- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

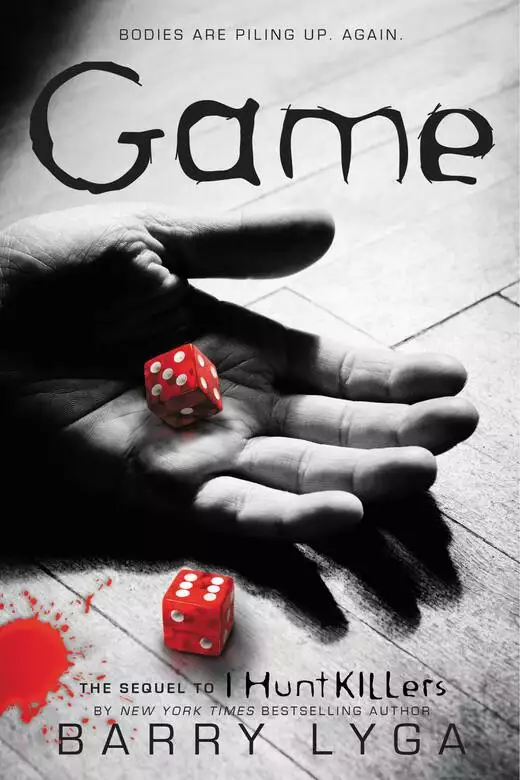

Several months have passed since Jazz helped the Lobo’s Nod police force catch the serial killer known as the Impressionist. Every day since then, Jazz has dealt with the guilt of knowing he was responsible for his father’s escape from prison. Now Billy Dent is on the loose, ready to kill again. Jazz’s reputation has spread far beyond the borders of his sleepy hometown, and when a determined New York City detective comes knocking on Jazz’s door asking for help with a new case, Jazz can’t say no. The Hat-Dog Killer has the Big Apple in a panic, and the police are running scared. Jazz has already solved one crime, but at a high cost. Innocent people were murdered because of him. Is the Hat-Dog Killer his means of redemption? Or will Jazz get caught up in a killer’s murderous game? And somewhere out there, Billy is watching … and waiting. From acclaimed author Barry Lyga comes the heart-stopping sequel to I Hunt Killers—and this time, both the stakes and the body count are higher.

Release date: June 17, 2014

Publisher: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

Print pages: 528

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Game

Barry Lyga

Well, it didn’t matter. Not anymore. Not right now. Names were labels for things, the killer knew. Nouns. Person, place, thing, idea—just like you learned in school. See this thing I drink from? I give it the label of “cup,” and so what? See this thing I cover my body with? I give it the label of “shirt,” and so what? See this thing I have opened to the darkening sky, allowing beautiful moonlight to shine within? I give it the label of “Jerome Herrington,” and so what?

The killer stood and stretched, arching his back. Carrying the thing labeled Jerome Herrington up five flights of stairs hadn’t been easy; his muscles were sore. Fortunately, he wouldn’t have to carry the thing labeled Jerome Herrington back down.

The thing’s head twisted left and right, the eyes staring straight ahead, unblinking. Unblinking because they had no choice—the killer had removed the eyelids first. Always first. Very important.

The killer crouched down near the thing’s head and whispered, “We’re very close now. Very close. I’ve opened your gut, and I have to say—you’re beautiful in the moonlight. So very beautiful.”

The thing labeled Jerome Herrington said nothing, which the killer found rude. And yet the killer was not angry. The killer knew what anger was, but had never experienced it. Anger was a waste of time and energy. Anger was useless. “Anger” was the label given to an emotion that accomplished nothing.

Maybe the thing labeled Jerome Herrington simply did not and could not appreciate its own beauty. The killer pondered a moment, then reached down and lifted a blood-slippery mass of intestines from the thing’s open cavity. Moonlight glinted on the shiny, gray-red loops.

The thing labeled Jerome Herrington groaned with deep and abiding agony. It raised its head, straining as though to escape, barely able to keep its head aloft.

The thing blubbered. Tears streamed down its cheeks and it tried to speak.

The killer beamed. The thing sounded happy. That was good.

“Almost done,” the killer promised, dropping the guts. At the same moment, the thing’s neck gave out and its head dropped. Kunk! went one. Splet! went the other.

The killer slid a small, sharp knife from his boot. “I think the forehead,” he said, and began to carve.

It was a cold, clear January day when they gathered to bury Jazz’s mother.

Bury was probably the wrong word; there was no body. Janice Dent had disappeared more than nine years ago, when Jazz was eight, and hadn’t been seen since. The world knew she was dead; the courts had declared her dead after the requisite seven-year waiting period. Jazz just hadn’t been able to bring himself to take the final step.

A funeral.

As the only child of the world’s most notorious serial killer, he’d grown up with an intimate understanding of the mechanisms and the causes of death. But, strangely enough, he’d never attended a funeral until now.

This was poetic justice, in a way: Many of his father’s victims had had funerals without bodies, too. They would have had more mourners, of course. For Janice Dent, wife of Billy, there were fewer than a dozen people. The press, fortunately, was held back at the cemetery gate.

No one would cry for Janice Dent. Not today. Her parents were long dead, and she’d been an only child. She had no friends left in Lobo’s Nod that Jazz knew of, at least no one who had come forth when the funeral had been announced. Jazz figured this was fitting; she had vanished alone, and now she would be buried alone.

Next to him, his girlfriend, Connie, squeezed his hand tightly. On the other side of him stood G. William Tanner, the sheriff of Lobo’s Nod and the man who had brought Billy Dent to justice more than four years ago. He was the closest thing Jazz had to a father figure, an irony that Billy would probably have laughed at. That was just Billy’s sense of humor.

“Dear Lord,” the priest said, “we ask that you continue to look over our beloved sister Janice in your kingdom. She has been gone from us for a while, O Lord, and we know you have watched over her in that time. Now we ask you to watch over us, as well, as we grieve for her.”

Jazz found himself in the strange position of wanting this to be over as quickly as possible, for the priest to wrap things up and let them all go. Ever since Lobo’s Nod’s assault by the Impressionist—a Billy Dent wannabe—and then Billy’s escape from prison into the wide world a couple of months ago, Jazz had felt a burning need to close off as much of his past as possible. He knew the future portended a brutal reckoning (Billy had been quiet, but that wouldn’t last), so he wanted his past put to rest. Finally acknowledging his mother’s death was the biggest step he’d taken so far.

Jazz hadn’t cared which faith buried his mother; Father McKane at the local church had been the most willing to perform the service, so Jazz had gone Catholic. Now, as the priest droned on and on, Jazz wondered if he should have held out for a less verbose brand of religion. He sighed and gripped Connie’s hand and stared straight ahead at the casket. It contained a bunch of brand-new stuffed animals, similar to the ones Jazz remembered his mother buying him as a child. It also contained a batch of lemon-frosted cupcakes Jazz had baked. That was his strongest memory of his mother—the lemon-frosted cupcakes she used to bake. He could have just had a service and a stone, but he’d wanted the whole experience, the totality of the funeral ritual. He wanted to witness the literal expression of burying his past.

Sentimental? Probably. And what of it? Bury it all. Bury the memories and the sentiment and move on.

Arrayed around the cemetery, he knew, were more than a dozen police officers and federal agents. Once the authorities had gotten wind of Jazz’s plan to hold a funeral service for his mother, they had insisted on staking it out, certain (or maybe just hopeful) that Billy wouldn’t be able to resist this opportunity to emerge from hiding. It was a waste of time, Jazz had told them, his insistence as useless as a sledgehammer against a tidal wave.

Billy would never reveal himself for something as prosaic and predictable as a funeral. He had occasionally attended the funerals of his victims, but that was before cable news had splashed his face on HD screens all around the world. “Butcher Billy” was too smart to show that famous face here, of all places.

“We’re going to make a go of it, anyway,” an FBI agent had told Jazz, who had shrugged and said, “You want to waste tax dollars, I guess that’s your prerogative.”

Finally the priest finished up. He asked if anyone would like to say anything at the grave, looking pointedly at Jazz. But Jazz had nothing to say. Nothing to say in public, at least. He’d come to terms with his mother’s death years ago. There was nothing left to say.

To his surprise, though, the priest nodded and pointed just over Jazz’s shoulder. Jazz and Connie both turned—he caught the shock of her expression, too—and watched as Howie Gersten, Jazz’s best friend, threaded carefully between G. William and Jazz, studiously avoiding meeting Jazz’s eyes. Dressed in a black suit with a somber olive tie, six foot seven at the age of seventeen, Howie looked like a white-boy version of the images Jazz had seen of Baron Samedi, the skeletal voodoo god of the dead. The suit jacket was slightly too short for Howie’s ridiculously long limbs, and a good two inches of white shirt cuff and pale wrist jutted out.

“My name is Howie Gersten,” Howie said once he’d gotten to the gravestone. Jazz almost burst out laughing. Everyone here knew who Howie was already. “I didn’t know Mrs. Dent. But I just really feel like when you bury someone, when you say good-bye, that someone should say something. And I figure that’s my job as Jazz’s best friend.” Howie cleared his throat and glanced at Jazz for the first time. “Don’t be pissed, dude,” he stage-whispered.

A ripple of laughter washed over the attendees. Connie shook her head. “That boy…”

“Anyway,” Howie went on, “here’s the thing: When I was a kid, I used to get pushed around a lot. I’m a hemophiliac, so I have to be careful all the time, and when you combine that with being a gangly string bean, it’s like you’re just asking for trouble, you know? And I wish I could tell you that Mrs. Dent was nice to me and used to say kind and encouraging things to me when I was going through all of that, but like I said, I didn’t know her. By the time I met Jazz, she was already, y’know, not around.

“But here’s the thing. Here’s the thing. And I think it’s an obvious thing, but someone needs to say it. We all know that, uh, Jazz’s dad wasn’t, isn’t, exactly a great role model. But there I was one day when I was like ten or something and these kids were having a fine old time poking bruises into my arms. And Jazz came along. He was smaller than them and outnumbered, and let’s face it—I wasn’t going to be much help—”

Another ripple of laughter.

“But Jazz just waded into those douchebags—um, sorry, Father. He just waded into them and kicked their, um, rears, which I know isn’t terribly Christian or anything, but I’ll tell you, it looked pretty good from where I was standing. And I guess the thing is—the obvious thing that I mentioned before is—that I never met Mrs. Dent, but I know she must have been a good person because I’m pretty sure Billy Dent didn’t raise Jazz to rescue helpless hemophiliacs from bullies. And that’s all I have to say. I’ll miss you, Mrs. Dent, even though I never met you. I wish I had.” He started to walk back to the group of mourners, then stopped and said, “Um, God bless you and amen and stuff,” before hustling back to his spot.

And then they lowered the casket into the ground. The stone said JANICE DENT, MOTHER. No dates, because Jazz couldn’t be sure exactly when Billy had killed her.

He took the small spade from the priest and shoveled some dirt into the grave. It rattled.

G. William and Connie and Howie followed suit. Then they backed away so that the cemetery workers could do the real shoveling.

Jazz became aware that he was staring at the shovels as they heaved dirt on top of the casket that did not hold his mother’s body, snapping out of it only when Connie poked him to get his attention. She held a tissue out for him.

“What’s this for?” he asked, taking it automatically.

“Your eyes,” she said, and Jazz realized that—much to his surprise—he was crying.

Jazz’s grandmother was waiting for him when he got home, sitting on the porch in a rocking chair, a blanket thrown over her legs. From all appearances, she looked like just another old lady enjoying a crisp day in January.

“They’re here,” she whispered to Jazz as he mounted the front steps. “They’ve come for your daddy.”

Jazz wasn’t sure who she meant when she said “your daddy.” Gramma was delusional enough that she sometimes thought Jazz was Billy, meaning that she could think “they” had come for Jazz’s long-dead grandfather. Or she could be lucid enough to think that the “they” in question—actually Deputy Michael Erickson, who had volunteered to keep an eye on Gramma during the funeral—were here for Billy himself. Which meant that Gramma’s thinking was roughly on par with the FBI’s these days. Jazz wasn’t sure if that was funny or sad.

He could see Erickson peering out at them from the corner of a window. Gramma had hated Mom, so there was no way in the world Jazz was going to have her at the funeral. And even if Gramma had loved Janice, when given the choice between inviting his black girlfriend or his insane, racist grandmother, Jazz would choose Connie every time.

“They sent spies,” Gramma went on, her voice a hush, “and they look like one man, but they can split into two, then four, and so on. I’ve seen it before. During the war. It’s a Communist trick and they taught it to the Democrats so that they could take our guns. I would have fought them off, but they already made the shotgun disappear.”

No, Jazz had made the shotgun disappear. It was Grampa’s old hunting piece, and Jazz had plugged both barrels and removed the firing pins so that Gramma couldn’t really hurt anyone with it. But when he was going to be gone for a long stretch—like today—he made sure to hide it from her. It was nice to know that she was blaming Washington politicians and not him.

Years of dealing with Gramma’s progressively deteriorating mental state had rendered Jazz pretty much impervious to shock. “So, there’s a commie spy in the house looking for Dad, huh?” he said. There’s a sentence I never thought I’d hear myself say. “Don’t worry. I’m gonna go in there and run him out. He won’t dare come back by the time I’m done with him.” He brandished the ceremonial spade the priest had given him at the end of the service as though it were a samurai sword.

Gramma’s eyes widened, and she clapped her hands. “Gut him!” she yelled. “Gut him like that raccoon you gutted on Fourth of July that one year!” And she made vicious stabbing and hacking motions as Jazz went inside.

“How’s it going?” he asked Erickson. “Other than the usual.”

Erickson shrugged. “She started bugging out about an hour ago. I just decided to go with it. As long as I could keep an eye on her from in here, I figured it was better just to let her sit outside.”

“Good call. She thinks you’re some kind of Communist clone, by the way.”

Erickson laughed. “That explains a lot.”

“Anyway, I’d consider it a big personal favor if you could sort of run like hell on your way out of here.”

“For you? Anything.”

Jazz felt a pang of guilt. Erickson was a good cop, relatively new to the tiny town of Lobo’s Nod, transferring in right as the Impressionist had begun his string of Billy Dent–inspired murders. To his eternal shame, Jazz had suspected Erickson in the crimes and hadn’t been shy about letting the sheriff know it. After that, he figured he was the one who owed Erickson, but the deputy didn’t see it that way. As far as Erickson was concerned, Jazz’s deducing and rescuing the Impressionist’s next victim made him a hero.

“Thanks again for watching her.”

“Take care of yourself, Jasper.” Erickson opened the door and then burst through as if chased by demons, screaming in a hilariously high voice all the way to his squad car.

Gramma minced into the house, peering around. “He didn’t leave any little baby spiders, did he? They’re tiny mind-controllers, and they crawl into your ears while you’re asleep and rewire your brain until you don’t know who you are anymore.”

Ah, so that’s what had happened to Gramma.… Jazz sighed. She was getting worse. He’d always known she was getting worse, but somehow he’d convinced himself that her madness was manageable and harmless. Once upon a time not long ago, a social worker named Melissa Hoover had moved heaven and earth to get Jazz removed from Gramma’s house to a foster home. Jazz had resisted, and then Billy—after his escape from prison—had killed Melissa before she could submit her report, putting an end to that particular problem.

For now.

The fact of the matter was that soon enough Social Services would get around to assigning another caseworker to Jazz. He still had six months until his eighteenth birthday—they could still yank him from Gramma’s house. And Jazz was beginning to think that maybe Melissa had been right after all. Maybe he needed to be out of this environment. Away from his grandmother. Away from Lobo’s Nod, even. Away from all the memories of his childhood and of Billy.

Oh, who was he kidding? Billy was out there in the world somewhere. As long as Billy was free, Jazz could never escape his past. His father would, he knew, find him and contact him. Somehow. Some way. No matter how many cops and FBI agents were looking for him and surveilling Jazz, Billy would find a way.

Jazz settled Gramma in the parlor in front of the TV. The first channel he happened to see was local news. Doug Weathers—sleazebag reporter par excellence—was speaking to the camera: “—funeral of Janice Dent, wife of the notorious William Cornelius Dent, also known as the Artist, Green Jack, Hand-in-Glove, and many other aliases. The press was not invited, but we can tell you that the service was brief and sparsely attended—”

Jazz quickly flipped over to a shopping channel. Gramma found them hilarious.

In the kitchen, he started washing the dishes Gramma had used while he was gone. Erickson had stacked them neatly in the sink for him, a far cry from Gramma’s latest habit of sticking them in the broiler. As he soaped and sponged them, he gazed out the kitchen window at the backyard.

And the birdbath.

You know that old birdbath my momma’s got in her backyard?

Billy. In the visitation room at Wammaket State Penitentiary.

She’s got it oriented to a western exposure. See? It’s not gettin’ the morning light, and that’s what them birds want. It needs to be moved to the opposite edge of the lawn.

They’d argued. Jazz had felt like an idiot, arguing with his sociopathic mass-murdering father about a birdbath.…

Just move the damn thing. Go when she’s asleep and just move it. You know, where that big ol’ sycamore sits.

And this, Jazz had said with incredulity, is the price of your help?

And it had been. And so Jazz had done as Billy had commanded. Even now, months later, he wasn’t sure exactly why. Billy had no way of enforcing the favor he’d asked, after all. But Jazz had felt honor bound to do it. As though not moving that damn birdbath would have proven that he was an uncaring, unfeeling sociopath like Dear Old Dad, would have cemented his fate. So he’d moved it, and that very night Billy had broken out of prison.

Soon after the escape and its horrifying aftermath, Jazz had come clean to G. William, confessing to the sheriff that he’d done a favor for Billy. “I don’t see how it could be connected,” he’d said. “But I also don’t see how it couldn’t be.”

The next day—much to Gramma’s deluded consternation—a team made up of local cops and FBI analysts had descended on Jazz’s backyard. They dug up the ground where the birdbath had rested for years. They dug up the ground under its current location. They took sightings with surveyors’ tools along multiple angles, checking to see who or what might have a clear line of sight to the birdbath.

And they had also examined the birdbath itself, ultimately discovering the truth that destroyed Jazz.

Four screws held part of the fountain casing in place. Three of them were old and tarnished, but one was newer, still shiny. A bomb expert was called in—just in case—and when the screws were removed and the mechanism disassembled, they found…

“A GPS transmitter,” G. William told Jazz later that night in the sheriff’s office, where he’d summoned Jazz. “Pretty good one, too. Accurate to five meters.”

“Or one backyard,” Jazz muttered.

“Well…” G. William clearly didn’t want to confirm it. The big man’s florid, misshapen nose—bashed out of normalcy after a lifetime of being a cop—went bright red as the rest of his face paled. “Well, yeah.”

“So I move the birdbath and somewhere in the world, Billy’s lunatic confederate sees the Bat-signal and realizes it’s time to spring his Lord and Master from Wammaket. Next thing you know, there are dead guards—”

“Corrections officers,” G. William emended.

“Corrections officers, right, and Billy is in the wind.”

Billy’s escape gnawed at him with rat teeth. Obviously, he would rather Dear Old Dad stay behind bars, leaving Wammaket only when zipped up into a nice little body bag all his own. But Melissa… and the deaths of the COs… ah, now those chewed at him with saber-tooth fangs. Was he responsible for their deaths? In a manner of speaking, sure—he had set in motion the events leading to Billy’s escape, and the COs and Melissa had died as a result of that escape. But Jazz himself hadn’t killed them. The corrections officers had died during a mini-riot that covered Billy as he broke out of the infirmary and made his way outside. And Melissa had died ugly, at Billy’s own hand. Even if Jazz had known that moving the birdbath would mean Billy’s escape, could he reasonably have assumed people would die in the process?

He didn’t know. That didn’t stop him from feeling guilt, though.

Unless it wasn’t really guilt.

They got all these emotions, Billy had told him once. Things like love and fear and compassion and regret. They got ’em deep inside, all twisty and tight like a knot of living snakes. They think they’re in control of themselves, but they really just do what the snakes tell them.

“They,” of course, were ordinary people. Sheep. Potential victims. Prospects was the word Billy used to describe them. And their emotions? Well, those things were useless for people like Billy, but it was important to know how to fake them.

Is that what I’m doing? Jazz wondered. I know I should feel guilty for getting those people killed. And Billy spent my whole life teaching me how to pretend to feel things I wasn’t really feeling. Am I just fooling myself? Am I just acting guilty because that’s how I’m supposed to act? What is it really supposed to feel like?

Maybe Connie would know. Maybe Connie could describe it to him. Help him understand.

Maybe.

Almost against his will, he had shared more with Connie than he’d ever intended. He’d told her about the dreams, for example, the dreams in which he held a knife and cut… something. Or someone. He didn’t know for sure. He’d wondered for the longest time who he’d been cutting in the dream. Maybe it was his mother, he’d wondered. Maybe he had killed her.…

But the last time he’d seen Billy, his father had seemed to deny that, saying that Jazz was a killer… just one who hadn’t killed yet. It was typical Billy double-talk, the kind of stuff Billy had said all of Jazz’s life, words defined and redefined and misdefined to break down Jazz’s natural inhibitions. People out there ain’t real, Billy would say. They ain’t really real, not real like you’re real or I’m real. They’re real in their own false way. They think they’re real, but they only get to think it because we let them, you see?

Classic brainwashing tactics. Cults used them. Heck, most established religions did, too. The human mind was a horribly fragile thing—breaking it and reassembling it in a new order was so easy it was depressing.

People are real, Jazz told himself, repeating his mantra. People matter.

In the dream, though, nothing mattered. Nothing, that is, except for bringing down the knife, his father’s voice urgent, the knife meeting the flesh… then parting it…

That dream was bad enough. But the new one… the one that had started the very night Billy escaped, the night Jazz met and defeated the Impressionist…

—touch—

—his hand runs up—

Oh, yes, you know—

—touching—

—you know how to—

The doorbell rang. Thank God.

Jazz got to the door before Gramma could, calming her as he cut through the parlor. “It’s just the doorbell,” he told her.

“Air raid!” Gramma screamed. “Air raid! Commie missiles!”

“Doorbell,” Jazz assured her. “Look—Bowflex on TV!”

Gramma swiveled and hitched in a breath at the sight of an oiled bodybuilder doing bench presses. “Muscles!” she shouted, and clapped like a little girl.

Jazz peered through the small window next to the door and heaved a sigh of relief that Gramma hadn’t made it to the door first—the man on the porch was black, and Gramma’s notion of racial tolerance hadn’t evolved past the late forties. The eighteen-forties.

The man was unfamiliar, but Jazz recognized the stance, the poise. Not a reporter, thank God. The guy was a cop of some variety. Maybe even an FBI agent. In any event, it was no one Jazz wanted to talk to. He would have to shoo the guy off—if he just ignored him, he would ring the bell again and set Gramma off.

So he opened the door a crack and focused his sternest gaze out onto the porch. “We gave at the office. I don’t like Girl Scout cookies. No, I would not like a copy of The Watchtower—we’re Buddhist. Thanks and bye.”

Before he could get the door closed, though, the cop moved with practiced ease and jammed his toe in the gap. “You don’t work at an office. You were raised Lutheran. And what on earth do you have against Thin Mints?”

Jazz pushed against the door. Nothing doing. The cop was wearing steel-toed boots; he could stand there all day. “You caught me. I just don’t like cops.”

“Neither do I,” the man said with forced joviality. “Come on, kid.” His voice became suddenly earnest, almost pleading. “Give me five minutes. I promise I’ll leave you alone after that.”

“Last person I opened this door for turned out to be doing his best impersonation of my father. You understand why I’m hesitant.”

The man flipped open a small leather folder to reveal his badge. “I came all the way from New York to see you. Should be, like, a two-hour flight, but the department’s so damn cheap, would you believe I had to make two connections? Took more like five hours. Plus, I had to rent a car. And I hate driving like you hate your pops. Five minutes. I swear on my badge.”

Jazz scrutinized the badge. Looked authentic, as best he could tell. He’d never seen an actual NYPD badge, but he knew the basics. The ID card next to it had a lousy photo of the man on the porch, along with his name and rank: LOUIS L. HUGHES, DET. 2ND/GRADE. NYPD. BROOKLYN SOUTH. HOMICIDE DIVISION.

Despite himself, he was intrigued. New York. A New York cop. What could he—

Ah. Ah, he got it.

“This is about Hat-Dog, isn’t it?”

“Five minutes. That’s all.”

That toe wasn’t going anywhere, and as long as it stayed, Hughes would stay, too. Jazz sighed and opened the door. Before Hughes could step in, Jazz pushed him back and joined him on the porch, closing the door behind.

“It’s getting cold out here,” Hughes complained.

“I would invite you in, but my grandmother is an insane racist.”

A snort. “As opposed to all those nice, sane racists out there?”

Jazz folded his arms over his chest. “Your five minutes started thirty seconds ago. We can talk about the historic injustices that continue to be visited upon the African American community to this day, or you can talk about Hat-Dog.”

Hughes nodded. “What do you know already?”

Jazz shrugged. “Just what’s been on the news. Which means probably less than anything real or relevant.” They shared a grimace of disdain for the media. “First killing was about seven months ago. There’ve been a total of fourteen so far. Most in Brooklyn. All show signs of a mixed organization killer—he’s good at covering his tracks, but he goes buck wild on the bodies. Lots of mutilation. Maiming. Details withheld by the police ‘to weed out possible false leads.’ ” Jazz thought for a moment. “I bet he’s started disemboweling them, right?”

Hughes did a good job covering his surprise, but not so good that Jazz couldn’t tell. “Yeah. How did you know that? That’s one of the things we kept out of the news.”

“Reading between the lines. There was a quote in one news story from the medical examiner, talking about ‘a real mess.’ And in the background of one of the pictures in the paper, you can see a CSI with a covered bucket. I played the odds.”

Hughes pressed his lips together. “Not bad. Yeah, he’s started disemboweling them.”

“And his deal is he marks them, right? Didn’t I read that? Some of them with a hat, some with a dog? Cuts it into them.”

“Yeah. There’s no pattern to that. At first we thought he was alternating, or marking the women with hats and the men with dogs. That would fit a certain sort of pathology. But then we got a dog on a woman. Then two hats in a row. And a hat on a man. And then another couple of hats in a row. There’s no pattern to it.”

“There’s a pattern to it,” Jazz said. “It’s just not one that you can see.”

“And you can?”

“I didn’t say that. It makes sense to him, though.”

“I know,” Hughes said testily. “I’m not right out of the academy. In this guy’s head, the most sensible thing in the world is to grab up people and torture them and kill them and carve hats and dogs on them. I get it.”

Jazz looked at his watch. “There’s your five. I hope it was worth it.”

“Wait!” Hughes threw out a beefy arm, blocking the front door. “Look, I didn’t come here to gab with you on your front porch. I need—we, that is. We need your help.”

Jazz laughed. “My help? What, because I caught the Impressionist? That was sort of a special circumstance.”

“Oh? How so?”

“He was imitating my father. He was practically killing people in my backyard.”

“I get it—so you only take the easy ones. And the people of New York just don’t count. They might as well not be real to you.”

People are real. People matter.

Words to live by, for Jazz. He had no other choice—the moment he stopped believing that (and it would be depressingly easy to do so, he feared) would be the moment he turned into his father.

But, yeah, peopl

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...