Remember the big moment in The Wizard of Oz movie when Dorothy says, “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore?” Boy, could I relate. Only a twister hadn’t brought me here; a promise had. This wasn’t the Emerald City, but the Emerald Coast of Florida. Ruby slippers wouldn’t get me home to Chicago. And neither would my red, vintage Volkswagen Beetle, if anyone believed the story I’d spread around. Nothing like lying to people you’d just met. But it couldn’t be helped. Really, it couldn’t.

The truth was, as a twenty-eight-year-old children’s librarian, I never imagined I’d end up working in a beach bar in Emerald Cove, Florida. In the week I’d been here I’d already learned toddlers and drunk people weren’t that different. Both were unsteady on their feet, prone to temper tantrums one minute and sloppy hugs the next, and they liked to take naps wherever they happened to be. Go figure. But knowing that wasn’t helping me right now. I was currently giving the side-eye to one of the regulars.

“Joaquín, why the heck is Elwell wearing that armadillo on his head?” I asked in a low voice. Elwell Pugh sat at the end of the bar, his back to the beach, nursing a beer in his wrinkled hands. I had known life would be different in the Panhandle of Florida, but armadillo shells on people’s heads?—that was a real conversation starter.

“It’s not like it’s alive, Chloe,” Joaquín Diaz answered, as if that made sense of a man wearing a hollowed-out armadillo shell as a hat. Joaquín raised two perfectly manicured eyebrows at me.

What? Maybe it was some kind of lodge thing down here. My uncle had been a member of a lodge in Chicago complete with funny fez hats, parades, and clowns riding miniature motorcycles. But he usually didn’t sit in bars in his hat—at least not alone.

Elwell sported the deep tan of a Florida native. A few faded tattoos sprinkled his arms. His gray hair, cropped short, and grizzled face made him look unhappy—maybe he was. I’d met Elwell when I started working at the Sea Glass. I already knew that Elwell was a great tipper, didn’t make off-color comments, and kept his hands to himself. That alone made him a saint among men to me, because all three were rare when waitressing in a bar. At least in this one, the only bar I’d ever worked in.

It hadn’t taken me long to figure out Elwell’s good points. But I’d seen more than one tourist start to walk in off the beach, spot him, and leave. There were other bars farther down the beach, plenty of places to drink. So, Elwell and his armadillo hat seemed like a problem to me.

“Elwell started wearing it a few weeks back,” Joaquín said with a shrug that indicated what are you going to do about it. Joaquín’s eyes were almost the same color as the aquamarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico, which sparkled across the wide expanse of beach in front of the Sea Glass. With his tousled dark hair, Joaquín looked way more like a Hollywood heartthrob than a fisherman by morning, bartender by afternoon. That combination had the women who stopped in here swooning. He looked like he was a few years older than me.

“It keeps the gub’ment from tracking me,” Elwell said in a drawl that dragged “guh-buh-men-t” into four syllables.

Apparently, Elwell had exceptional hearing, or the armadillo shell was some kind of echo chamber.

“Some fools,” Elwell continued, “believe tinfoil will stop the gub’ment, but they don’t understand radio waves.”

Great, a science lesson from a man with an armadillo on his head. I nodded, keeping a straight face because I didn’t want to anger a man who seemed a tad crazy. He watched me for a moment and went back to staring at his beer. I grinned at Joaquín and he smiled at me. Joaquín didn’t seem concerned, so maybe I shouldn’t be either. I glanced at Elwell again. His eyes always had a calculating look that made me think there was a purpose for the armadillo shell that had nothing to do with the “gub’ment,” but what did I know?

“Whatta ya gotta do to get a drink round here?” a man yelled from the front of the bar. He was one of two men playing a game of rummy at a high top. They were in here almost every day.

“Not shout for a drink, Buford,” Joaquín yelled back. “Or get your lazy as—” he caught himself as he glanced at Vivi, the owner and our boss, who frowned at him from across the room, “asteroid up here.”

Vivi’s face relaxed into a smile. She would have made a good children’s librarian considering how she tried to keep things PG around here. Joaquín tilted his head toward me. I took a pad out of the little black apron wrapped around my waist and trotted over to Buford.

“Would you like another Bud?” I asked Buford. “Or something else?”

“Sure would,” Buford said. There was a “duh” note in his voice suggesting why else would he be yelling to Joaquín.

“Another Maker’s Mark whiskey?” I looked at Buford’s card playing partner as I wrote his beer order on my pad.

“You have a good memory,” he said looking at his half empty glass. “But I’m good.”

Good grief, I’d been serving him the same drink all week, I’d hoped I could remember his order. I made the rounds of the other tables. By each drink I wrote a brief description of who ordered it: beer, black hair rummy player; martini, dirty, yellow Hawaiian shirt; gin and tonic, needs a bigger bikini. I’d seen way more oiled-up, sweaty, sandy body parts than I cared to in the week I’d been here. Not even my dad, a retired plumber, had seen this many cracks at a meeting of the Chicago plumbers union.

Those images kept haunting my dreams, along with giant beach balls knocking me down, talking dolphins, and tidal waves. I’d yet to figure out what any of them meant—well, maybe I’d figured out one of them. But I wasn’t going to think about that now.

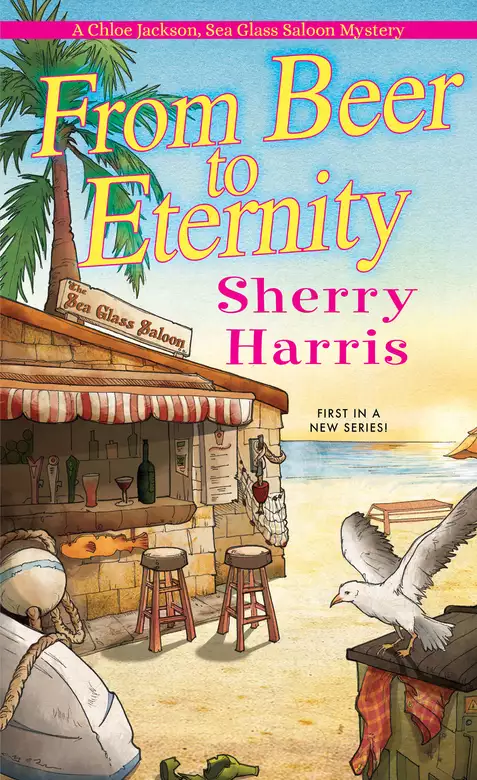

Nope, I preferred to focus on the scenery, because, boy, this place had atmosphere—and that didn’t even include Elwell and his armadillo shell hat. The Sea Glass Saloon I’d pictured before I’d arrived had swinging, saloon-style doors, bawdy dancing girls, and wagon-wheel chandeliers. This was more like a tiki hut than an old western saloon, though thankfully I didn’t have to wear a sarong and coconut bra top. I could fill one out, but I preferred comfortable tank tops. Besides, the Gulf of Mexico was the real star of the show. The whole front of the bar was open to it, with retractable glass doors leading to a covered deck.

The Sea Glass catered to locals who needed a break from the masses of tourists who descended on Emerald Cove and Destin, the bigger town next door, every summer. Not that Vivi would turn down tourists’ money. She needed their money to stay open, as far as I could tell.

Like Dorothy, I was up for a new adventure and finding my way in a place that was so totally different from my life in Chicago. I only hoped that I’d find my own versions of Dorothy’s Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion to help me on the way. So far, the only friend I’d made—and I wasn’t too sure about that—was Joaquín. He, and everybody, seemed nice enough, but I was still trying to adjust to the relaxed Southern attitude that prevailed among the locals in the Panhandle of Florida. It was also called the Emerald Coast, LA—lower Alabama, and get this—the Redneck Riviera.

You could have knocked me over with a palm frond when I heard that nickname. The chamber of commerce never used it, nor would you see the name in a TV ad. But the locals used it with a mixture of pride and disdain. Some wanted to brush it under the proverbial rug, while others embraced it in its modern-day form—people who were proud of their local roots.

The Emerald Coast stretched from Panama City, Florida, fifty miles east of here, to Pensacola, Florida, fifty miles to the west. The rhythm and flow was such a contrast from the go, go, go lifestyle in Chicago, where I’d lived my entire life. The local attitude matched the blue-green waves of the Gulf of Mexico, which lapped gently on sand so white you’d think Mr. Clean came by every night to tidy up.

As I walked back to the bar Joaquín’s hips swayed to the island music playing over an old speaker system. He was in perpetual motion, with his hips moving like some suave combination of Elvis and Ricky Martin. My hips didn’t move like that even on my best day—even if I’d had a couple of drinks. Joaquín glanced at me as he added gin, tonic, and lime to a rocks glass. I’d learned that term a couple of days ago. Bars had names for everything, and “the short glasses” didn’t cut it in the eyes of my boss, Vivi Jo Slidell. And yeah, she was as Southern as her name sounded. I watched with interest as Joaquín grabbed a cocktail shaker, adding gin, dry vermouth, and olive brine.

“Want to do the honors?” Joaquín asked, holding up the cocktail shaker.

I glanced at the row of women sitting at the bar, one almost drooling over Joaquín. One had winked at him so much it looked like she had an eye twitch, and one was now looking at me with an openly hostile expression. Far be it from me to deprive anyone from watching Joaquín’s hips while he shook the cocktail.

“You go ahead,” I said with a grin and a small tilt of my head toward his audience. The hostile woman started smiling again. “Have you ever thought about dancing professionally?”

“Been there, danced that,” Joaquín answered.

“Really?” the winker asked.

“Oh, honey, I shook my bootie with Beyoncé, Ricky Martin, and Justin Timberlake among others when I was a backup dancer.”

“What are you doing here, then?” I was astonished.

“My husband and I didn’t like being apart.” Joaquín started shaking the cocktail, but threw in some extra moves, finishing with a twirl. “Besides, I get to be outside way more than I did when I was living out in LA. There, I was always stuck under hot lights on a soundstage. Here, it’s a hot sun out on the ocean. Much better.” He winked at the winker, and she blushed.

The women had looked disappointed when he mentioned his husband, but that explained Joaquín’s immunity to the women who threw themselves at him. He didn’t wear a ring, but maybe as a fisherman it was a danger. My father didn’t wear one because of his plumbing, but he couldn’t be more devoted to my mom.

“Put three olives on a pick, please,” Joaquín asked. While he finished his thing with the shaker, I grabbed one of the picks—not the kind for guitars; these were little sticks with sharp points on one end—fancy plastic toothpicks really. Ours were pink, topped with a little flamingo, and I strung the olives on as Joaquín strained the drink into a martini glass.

“One dirty martini,” Joaquín said with a hand flourish.

I popped open a beer and poured it into a glass, holding the glass at an angle so the beer had only a skiff of foam on the top. It was a skill I was proud of because my father had taught me when I was fourteen. Other fathers taught their daughters how to play chess. My friends knew the difference between a king and a rook. Mine made sure I knew the importance of low foam. You can guess which skill was more popular at frat parties in college.

As I distributed the drinks, I thought about Boone Slidell, my best friend since my first day of college. The promise that brought me here? I’d made it to him one night at the Italian Village’s bar in downtown Chicago. We’d had so much fun that night, acting silly before his deployment to Afghanistan with the National Guard. But later that night he’d asked me, should anything happen to him on his deployment, would I come help his grandmother, Vivi. He had a caveat. I couldn’t tell her he’d asked me to.

“Yes,” I’d said. “Of course.” We’d toasted with shots of tequila and laughter, never dreaming nine months later that my best friend in the world would be gone. Twenty-eight years old and gone. I’d gotten a leave of absence from my job as a children’s librarian and had come for the memorial service, planning to stay for as long as Boone’s grandmother needed me. But Vivi wasn’t the bent-over, pathetic figure I’d been expecting to save. In fact, she was glaring at me now from across the room, making it perfectly clear that she neither needed nor wanted my help. I smiled at her as I went back behind the bar.

Vivi was a beautiful woman with thick silver hair and a gym-perfect body. Seventy had never looked so good. She wore gold, strappy wedge sandals that made my feet ache just looking at them, cropped white skinny jeans, and an off-the-shoulder, gauzy aqua top. I always felt a little messy when I was with her.

“A promise made is a promise kept.” I could hear my dad’s voice in my head as clear as if he were standing next to me. It was what kept me rooted here, even with Vivi’s dismissive attitude. I’d win her over sooner or later. Few hadn’t eventually succumbed to my winning personality or my big brown eyes. Eyes that various men had described as liquid chocolate, doelike, and one jerk who said they looked like mud pies after I turned him down for a date.

In my dreams, everyone succumbed to my personality. Reality was such a different story. Some people apparently thought I was an acquired taste. Kind of like ouzo, an anise-flavored aperitif from Greece, that Boone used to drink sometimes. I smiled at the memory.

“What are you grinning about?” Joaquín asked. Today he wore a neon-green Hawaiian shirt with a hot-pink hibiscus print.

“Nothing.” I couldn’t admit it was the thought of people succumbing to me. “Am I supposed to be wearing Hawaiian shirts to work?” I asked. He wore one every day. I’d been wearing T-shirts and shorts. No one had mentioned a dress code.

“You can wear whatever your little heart desires, as long as you don’t flash too much skin. Vivi wouldn’t like that.” He glanced over my blue tank top and shorts.

“But you wear Hawaiian shirts every day,” I said.

“Honey, you can’t put a peacock in beige.”

I laughed and started cutting the lemons and limes we used as garnishes. The juice from both managed to find the tiniest cut and burn in my fingers. But Vivi—don’t dare put a “Miss” in front of “Vivi,” despite the tradition here in the South—wasn’t going to chase me away by assigning me all the menial tasks, including cleaning the toilets, mopping the floors, and cutting the fruit. I was made of tougher stuff than that and had been since I was ten. To paraphrase the Blues Brothers movie, I was “on a mission from” Boone.

“What’d those poor little limes ever do to you?”

I looked up. Joaquín stood next to me with a garbage bag in his hand and a devilish grin on his face. He’d been a bright spot in a somber time. He smiled at me and headed out the back door of the bar.

“You’re cheating,” Buford yelled from his table near the retractable doors. He leaped up, knocking over his chair just as Vivi passed behind him. The chair bounced into Vivi, she teetered on her heels and then slammed to the ground, her head barely missing the concrete floor. The Sea Glass wasn’t exactly fancy.

Oh, no. Maybe incidents like this were why Boone thought I needed to be here. Why Vivi needed help. The man didn’t notice Vivi, still on the floor. Probably didn’t even realize he’d done it. Everyone else froze, while Buford grabbed the man across from him by the collar and dragged him out of his chair knocking cards off the table as he did.

I put down the knife and hustled around the bar. “Buford. You stop that right now.” I used the firm voice I occasionally had to use at the library. Vivi wouldn’t allow any gambling in here. Up to this point there hadn’t been any trouble.

Buford let go of his friend. I kept steaming toward him. “You knocked over Vivi.” I lowered my voice, a technique I’d learned as a librarian to diffuse situations. “Now, help her up and apologize.”

He looked down at me, his face red. I jammed my hands on my hips and lifted my chin. He was a good foot taller than me and outweighed me by at least one hundred pounds. I stood my ground. That would teach him to mess with a children’s librarian, even one on a leave of absence. I’d dealt with tougher guys than him. Okay, they had been five years old, but it still counted.

He turned to Vivi and helped her up. “I’m sorry, Vivi. How about I buy a round for the house?”

Oh, thank heavens. For a minute there, I thought he was going to punch me. Vivi looked down at her palms, red from where they’d broken her fall. “Okay. But you pull something like that again and you’re banned for life.”

I expected a thanks from Vivi—that wasn’t asking too much, right?—but she swept by me to the back, and I heard her office door close. Soundly. Winning her over, figuring her out for that matter, wasn’t going to be easy. Joaquín had returned and looked at me, eyes wide. I took more orders and he started mixing drinks—not that there were that many people in here midafternoon. I was more of a beer and wine drinker, so I’d only made a couple of cocktails since I’d started here. And always under Joaquín’s watchful eye, so I stood aside again today. Because the drinks were on Buford’s tab, everyone had ordered expensive gins, bourbons, and rums. Buford complained loudly about that, but everyone ignored him.

I probably wasn’t the best person to work in a bar because the smell of whiskey nauseated me. That was thanks to a bad experience in high school instigated by my two older brothers, who thought they were hilarious. They weren’t. Instead of thinking about that,

I focused on Joaquín’s strong hands. They were a blur of motion as he fixed the drinks. In no time, everyone was back in their seats, most facing the ocean. Except for the women at the bar, who continued to flirt with Joaquín. And Elwell, who nursed his beer.

Fans whirled and wobbled above, causing the warm ocean breeze to mingle with the arctic air blasting from air conditioners in the back of the bar. The resulting mix made it quite pleasant in here. I added lemons, limes, or cherries to garnish the drinks, as instructed by Joaquín.

“Good work, by the way,” he said.

“I just stood out of your way and watched.” Being praised for adding fruit to drinks was demoralizing after finishing college, getting a master’s degree in library science, and working in the library full-time.

“I meant with Buford.” Joaquín pointed at the man who’d knocked over Vivi.

“Vivi didn’t seem to think so.”

Joaquín turned his beautiful eyes to me. “She doesn’t like to think she needs help. If she could run this place by herself, she would. But deep down, she’s gratef. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved