One

It started at dawn the way long days do when they run straight on from very long nights. Ada was on a streak of long nights and her days were relatively brief, starting in the afternoon and vanishing by lunch which was, in fact, dinner, but meals didn’t matter because she was twenty-six. Regimented mealtimes are for toddlers and families and the very, very old and to try to force an 8 p.m. curfew on the appetite of a twenty-six-year-old is to misunderstand the beast.

So the days were short but this dawn was in August, in Edinburgh, where the nights are lit like afternoons. When Ada first moved to London, it was summer and she was amazed by the flexible, bright evenings, eating dinner outside during European hours. She didn’t know then that the stretching light was to compensate for the months she’d be plunged into darkness. She called her parents in Sydney the following January and told them seriously that she was concerned the winter was permanent.

‘We’re eighteen days into this year and the sun hasn’t come out yet,’ and when they countered gently that that’s simply how seasons work, spring will come, it’ll come, she nodded like she believed them but actually she wasn’t sure. She’d never lived through winter like this. Sydney winter was London spring, composed of brisk baby days. Spring did come wetly in eventually but by then Ada knew not to trust it.

Next summer she spent desperately, suspiciously, outside, waiting for the drop.

And this was the summer after that.

It started at dawn and Ada was perched on the corner of a sofa at the party after the party after the closing night gig of the Edinburgh Fringe. Ada was at the end of a season of a particularly worthy play about London knife crime, written by a drama school student who grew up in the Cotswolds. It was a bad play, Ada knew, but the director came from money of some kind and was willing to blow that money on Equity rates. Ada hadn’t auditioned but had been recommended by her friend Ben, who was already in the cast because he’d gone to the director’s drama school and that was how Fringe theatre worked. Without those connections to fall back on, Ada relied on referrals. So she gave it her all in her three scenes playing the teacher everyone trusted, doling out advice to teenagers played by people her age. And then at night she did whatever she wanted.

She was talking to a friend of a friend – the kind of person who’s always at the parties after the parties but never at the parties themselves – though she realised this friend of a friend hadn’t been at any parties all month, not with her anyway, so maybe this was special. They were sharing a bottle of supermarket-branded bourbon, one of a selection Ada usually kept in her room but, as the month had dragged on and her pounds had drained out, moved into her handbag.

People found it charming, her carrying around a bottle of cheap bourbon, and she was aware that if she were a man or old or if she laughed a little less confidently or if she didn’t sleep with so many people, then? It would be worrying, this bourbon-bottle-in-the-bag situation. But she didn’t plan to stop laughing or fucking any time soon and age was a threat that was hard to take seriously at 5 a.m. It was particularly hard to take seriously as Sadie, the friend of a friend (of many friends actually, none of them close) shifted closer to her and nudged her so she toppled from the arm of the couch onto her lap.

‘That’s better,’ Ada said and touched Sadie’s face and Sadie shrugged and looked away. Sadie was wearing a plain white singlet and dark skinny jeans, an outfit that would barely contain Ada’s body but sat neatly over Sadie’s. Ada wanted to ask her about her name because Sadie was Australian and no Australians were called Sadie. There was this famous song from the seventies about a cleaning lady called Sadie and since then everyone avoided the name so she said, ‘Sadie, what’s with—?’ but Sadie was already talking to the person on the other side of her.

The party had divided into a grown-ups and kids table vibe, with Ada’s friends firmly at the kids table, which was covered in baggies and squashed-up cigarette papers with gum inside. Sadie was talking to Confirmed Adults, the actors who got reviewed by The Times and the comedians who were regulars on Mock the Week and didn’t cheat on their wives. Ada knew that Sadie was a playwright – because every Australian at the Fringe was vaguely aware of every other – and the people in this circle wanted to talk to her so she was probably pretty good. But when Ada leaned in to join the conversation Sadie made space for her, slightly squeezing out the older woman with the RADA accent who had opinions on Sadie’s career and no opinions at all on Ada’s.

Sadie liked her enough, Ada decided, for this morning only and the morning would end soon. Chatting about a song would waste their time so she tapped Sadie’s arm and, when that didn’t work, pulled on her ear so she had her attention. Ada said, ‘Can I take you home now?’ and Sadie said, ‘You don’t want to stay longer?’ and Ada said, ‘It’s morning’ and Sadie said, ‘OK. I’ll get our coats.’

It was weird to hear an Australian say, ‘I’ll get our coats,’ Ada thought but didn’t say because she didn’t want their only connection to be their foreignness. Watching TV as a child lying backwards on her parents’ couch under a spinning fan and the mom on screen is saying, ‘Get your coat, we’re leaving!’ or the nanny whispers, ‘Children, get your coats,’ or the man leans in to the woman and says, ‘Should I get our coats?’ No one ever told Ada to get her coat in her whole sunny childhood because she simply didn’t own one and the ritual collection of coats as a means of exit was a northern hemisphere fantasy. Now Ada had three coats, none of them good.

Sadie was getting one of those bad coats when Bernie touched Ada’s arm. Bernie was probably thirty-five in human years but had an eternal carnie spirit, always at a festival, the host of the party though this wasn’t his flat. He had also hosted the mixed bill show that Ada had performed on that night, where she sang a passable version of ‘Nothing’ from A Chorus Line for drink tickets, a holdover from her musical theatre phase. Bernie liked her in the neutral sort of way men in their thirties liked her, because she was rude to them and conciliatory (and discreet) to any age-appropriate wives or girlfriends who would show up along the way.

‘You’re not leaving!’ Bernie said and then without pause, ‘Something for the road?’ and he opened the bathroom door and Ada followed him in. She said, ‘You should be leaving too, old man,’ and he laughed – thirty-five-year-old men loved to be called old though it had less of a hit rate when they were forty-five – and he said, ‘Ah, you’re probably right. But tomorrow we go back to real life!’ as he racked up four thick lines. Ada bent over the unsteady board he was holding – did he take this from the kitchen or did whoever owned the flat keep chopping boards in the loo? – and inhaled once, twice, then paused to watch Bernie take one

of his own.

Sadie knocked on the door and asked if she was ready to go. Ada offered Sadie the final line – ‘Hey!’ said Bernie and Ada laughed and said ‘No more for you, pops’ – and Sadie leaned over and inhaled. After she stood up, she took Ada’s hand and the board hit the floor and they sprinted through the flat, opening the heavy door with three locks, and down the stone stairwell into the grey entranceway with bikes and fliers with bike tracks on them all over the floor.

They made their way out onto the doorstep and Ada turned to Sadie and pinned her lightly, watching her face in the pink and grey. They shivered and Ada was briefly annoyed because yes it’s dawn but shouldn’t it be warmer than this? Then she kissed Sadie and tasted coke in her mouth. She pulled away and said, ‘I had to make sure we had chemistry before you came home with me, wouldn’t that be embarrassing?’ and Sadie smiled and closed her eyes and said, ‘Yeah we’d never have recovered.’ Ada wanted her to open her eyes so she dragged her off the wall by the wrist. They passed crowds of university students, spending their holidays doing experimental dance pieces for audiences of eight and fucking for the first time and that was Ada recently but she felt contempt anyway.

Why would you be twenty-one when you could be twenty-six? Why would you be thirty-one? Ada’s contempt was usually gentle, sometimes closer to pity, but not now in the early hours as she pulled a woman steadily closer to her room. She had never wanted to be any age other than this one and she was going to be this age for as long as she was allowed.

They entered the building with Ada’s flat in it and it looked exactly the same as the building they’d just left. Every building in Edinburgh looked exactly the same to Ada, except the castle and the various Fringe venues that looked like they were also castles but were in fact part of the university. Ada had spent all night in a science building recently, watching immersive theatre about ancient Greece and being distracted by the Bunsen burners in storage cupboards behind her head. The actors were probably pretty good but then Ada thought everything was good at 1 a.m. and better at 2 and the guy playing Helios was hot which was probably the point. She wondered if he was in on the joke.

All four of Ada’s flatmates were asleep. She whispered to Sadie that she was living with some actors from her show who were ‘too serious about their craft to party’ and Sadie said, ‘Orson Welles would be horrified,’ and Ada said, ‘Very current reference.’ Sadie said, ‘Sorry, I’ve been staying with my producer who is literally fifty,’ and Ada put her finger to her lips. They crept through the creaking living room with leather chairs that were somehow too hot to sit in even here and they went into her room.

This room, like all the rooms in the flat, usually housed a university student, and when Ada had arrived at the start of the month it was empty but for a bed and a desk and a melted stub of a candle stuck to the mantlepiece. Students fled Edinburgh in August to go back

to their families and the friends from home whose news they were mostly indifferent to, and Ada felt contempt for that too. August was the only time she wanted to be in Edinburgh, when people like her climbed into the nooks left behind by the students, smeared make-up on their sheets and covered their old musty buildings with posters. She was aware that this wasn’t how she was supposed to feel – it was disrespectful to the locals and to history, probably, to care so little about the city that was home for one twelfth of her year – but she found the place frictionless without the Fringe. She’d been a plus-one to a wedding in Edinburgh in February and it was so quiet and cold and no one in the streets smiled at her when she passed them and she wondered what the point was. There was a beach just outside town that no one even used and that was all she needed to know about that.

Ada and Sadie undressed by the window, each removing their own clothes, Ada staring hard at Sadie and Sadie with her eyes closed, again, closed to Ada, smiling. Ada didn’t like that at all and she said, ‘Open your eyes, my god,’ and Sadie did, looking surprised, then kissed Ada with her teeth a little bared and pushed her over to the bed. Sadie came and kneeled over her. Ada knew that Sadie thought she had to take over now – hard-edged women like Sadie expected certain things of girls like Ada and those things were ‘very little’ – and Ada loved to surprise them. Because Ada was exactly herself when she was naked with someone. Some people are more themselves, some people retreat but Ada was exactly the same and it unsettled her partners.

Ada pulled Sadie down and climbed on top of her and Sadie raised an eyebrow then closed her eyes again and said ‘All right, Ada,’ and just saying her name almost made up for the closed eyes. Ada bent to her neck and grazed it with her teeth while running her nails down the space between Sadie’s breasts. Sadie’s skin was dark and Ada wondered briefly why her nipples hadn’t been visible through her white top. She felt Sadie ease towards her and smiled then sat up. And saw blood. Blood smeared on Sadie’s cheek and neck and on the blue and brown striped sheets that had come with the flat – ‘I’m like a boy of fourteen again,’ she’d said to her flatmate Ben the first time she put those sheets on and he said, ‘What do you mean?’ and she hadn’t bothered explaining. She touched her nose and when she pulled her hand away, blood, right from the source.

She sat back on Sadie and said, ‘Sadie, I need to tell you something,’ because she was still lying there with her eyes closed and that would normally have upset Ada but it was pretty funny under the circumstances. Sadie smiled and said, ‘Tell me anything,’ and Ada started to laugh, right from her belly, which made her rock forward on Sadie in a way that they both liked until Sadie finally, finally looked at her and saw her covered in blood, her

long dark hair dragging in it, and Sadie drew her legs in and backed up the bed. Ada kept laughing but gestured to her nose and said, ‘It’s this, it’s just this,’ and Sadie gradually understood and she laughed too, though she looked uneasy, possibly revolted, and Ada thought, Good.

Ada stood up eventually, grabbed her make-up wipes from the desk and threw them at Sadie. ‘Clean yourself up girl, you’re a mess.’

Sadie laughed again, a little more assuredly this time as Ada tipped her head back to stop the bleeding. It stuck in her throat, mingling with the leftover chemical taste and she felt powerful. Once it stopped running, she opened a water bottle over her head and it drained off her onto the floorboards and she was vaguely aware that she needed to move out of this room in twelve hours but instead of drying the floor, she dabbed herself with a towel, turning it streaky and pink. She turned back to Sadie, who was watching her, and who said in a flat voice, ‘The black-widow look is good on you,’ so Ada dropped the towel and crawled towards her, climbed up the bed and wrapped her many legs around this woman who could take or leave her an hour ago. She licked her fingers and Sadie shuddered but she just used them to scrub the blood from Sadie’s left ear.

‘This is our Paris, you know,’ she said conversationally as Sadie tightened her grip on her hips.

‘What does that mean?’

‘You know, the line, “We’ll always have Paris”? Well we’ll always have . . . this.’

Sadie shook her head and said, ‘You’re disgusting,’ and later Ada sang ‘Incy Wincy Spider’ as she moved down Sadie’s body and it should have been embarrassing but it wasn’t at all.

And then they lay apart, Sadie on her side facing Ada who stared at the high, sculpted ceiling, the bare bulb hanging from a wire that would swing threateningly if this were a horror movie but was now obedient and still. Ada wondered if that made this a romance instead of a horror movie or maybe it was a horror movie and she was the murderer. After all, she’d covered them both in blood. But it was a peculiar sort of feminism that meant that a woman who looked like her would never be the killer. She wasn’t an icy Gillian Flynn blonde or a dark-eyed femme fatale. Women who kill weren’t round-cheeked and hard around the calves but soft at the biceps. They didn’t freckle as easily as they smiled.

Ada thought of her face as one that no one could hold in their head for long. Sometimes she caught herself in a bus window and saw herself drained of expression and she was anonymous. She knew that guardedness and reserve are attractive qualities in a woman, she was attracted to them herself, but other women’s physical features contained more value on their own than hers. Ada let every thought she had play across her face and that was both her instinct and also by design. If she couldn’t draw people to her using an air of mystery she’d do it by being so open they thought she must be lying.

Ada rolled towards Sadie who turned quickly onto her back so they weren’t facing each other. This annoyed Ada and so she said, ‘That’s annoying, why are you always turning away from me?’ and Sadie said,

‘Sorry, sorry, I’m just really high,’ and she did sound sorry but she didn’t sound that high. Ada lay her palm flat on Sadie’s ribs and felt a whole world moving underneath and said, ‘You don’t seem high. You’re so calm. You seem exactly the same as you did at the party,’ and she knew there was doubt coating her words and she hoped that Sadie would turn to her and deny it, say everything had changed, she’d never been so dragged out by a woman, she couldn’t look at her because she was afraid of what she’d feel! But instead, Sadie sighed and closed her eyes and said, ‘Sorry I’m not manic enough or whatever.’ Ada felt like she was being separated from her friends in class for talking too much.

Ada said, ‘You did, like, one line though,’ and even as she said it she wanted to leave it alone. Sadie laughed and started rubbing her feet together and said, ‘I don’t do coke much, you know how expensive it is back home.’ Ada reached out and rubbed her hand over the side of Sadie’s fuzzy, growing-out undercut and said, ‘Well yeah, but that’s the thing about coke, you don’t buy it, it’s just always around. Hey, did you hear that Bernie’s girlfriend is pregnant? He asked me if I think he’ll be a good dad.’

Sadie shifted her head slightly, enough for Ada to know to withdraw, and said, ‘Men don’t offer me coke, Ada. So unless they offer it to a woman who offers it to me . . .’

Ada laughed. ‘Wow, I never knew femmeness was so key to drug muling, do gender studies professors know about this?’ But Sadie was quiet so she couldn’t tell if she found it funny. Ada felt tired of performing for her but that didn’t mean she was ready to stop. She considered telling her that, actually, she did think Bernie might be a good dad, that she’d told him he should call the baby Ada and he’d smiled affectionately and kissed her head. But she didn’t think Sadie liked Bernie much.

Sadie got up to use the bathroom, getting fully dressed to do so, making Ada anxious she wouldn’t come back. But she did and as she undressed again – grateful, Ada felt so grateful – she looked at the little bowl on Ada’s desk.

‘Blackberries?’ she asked and Ada sat up in bed.

‘They call them brambles here and you can forage them, like just take them from the bushes. I got these near Arthur’s Seat, the big . . . rock thing.’

Sadie said, ‘Yes, I’m aware of the big rock thing, I’ve done the dawn climb a few times,’ and Ada said, ‘You went UP it? OK, Tank Girl. Well, I brought them back to ripen so I could make a crumble but I guess I’m out of time.’ Sadie picked up a little handful and brought them to bed, held out her palm and Ada ate some, directly off it, and her throat tingled as they slipped down. Sadie dropped the rest into her own mouth, swallowed and said, ‘Yeah, they’re not ripe at all.’ And she lay down and closed her eyes.

They were silent again,

for longer this time, long enough for the light through the window to warm up and one of Ada’s flatmates to turn on the shower in the next room. Sadie slept and Ada drifted but she didn’t want to lose time so she kept pressing her palms over her eyes to see the fireworks, or that might have been a dream. Another flatmate turned the coffee maker on and the noise was enough to pull Sadie a little way back to her so Ada took her chance and climbed up onto her knees. She leaned over and put her face as close as she could to Sadie’s until Sadie said, ‘What?’ and Ada said, ‘If you’re way older than you look, you have to tell me.’

Sadie opened her eyes and she was dead on with Ada but blurred at the edges.

‘Why,’ asked Sadie, ‘would I be older than I look?’

Ada started to sing, into Sadie’s face, louder than she needed, ‘Oh scrub your floors, do your chores, dear old Sadie,’ and Sadie pushed her away. Ada was off balance and fell onto her back, the mattress creaking beneath her and Sadie sat up and shook it off.

‘I should never hook up with other Australians.’

Ada laughed and said, ‘So either your parents are massive Johnny Farnham fans or you were born before that song came out so you’re like sixty. Nice tits for an old cleaning lady, I have to say.’

Sadie glanced over at Ada and said flatly, ‘There’s still blood on your throat,’ and Ada started to sing again.

‘Sadie, the cleaning lady, will clean the blood off me . . . uh . . . Sadie,’ and Sadie climbed on top of her and clamped her hand over her mouth. She was still looking slightly over Ada’s head, smiling at whatever phantom floated there and without lowering her eyes to Ada’s she said, ‘I think I’m sobered up now.’

Ada lay perfectly still because she knew if she moved it would be obvious how desperate she was for this morning to continue. Once Sadie was out in the world she’d be gone, this would be gone; this room wouldn’t be hers by 4 p.m. and nothing that had happened here made her believe that there’d be another room for them. Their Paris. Had she said that out loud?

Sadie slowly removed her hand from Ada’s mouth and said, ‘I think I know what your problem is,’ and Ada said, ‘Is it that I know the words to a John Farnham song? Sorry for being a patriot, Sadie—’ and Sadie finally lowered her eyes and said, ‘No, your problem is that I was too jittery last night to fuck you. So I think I’ll do that now,’ and Ada was nervous, which was new, or old, a memory of what she used to feel like before sex and she started to sing again but she couldn’t get the words out because Sadie opened her up and their morning held on.

Two

30/08/2017

Hey, sorry I know it’s weird to message someone I don’t know on Facebook but I saw you at the gig last night and your song really blew me away! I’ve been going to stand-up and cabaret shows every night all month and it was all really samey but you were so good and you said you don’t even usually sing. That might have been a lie now I think about it. Anyway I hope you had a good festival, I’ll definitely come see you perform again if I can. I wish I’d seen the play you did.

I just realised I sound like a weird fan creep in my message. ...

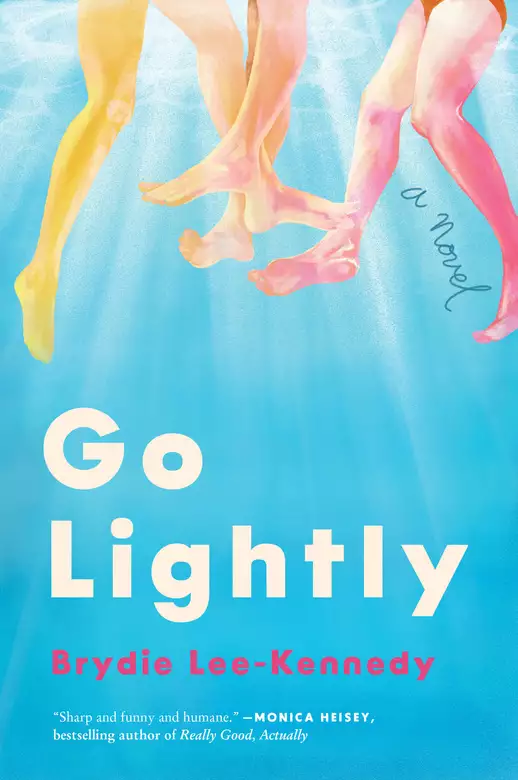

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved