- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

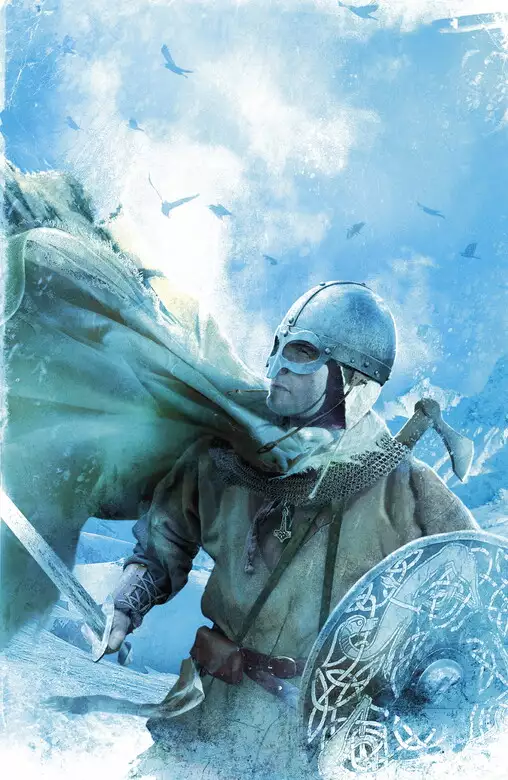

Synopsis

I fought against your people, and I have fought for them. I have killed, and I have murdered. I betrayed my kin and crippled my king. I led countless warriors to their deaths and fought to save one worthless life. I have stood against monsters and men and I cannot always tell the difference. Fate carried me away from your lands, from the woman and the family I love. Three hellish years but now, finally, I may return. I hope I will find them waiting for me. I hope they will remember me while all others forget. Let my own people believe me dead, lest they hunt me down. Let me return in the dark and in the shadows so no one will know. But hope is rare and fate is cruel. And if I have to, I will fight.

Release date: August 8, 2013

Publisher: Gollancz

Print pages: 287

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Gallow: Cold Redemption

Nathan Hawke

The man on the table in front of the Aulian was dying. The soldiers with their forked beards crowded around, full of anxious faces, but they knew

it. He was past help.

‘I’ll do what I can.’ The Aulian shook his head. ‘Leave him with me.’ When they did, that too was a sign of how little hope they had. A prince of the Lhosir left

alone with an Aulian wizard. The Aulian opened his satchel and bag and set about making his preparations.

‘Who are you?’ The dying man’s eyes were open. The skin of his face was grey and slick with sweat; but there was a fierce intelligence behind those eyes and a fear too. A

forkbeard prince who was afraid to die, but then who wouldn’t be when dying looked like this? The Aulian didn’t answer, but when he came close the Lhosir grabbed his sleeve. ‘I

asked you: who are you?’

‘I’m here to heal you. If it can be done.’

‘Can it?’

‘I will try, but I am . . . I am not sure that it can. If you have words to say, you should say them.’

The Lhosir let him go. He was trembling but he seemed to understand. The Aulian lifted his head and tipped three potions into his mouth, careful and gentle. ‘One for the pain. One for the

healing. One to keep you alive no matter what for two more days.’ Then he unrolled a cloth bundle and took out a knife and started to cut as gently as he could at the bandages over the

Lhosir’s wound. The room already stank of putrefaction. The rot was surely too far gone for the Lhosir to live.

‘I left him. I left my friend. I abandoned him.’

The Aulian nodded. He mumbled something as he cut, not really listening. The Lhosir was fevered already and the potions would quickly send him out of his mind. Soon nothing he said would mean

very much. ‘Even if you survive, your warring days are over. Even small exertions will leave you short of breath.’

‘I was afraid. I am Lhosir but I was afraid.’

‘Everyone is afraid.’ The Aulian lifted away a part of the bandage. The Lhosir flinched and whimpered where it stuck to the skin and the Aulian had to pull it free. The stench was

appalling. ‘I’m going to cut the wound and drain it now. This will hurt like fire even through the potions I’ve given you.’ The Aulian dropped the festering dressing into a

bowl of salt. As delicately as he could, he forced the Lhosir prince’s mouth open and pushed a piece of leather between his teeth. ‘Bite on this.’

The Lhosir spat it out. ‘The ironskins took him.’

The Aulian stopped, waiting now for the potions to take the Lhosir’s thoughts. ‘Ironskins?’

‘The Fateguard.’

The Aulian looked at the knife in his hand, razor sharp. ‘Then tell me about these iron-skinned men, Lhosir.’

So the Lhosir did, and the Aulian stood and listened and didn’t move, and a chill went through him. ‘There was another one like that,’ he said when the prince was done.

‘Long ago. We buried it far away from here under a place called Witches’ Reach. It was a terrible monster. Its power was very great, and very dangerous.’

The Lhosir started to talk about the friend he’d left behind, the one he said the ironskins had taken. The Aulian listened until the Lhosir’s words broke down into a senseless

mumble. The potions were taking hold. He turned his knife to the wound. The Lhosir screamed then. He screamed like a man having his soul torn out of him piece by piece. Like a man slowly cut in two

by a rust-edged saw. The Aulian worked quickly. The wound was deep and the rot had spread deeper still and the stink made him gag. He cut it out as best he could, drained the seeping pus away, cut

until blood flowed red and the screaming grew louder still. When he was done he tipped a handful of wriggling creatures onto the dying Lhosir’s bloody flesh and placed their bowl over the

wound.

The door flew open. Another Lhosir, with the dying prince’s bodyguards scurrying in his wake. They ran in and then stumbled and turned away, hit by the reeking air. The Aulian didn’t

look up. He wrapped cloth over the wound as fast as he could, hiding what he’d done. The first of the soldiers was on him quickly, gagging. The dying prince was quiet now. Fainted at

last.

‘Wizard, what have you done?’

The Aulian cleaned his knife and began to pack away his bags. ‘If he lives through the next two days he may recover. Send someone to me then.’ He looked at the forkbeard soldier.

‘Only if he lives.’

But the Lhosir wasn’t looking at him; he was staring at the hole in the dying prince’s side – at the blind thing wriggling from under the cloth. The Aulian frowned. He’d

been careless in his haste. He turned back to the soldier. ‘It will—’

‘Sorcerer!’ The forkbeard drove his sword through the Aulian. ‘Monster! What have you done?’

The Aulian tried to think of an answer, but all his thoughts were of another monster. The monster with the iron skin. And, as he fell to the floor and his eyes fixed on the dying Lhosir’s

hand hanging down from the table, how the Lhosir seemed to have too many fingers.

Addic stopped. He blew on his hands and rubbed them together and took a moment to look at the mountains behind him. Hard to decide which he liked

better: the ice-bitter clear skies of today or the blizzards that had come before. Wind and snow kept a man holed up in his hut with little to do but hope he could dig himself out again when it

stopped. A clear day like this meant working, a chance to gather wood and maybe even hunt, but Modris it was cold! He stamped his feet and blew on his fingers again. It wasn’t helping.

They’d gone numb a while back. His feet would follow before much longer. Cursed cold. He looked back the way he’d come, and it felt as though he’d been walking for hours but he

could still see the little jagged spur that overlooked the hut where he’d been hiding these last few days.

Up on the shoulder of the mountain beyond the spur a bright flash caught his eye, a momentary glimmer in the sun. He squinted and peered but it vanished as quickly as it had come and he

couldn’t make anything out. The snow, most likely, not that snow glinted like that; but what else could it be so deep in the pass?

Snow. Yes. Still, he kept looking now and then as he walked, until a wisp of cloud crossed the mountain and hid the shoulder where the old Aulian Way once ran from Varyxhun through the mountains

and out the other side. The Aulians had fallen long before Addic was born, but that didn’t mean that nothing ever came over the mountains any more. The winter cold was a killer, but

shadewalkers were already dead and so they came anyway.

He quickened his pace. The high road was carved into the mountainside over the knife-cut gorge of the Isset. It was hardly used at the best of times, even in summer when the snow briefly melted.

No one had come through since the blizzards, and so he was left to wade thigh-deep through the snow on a narrow road he couldn’t see along a slope that would happily pitch him over a cliff if

he took a wrong step. It was hard work, deadly tiring, but he didn’t have much choice now and at least the effort was keeping him warm. If he stopped to rest, he’d freeze. And it

probably hadn’t been another shadewalker high up in the mountains, but if it was then he certainly didn’t want to be the first living thing it found.

By the time he ran into the forkbeards, hours later, he’d forgotten the shadewalker. By then he was so tired that his mind was wandering freely. He kept thinking how, somewhere ahead of

him, one of the black lifeless trees that clung tenaciously to the gentler slopes above would have come down and blocked the road completely and he’d have to turn back, and he simply

didn’t have the strength to go all the way back to his safe little hole where the forkbeards would never find him.

And there they were: four of them, forkbeards armed to the elbows and riding hardy mountain ponies along the Aulian Way where they had no possible reason to be unless they’d finally caught

wind of where he was hiding; and the first thing he felt was an overwhelming relief that someone else had come this far and ploughed a path through the snow so that he wouldn’t have to, and

how that was going to make his walking so much quicker and easier for the rest of the way. Took a few moments more for some sense to kick in, to realise that this far out from Varyxhun the

forkbeards had come to hunt him down, winkle him out of wherever he was hiding and kill him. He might even have been flattered if he’d been carrying anything sharper than a big pile of animal

pelts over his shoulder.

The crushing weight of failure hit him then, the futility of even trying to escape; and then a backhand of despair for good measure, since if the forkbeards had learned where he was hiding then

someone must have told them, and there weren’t too many people that could be. Jonnic, perhaps. Brawlic, although it was hard to imagine. Achista? Little sister Achista?

His shoulders sagged. He tried to tell himself that no, she was too careful to be caught by any forkbeard, but the thought settled on him like a skin of heavy stone. He set the pelts carefully

down and bowed in the snow. The forkbeards seemed bored and irritable, looking for trouble. ‘My lords!’ They were about as far from lords as Addic could imagine, but he called them that

anyway in case it made a difference. Maybe they were out here on some other errand. He tried to imagine what that might be.

‘Addic.’ The forkbeard at the front beamed with pleasure, neatly murdering that little glimmer of hope. ‘Very kind of you to save us some bother.’ He swung himself down

from his pony, keeping a cautious distance. It crossed Addic’s mind then that although the forkbeards had horses, they were hardly going to take the High Road at a gallop in the middle of

winter when it was covered in snow, nor even at a fast trot unless they were unusually desperate to go over the edge and into the freezing Isset a hundred feet below. And if they knew him, then

there was only one reason for them to be out here. He turned and ran, or tried his best to, floundering away through the snow, not straight back down the road because that would make it

too easy for them but angling up among the trees. The snow shifted and slid under his feet, deep and soft. As he tried to catch his breath a spear whispered past his face.

‘Back here, Marroc. Take it like a man,’ bawled one of the forkbeards. Addic had no idea who they were. Just another band of Cithjan’s thugs out from Varyxhun. They probably

looked pretty stupid, all of them and him too, not that that was much comfort. Struggling and hauling themselves up through the steep slopes and the drifted snow, slipping and sliding and almost

falling with every other step, catching themselves now and then on the odd stunted tree that had somehow found a way to grow in this forsaken waste. The forkbeards were right behind him. Every

lurch forward was a gamble, a test of balance and luck, waiting to see what lay under the snow, whether it would hold or shift. Sooner or later one of them would fall and wouldn’t catch

himself, and then he’d be off straight down the slope, a quick bounce as he reached the road maybe and then over the edge, tumbling away among the rock and ice to the foaming waters of the

Isset. Which for Addic was no worse than being caught, but for the forkbeards it was probably a worse fate than letting him get away. Perhaps desperation gave him an advantage?

But no, of course it was him that slipped and felt his legs go out from under him. He rolled onto his back, sliding faster and faster through the snow, trying to dig in his feet and

achieving nothing. He could see the road below – with two more forkbeards standing on it right in his path – and then the great yawning abyss of the gorge. He threw out his arms and

clawed at the slope but the snow only laughed at him, coming away in great chunks to tumble around him, past him. He caught a glimpse of the forkbeards on the road looking up. Laughing, probably,

or maybe they were disappointed that the Isset and the mountainside were going to do their work for them. Maybe he could steer himself to hit them and they could all go over the edge together?

Two forkbeards on the road? He wondered for a moment where they’d come from, but then he caught a rock which sent him spinning and flipped him onto his front so he couldn’t

see where he was going any more. A tree flew past, bashing him on the hip; he snatched and got half a hand to it but his fingers wouldn’t hold. Then he hit the road. One foot plunged deep

into the snow and wrenched loose again with an ugly pain. His flailing hand caught hold of something and tried to cling on. The forkbeards, maybe? Again a moment of wonder, because he

could have sworn he’d only seen four forkbeards with their ponies and they’d all been chasing him, so these had to have come the other way, but that couldn’t be right . . .

A hand grabbed him, and then another. He spun round, tipped over onto his back again, felt his legs go over the edge of the gorge and into the nothing, but the rest of him stopped. The

forkbeards had caught him, and for one fleeting second he felt a surge of relief, though it quickly died: the forkbeards would have something far worse in mind than a quick death in the freezing

waters of the Isset.

A cloud of snow blew over him. When it passed he brushed his face clear so he could see. He was right on the edge of the gorge, the Isset grinning back up at him from far below. Two men stood

over him. They’d let go and they weren’t hitting him yet and so his first instinct was to get up and run, but getting back to his feet and avoiding slipping over the edge took long

enough for his eyes to see who’d saved him. He had no idea who they were or what they were doing out here on the Aulian Way in the middle of winter, but they weren’t forkbeards after

all.

The bigger of the two men held out a hand to steady him. They weren’t Marroc either. The big one, well, if you looked past the poorly shaven chin, everything about him said that he

was a forkbeard. Big strong arms, wide shoulders, tall and muscular with those pitiless glacier eyes. The other one though . . . Holy Modris, was he an Aulian, a real live one? He was

short and wiry, wasted and thin and utterly exhausted, but his skin was darker than any Marroc and his eyes were such a deep brown they were almost black. He was also bald. Their clothes

didn’t say much at all except that they were dressed for the mountains.

The four forkbeards were picking their way down from the slopes above, slow and cautious now. The two men who’d saved his life looked at him blankly. They were half dead. The

Aulian’s eyes were glassy, his hands limp and his breathing ragged. The big one wasn’t much better, swaying from side to side. Addic thought of the flash he’d seen from the

mountain shoulder hours ago and for a moment wonder got the better of fear. ‘You crossed the Aulian Way? In winter?’

The forkbeards were almost down now and they had their shields off their backs. The first one slid onto the road in a pile of snow about ten paces from where Addic was standing. He pulled out

his axe but didn’t come forward, not yet. He watched warily. ‘Hand over the Marroc.’

The big man stood a little straighter. ‘Why? What’s he done?’ He was breathing hard and his shoulders quickly slumped again. He looked ready to collapse. An ally,

maybe? But against four forkbeards? Addic glanced down the road, back the way he’d come.

‘Pissed me off,’ said the forkbeard with the axe. ‘Like you’re doing now.’

The stranger growled. The Aulian put a hand on his arm but the big man shook it off. ‘Three years,’ he snarled. ‘Three years I’m away and I come back to this.’ The

other forkbeards were on the road now, the four of them grouping together, ready to advance. The stranger drew his sword and for a moment Addic forgot about running and stared at the blade. It was

long, too long to be a Marroc edge – or a forkbeard one either – and in the winter sun it was tinged a deep red like dried blood. ‘Three years.’ The big man bared his teeth

and advanced. ‘Now tell me how far it is to Varyxhun and get out of my way!’

‘Three days,’ said Addic weakly, bemused by the idea of anyone telling four angry forkbeards to get out of my way. ‘Maybe four.’ The forkbeards were peering at

the stranger’s shield, an old battered round thing, painted red once before half the paint flaked off. It had seen a lot of use, that was obvious.

‘Move!’ The stranger walked straight at them.

‘Piss off!’

Addic didn’t see quite what happened next. One of the forkbeards must have tried something, or else the stranger just liked picking fights when he was outnumbered and exhausted. There was

a shout, a red blur and a scream and then one of the forkbeards dropped his shield and bright blood sprayed across the snow. It took Addic a moment to realise that the shield lying on the road

still had a hand and half an arm holding it.

‘Nioingr!’ The other three piled into the stranger. Addic wished he had a blade of his own, and if he had might have stayed. But he didn’t, and there wasn’t

anything he could do, and so he turned to flee and ran straight into the Aulian.

‘Hey!’

‘Out the way.’ He pushed past. The darkskin had a knife out but obviously didn’t know what to do with it. ‘If I were you, I’d run!’

The Aulian ignored him and took a step toward the fight. ‘Gallow!’

Addic heard the name as he fled. It stuck with him as he ran. He’d heard it somewhere before.

‘Gallow!’ The knife Oribas had was for stripping bark and carving wood, not for stabbing mad armoured men with forked beards, and even

if it had been, he wouldn’t have known how to use it.

The man Gallow had saved ran off down the road, back the way he’d come. Oribas watched him go. He ought to do the same – that would be sensible – but he didn’t. It would

be nice to think his decision had something to do with honour or loyalty or friendship but the truth was crueller: he simply didn’t have the strength. He could barely even stand, and that was

after Gallow had half carried him for the last two days through blizzards and snowfields deep enough to bury a man. Oribas couldn’t understand how Gallow was still on his feet, never mind

spoiling for a fight.

One of the forkbeards slammed Gallow with his shield and he stumbled. Oribas wanted to shout at them that it was hardly fair, taking on a man who’d just walked the Aulian Way in winter,

but instead he put his knife back where it belonged and sat in the middle of the road and closed his eyes. His legs had had enough. Besides, the forkbeards probably didn’t care about what was

fair, not after Gallow had chopped off their friend’s arm – he was lying in the snow, clutching his stump.

They were both as weak as children from crossing the pass but it still surprised Oribas when Gallow went down. A second forkbeard was out of the fight by then, sitting in the road rocking back

and forth, holding his guts. But then Oribas saw the red sword fall from Gallow’s hand and disappear into the soft snow at the big man’s feet. He saw Gallow stumble, one of the

forkbeards jab the butt of his axe into his face before he could find his balance again, and that was that. The forkbeard who’d knocked him down went to look at his comrade who was now lying

still in the road. He wrinkled his nose and prodded the body with his boot. ‘Fahred’s gone. Bled out.’

The other one still on his feet stamped through the snow to Oribas and picked him up by his shirt. ‘The Marroc! Where’d he go?’

Oribas pointed down the road.

‘And you didn’t stop him?’ The forkbeard snorted with contempt. ‘To the Isset with you then!’

He didn’t so much throw Oribas over the cliff as simply let go and push. Oribas stepped back to catch himself, screamed when his foot found only air and kept on going, and down he went,

spinning as he fell. The rest happened with blurring speed. For a moment he was looking towards the river far below, seeing that the cliff was actually more of a steep and jagged mess of stumps and

skeletal branches and sharp prongs of stone waiting to smash him to pieces. There was a dead tree sticking out below him that probably wouldn’t take his weight but he reached out a hand for

it anyway. His satchel slipped off his arm as he hit a boulder, flew down ahead of him and snagged on the tree, and then his fingers closed around the wood and his other arm was swinging around to

grasp the bark as well, and his shoulders felt like they were being torn out of their sockets . . .

The wood let out a horrible crack, shifted and shook him loose. Now he wasn’t falling as much as sliding, and a hundred fists punched him in the chest and the thighs as he spread-eagled

over the stones and scrabbled for purchase. His foot hit something solid, twisted him sideways and drove his knee up into his ribs, almost pitching him out into the void again. His fingers were

like the talons of an eagle, grabbing hold of whatever was there. And then he was still. By some miracle, he wasn’t falling any more.

For a time he stayed exactly there, gasping, arms and legs ablaze with the effort of it but not daring to let his grip go even a fraction. His lungs were burning. Waves of pain washed over him.

He tipped his head back and rolled his eyes as far as they’d go, looking up, half expecting to see the forkbeard who’d pushed him staring down, ready to drop rocks on him. But there was

nothing, only sky. He shifted, trying to get himself more comfortable, then levered himself up onto the ledge that had caught him. The road was about twenty feet above. The boulder that he’d

hit was half that. The dead tree would be a mere handspan beyond him if he got to his feet and stretched for it, but a handspan was still a handspan. His satchel hung off the end. It was all so

close but all desperately beyond him.

He hugged the ledge, listening, waiting for the forkbeards to see him when they finally threw Gallow’s corpse off the edge too, but they never did. He heard snatches of their talk for a

few minutes, taut and angry, but neither came to the side of the road, and then he heard them mount their ponies and move away. He supposed they must have gone, but he waited a while longer to be

certain. He had a good long look at the cliff above him. Gallow would have scaled it without a thought, like he was bounding up a flight of steps. Oribas summoned his courage and called out but got

no answer. Gallow was dead or unconscious or the forkbeards had taken him then. In his mind he saw the big man lying helpless in the snow, slowly bleeding out. He’d have to climb up by

himself. Ought to. Ought to right now. Get up onto the road and see what had happened but his arms and hands didn’t have the strength, his legs weren’t long enough.

He sat and wondered what to do, and after a time he felt the cold creeping in through his furs, making him dopey. He’d fall sooner or later. Even if he kept awake through to nightfall, the

cold would kill him before the next morning.

‘Hedge-born forkbeards!’ The shout came from close by on the road, probably loud enough to reach right through the valley. ‘Nioingr! All of you!’

If there was more, Oribas didn’t hear. By then he’d taken a lungful of cold air and was yelling as loud as he could, and he kept on until a face peered over the edge and stared at

him in wonder. It was the Marroc the forkbeards had been chasing.

‘You’re alive! What happened to your friend?’ The Marroc’s face was screwed up in confusion. ‘Do you need help?’

‘Yes.’

The man disappeared and came back a moment later. ‘Forkbeard whelps took all my furs,’ he said. He looked at Oribas expectantly.

‘Have you got any rope?’

The Marroc shook his head. ‘No.’

Gallow had been carrying both their packs, had been for days. ‘My friend had some,’ he said. ‘Is he still up there? They didn’t throw his body over the edge. If he is, he

has some.’ He closed his eyes and bit his lip.

The face disappeared and then came back for a second time. ‘No, no body up here. Plenty of blood over the snow, but that’s all. Someone got hurt bad. You sure they didn’t throw

him over?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then they must have taken him with them.’ The Marroc frowned. ‘Why would they do that?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Why do they do anything? Because they’re forkbeards. Why’d you help me?’

‘I didn’t.’ Oribas looked miserably away. ‘I just stood and watched. As for Gallow? I don’t know. It’s what he does but I never understood

why.’

The Marroc peered closer. ‘Gallow? That his name?’

‘Yes.’

‘Funny. They were looking for a Gallow in these parts a few years back. Is he one of them? A forkbeard?’

‘A Lhosir. Yes.’ Oribas felt his heart sinking. Neither of them had any rope. This man was going to leave him here because there was nothing else he could do. The cold was chilling

him deep now. His fingers and his feet were numb. He could feel himself slowly shutting down.

Another pause. ‘Are you an Aulian?’

‘I suppose, if that means anything any more. Look, there are some trees on the slope above the road. You could cut some strips of bark and make a rope with those if you haven’t got

any.’ His hands were turning stiff even stuffed down inside his furs. His legs were going too, not from the cold but just from having nothing left to give after the bitterness of the

mountains.

‘I don’t know about that. Actually, I reckon you can just climb up from there unless your arms and legs are broken.’

‘No, I can’t.’

‘Yes, you can. It’s not even that hard.’

Oribas shook his head and turned away. ‘I barely have the strength to stand, my friend.’

The next thing he knew, snow was falling around him and the Marroc was climbing down. He made it look easy. A moment later he stood beside Oribas on the ledge. ‘See. Stand up.’

‘I don’t think I can.’

‘Then how were you going to climb a rope?’

Oribas shrugged forlornly. The Marroc shoved him sideways, almost tipping him off into the river. Oribas swore. ‘Are you mad?’

But for a moment he’d forgotten how tired he was. The Marroc nodded. ‘Better. Now how about you either stand up or I push you off this ledge and into the river. Either your legs get

you up there or I do you a mercy.’

It was the sort of thing Gallow would have done and it made Oribas feel pathetic and stupid. The Marroc coaxed and cajoled and threatened him until he wrapped his arms around the Marroc’s

neck and his legs around the man’s waist, and then th. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...