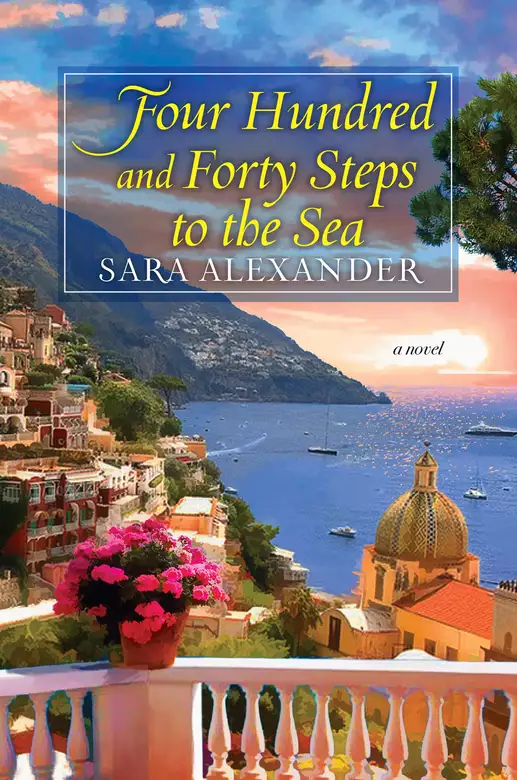

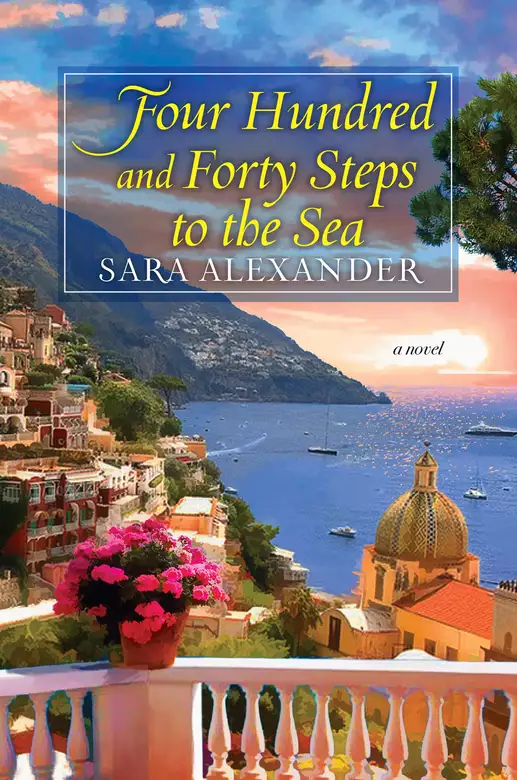

Four Hundred and Forty Steps to the Sea

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In a richly romantic novel set in stunning Positano, Italy, Sara Alexander weaves a story of love, family loyalty, and sacrifice spanning five decades ...

Nestled into the cliffs in southern Italy's Amalfi coast, Positano is an artist's vision, with rows of brightly hued houses perched above the sea and picturesque staircases meandering up and down the hillside. Santina, still a striking woman despite old age and the illness that saps her last strength, is spending her final days at her home, Villa San Vito. The magnificent eighteenth-century palazzo is very different from the tiny house in which she grew up. And as she decides its fate, she must confront the choices that led her here so long ago.

In 1949, Positano is as yet undiscovered by tourists, a beautiful, secluded village shaking off the dust of war. Hoping to escape poverty, young Santina takes domestic work in London, ultimately becoming a housekeeper to a distinguished British major and his creative, impulsive wife, Adeline. When they move to Positano, Santina returns with them, raising their daughter as Adeline's mental health declines. With each passing year, Santina becomes more deeply enmeshed within the family, trying to navigate her complicated feelings for a man who is much more than an employer—while hiding secrets that could shatter the only home she knows.

Release date: August 28, 2018

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Four Hundred and Forty Steps to the Sea

Sara Alexander

Those mountain forests were my home. My mother was a goat; she leaped from stone to stone, fearless, focused, and precise. I never once saw her slip, neither lose balance nor plant any seed of fear into my brother nor I. We followed her lead, limber and lithe, racing against one another to see who might discover the most. My brother and I were cradled by the scent of damp moss since I can remember. That deep green underfoot carpeted our adventures. We took the view of our dramatic coastline for granted. From up here on our hills, we could see the lower mountains sharpen up and out of the cove of Positano with its viridian water. The tiny Sirenuse islands floated just beyond, haunted by those heartless sirens luring ancient Greek adventurers to their watery deaths. Farther in the distance lay Capri, a tiny mound rising up from the water, like the scale of an underwater dragon.

Sometimes we would pass an intrepid party of travelers walking our narrow Path of the Gods, stopping to admire the view as the mountain range snaked into the hazy distance toward the Bay of Naples. Sometimes we might come across them sat upon the occasional grass clearing, a light picnic laid before them. The salty smell of prosciutto and fresh bread made our mouths water. Mother would mutter through gritted teeth to not stare like stray dogs.

We dodged the sharp crags that jutted through the living forest floor, competing to see who could be the fastest. Mother would let us stop and drink the icy mountain water as it cascaded down toward the coast. While we knelt, numbing our hands and washing our faces, she taught us which mushrooms would kill us—I can’t shake the feeling that it was her peculiar way of imparting self-defense. Perhaps one day a venomous fungus would save me from a predator after all? Up in the Amalfi mountains, the danger lurking in the dark was tangible to us hill folk. Its name was Hunger.

My father drank most of what we earned. I helped Ma with her laundry runs, watching her knuckles callus against the stone washer troughs in town. After the washing was done and delivered, we would climb over a thousand steps back up from the fishing town of Positano to Nocelle, weaving our cobbled journey through Amalfitani woods toward the small fraction nestled in the hilly periphery, and from there begin our scramble to our tiny house. Arriving home we’d either find my brother huddled in a corner by a dying fire with my father nowhere to be seen, or the latter tight with drink. I knew I would be damned for thinking it, but I hated that man. I hated the scars he left my mother with. The heavy hand my brother and I were dealt for the smallest trifle, but most of all the way my courageous mother, who spoke her mind to all the gossips by the well, who was first to put any man in his place who so much as dared look at her, was reduced to a quiver when my father was in one of his thunders. I ought to have brewed a fatal fungo broth for him and be done with it. Too late now.

That Tuesday—Martedi—the sky was full of rancor, like the planet Mars it’s named after. The wind whipped from the sea and blew in a thick fog. Within minutes my mother was a gray silhouette. She slowed her pace a little, ahead of me. My shoes scuffed the damp boulders, dew seeping in through the tiny holes on the worn sole. Several times I lost my footing. Mother called back to us, “Santina! Marco! Stay where you are! It’s not safe today—we’ll turn back.” We stopped, my little brother, Marco, a few paces behind me. I heard her footsteps approach, tip-tapping with familiar confidence. Then there was a ricochet of small rocks. A cry. Marco and I froze to the sound of more rocks tumbling just beyond where I could see. We called out. I heard my mother call back to us.

The silence that followed drained the blood from my face. My heart pounded. I called again. Marco started to cry. I couldn’t hear my mother answer beyond his wails. I screamed at him to stop, but it just made him worse. I had little strength to stifle my panic. My brother took a step toward me. He slipped and fell, hitting his elbow hard on the sharp edge of a rock. His blood oozed crimson onto the moss. I yanked him up and wrapped my headscarf around his elbow. “We’ll go home now,” I began, trying to swallow my hot tears of terror. “I’ll come back for Mamma when the sun is out, sì?” He nodded back at me, both of us choosing to believe my promise, fat tears rolling down his little cheeks.

We never saw our mother again.

Father’s mourning consisted more of fretting about what to do with the incumbent children he had to feed than grieving the loss of the fine woman who had fallen to her death. One day he declared that I was to go and live down by the shore in Positano with Signora Cavaldi, the widow now running her late husband’s produce store. In return for lodging and food, I was to assist her. I felt torn; delirious with the prospect of escape from the misery of life on the mountainside with this man for a father, and terror at what life would now entail for Marco. The next day, an uncle from Nocelle climbed up to speak with my father. Marco would be needed to tend to his farm. The deal was sealed. We were dispatched to new parents. I try to forget the expression on Marco’s face as he was led away from me. He walked downhill, his reluctant hand in my uncle’s, ripping a piece out of me with each step. I patched over the gaping hole and the fresh wound of my mother’s death, with brittle bravado. My father would not see me cry. I wished that would have been the last time I ever saw him too.

Signora Cavaldi’s shop was a cavern carved into the stubborn rock that enveloped the cove of Positano. She held a prime position between the mill and the laundry, minimizing competition. I now wonder whether that had more to do with her careful management of the town’s politics and politicians or her not so secret connection with the men who protected the trade and tradesmen. I wouldn’t like to guess whom she paid nor how much, or indeed how much others paid her, but my instinct tells me her tentacles stretched far and wide. I arrived wearing the only dress I owned, a smock of doleful gray, which matched my mood. She gave me the once-over and pieced together an opinion as deft as she would calculate someone’s shopping bill. The woman was a wizard with numbers, that took me no time to figure out, but she loathed children.

“You’re twelve now, Santina, sì?”

“Sì, Signora,” I answered, trying to stop my left leg from shaking. It was an embarrassing habit since I had succumbed to polio as a younger child, and my withered calf always revealed too much about what I was feeling at any given time.

“You’re here to work, yes? I’ll give you two days to learn what we do, and I expect to never repeat myself, capisci?”

“Sì, I understand, Signora.”

She set me to work immediately, sorting the produce, laying out chestnuts in baskets, polishing the scales that grew dirty again with the weighing of earth-dusted mushrooms. I cleaned the vats of oil, swept and scrubbed the floor. As the sun dipped, she called out for me to light the stove in the kitchen of the apartment upstairs and brew a broth for dinner. At first it struck me as a little out of my remit—I had been told that I would be served food in return for working, and I will admit the idea of having regular meals was exhilarating. However, my own cooking skills were not well honed—Mother and I permitted ourselves a full meal maybe once a week, and meat was scarce. I stood, hesitant, before the stove, in a strange kitchen not knowing where anything might be kept. I was loath to search amongst her things. I went downstairs. She scolded me for lacking initiative: “Look around you, mountain girl! We have a shop, the best grocers in the town. I have a clean kitchen, which you will keep pristine, and I want, thanks be to God, for very little. Don’t let me see you down here until dinner is served.” And with that she turned back toward the broccoli rabe, placing them in neat lines inside wooden crates ready for the following day.

I fought with several pans, finely chopped as many of the vegetables I could find that would not be good for selling the following day, dropped in a fist of barley, lentils, and parsley, and, eventually, there was a broth that would fill our stomachs. A little thin perhaps, and lacking in salt, as Signora Cavaldi was so quick to point out, but it was hot and reminded me that I was not on the mountains any longer.

I slept in a thin cot placed in the short hallway between Signora’s room and her son, Paolino’s, room. It was drafty but nothing like the limp damp of our stone mountain hut. I didn’t hear my father’s drunken snores—that was a degree toward comfort. Nor could I hear the soft breath of my mother, or feel Marco’s fidgety feet scrambling against mine through his dreams. Silent tears trickled down my face. I felt the droplets inside my ears. I let the wetness dry there, hoping my prayers and love would reach Marco up in Nocelle, a thin line of golden thread. After a time I must have given in to sleep because the next thing I remember is Cavaldi blowing down her nose at me with strips of sun fighting into the hallway from her room.

The days merged into one, each as laborious as the one before. I was sent on deliveries, some as heavy as would warrant a porter and his donkey, but Cavaldi would not hear of it; if I had been sent down for her to look after, then it was my duty to earn my keep. I built quite a reputation amongst the porters in town, who ferried supplies up and down the steep alleys around the village. They called me Kid, alluding to my climbing skills as well as my age. It made me think of my mother. I was growing, at long last, and I noticed my muscles becoming more defined and strong. Sometimes the young boys would laugh at me for doing men’s jobs. The local women were not so kind. The Positanese knew mountain people when they saw them. We had the outside about us, the air of the wild, a fearlessness which I’m sure was disconcerting. We lived closer to death than they.

When I turned sixteen, Paolino, who till then had paid me as much attention and courtesy as one might their own shadow, began speaking to me. It started in the spring, as we placed the first harvest of citrus in the crates. I liked to arrange them in an attractive pile, but Cavaldi always admonished me for trying to make art not money. I had a large cedro in each hand, what Americans always mistook for grapefruit. He called out to me, “Watch how you hold those fruits, eh, Santina? You make a boy have bad thoughts!” I looked at him, appalled, more for the fact that he had spoken directly to me than the inappropriate remark. I couldn’t find an answer. I longed for my mother right then, to whisper a fiery return, but none came. I was mute. I had been silenced for the past four years. The sudden realization stung. I considered lobbing the fruits at him but channeled a pretense of calm. My cheeks reddened, which I know he mistook for paltry modesty, or worse, encouragement, then I fled back into the shop.

I don’t know whether it was my nightly prayers, the incessant daydreams of life elsewhere, the relentless beckoning of my sea and its daily promise of potential escape, or the simple hand of fate, but three years later, on the afternoon of Friday, May 25th—venerdi, named after Venus, harbinger of love and tranquillity—two gentlemen entered my life and altered its course.

Mr. Benn and Mr. George were art dealers from London. They wore linen shirts in pastel shades, hid their eyes behind sunglasses, and spoke without moving their mouths very much. Mr. Benn was the smaller of the two and always held his head at a marginal incline as if he were trying to hear a song passing on the breeze or decipher messages from the shape-shifting clouds above. Mr. George was very tall and looked like he would do well to eat more pasta. His movements were slow and deliberate; his voice full of air. They admired the dancing shimmer of our emerald sea, the yellow of the mimosa tree outside Cavaldi’s store, and knew that cedro fruits were for making exquisite mostarda, a thick jelly sliced thin to accompany cheese. I was easily impressed in those days.

During their stay in Positano, they made daily trips to the store, and I was happy to serve them because they always stopped to stitch together a frayed conversation in their limited Italian. They tried to tell me a little about life in London, while touching every cherry before judging which ought to be included in their half-kilo’s worth. Their words spun another world before me, crisp, colorful pictures of a life I craved. I listened as Mr. Benn offered a steady commentary on what Mr. George was well advised to buy. It was a wondrous thing for me to witness lives that could afford a month’s stay in a tiny Italian town. All sorts of fantasies seared my overused imagination when I served them, underscored with a restlessness that pounded louder for each day I remained within Cavaldi’s prison-like walls.

Every morning, they would stop by and ask what they ought to cook with the fresh zucchini, whether the flowers were better in risotto or fried? How long I’d char an eggplant for and which olive oil would be best for sofritto—finely cut celery, onion, and carrot—and which would be best for drizzling over finely chopped radicchio? I began to look forward to their visits, a beacon of beauty amidst the relentless purgatory of life with Cavaldi. The obvious pleasure they took in enjoying our food made me feel proud. Their enthusiasm about our tomatoes made me wonder whether us locals appreciated the miracle of our bounty, as well as what on earth London art dealers must eat throughout the year to make our simple groceries so compelling?

As we approached the end of June, I had shared most of the recipes I knew, and sometimes, part for folly, part for necessity—as my repertoire was running thin—I’d invent ideas on the spot, improvising appropriate vegetable pairings, hoping they might work in real life too. I remember them arriving at the store, and I prepared myself for a tour of the day’s deliveries. I’d been hatching a few ideas for light summery lunches that I had an inkling they’d enjoy when they asked me something unrelated to anything we’d spoken about before: Would I consider working for them in London in return for papers to America?

I will never forget that day. The way the sun bleached their white faces and lit up their pale yellow collars—they often wore the same shade. Their smiling faces are etched in my mind. Behind them, the ever increasing surge of tourism strolled past the shop. I remember watching the crowd smudge into a sun-kissed blur, the feel of the cold dark shop behind me, and that compelling stone path out of this town, away from this miserable life and the battleaxe for whom I would never be any more than a mountain-girl lackey. They must have known I would have said yes before they’d even finished the invitation. Perhaps I ought to have asked more questions, known what would have been truly expected of me, but the craving for freedom, for air, was too powerful. I think if I’d been even bolder I might have thrown off my apron there and then and walked with them straight onto their ship from the Bay of Naples with nothing but my smock. As it turned out, that was not so far from the truth. On July 1, 1956, I became part of the Neapolitan throng shuffling along the streets of London, in search of gold.

It took six weeks of the purgatorial British drizzle before I surrendered to my first bout of homesickness. At first, the terrifying otherness was the exhilaration of a splash of spring water on a hot day; the sounds of murmured clipped vowels, the way people’s hands stayed by their sides when they spoke. The way the young girls seemed to be talking out the sides of their mouths, whirring a string of incomprehensible sentences, each word looping onto the next, whirring out of what sounded like chewing gum–filled mouths. I wanted to be them. I wanted my hair pinned, curled, and set. I wanted to walk down the street with my arm linked in my best friend’s, surefooted, heels that knew they belonged and where they were headed. But after just over a month of this giddy daydream, the stream of possible lives blurring before me, offering heady futures just beyond my reach, reality hit. I had no one.

Mr. Benn and Mr. George had lost the laid-back sunshine swagger of their holiday. Back in North West London they had become different people. Or rather, they had settled back into the lives they had paused. The gentlemen owned a large Georgian terraced home set a little way back from the main Heath Street that led into Hampstead. The bohemian suburb attracted a vibrant palette of artists, many of which came to call at our house, each more peculiar than the previous. Mr. Benn and Mr. George ran an art gallery on one of the back streets behind Piccadilly. I navigated my way there on my first day off. I stood upon the wooden slats of the tube carriage of the Bakerloo line, turning in a pitiful performance of confidence. Truth was, I could barely read the map in time to work out which stop was mine, so thick was the tiny carriage of others’ cigarette smoke. It reminded me of my father.

When I did arrive, I was too embarrassed to step inside. I remained on the pavement, ignoring the rain. I stared at the painting in the window. Giant swirls of yellow with flecks of turquoise stuck to the canvas in stubborn blobs. Angry spurts of red protested across the central spiral. I couldn’t tear my eyes away. Nothing before me could, in my opinion, be judged as art, yet the image was intimidating in the compelling way it hooked my gaze. The artist and frame had had a fight, and I couldn’t decide who had won.

I left the stalemate and found a tiny booth in the sweaty New Piccadilly Café, sandwiched between the Piccadilly theater and a number of salubrious shop fronts. It was hard to decipher the goods on offer, but I had a hunch it had a lot to do with the young women huddled nearby. It took me a couple of minutes to realize that I had understood every word of what the proprietor said to the waitress. Before I congratulated myself on my progress in English, it dawned on me that the dialect I had tuned into was Neapolitan.

“Signori—you from the old country, sì?”

I looked up at the man, unsure of what my answer ought to be. “Positano.”

“I know a Napoletana when I see one!”

He scooted around the counter, leaving the blaze of short-order cooks whipping up omelettes behind him.

“You’re not long here, am I right, Signorina?”

I had an inkling to suggest that I’d never met a Neapolitan man who ever thought he wasn’t right about anything, but thought better of it.

“You working? Lavori?”

“Yes,” I began, realizing how much I’d cherished my anonymity up till this interrogation, how the incessant Positanese prying was very much part of my past, not present, “for two gentlemen. In Hampstead.”

His eyebrows raised and his head tilted.

“Hey, Carla!” he yelled over to the waitress zipping between tables with egg-smeared plates balanced just the right side of equilibrium, “this signorina is up with the Hampstead crowd! Not one gentleman! Two! Not bad for a fishing village girl, no?”

I was back on my narrow streets, gossip climbing cobbles. I took a breath to speak without knowing what I wanted to say. He quashed my indecision before I could. “Listen, if it doesn’t work out with the lords up there, you call me, sì? Wait—two men you say? Together in one house? Brothers?”

I shook my head. His eyebrows furrowed. I wasn’t convinced that he didn’t mutter something to the Virgin Mary and the saints.

“I always have work for a paesan.” I didn’t want to be a paesan. I wanted to be a Londoner. “This Soho,” he continued, twiddling his fingers in the air like someone sprinkling parmigiano, “this patch belongs to us italiani. Out there we’re immigrants. But in Soho we help each other—capisci?”

I nodded, but I didn’t. Or didn’t want to.

I tried to let go of the vague sense that his approach was more of an offensive than a welcome. Wisdom and scrawled number on limp paper imparted, he turned and walked across the café waving singsong arms at an English couple who were sat at another Formica booth, dipping their rectangular strips of toast into soft-boiled eggs. I took a final sip and left, all remnants of homesickness hanging in the sweaty tea-smudged air of that café.

My attic room is etched in memory. It was clean and simple. My routine was described to me in great detail and it didn’t take me long to adjust to the gentlemen’s habits, which, it would seem, never altered independent of the day. To her credit, Signora Cavaldi’s terse grip had stood me in fine stead for London life.

I hadn’t meant to, nor planned to, but on my sixth visit to the police station the first cracks appeared. Small, but prominent, fissures. I was the tenth in line to have my Certificate of Registration stamped. I held it in my hand, trying not to let my nerves crease it too much. At the top was my number: 096818. And below the words: ALIENS ORDER 1956. Every other visit, I had felt like it would only be a matter of time until I would no longer be alien; I would belong, click into the puzzle, be that final missing piece. But that day, as the drizzle left a damp trail on my hair like half-dried tears, I felt the sting of being the outsider. It was the first time I’d noticed the sideways glances of the people going about their regular days. Or perhaps they had always looked at us like that. I was used to being alone, I told myself. Life here was a world better than the one I’d left behind. I almost convinced myself.

Autumn and winter trundled by, and I couldn’t shake the feeling that Mr. Benn and Mr. George were not impressed by my work. There was nothing major I could pinpoint about the shift in our day-to-day lives. A wave of frustration drew in, a little snatched remark here, an almost imperceptible roll of the eye; the toast being overdone, underdone, too early, not early enough. Minutiae of small failures tripped into an impressive collection, the way insignificant disappointments ferment into resentment between lovers till they can no longer bear to be together but cannot define exactly what pressure has pushed them apart. All three of us knew that I would not be working there much longer.

One morning in early May, the bell rang of a Saturday afternoon, a surprising sun casting boastful rays across the black-and-white tiles of the wide hallway, as if it too had joined in to celebrate my imminent termination of employment. I knew it would be my final weekend here, and I would, against my better judgment, give the owner of New Piccadilly Café a call after all. I turned the latch and opened the door.

Upon the step stood a man and a woman. She had a mane of strawberry blonde locks cascading in defiant curls past her shoulders. They bounced over the deep purple of her full-length woollen cardigan. Her long red chiffon slip beneath danced on the spring breeze by her bare feet, slipped into simple Roman sandals. His beard was a thing to behold, waves of thick blond tuft with streaks of red. A wide-brimmed leather hat perched on his head at an angle. His heavy leather boots stamped a few times upon the mat, scraping off imaginary snow or the memory of yet another wet day. At once, they reminded me of the painting in the window. Only this splash of color and verve came with its very own halo surround, courtesy of the bitter white sun.

I noticed I was staring just before they did and stepped aside to let them in. The woman flashed me a wide smile, flicked the hair off her face and removed her shoes, before floating into the front room where Mr. Benn had insisted I light a fire. She wrapped her arms around him, and I pretended not to notice when she kissed him on the lips and sat on his knee. So did the gentleman who accompanied her. He, rather, shook Mr. George’s hand, who then nodded for me to open the wine.

I filled four glasses with prosecco and handed them out. Mr. Benn and Mr. George carried on talking. The man and the woman thanked me. I returned to the tray and lifted the small bowl of nuts Mr. Benn had asked me to prepare. As I placed them upon the low table before the fire, the woman reached out her hand. “Santina, aren’t you?”

I nodded, wanting to avoid conversation.

“Henry,” she began, turning to the man who had accompanied her, “this is Santina, darling. Oh she’s a pip. You’re like a Mediterranean stroll in the sun—you know you’ve found a beauty, don’t you, boys?”

Mr. Benn and Mr. George smiled, one lip each.

“Santina, it’s a pleasure,” she continued, while I squirmed. “We’ve heard a great deal about you. How exquisite to have a slice of Positano right here in North West London. Henry darling, it fills me with a great deal of hope. It’s like a ray of sun through the fog.”

“That’ll be the morning sun actually doing what it’s compelled to do,” he answered, “quite naturally.”

The woman rolled her eyes and jumped up from Mr. Benn’s lap.

“Quite right—I’m not thinking straight at all—thank God for that! Who’d live a life through logic’s narrow lens, for crying out loud?”

“I’ll drink to that!” cried Mr. George and the four of them stood and clinked.

“Go easy with the wine, Adeline,” Henry, who I had assumed was her husband, replied. Though in this house, when guests appeared, it wasn’t always clear who belonged to whom. The boundaries I had become accustomed to back home were the suffused haze after a spring shower.

The woman’s hand slipped down to her abdomen, “Good heavens, I almost forgot! Yes, we’ve got some marvelous news, haven’t we?”

“Indeed,” Henry replied, catching my eye as he did so.

“I shall be creating more than paintings this year, gentlemen!” she cried, flinging her arms up at such a speed that she almost lost half her glass’s contents onto the Persian rug underfoot. “I am now producing humans also!”

It was hard to follow the conversation with accuracy, especially since I hadn’t been allowed into or out of it. I could understand that the willowy figure before me was pregnant. As she stood up, it became so obvious that I wondered how I hadn’t noticed before.

“Congratulations, Mr. and Mrs. Crabtree!” cried Mr. George.

“That’ll be all, Santina,” Mr. Benn said, with an unnecessary hand wave, adding to all the other spoken and unspoken gestures tracing my paper cut scars.

I shut the door behind me and went upstairs to pack.

The next morning Mr. Benn and Mr. George called me to the back parlor. I found Mr. Benn by his grand piano looking out toward the glass doors that led to their garden. He was puffing on a thin cigar. The smoke reached me in sorrowful swirls.

“Santina, my dear. It will come as somewhat of a surprise, to me more than anyone, that we can no longer offer you employment.”

I gave a mute nod, unsure whether to express regret or surprise. Neither surfaced as it happened.

“However, there are others in our circle who are more than willing to welcome you into their home and have you offer the tireless support you have given us, up till now.”

I glanced over at Mr. George, but he was looking off toward an invisible horizon behind me.

“Mr. and Mrs. Crabtree are keen for you to start with them right away. The major, for that is how you must address him from now on, has assured me that he will, like us, arrange your papers for America after your first year.”

He left a pause here, which I knew he expected me to fill with grateful acceptance. I was happy that we were parting company with relative grace. Or, if not grace, at the very least that smooth veneer of some such which I had intuited was an impeccable British habit. That evening they walked me down the hill toward the heart of Hampstead village to my new home.

Adeline and the major’s house snuck into a slice of land between larger old brick homes at the convergence of two narrow lanes. Its layout was more warren than house, with low-ceilinged rooms leading onto one another in a maze of unexpected connections. Tudor beams hung crooked with age. Persian rugs overlapped one another in most of the rooms. A huge hearth stood in the main living room flanked by two sofas of different shades of velveteen violet. There were masks upon the wall, Indian gods and goddesses forever mid-chase, flaunting their half-clothed bodies, or leering at the spectator. I’m ashamed to admit that I avoided looking at the one which hung by my bedroom door, so full were its wooden carved eyes of malice. Its pupils were painted red and black and hair hung in sad curls a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...