- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

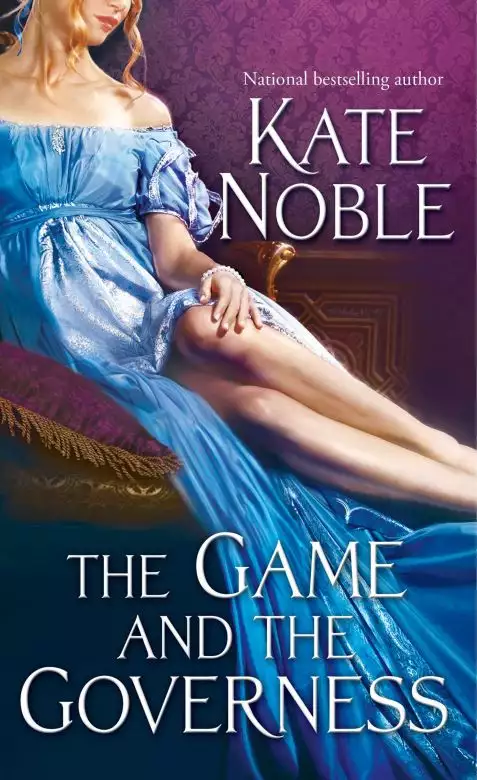

Trading Places meets Pride and Prejudice in this sexy, saucy romance—first in a new series from the author of YouTube sensation The Lizzie Bennet Diaries.

Three friends. One Wager. Winner takes all.

The Earl—‘Lucky Ned’ Ashby. Pompous, preening, certain that he is beloved by everyone.

The Miller—John Turner. Proud, forced to work as the Earl’s secretary, their relationship growing ever more strained.

The Doctor—Rhys Gray. Practical, peace-loving, but caught in the middle of two warring friends.

Their wager is simple: By trading places with John Turner and convincing someone to fall in love with him, Ned plans to prove it’s him the world adores, not his money. Turner plans to prove him wrong.

But no one planned on Phoebe Baker, the unassuming governess who would fall into their trap, and turn everything on its head…

Three best friends make a life-changing bet in the first book in a witty, sexy new Regency trilogy from acclaimed author Kate Noble, writer of the wildly popular Emmy award–winning web series The Lizzie Bennet Diaries.

Release date: July 22, 2014

Publisher: Pocket Books

Print pages: 433

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Game and the Governess

Kate Noble

The Game and the Governess  1

1

It begins with a wager. . . .

LONDON, 1822

It has been said that one should not hire one’s friends.

No doubt, those who have said this have a deep wisdom about life, a spark of intelligence that recognizes inherent truths—or perhaps, simply the experience that proves the veracity of such a statement.

The Earl of Ashby had none of these qualities.

“Determined I was. And luckily, I came of age at the very right moment: I join the army, much to my great-uncle’s dismay—but two days later, Napoleon abdicates and is sent to Elba!”

What the Earl of Ashby did have was luck. In abundance. He was lucky at cards. He was lucky with the fairer sex. He was even lucky in his title.

“Of course, at the time, I did not think of it as lucky, although my great-uncle certainly did, I being the only heir to Ashby he could find in the British Empire. At the time I would have believed that the old man had marched to the Continent and locked Boney up himself to thwart me.”

It was nothing but luck that had the old Earl of Ashby’s son and grandson dying in a tragic accident involving an overly friendly badger, making the nearest living male relative young Edward Granville—or Ned, as he had always been called—the heir to one of the oldest earldoms in the country. It was just such luck that had the old earl swoop in and take little Ned away from the piddling town of Hollyhock and his mother’s genteel poverty at the age of twelve, and raise him in the tradition of the aristocracy.

“But then that French smudge manages to weasel his way off the island, and this time, true luck! I actually get to go to war! But the real luck was getting placed in the same regiment as Dr. Gray here. And— Oh, Turner, stop standing back in the shadows, this story is about you too!”

It was luck, and only luck, that found Ned Granville in the right place at the right time to save his friend and commanding officer, Captain John Turner, as well as seventeen others of their regiment on the last battlefield.

“So there we are in the hazy mist of battle on a field in Belgium, of all places—and thank God too, because I was beginning to think war was going to entirely be marching in straight lines and taking Turner’s and Gray’s money at cards—and suddenly, our flank falls behind a rise and takes a hail of fire from a bunch of Frenchies on top of it.

“So we’re pinned down, waiting for the runner with extra ammunition to arrive, when Turner spots the poor runner shot dead on the field a hundred feet away. And Turner, he jumps up before the rest of us can cover him, and runs out into the field. He grabs the ammunition and is halfway back before a bullet rips through the meat of his leg. There he is, lying on the field, and holding our ammunition. But all I see is my friend bleeding out—so of course, I’m the idiot who runs into the fray after him.”

His actions that day would earn him commendations from the Crown for his bravery. They would also earn Ned Granville his nickname.

“It was just luck that none of their bullets hit me. And once I got Turner back behind the line, and the ammunition to our flank so we could hold our position, we beat the enemy back from whence they came. The next morning, Rhys—Dr. Gray here—had patched Turner up enough to have him walking, and he came over, clapped me on the shoulder, and named me Lucky Ned. Been stuck with it—and him!—ever since.”

It was from that point on that “Lucky Ned”—and everyone else around him—had to simply accept that luck ruled his life.

And since such luck ruled his life, it could be said that Lucky Ned was, indeed, happy-go-lucky. Why bother with worries, when you had luck? Why heed those warnings about hiring your friends? Bah—so bothersome! It would be far more convenient to have a friend in a position of trust than to worry all the time that the servants would cheat you.

Yes, it might breed resentment.

Yes, that resentment might fester.

But not toward Ned. No, he was too good, too lucky for that.

Thus, Ned Granville, the Earl of Ashby, hired his best friend, John Turner, formerly a Captain of His Majesty’s Army, to the exalted post of his secretary.

And he was about to regret it.

They were at a club whose name is not mentioned within earshot of wives and daughters, in their private card room. Well, the earl’s private room. And the earl was engaging in that favorite of his activities: telling the tale of his heroism at Waterloo to a room full of jovial cronies.

But as the night wore on, said cronies moved off to their own vices, and soon only three men remained at the card table: Mr. John Turner, silent and stiff-backed; Dr. Rhys Gray, contemplative and considerate; and the Earl of Ashby, “Lucky Ned,” living up to his name.

“Vingt-et-un!” Lucky Ned cried, a gleeful smile breaking over his features, turning over an ace.

The two other men at the table groaned as they tossed their useless cards across the baize. But then again, the men should be used to such results by now. After all, they had been losing to Ned at cards for years.

“That’s it,” Rhys said, pushing himself back from the table. “I will not play anymore. It’s foolish to go against someone with that much luck.”

“It’s not as if I can help it.” Ned shrugged. “I was simply dealt a better hand.”

“It would be one thing if you shared your luck,” Rhys replied, good-naturedly. “But you have always been the sole man left at the table, even when we were playing for scraps of dried beef in camp.”

“I take exception to that,” Ned replied indignantly. “I do so share my luck. If I recall correctly, Turner here pocketed a number of those beef scraps.”

“And little else since,” John Turner said enigmatically.

Annoyed, the Earl of Ashby gritted his teeth slightly. But perhaps that was simply in response to his latest hand of cards, which the good doctor was dealing out.

“Besides”—Ned instead turned to Rhys—“you were so busy tending to the wounded that you likely saw little of those games. Even tonight you refuse to play for barely more than dried beef.”

“As a man of science, I see little point in games of chance. I have long observed their progress and the only consistent conclusion I come to is that I lose money,” Rhys replied with good humor.

“Little point?” Ned cried on a laugh. “The point is that it’s exciting. You go through life with your observations and your little laboratory in Greenwich and never play for deep stakes. What’s the point of that?” He looked over to the stern-mouthed Turner across from him. “What say you, Turner?”

John Turner looked up from his hand. He seemed to consider the statement for a moment, then . . .

“Yes. Sometimes life is made better by a high-stakes gamble. But you have to choose your moment.”

“There, Turner agrees with me. A rarity these days, I assure you,” Ned replied, settling back into his hand. “Honestly, you are such a stick in the mud of late, Turner, I even thought you might stay home tonight poring over your precious papers—the one night Rhys is in London!”

“If you had chosen to go to any other club, I would have had to,” Turner replied, his voice a soft rebuke. “You know the realities as well as I. And I am afraid being a stick in the mud goes with the territory of being a secretary, instead of—”

The silence that fell on the room was broken only by the flipping over of cards, until Rhys, his eyes on his hand, asked in his distracted way, “Instead of what, Turner?”

A dark look passed between the earl and his employee.

“Instead of a man of my own,” Turner finished.

The earl visibly rolled his eyes.

“Whatever do you mean?” Rhys inquired. As a doctor, he was permanently curious, yet amazingly oblivious to the tension that was mounting in the dark and smoky room.

“He means his mill,” the earl answered for him, taking a loose and familiar tone that might seem odd from a man of the earl’s standing, but that was simply how it was with Ashby. With these two men, the wall had come down long ago.

Or so he had assumed.

“He’s been whining about it for three weeks now. And if you, Turner, had been a mill owner and not my secretary, you would not have been admitted even here . . . so . . .”

“What about the mill?” Rhys asked, looking to Turner.

“My family’s mill has suffered another setback,” Turner sighed, but held his posture straight.

“But I thought you had rebuilt after the fire?” Rhys questioned, his blond brow coming down in a scowl.

“I had, but that was just the building, not the equipment. I sank every penny into purchasing new works from America, but last month the ship was lost at sea.”

“Oh, Turner, I am so sorry,” Rhys began. “Surely you can borrow . . .”

But Turner shook his head. “The banks do not see a mill that has not functioned in five years as a worthwhile investment.”

It went unasked about the other possible source of lending; the source that was present in that very room. But a quick look between Turner and the good doctor told Rhys that that avenue was a dead end as well.

“Turner maintains that if he had the ability to save his family mill, he would be far less of a stick in the mud, and more pleasant to be around. But I have to counter that it simply wouldn’t be true,” Ned intoned as he flipped over an ace.

“You don’t think that working to make my family business a success again, making my own name, would make me more of a pleasure to be around?” Turner asked, his dark eyes narrowing.

“Of course not!” Ned said with an easy smile. “If only for the simple fact that you would be working all the time! That makes no man pleasant.”

“I work all the time now,” Turner replied. “Trust me, running your five estates does not leave me many afternoons free.”

“Yes, everything is always so important,” Ned said dramatically. “All those fields that need dredging require constant updates and letters and all that other nonsense.”

Turner’s mouth formed a hard line. “Far be it from me to bore you with business matters. After all, I was not a man of learning when I took the position. I spent the first three years untangling the old finances and teaching myself the job.”

At the mention of “old finances,” Ned visibly tensed.

“Well . . .” Ned tried, judiciously dropping that line of argument. “At least here you are in London. There is more to do and see here, more to stimulate the mind on one block in London than there can be in all of Lincolnshire.”

“More for you, perhaps.”

“What does that mean?”

“What it means is that the world is different for an earl than it is for his secretary.”

“Fellows,” Rhys tried, finally reacting to the rising voices of his friends. “Perhaps we should just play cards? I would be willing to wager a whole farthing on this hand.”

But they ignored him.

“Don’t be so boring, Turner. Nothing worse than being boring,” Ned said sternly. Then, with relish, “What you need more than anything else is a woman underneath you. Take your stick out of the mud and put it to better use for a few hours. That’ll change your outlook.”

“You might be surprised to learn that most women don’t throw themselves at a secretary with the same frequency they do at an earl.”

“Then buy one.” Ned showed his (very good) cards to the table, exasperated. “There are more than a few in this house who would be willing to oblige. Mme Delacroix keeps her girls clean. Hell, I’ll even pay.”

“Thank you, no.” Turner smiled ruefully. He tossed his cards into the center of the table as Ned raked up his chips. Lucky Ned had won again. “I prefer my companionship earned, not purchased.”

“Which is never going to happen as long as you keep that dour face!” Ned took the cards on the table, gathered them up, and began to shuffle. “And by the by, I resent the implication that I am nothing more than my title.”

“Now, Ashby, he didn’t say that,” Rhys began, but Turner strangely kept silent.

“Yes he did. He said that life is different for an earl than it is for a secretary. And while that is true, it implies that any good thing, any bit of luck I may have had in my life, is incumbent upon the fact that I inherited an earldom. And any lack of happiness Turner suffers from is incumbent upon his recent bad luck. Whereas the reverse is true. He is serious and unsmiling, thus he has bad luck. With his mill, with women, with life. I am in general of a good nature and I have good luck. It has very little to do with my title. It has to do with who I am. Lucky Ned.” A beat passed. “And if I have been too generous with you, Mr. Turner, allow me to correct that mistake.”

The hand that Ned slammed down on the table echoed throughout the room. Eerily quiet, shamed by the highest-ranking man there, the walls echoed with the rebuke. The earl was, after all, an earl. And Turner was dancing far too close to the line.

“I apologize if my words gave the impression that you owe your happier philosophy to your title and not to your nature,” Turner said quietly.

“Good.” Ned harrumphed, turning his attention back to the deal. A knave and a six for himself. An ace for Turner, and a card facedown, which . . .

Turner gave his own set of cards his attention then, and flipped over the king of hearts, earning him a natural. But instead of crying “Vingt-et-un!” like his employer, he simply said quietly, “But the title certainly helps.”

“Oh, for God’s sake!” Ned cried, throwing his cards across the baize.

All eyes in the room fell on the earl.

“Turner. I am not an idiot. I know that there are people in the world who only value me because of my title, and who try to get close to me because of it. That is why I value your friendship—both of you. And why I value the work you do for me, Turner. It’s all too important to have someone I can trust in your role. But I thoroughly reject the notion that all of my life is shaped by the title. I didn’t always have it, you know. Do you think Lady Brimley would have anything to do with me if I was nothing more than a stuffed-shirt jackanape?”

At the mention of the earl’s latest entanglement—a married society woman more bored even than Ned, and most willing to find a way to occupy them both—Turner and Rhys cocked up similar eyebrows.

“So you are saying your prowess with women is not dependent on your title either?” Turner ventured calmly.

“Of course it’s not!” Ned replied. “In my not insignificant experience—”

At this point, the good doctor must have taken a drink in an ill manner, because he suddenly gave in to a violent cough.

“As I was saying . . .” Ned continued, once Rhys apologized for the interruption. “In my not insignificant experience, when it comes to women, who you are is far more important that what you have.”

He took in the blank stares of his friends.

“Go ahead, call me romantic.” Ned could not hide the sardonic tone in his voice. “But if a woman found me dull, boring, or, God forbid, dour like you, I would not last five minutes with them, be I a prince or a . . . a pauper!”

“Well, there is certainly something about your humble charm that must woo them,” Rhys tried kindly, his smile forcing an equal one out of Ned.

But Turner was quiet. Considering.

“I promise you, Turner, it is your bad attitude that hinders you—be it with women or bankers. It is my good attitude that brings me good luck. Not the other way around.”

“So you are saying you could do it?” Turner asked, his stillness and calm eerie.

“Do what?”

“Get a woman to fall for you, without a title. If instead you were, say, a man of my station.”

Ned leaned back smugly, lacing his hands over his flat stomach. “I could do it even if I was you. It would be as easy as winning your money at cards. And it would take less time too.”

It happened quickly, but it was unmistakable. Turner flashed a smile. His first smile all evening.

“How long do you think it would take?” he asked, his eyes sparks in the dark room.

Ned leaned back in his chair, rubbing his chin in thought. “Usually the ladies start mooning after me within a few days. But since I would be without my title, it could take a week, I suppose, on the outside.”

Turner remained perfectly still as he spoke. “I’ll give you two.”

Rhys’s and Ned’s heads came up in unison, their surprised looks just as evenly matched. But Rhys caught the knowing look in Turner’s eyes, and made one last effort at diplomacy between his two sparring friends.

“Turner—Ned . . .” Rhys tried again, likely hoping the jovial use of Ned’s Christian name would snap him out of it, “I am in London so rarely and only for a night this trip. Can we not just play?”

“Oh, but we are playing,” Turner replied. “Can’t you see? His lordship is challenging me to a wager.”

“He is?”

“I am?” Ned asked. “Er, yes. Yes, I am.”

“You have just said that you can get a lady to fall for you within a week, even if you are a man of my station. Hell, even if you are me, you said.”

“So . . .”

“So, we trade places. You become me. Woo a lady and win her. And I offer you the benefit of two weeks—which should be more than enough by your estimation.”

“But . . . what . . . how—” Ned sputtered, before finally finding his bearings again.

And then . . . he laughed.

But he was alone in that outburst. Not even Rhys joined in.

“That’s preposterous,” Ned finally said. “Not to mention undoable.”

“Why not?”

“Well, other than the fact that I am the earl, and everyone knows it.”

“Everyone in London knows it. No one in Leicestershire does.”

“Leicestershire?” Rhys piped up. “What on earth does Leicestershire have to do with this?”

“We go there tomorrow. To see about Ashby’s mother’s old house in Hollyhock.”

“Hollyhock?!” Ned practically jumped out of his chair. It was safe to say any hand of cards had well been forgotten at this point, as the wager currently on the table was of far greater interest. “Why the hell would I want to go to Hollyhock?”

“Because the town has a business proposal for the property, and the land and building must be evaluated before you decide what to do with it,” Turner replied sternly. “I cannot and will not sign for you. That was a rule very strictly laid down by yourself, and with good cause, if you recall.”

The trio of heads nodded sagely. The Earl of Ashby did have good reason to be cautious with his larger dealings, and to have someone he trusted in the role of his secretary. And the sale of his mother’s house in Hollyhock did qualify as a “larger dealing.”

“By why on earth should I go to Hollyhock now? At the height of the season? For heaven’s sake, Lady Brimley’s ball is next week, I would be persona non grata to her . . . charms, if I should miss it.”

“I scheduled the trip for now because of Lady Brimley’s party,” Turner offered. Then, pointedly, “At which she has engaged Mrs. Wellburton to sing.”

At the mention of the earl’s previous paramour—an actress with a better figure than voice, but an absolutely astonishing imagination—Ned visibly shifted in his seat.

“Yes, well . . . perhaps you are right. Perhaps now is the best time to be out of London. If you catch my meaning.”

“We catch your meaning, Ashby,” Rhys replied. “As easily as you are going to catch syphilis.”

Ned let that statement pass without comment. “Well, what’s the proposal about?” Ned asked, before waving the question away. “No, I remember now. Something to do with a hot spring. But, God, Hollyhock. Just the name conjures up images of unruly brambled walks and an overabundance of cows. I cannot imagine a more boring way to spend a fortnight. I haven’t even been there since I was twelve.”

“So there is no reason to expect that anyone would recognize you,” Turner replied.

“Well, of course they will recognize me,” Ned countered. “I’m me.”

“The physical difference between a boy of twelve and a man full grown is roughly the same as for the boy of twelve and the newborn,” Rhys interjected, earning him no small look of rebuke from Ned.

“Even if that is so, I look like me, and you look like you,” Ned tried, flabbergasted.

“And who is to say we do not look like each other?” Turner shrugged. “We are of a height, and both have brown hair and brown eyes. That is all the people of Hollyhock will remember of a boy long since grown into adulthood. And besides”—Turner leaned in with a smile—“I doubt you would find the trip to Hollyhock boring if I’m you and you are me.”

“There is the small issue of your speech,” Ned said suddenly. “Your accent is slightly more . . . northern than mine.” Which was true; when Ned had been taken from Leicestershire and raised by his great-uncle, any hint of poverty in his accent was smoothed out. Turner, having been born in the rural county of Lincolnshire and raised in trade, had an accent that reflected his lower-class upbringing.

But it appeared he had learned a thing or two in the interim. When he next opened his mouth, Turner spoke with the melodic, cultured tones of a London gentleman.

“I doubt it will be a problem,” Turner said—his accent a perfect mimic of Ned’s!—with a smile. “But if someone manages to discern our ruse by my speech, I will forfeit, and you will win.”

“Gentlemen,” Rhys broke in. “This is a remarkably bad idea. I cannot imagine what you could possibly hope to learn from the experiment.”

“I shall enlighten you,” Turner replied. “If the earl is correct, he will have taught me a valuable lesson about life. If he can, simply through his natural good humor, win the heart of a young lady, then there is obviously no reason for me to take the hardness of life so seriously. But if he is wrong . . .”

“I am not wrong,” Ned piped up instantly, his eyes going hard, staring at Turner. “But nor am I going to take part in this farce. Why, you want to switch places!”

Rhys exhaled in relief. But Turner still held Ned’s gaze. Stared. A dare.

A wager.

“But . . . it could be interesting,” Ned mused.

“Oh, no,” Rhys said into his hands.

“If we could actually pull it off? Why, it could be a lark! A story to tell for years!”

“You do enjoy telling a good story,” Turner said with a placid smile.

“And I get to teach you a lesson at the same time. All the better.” Then Ned grinned wolfishly. “What are your terms?”

Turner, even if his heart was pounding exceptionally fast, managed to contain any outside appearance of it. “If you are not so fortunate as to win the heart of a female . . .” He took a breath. “Five thousand pounds.”

Rhys began coughing again.

“You want me to give you five thousand pounds?” Ned said on a laugh. “Audacious of you.”

“You are the one that said life is nothing without the occasional high stakes.”

“And you are the one who said one must choose his game carefully. Which it seems you have. Still, such a sum—”

“Is not outside of your abilities.” His smile grew cold. “I should know.”

“And what if I am right?” Ned leaned forward in his chair, letting his cool voice grow menacing. “What if I win?”

Turner pricked up his eyebrow. “What do you want?”

Ned pretended to think about it for a moment. “The only thing you have. The only thing you care about.” Ned watched as Turner’s resolve faltered, ever so slightly. “I’ll take that family mill off your hands. Free you to a life of better living and less worry.” He mused, rubbing the two-days’ beard on his chin again. “As it’s not functioning, I suppose it’s worth a bit less than five thousand, but I’m willing to call that even.”

Turner remained still. So still. A stillness he’d learned in battle, perhaps. Then he thrust his hand across the table.

“I accept.”

“No! No, this is madness,” Rhys declared as he stood. “I will not be a party to it.”

“I am afraid you have to be,” Turner drawled. “You are not only our witness, but you will have to serve as our judge.”

“Judge?” Rhys cried, retaking his seat as he hung his head in his hands.

“Yes—you can be the only person impartial enough to do it.” He turned to Ned. “Is that agreeable to you, my lord?”

“Yes. That will suit me,” he answered back sharply, stung by Turner’s tone.

“So we are agreed, then? It is a wager?” Turner asked, his hand still in the air, waiting to be shook.

“It is.” Ned took the hand and pumped it once, firmly. “Good luck,” he wished his old friend. “Out of the two of us, you are the one that will need it.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...