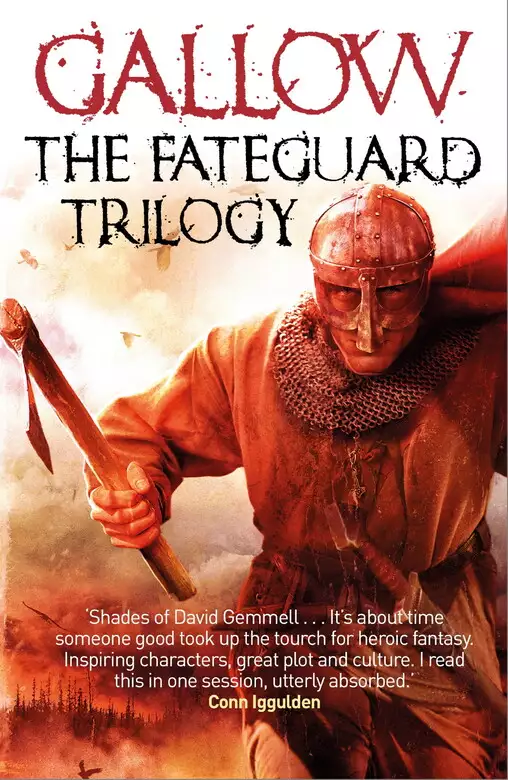

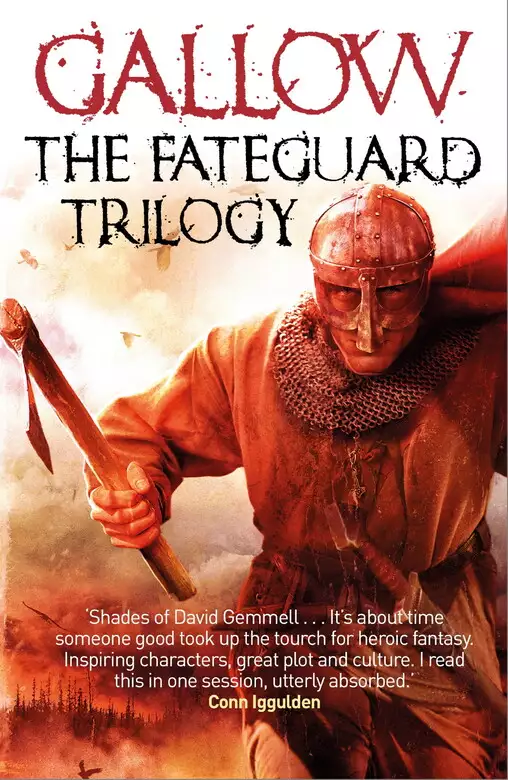

Gallow: The Fateguard Trilogy eBook Collection

- eBook

- Paperback

- Set info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

I have been Truesword to my friends, Griefbringer to my enemies. To most of you I am just another Northlander bastard here to take your women and drink your mead, but to those who know me, my name is Gallow. I fought for my king for seven long years. I have fled in defeat and I have tasted victory and I will tell you which is sweeter. Despise me, then, for I have slain more of your kin than I can count, though I remember every single face. Collected here are the first three Gallow novels, along with a collection of framing short stories. THE FATEGUARD TRILOGY tells of the years when Gallow discovered that a man as notorious as he was cannot live a quiet life, and in the end must choose a side, even if that means betraying his own people. And when you betray a king, you accept that there will be a reckoning. The Fateguard are coming ... Contains THE CRIMSON SHIELD, COLD REDEMPTION and THE LAST BASTION

Release date: May 1, 2014

Publisher: Gollancz

Print pages: 1200

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Gallow: The Fateguard Trilogy eBook Collection

Nathan Hawke

Beside him Sarvic turned to run. A Vathan spear reached for him. Gallow chopped it away; and then he was slipping back and the whole line was

falling apart and the Vathen were pressing forward, pushed by the ranks behind them, stumbling over the bodies of the fallen.

For a moment the dead slowed them. Gallow turned and threw himself away from the Vathan shields. The earth under his feet was slick, ground to mud by the press of boots and watered with blood

and sweat. A spear point hit him in the back like a kick from a horse. He staggered and slipped but kept on running as fast as he could. If the blow had pierced his mail he’d find out soon

enough. The rest of the Marroc were scattering, fleeing down the back of the hill with the roars of the Vathen right behind. Javelots and stones rained around him but he didn’t look back.

Didn’t dare, not yet.

He slowed for a moment to tuck his axe into his belt and scoop up a discarded spear. The Vathen had horsemen and a man with a spear could face a horse; and when at last he did snatch a glance

over his shoulder, there they were, cresting the hill. They’d scythe through the fleeing Marroc and not one in ten would reach the safety of the trees because they were running in panic, not

turning to face their enemy as they should. He’d seen all this before. The Vathen were good with their horses.

Sarvic was pelting empty-handed down the hill ahead of him. They’d never met before today and had no reason to be friends, but they’d stood together in the wall of shields and

they’d both survived. Gallow caught him as the first Vathan rider drew back an arm to throw his javelot. He hurled himself at Sarvic’s legs, tumbling them both down the slope of the

hill. Gallow rolled away, turned and rose to a crouch behind his shield. Other men had dropped theirs as they ran but that was folly.

The javelot hit his shield and almost knocked him over. Another rider galloped towards them. At the last moment Gallow raised his spear. The Vathan saw it too late. The point caught him in the

belly and the other end wedged into the dirt and the rider flew out of his saddle, screaming, the spear driven right through him before the shaft snapped clean in two. Gallow wrenched the javelot

from his shield. He forced another into Sarvic’s hand. There were plenty to be had. ‘Running won’t help you.’

More Vathen poured over the hill. Another galloped past and hurled his javelot, rattling Gallow’s shield. Gallow searched around, wild-eyed and frantic for any shelter. Further down the

hill a knot of Marroc had held their nerve long enough to make a circle of spears. He raced towards them now, dragging Sarvic with him as the horsemen charged past. The shields opened to let him in

and closed around him. He was a part of it without even thinking.

‘Wall and spears!’ Valaric? A fierce hope came with having men beside him again, shields locked together, even if they were nothing but a handful.

Another wave of Vathan horse swarmed past. The Marroc crouched in their circle, spears out like a hedgehog, poking over their shields. The horsemen thundered on. There were easier prey to catch

but they threw their javelots anyway as they passed. The Marroc beside Gallow screamed and pitched forward.

‘You taught us this, Gallow, you Lhosir bastard,’ Valaric swore. ‘Curse these stunted hedge-born runts! Keep your shields high and your spears up and keep together, damn

you!’

The Vathan foot soldiers were charging now, roaring and whooping. As the last riders passed, the circle of Marroc broke and sprinted for the woods. The air was hot and thick. Sweat trickled into

Gallow’s eyes. The grass on the hill had been trampled flat and now gleamed bright in the sun. Bodies littered the ground close to the trees, scattered like armfuls of broken dolls where the

Vathan horse had caught the Marroc rout. Hundreds of them pinned to the earth with javelots sticking up from their backs. There were Lhosir bodies too among the Marroc. Valaric pointed at one and

laughed. ‘Not so invincible, eh?’

They reached the shadows of the wood and paused, gasping. Behind them the battlefield spread up the hill, dead men strewn in careless abandon. Crows already circled, waiting for the Vathen to

finish so they could get on with some looting of their own. The moans and cries of the dying mixed with the shouts and hurrahs of the victors. Before long the dead would be stripped bare and the

Vathen would move on.

‘Got to keep moving,’ Gallow said.

‘Shut your hole, forkbeard! They won’t follow us here.’ Valaric picked up his shield. He kicked a couple of Marroc who’d crouched against trees to catch their breath,

glared at Sarvic and headed off again at a run. ‘A pox on you!’ he said as Gallow fell in step beside him. ‘They’ll move right on to Fedderhun and quick. They don’t

care about us.’

But they still ran, a hard steady pace along whatever game trails they could find, putting as much distance as they could between them and the Vathen. Valaric only slowed when they ran out into

a meadow surrounded by trees and by then they must have been a couple of miles from the battle. Far enough. The Marroc were gasping and soaked in sweat but they weren’t dead. There

wouldn’t be many who’d stood in the shield wall on Lostring Hill who could say that.

The grass was up to their knees and filled with spring flowers and the air was alive with a heady scent. ‘Should be good enough,’ Valaric muttered. ‘We rest here for a bit

then.’ He threw a snarl at Gallow. ‘This is the end of us now, forkbeard. After here it’s each to his own way, and you’re not welcome any more.’

‘Will you go to Fedderhun, Valaric?’

Valaric snorted. ‘There’s no walls. What’s the point? Fedderhun’s a fishing town. The Vathen will either burn it or they won’t and nothing you or I can do will

change that. If your Lhosir prince wants a fight with the Vathen, I’ll be seeing to it that it’s not me and mine whose lives get crushed between you. I’ll be with my

family.’

There wasn’t much to say to that. Old wounds were best left be. Gallow’s own children weren’t so many miles away either. And Arda; and they’d be safe if the Vathen went

on to Fedderhun. He touched a hand to his chest and to the locket that hung on a chain around his neck, warm against his skin, buried beneath leather and mail. He could have been with them now, not

here in a wood and stinking of sweat and blood. ‘I’m one of you now,’ he said, as much to himself as to Valaric.

Valaric snorted. ‘You’re never that, forkbeard.’

Gallow set down his spear and his shield and took off his helm, letting the air dry the sweat from his skin. ‘It’s still your land, Valaric.’

But Valaric shook his head. ‘Not any more.’

‘Not any more.’ Valaric spat. Four hundred men. King Yurlak had sent four hundred forkbeards to fight ten thousand Vathen, and no one,

not even a crazy forkbeard, was that terrible. The fools on the hill were always going to break. He’d seen that from the moment he’d seen the Vathen and how many they were – and

it grated, thinking that if every man standing on the top of Lostring Hill this morning had been a Lhosir forkbeard then they just might have held the line, even outnumbered as they were, and maybe

it would have been the Vathen who’d broken and fled. Maybe. Because Yurlak hadn’t just sent four hundred men. He’d sent the Screambreaker, the Widowmaker, the Nightmare

of the North, and the Widowmaker had called the Marroc to arms and Valaric had been stupid enough to believe in him because a dozen years ago Valaric had been on the wrong end of the Widowmaker and

his forkbeards four times, one after the other, and each time the Marroc had had the numbers and Valaric had been certain that the Widowmaker couldn’t possibly win, and each time he had. A

man, he reckoned, ought to learn from a thing like that.

Out of the shadows of the trees a Vathan rider stepped into the clearing. Valaric froze for a moment but the rider was slumped in his saddle. He had blood all over him and he was clearly dead.

Half his face was missing.

‘Well, well. An unwanted horse. Now there’s a blessing.’ He grinned at the other Marroc around him. He’d picked them carefully, the ones who’d fight hard and long

and keep their wits. Torvic, the three Jonnics, Davic, all men who’d fought the forkbeards years ago and lived, even towards the end when the forkbeards had hired Vathan mercenaries with

their plundered gold and sent them in after the Marroc lines broke. The Marroc were used to running away by then, but not from horses. Thousands of men dead. And here he was not ten years later:

same forkbeards, same Vathen, only now the forkbeards claimed they were his friends. Valaric was having none of it.

The other Marroc were on their feet now. They were all thinking the same thing. All of them except the forkbeard Gallow, who’d keep quiet if he had any sense. Valaric got to the horse

first. He took the reins and hauled the dead Vathan out of the saddle.

‘So let’s see what we’ve got, lads.’ He left the body to the others and started going through the saddlebags. Food and water they’d share since none of them carried

any. A rare piece of good fortune. Someone else’s horse and saddle were fine things to carry away from a battle even after a victory. They’d have to divide it somehow. Needed a care

that did. He’d seen men kill each other over spoils like this, men who’d fought side by side only hours before.

‘There are more.’ Gallow was pointing off into the trees on the other side of the clearing.

Valaric growled. He let go of the horse and slipped his sword into his hand and picked up his shield where he’d left it in the grass. ‘Men? Or just horses?’

‘Horses.’

Horses was more like it. But still . . . He looked around the other Marroc. They all had a greedy look to them, but nervous too. ‘Right. You lot stay here. Keep on the edge of the trees.

Shields and spears ready in case. Me and the forkbeard, we’ll go see what’s there.’ He took a long hard look at Gallow. He was tall – certainly compared to a Marroc, and

maybe even tall among his own kind – and broad. His muscles might be hidden beneath mail and thick leather, but the man had been a soldier for years and worked in a forge before and after,

and there was no such thing as a weak-armed smith. His face was strong-boned and weathered. Valaric supposed there’d be some who’d say it was handsome if it hadn’t been for the

scar running across one cheek and the dent in his nose that went with it. He didn’t have the forked beard of a Lhosir any more, but Valaric’s eyes saw it anyway. Demon-beards.

Thick black hair that didn’t mark him as anything much one way or the other, but eyes of the palest blue like mountain glaciers. Lhosir eyes, cold and pitiless and deadly. Valaric cocked his

head. ‘You man for that?’

Gallow didn’t blink, just nodded, which made Valaric want to hit him. They stood face to face. Gallow looked down at him. Those ice-filled eyes were piercing, but Valaric

didn’t see the things he was looking for there. Forkbeards were merciless, filled with hate and rage – that’s how they’d been on the battlefield – but Gallow’s

eyes were just sad and weary. They had a longing to them.

‘You can go back to your own kind after this,’ he said shortly and brushed past on into the trees, eyes alert for the horses Gallow had seen. He picked up two of them straight away,

two more Vathan ones, riderless this time. Probably they’d followed the first. If there were more, so much the better.

‘I have a family, Valaric,’ said Gallow. ‘A wife and an old man and two young sons and a daughter. Those are my people now, and yes, I’ll go back to them. I don’t

know these Vathen but they’ll head west for Andhun. If that falls then who knows what they’ll do? Maybe they’re set on making new kings and cities and will leave my village alone.

Or maybe they’re the sort to swarm across the country with their horses and their swords, with burning torches, sweeping everything before them until nothing is left.’

‘Two young sons and a daughter, eh?’ Valaric couldn’t keep the bitterness out of his voice. ‘Sounds like you’ve been busy since you finished raping and murdering

and settled to the business of breaking our backs for the pleasure of your king.’

Gallow didn’t answer. Didn’t care, most likely, and the thought flashed through Valaric’s head to kill him right there and then while the two of them were alone. None of the

others would think any less of him for doing it. They’d all lost something when the forkbeards had come across the sea in their sharp-faced boats. He had no idea why Gallow had stayed.

Married a local girl, a smith’s daughter, and that alone was enough for Valaric to hate him. Our land, not yours. Nine years ago that was, when everyone had hated the forkbeards and

everything they stood for; but over those years the world had slowly changed. Everyone in these parts had come to hear of the forkbeard who hadn’t gone home. Maybe he even had friends now,

but for Valaric time had healed nothing. Gallow wasn’t welcome. None of them were.

‘There.’

Among the trees in the shade Valaric saw the shapes of more horses. A dozen maybe, one for each of them to ride and a few spare. Good coin if they could get to a place where they could sell

them. Changed things, that did. Not so much chance of a squabble over the spoils. The battle was going to give him a decent purse after all – which wasn’t why he’d come to fight

it, but a man still had to live.

Gallow pressed ahead through the trees to the horses, his hand staying close to his axe. He moved quickly but with cautious feet. Valaric let him go ahead while he tied up the first two animals

and then ran after him. Couldn’t let a forkbeard take the best of the pickings, but by then Gallow had stopped. When Valaric caught up, he saw why.

‘Modris!’ Cursing the old god’s name was the only thing left to do.

There were bodies everywhere. More horses too, a lot of them with their Vathan riders still slumped on their backs. The bodies on the ground were mostly forkbeards. Valaric took it all in and

nodded to the dead. He pointed through the trees, roughly back towards the battlefield. ‘Forkbeards were riding through the forest. The Vathen got ahead of them. They encircled them and took

your friends from the front and from behind.’

Gallow nodded. ‘The Lhosir made a stand rather than run. They dismounted because that’s how we like to fight. Like you, with our feet on the earth. The trees made that work for them.

No one ever thought of running. Not our way.’

‘The Vathen stayed in their saddles. Maybe that wasn’t so clever of them.’ There were a lot more dead Vathen than forkbeards. One of them had an arrow sticking out of his

chest. Valaric saw it and frowned: the forkbeards almost never used bows in battle. Arrows were for hunting or for cowards, but someone had used one here. For once not losing had mattered more than

how they fought.

‘They were protecting something,’ he whispered.

Gallow was staring around the corpses of his own people. He nodded. ‘These were the Screambreaker’s men.’ He walked slowly among them, axe drawn, eyes darting back and forth

among the shadows.

‘A pretty sight. Forkbeards and Vathen killing each other. My heart soars.’ Valaric didn’t feel it though, not here. He’d told himself that he and Gallow were enemies

from the moment they’d met, reminded himself that one day they might face each other in a different way, iron and steel edges drawn to the death. He hadn’t bothered much about that

though, because they both had to live through the Vathen first for that to ever happen, and Valaric had been in enough battles to know when victory lay with the enemy. The Marroc were mostly too

stupid and too fresh to fighting to see it, but the forkbeards must have known too, yet they’d faced the enemy anyway. They’d stood and held their shields and their spears and roared

their cries of battle. ‘Is he here then, your general?’

Gallow crouched beside a man with blood all over his face. He nodded. ‘Yes, Valaric, he is.’ He stood up. He still had his axe, and the way he was looking made Valaric wonder if that

day when they’d face each other wasn’t so far off after all. ‘He’s still alive.’ Gallow’s eyes were right for a forkbeard now. Merciless. Valaric took a step

back. He let his hand sit on the hilt of his own sword. The Nightmare of the North. The man who’d led the forkbeards back and forth across his land and stained it black with ash and red with

blood. Whoever killed the Widowmaker would be a hero among the Marroc, his name sung through the ages. And here he was, helpless, and there was only one forkbeard left standing in Valaric’s

way.

Gallow met his eye. ‘Now what?’

Valaric couldn’t draw his sword. Simply couldn’t. Not that Gallow scared him, although it would be a hard fight, that was for sure. Or he could have called the other Marroc and told

them what he’d found, because no forkbeard ever born was strong enough to face nine against one. But he didn’t do that either. The honest truth was that the Nightmare of the North

hadn’t done half the things people said he had. What he had done was stand with two thousand Marroc against the Vathen in a battle he must have known he couldn’t win.

He’d done that today. Valaric turned away. ‘They say things about you, Gallow.’

‘I’m sure they do.’

‘Tavern talk, now and then. They say you’re good to your word. That you work hard. Decent, they say, for a forkbeard. Always with the same words at the end: for a forkbeard.

Which is good. Doesn’t serve a man to forget who his enemies are. Why did you fight beside me and not with your own people, eh? Would have been safer, after all. Likely as not they were the

last to break.’ The words were bitter. Bloody forkbeards.

‘You’re my people now, Valaric.’

Valaric spat in disgust. ‘No, we’re not. A forkbeard is a forkbeard. Shaving your face changes nothing.’ He stared at Gallow and found he couldn’t meet the Lhosir’s

eyes any more. They were the eyes of a man who would stand without flinching against all nine of his Marroc if he had to because it would never occur to him to do anything else. Valaric shook his

head. ‘I tell you, I got so sick of running away from you lot. Must be a first for you.’

‘Selleuk’s Bridge, Marroc.’

‘Selleuk’s Bridge?’ Valaric bellowed out a laugh. ‘I missed that. Beat you good, eh?’

‘That you did.’ Gallow’s hand still rested on the head of his axe.

Valaric turned and started to walk away. ‘I’ve done my fighting for today. Best you be on your way. You take more than your share of these horses and we’ll come after you like

the howling hordes of hell. Go. And be quick about it.’

Gallow saw to the horses first. Two of them, one for him and one for the Screambreaker. That was fair. A man took what he needed and no more when

times were hard. He chose Lhosir mounts over the Vathan ones. Stamina over speed. He couldn’t see he’d be needing to win any races today but it was a long ride home and there

wouldn’t be any stopping while the sun was up.

He grimaced as he lifted the general across his shoulders. The Marroc called him the Widowmaker and the Nightmare of the North. To the Lhosir he was Corvin Screambreaker. He was a heavy man,

full of muscle, but old enough to have a belly as well, and nearly ten years of peace had done him no favours there. In his armour he was almost too much; but for all Gallow knew, the Screambreaker

was already knocking at the Maker-Devourer’s cauldron, and a Lhosir died in his armour if he could, dressed for battle with his spear in one hand and his shield in the other. That was a good

death, one the Maker-Devourer would add to his brew. Once Gallow had the Screambreaker on the back of his horse he strapped a shield to the old warrior’s arm and wrapped his limp fingers

around a knife and tied it fast with a leather thong ripped from a dead Vathan’s saddle. A sword would have been better, but swords were heavy. Chances were it would fall out and be lost and

then the Screambreaker would have nothing. A knife was at least something. The Maker-Devourer would understand that.

The Marroc were still back in the clearing. He ought to lay out the other Lhosir dead and speak them out, tell the Maker-Devourer of their names and their deeds, but he couldn’t. He

didn’t know them. He put swords and knives into empty hands, knowing full well that the Marroc would simply loot them again as soon as he was gone. With the Screambreaker’s horse

tethered to his own, he whispered a prayer to the sky and the earth, mounted and rode away.By the time he was free of the woods, the sun was sinking towards the distant mountains of the south.

Varyxhun was up there somewhere, up in the hills, surrounded by its mighty trees and guarding what had once been a pass through the mountains to Cimmer and the Holy Aulian Empire, but that was an

old path. Nothing but the odd shadewalker had come from the empire for more than fifty years now, while the castle overlooking Varyxhun itself was said to be haunted, full of the vengeful spirits

of the last Marroc to hold out against the Screambreaker. It was said to be the home of a sleeping water-dragon too, but the Vathen wouldn’t bother with it, dragon or not. They’d stay

north and move along the coast to Andhun. If Valaric and the other Marroc wanted a fight, that’s where it would be. I’ll be with my family, Valaric had said, but

Valaric’s family were six wooden grave markers in a field near a village by the coast, far away to the west, and had been for years. Everyone knew that.

He watched the sun finish creeping its way behind the distant horizon. As the stars came out, he stopped and eased Corvin to the ground and gently took away his shield. He let the horses cool

and took them to water; when he was done with that he searched their saddlebags for food for both of them and blankets for Corvin. The Screambreaker’s breathing was fast and shallow, but at

least he was still alive. Gallow forced one of his eyes open. It was rolled back so far that all Gallow could see was white. He made a fire, forced some water into the old man and ate from what

he’d found on the stolen horses.

‘If you die on me I’ll make a pyre if I can. I’ll miss a few things when I speak you out, I reckon. Forgive me. The sky knows there’s enough that I do know.’ He

took the Screambreaker’s hand and held it in his own. Talk to a troubled spirit. Helps it to remember who it is. Some witch had told him that, not long after he’d crossed the

sea. ‘They say you were a farmer once, no better than anyone else. The old ones who knew you before. Thanni Thunderhammer. Jyrdas One-Eye. Kaddaf the Roarer. Lanjis Halfborn. We listened to

all their stories. You were one of them, and you were their god too. Even then people knew you because of what you’d done, not because of a name you carried when you were born. “That a

man should somehow be better than his brothers simply because his father was rich? A Marroc nonsense. Lhosir will never stomach it.” You said that. Do you remember? I think we’d been

talking about Medrin.’ He let the Screambreaker’s hand go and poked at the fire. ‘Things were changing even before I crossed the sea. Some of these Marroc ideas were taking root

and a dozen and more winters have passed since then. Was it all different when you went back? Is that why you sailed again? Or was it simply too hard to resist? One last glorious stand. A battle

you couldn’t possibly win. A hero’s death for a hero’s life.’

He shifted the Screambreaker closer to the fire and settled down on the other side, gazing up at the stars. ‘We weren’t all that far from here when we last parted. Andhun opened its

gates to us, do you remember? You gave your word not to plunder it. We honoured that. By then we just wanted to go home, to get back across the sea and eat proper food again. Drink water that

tasted of mountain ice and marry some big-boned woman who’d bear us lots of sons and sleep in a longhouse with all our kin and not in those stinking Marroc huts. That sort of thing. We talked

about it all the time in those last weeks. Was it all there waiting for you just as we remembered it? It must have gone well enough for you and the others, what with bringing old Yurlak home and

every ship laden with loot and plunder. But I can’t say it’s been too bad here.’

The Screambreaker moaned and shifted, still wandering the Herenian Marches where the lost spirits of those neither alive nor dead were cursed to dwell, spirits like the Aulian shadewalkers.

Gallow patted his hand. ‘I wasn’t going to stay. I was as eager as the rest of you. But then Yurlak fell ill and everyone was sure he was going to die before you reached home and Medrin

would be king in his place. I’m not so fond of Medrin. So I got to thinking that maybe I’d stay and I watched you all go, ship by ship. You took Yurlak back across the sea so he could

die in his own house and among his own people, only then he went and didn’t die after all. If I’d still been in Andhun, I’d have come home when I heard but, as you see, I never

did. I left. Back to the mountains and the giant trees of Varyxhun. I was going to cross the Aulian Way. Go south, to lands we can hardly name, but on my way I found a forge and an old smith who

needed a strong arm to work it, and one of his three dead sons had left a wife behind him and a girl he likely never saw. It was us who left her a widow, us who took the old man’s sons, so I

won’t say they were happy with having a forkbeard around the place. But it felt good to be making things again. I wonder if you can understand that.’ He took a deep breath and touched

his hand to his chest, to the place where the locket lay next to his skin. ‘I took a lock of her hair while she was sleeping. A little luck to carry into battle. I know what you’d say

about that, old man. Laugh and scoff and tell me I was daft in the head, tell me that a man’s fate is written for him before he’s born. But here we are, so perhaps it worked, in its

way. No one would have her, see, because she was another man’s wife and she came with another man’s child to feed when both men and food were scarce, and she was . . . Screambreaker,

you’ll understand if you meet her. The Marroc prefer their women a little more docile.’ He rose and looked up at the stars. ‘A fine woman, Screambreaker. We have two sons of our

own now, and another daughter. You’ll like her if you last long enough to see her. Fierce and speaks her mind as often as she likes and doesn’t give a rat’s arse what anyone else

thinks. She won’t like you, sorry to say. Not one bit. Arda. That’s her name.’

He lay down beside the fire and pulled his cloak over himself. ‘Maker-Devourer watch over you, old man. Don’t get yourself lost in the Marches. And don’t tell Arda about the

hair. I’d never hear the end of it.’

Gallow closed his eyes. The Screambreaker was mumbling to himself. He hadn’t heard a word.

Gulsukh Ardshan’s horse shifted beneath him, impatient to move. From where he sat, the battlefield looked as though the Weeping God had

reached down from the sky and picked the Marroc legion up to the clouds, shaken them fiercely and let them go, scattering them to fall as they may. The light was fading but he still watched from

where the Marroc line had stood and looked down the gentle slope of the hillside. His riders swarmed over the dead, the dark litter of mangled shapes that had once been proud Marroc men. Looting

mostly, but it served a purpose. His horsemen needed their javelots, those that could be thrown again. There were spears and axes and shields and helms and perhaps even a few swords and pieces of

mail for the soldiers of the Weeping Giant, the ones who fought on foot. And, too, he was looking for someone.

In the failing light a dozen riders emerged from the trees at the bottom of the hill. Their horses looked tired, Gulsukh thought. They trotted closer up the slope and he saw that one of them had

a body slung over his saddle. Watching them weave their way in and out of the piles of naked corpses and the fires that were just being lit, he felt a hungry thrill of hope, but it died as they

approached. The lead horseman stopped in front of him, clenched his fist across his chest and bowed his head.

‘And what did you find, Krenda Bashar?’ Gulsukh peered at the body. A Lhosir, yes, but from a distance there was no telling who, other than it wasn’t the man he was looking

for.

The bashar kept his head bowed. He spoke loudly and quickly and a little too abruptly. ‘Ardshan! Beymar Bashar is dead. We followed his trail. He caught up with the Lhosir and tried to

take them but he was beaten. The men with him were killed. Most of the Lhosir too.’

‘B

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...