciding who we want others to see us as, hiding behind our clothes. The world is full of people who are good at being bad, and people who are bad at being good. She has always thought of herself as a good bad girl. Someone who made the best of the bad life she was born into, and tried to do something good with it. But when Frankie looks in the mirror these days, all she sees is a plain-looking woman in her thirties. A woman with dark circles beneath her eyes and a mess of dark curls that have always refused to be tamed. A woman who resembles someone she used to know.

A ghost.

The guard steps out of the little security hut that borders the inside and outside. He smiles and she feels herself shrink. His name badge says Tom but he looks like a Tim.

Thirteen steps. Or was that twelve?

Everyone calls it a hut, but it’s made of thick reinforced concrete walls, with barbed wire on the roof, and it is staffed with armed guards 24–7. Tom is a little older than Frankie. He’s tall, but his broad shoulders are always a little hunched, as though he is embarrassed by his own height.

Ten steps. Nine.

Frankie stares down at her feet to avoid his gaze—she does not like people looking at her—and notices that her shoelace has come untied. It can wait; there is no time to stop.

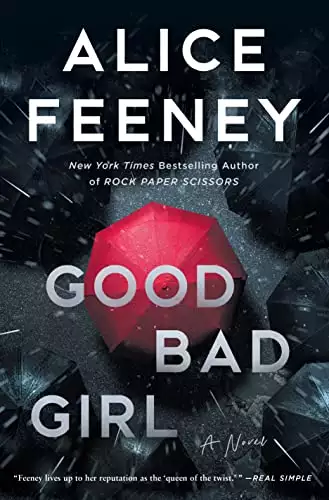

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved