- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

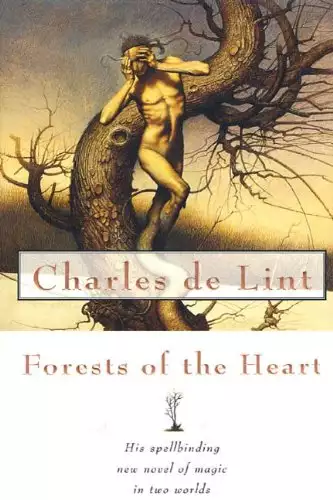

In the Old Country, they called them the Gentry: ancient spirits of the land, magical, amoral, and dangerous. When the Irish emigrated to North America, some of the Gentry followed … only to find that the New World already had spirits of its own, called manitou and other such names by the Native tribes.

Now generations have passed and the Irish have made homes in the new land, but the Gentry still wander homeless on the city streets. Gathering in the city shadows, they bide their time and dream of power. As their dreams grow harder, darker, fiercer, so do the Gentry themselves—appearing to those with the sight to see them, as hard and dangerous men, invariably dressed in black.

Bettina can see the Gentry, and knows them for what they are. Part Indian, part Mexican, she was raised by her grandmother to understand the spirit world. Now she lives in Kellygnow, a massive old house run as an arts colony on the outskirts of Newford, a world away from the Southwestern desert of her youth. Outsider her nighttime window, she often spies the dark men, squatting in the snow, smoking, brooding, waiting. She calls them los lobos, the wolves, and stays clear of them—until the night one follows her to the woods, and takes her hand …

Ellie, an independent young sculptor, is another with magic in her blood, but she refuses to believe it, even though she too sees the dark men. A strange old woman has summoned Ellie to Kellygnow to create a mask for her based on an ancient Celtic artifact. It is the mask of the mythic Summer King—another thing Ellie does not believe in. Yet lack of belief won’t dim the power of the mask, or its dreadful intent.

Donal, Ellie’s former lover, comes from an Irish family and knows the truth at the heart of the old myths. He thinks he can use the mask and the “hard men” for his own purposes. And Donal’s sister, Miki, a punk accordion player, stands on the other side of the Gentry’s battle with the Native spirits of the land. She knows that more than her brother’s soul is at stake. All of Newford is threatened, human and mythic beings alike.

Once again Charles de Lint weaves the mythic traditions of many cultures into a seamless cloth, bringing folklore, music, and unforgettable characters to life on modern city streets.

Release date: August 11, 2001

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Forests of the Heart

Charles de Lint

Los lobos

El lobo pierde los dientes más no las mientes,

The wolf loses his teeth, not his nature.—Mexican-American saying

Like her sister, Bettina San Miguel was small, slender woman in her mid-twenties, dark-haired and darker-eyed; part Indio, part Mexican, part something older still. Growing up, they'd often been mistaken for twins, but Bettina was a year younger and, unlike Adelita, she had never learned to forget. The little miracles of the long ago lived on in her, passed down to her from their abuela, and her grandmother before her. It was a gift that skipped a generation, tradition said.

"¡Tradición, pah!" their mother was quick to complain when the opportunity arose. "You call it a gift, but I call it craziness."

Their abuela would nod and smile, but she still took the girls out into the desert, sometimes in the early morning or evening, sometimes in the middle of the night. They would leave empty-handed, be gone for hours and return with full bellies, without thirst. Return with something in their eyes that made their mother cross herself, though she tried to hide the gesture.

"They miss too much school," she would say.

"Time enough for the Anglos' school when they are older," Abuela replied.

"And church? If they die out there with you, their sins unforgiven?"

"The desert is our church, its roof the sky. Do you think the Virgin and los santos ignore us because it has no walls? Remember, hija, the Holy Mother was a bride of the desert before she was a bride of the church."

Mamá would shake her head, muttering, "Nosotras estamos locas todas." We are all crazy. And that would be the end of it. Until the next time.

Then Adelita turned twelve and Bettina watched the mysteries fade in her sister's eyes. She still accompanied them into the desert, but now she brought paper and a pencil, and rather than learn the language of la lagartija, she would try to capture an image of the lizard on her paper. She no longer absorbed the history of the landscape; instead she traced the contours of the hills with the lead in her pencil. When she saw el halcón winging above the desert hills, she saw only a hawk, not a brujo or a mystic like their father, caught deep in a dream of flight. Her own dreams were of boys and she began to wear makeup.

All she had learned, she forgot. Not the details, not the stories. Only that they were true.

But Bettina remembered.

"You taught us both," she said to her abuela one day when they were alone. They sat stone-still in the shadow cast by a tall saguaro, watching a coyote make its way with delicate steps down a dry wash. "Why is it only I remember?"

The coyote paused in mid-step, lifting its head at the sound of her voice, ears quivering, eyes liquid and watchful.

"You were the one chosen," Abuela said.

The coyote darted up the bank of the wash, through a stand of palo verde trees, and was gone. Bettina turned back to her grandmother.

"But why did you choose me?" she asked.

"It wasn't for me to decide," Abuela told her. "It was for the mystery. There could only be one of you, otherwise la brujería would only be half so potent."

"But how can she just forget? You said we were magic—that we were both magic."

"And it is still true. Adelita won't lose her magic. It runs too deep in her blood. But she won't remember it, not like you do. Not unless…"

"Unless what?"

"You die before you have a granddaughter of your own."

* * *

Tonight Bettina sat by the window at a kitchen table many miles from the desert of her childhood, the phone propped under one ear so that she could speak to Adelita while her hands remained free to sort through the pile of milagros spilled across the table. Her only light source was a fat candle that stood in a cracked porcelain saucer, held in place by its own melted wax.

She could have turned the overhead on. There was electricity in the house—she could hear it humming in the walls and it made the old fridge grumble in the corner from time to time—but she preferred the softer illumination of the candle to electric lighting. It reminded her of firelight, of all those nights sitting around out back of Adelita's house north of Tubac, and she was in a campfire mood tonight. Talking with her sister did that, even if they were a half continent and a few time zones apart, connected only by the phone and the brujería in their blood.

The candlelight glittered on the small silver votive offerings and mad shadows dance in the corners of the room whenever Bettina moved her arm. Those shadows continued to dance when the candle's flame pointed straight up at the ceiling once more, but she ignored them. They were like the troubles that come in life—the more attention one paid to them, the more likely they were to stay. They were like the dark-skinned men who had gathered outside the house again tonight.

Every so often they came drifting up through the estates that surrounded Kellygnow, a dozen or so tall, lean men, squatting on their haunches in a rough circle in the backyard, eyes so dark they swallowed light. Bettina had no idea what brought them. She only knew they were vaguely related to her grandmother's people, distant kin to the desert Indios whose blood Bettina and Adelita shared—very distant, for the memory of sea spray and a rich, damp green lay under the skin of their thoughts. This was not their homeland; their spirits spread a tangle of roots just below the surface of the soil, no deeper.

But like her uncles, they were handsome men, dark-skinned and hard-eyed, dressed in collarless white shirts and suits of black broadcloth. Barefoot, calluses hard as boot leather, and the cold didn't seem to affect them. Long black hair tied back, or twisted into braided ropes. They were silent, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes as they watched the house. Bettina could smell the burning tobacco from inside where she sat, smell the smoke, and under it, a feral, musky scent.

Their presence in the yard resonated like a vibration deep in her bones. She knew they lived like wolves, up in the hills north of the city, perhaps, running wild and alone except for times such as this. She had never spoken to them, never asked what brought them. Her abuela had warned her a long time ago not to ask questions of la brujería when it came so directly into one's life. It was always better to let such a mystery make its needs known in its own time.

"And of course, Mamá wants to know when you're coming home," Adelita was saying.

Usually they didn't continue this old conversation themselves. Their mother was too good at keeping it alive by herself.

"I am home," Bettina said. "She knows that."

"But she doesn't believe it."

"This is true. She was asking me the same thing when I talked to her last night. And then, of course, she wanted to know if I'd found a church yet, if the priest was a good speaker, had I been to confession…"

Adelita laughed. "iPor supuesto! At least she can't check up on you. Chuy's now threatening to move us to New Mexico."

"Why New Mexico?"

"Because of Lalo's band. With the money they made on that last tour, they had enough to put a down payment on this big place outside of Albuquerque. But it needs a lot of work and he wants to hire Chuy to do it. Lalo says there's plenty of room for all of us."

"Los lobos."

"That's right. You should have come to one of the shows."

But Bettina hadn't been speaking of the band from East L.A. Those lobos had given Lalo's band their big break by bringing them along on tour as their support act last year. The wolves she'd been referring to were out in the cold night that lay beyond the kitchen's windows.

She hadn't even meant to speak aloud. The words had been pulled out of her by a stirring outside, an echoing whisper deep in her bones. For a moment she'd thought the tall, dark men were coming into the house, that an explanation would finally accompany their enigmatic presence. But they were only leaving, slipping away among the trees.

"Bettina?" her sister asked. "¿Estás ahi"

"I'm here."

Bettina let out a breath she hadn't been aware of holding. She didn't need to look out the window to know that the yard was now empty. It took her a moment to regain the thread of their conversation.

"I was just distracted for a moment," she said, then added, "What about the gallery? I can't imagine you selling it."

Adelita laughed. "Oh, we're not really going. It's bad enough that Lalo's moving so far away. Chuy's family would be heartbroken if we went as well. How would they be able to spoil Janette as much as they do now? And Mamá…"

"Would never forgive you."

"De veras"

Bettina went back to sorting through her milagros, fingering the votive offerings as they gossiped about the family and neighbors Bettina had left behind. Adelita always had funny stories about the tourists who came into the gallery and Bettina never tired of hearing about her niece Janette. She missed the neighborhood and its people, her family and friends. And she missed the desert, desperately. But something had called to her from the forested hills that lay outside the city that was now her home. It had drawn her from the desert to this place where the seasons changed so dramatically: in summer so green and lush it took the breath away, in winter so desolate and harsh it could make the desert seem kind. The insistent mystery of it had nagged and pulled at her until she'd felt she had no choice but to come.

She didn't think the source of the summons lay with her uninvited guests, los lobos who came into the yard to smoke their cigarettes and silently watch the house. But she was sure they had some connection to it.

"What are you doing?" Adelita asked suddenly. "I keep hearing this odd little clicking sound."

"I'm just sorting through these milagros that Inés sent up to me. For a…" She hesitated a moment. "For a fetish."

"Ah." Adelita didn't exactly disapprove of Bettina's vocation—not like their mother did—but she didn't quite understand it either. While she also drew on the stories their abuela had told them, she used them to fuel her art. She thought of them as fictions, resonant and powerful, to be sure, but ultimately quaint. Outdated views from an older, more superstitious world that were fascinating to explore because they jump-started the creative impulse, but not anything by which one could live in the modern world.

"Leave such things for the storytellers," she would say.

Such things, such things. Simple words to encompass so much.

Such as the fetish Bettina was making at the moment, part mojo charm, part amuleto: a small, cotton sack that would be filled with dark earth to swallow bad feelings. Pollen and herbs were mixed in with the earth to help the transfer of sorrow and pain from the one who would wear the fetish into the fetish itself. On the inside of the sack, tiny threaded stitches held a scrap of paper with a name written on it. A hummingbird's feather. A few small colored beads. And, once she'd chosen exactly the right milagro, one of the silver votive offerings that Inés had sent her would be sewn inside as well.

Viewed from outside, the stitches appeared to spell words, but they were like the voices of ravens heard speaking in the woods. The sounds made by the birds sounded like words, but they weren't words that could be readily deciphered by untrained ears. They weren't human words.

This was one of the ways she focused her brujería. Other times, she called on the help of the spirits and los santos to help her interpret the cause of an unhappiness or illness.

"There is no one method of healing," her grandmother had told her once. "Just as la Virgen is not bound by one faith."

"One face?" Bettina had asked, confused.

"That, too," Abuela said, smiling. "La medicina requires only your respect and that you accept responsibility for all you do when you embark upon its use."

"But the herbs. The medicinal plants…"

"Por eso," Abuela told her. "Their properties are eternal. But how you use them, that is for you to decide." She smiled again. "We are not machines, chica. We are each of us different. Sin par. Unique. The measure given to one must be adjusted for another."

There was not a day gone by that Bettina didn't think of and miss her grandmother. Her good company. Her humor. Her wisdom. Sighing, she returned her attention to her sister.

"You can't play at the brujería all your life," Adelita was saying, her voice gentle.

"It's not play for me."

"Bettina, we grew up together. You're not a witch."

"No, I'm a healer."

There was an immense difference between the two, as Abuela had often pointed out. A bruja made dark, hurtful magic. A curandera healed.

"A healer," Bettina repeated. "As was our abuela."

"Was she?" Adelita asked.

Bettina could hear the tired smile in Adelita's voice, but she didn't share her sister's amusement.

"¿Como" she said, her own voice sharper than she intended. "How can you deny it?"

Adelita sighed. "There is no such thing as magic. Not here, in the world where we live. La brujerí only for stories. Por el reino de los sueños. It lives only in dreams and make-believe."

"You've forgotten everything."

"No, I remember the same as you. Only I look at the stories she told us with the eyes of an adult. I know the difference between what is real and what is superstition."

Except it hadn't only been stories, Bettina wanted to say.

"I loved her, too," Adelita went on. "It's just…think about it. The way she took us out into the desert. It was like she was trying to raise us as wild animals. What could Mamá have been thinking?"

"That's not it at all—"

"I'll tell you this. Much as I love our mamá, I wouldn't let her take Janette out into the desert for hours on end the way she let Abuela take us. In the heat of the day and…how often did we go out in the middle of the night?"

"You make it sound so wrong."

"Cálmate, Bettina. I know we survived. We were children. To us it was simply fun. But think of what could have happened to us—two children out alone in the desert with a crazy old woman."

"She was not—"

"Not in our eyes, no. But if we heard the story from another?"

"It…would seem strange," Bettina had to admit. "But what we learned—"

"We could have learned those stories at her knee, sitting on the front stoop of our parents' house."

"And if they weren't simply stories?"

"¡Qué boba eres! What? Cacti spirits and talking animals? The past and future, all mixed up with the present. What did she call it?"

"La época del mito."

"That's right. Myth time. I named one of my gallery shows after it. Do you remember?"

"I remember."

It had been a wonderful show. La Gata Verde had been transformed into a dreamscape that was closer to some miraculous otherwhere than it was to the dusty pavement that lay outside the gallery. Paintings, rich with primary colors, depicted los santos and desert spirits and the Virgin as seen by those who'd come to her from a different tradition than that put forth by the papal authority in Rome. There had been Hopi kachinas—the Storyteller, Crow Woman, clowns, deer dancers—and tiny, carved Zuni fetishes. Wall hangings rich with allegorical representations of Indio and Mexican folklore. And Bettina's favorite: a collection of sculptures by the Bisbee artist, John Early—surreal figures of gray, fired clay, decorated with strips of colored cloth and hung with threaded beads and shells and spiraling braids of copper and silver filament. The sculptures twisted and bent like smoke-people frozen in their dancing, captured in mid-step as they rose up from the fire.

She had stood in the center of the gallery the night before the opening of the show and turned slowly around, drinking it all in, pulse drumming in time to the resonance that arose from the art that surrounded her. For one who didn't believe, Adelita had still somehow managed to gather together a show that truly seemed to represent their grandmother's description of a moment stolen from la época del mito.

"Not everything in the world relates to art," Bettina said now into the phone.

"No. But perhaps it should. Art is what sets us apart from the animals."

Bettina couldn't continue the conversation. At times like this, it was as though they spoke two different languages, where the same word in one meant something else entirely in the other.

"It's late," she said. "I should go."

"Perdona, Bettina. I didn't mean to make you angry."

She wasn't angry, Bettina thought. She was sad. But she knew her sister wouldn't understand that either.

"I know," she said. "Give my love to Chuy and Janette."

"Sí. Vaya con Dios."

And if He will not have me? Bettina thought. For when all was said and done, God was a man, and she had never fared well in the world of men. It was easier to live in la época del mito of her abuela. In myth time, all were equal. People, animals, plants, the earth itself. As all times were equal and existed simultaneously.

"Qué te vaya bien," she said. Take care.

She cradled the receiver and finally chose the small shape of a dog from the milagros scattered across the tabletop. El lobo was a kind of a dog, she thought. Perhaps she was making this fetish for herself. She should sew her own name inside, instead of Marty Gibson's, the man who had asked her to make it for him. Ah, but would it draw los lobos to her, or keep them away? And which did she truly want?

Getting up from the table, she crossed the kitchen and opened the door to look outside. Her breath frosted in the air where the men had been barefoot. January was a week old and the ground was frozen. It had snowed again this week, after a curious Christmas thaw that had left the ground almost bare in many places. The wind had blown most of the snow off the lawn where the men had gathered, pushing it up in drifts against the trees and the buildings scattered among them: cottages and a gazebo, each now boasting a white skirt. She could sense a cold front moving in from the north, bringing with it the bitter temperatures that would leave fingers and face numb after only a few minutes of exposure. Yet some of the men had been in short sleeves, broadcloth suit jackets slung over their shoulders, all of them walking barefoot on the frozen lawn.

Por eso.…

She didn't think they were men at all.

"Your friends are gone."

"Ellos no son mis amigos," she said, then realized that speaking for so long with Adelita on the phone had left her still using Spanish. "They aren't my friends," she repeated. "I don't know who, or even what they are."

"Perhaps they are ghosts."

"Perhaps," Bettina agreed, though she didn't think so. They were too complicated to be described by so straightforward a term.

She gazed out into the night a moment longer, then finally closed the door on the deepening cold and turned to face the woman who had joined her in the kitchen.

If los lobos were an elusive, abstracted mystery, then Nuala Fahey was one much closer to home, though no more comprehendible. She was a riddling presence in the house, her mild manner at odds with the potent brujería Bettina could sense in the woman's blood. This was an old, deep spirit, not some simple ama de llaves, yet in the nine months that Bettina had been living in the house, Nuala appeared to busy herself with no more than her housekeeping duties. Cleaning, cooking, the light gardening that Salvador left for her. The rooms were always dusted and swept, the linens and bedding fresh and sweet-smelling. Meals appeared when they should, with enough for all who cared to partake of them. The flower gardens and lawns were well-tended, the vegetable patch producing long after the first frost.

She was somewhere in her mid—forties, a tall, handsome woman with striking green eyes and a flame of red hair only vaguely tamed into a loose bun at the back of her head. While her wardrobe consisted entirely of men's clothes—pleated trousers and dress shirts, tweed vests and casual sports jackets—there was nothing mannish about her figure or her demeanor. Yet neither was she as passive as she might seem. True, her step was light, her voice soft and low. She might listen more than she spoke, and rarely initiate a conversation as she had this evening, but there was still that undercurrent of brujería that lay like smoldering coals behind her eyes. La brujería, and an impression that while the world might not always fully engage her, something in it certainly amused her.

Bettina had been trying to make sense of the housekeeper ever since they'd met, but she was no more successful now, nine months on, than she'd been the first day Nuala opened the front door and welcomed her into Kellygnow, the old house at the top of the hill that was now her home. Kellygnow she learned after she moved in, meant "the nut wood" in some Gaelic language—though no one seemed quite sure which one. But there were certainly nut trees on the hill. Oak, hazel, chestnut.

There were many things Bettina hadn't been expecting about this place Adelita had found for her to stay. The mystery of Nuala was only one of them. Kellygnow was much bigger than she'd been prepared for, an enormous rambling structure with dozens of bedrooms, studios, and odd little room-sized nooks, as well as a half-dozen cottages in the woods out back. The property was larger, too—especially for this part of the city—taking up almost forty acres of prime real estate. With the neighboring properties ranging in the million-dollar-and-up range, Bettina couldn't imagine what the house and its grounds were worth. Its neighbors were all owned by stockbrokers and investors, bankers and the CEOs of multinational corporations, celebrities and the nouveau riche—a far cry from the bohemian types Bettina shared her lodgings with.

For Kellygnow was a writers' and artists' colony, founded in the early 1900s by Sarah Hanson, a descendant of the original owner. She had been a respected artist and essayist in her time, a rarity at the turn of the century, but was now better remembered for the haven she had created for her fellow artists and writers.

The colony was the oldest property in the area, standing alone at the top of Handfast Road with a view that would do the Newford Tourist Board's pamphlets proud. There was a tower, four stories high in the northwest corner of the house. From the upper windows of one side you could look down on the city: Ferryside, the river, Foxville, Crowsea, downtown, the canal, the East Side. At night, the various neighborhoods blended into an Indio traders' market, the lights spread out like the sparkling trinkets on a hundred blankets. From another window you could see, first the estates that made up the Beaches; below them, rows of tasteful condos blending into the hillside; beyond them, the lakefront properties; and then finally the lake itself, shimmering in the starlight, ice rimming the shore in thick, playful displays of abstract whimsy. Far in the distance the ice thinned out, ending in open water.

The view behind the house was blocked by trees. Hazels and chestnuts. Tamaracks and cedar, birch and pine. Most impressive were the huge towering oaks that, she learned later, were thought to be part of the original growth forest that had once laid claim to all the land in an unbroken sweep from the Kickaha Mountains down to the shores of the lake. These few giants had been spared the axes of homesteaders and lumbermen alike by the property's original owner, Virgil Hanson, whose home had been one of the cottages that still stood out back. It was, Bettina had been told, the oldest building in Newford, a small stone croft topping the wooded hill long before the first Dutch settlers had begun to build along the shores of the river below.

Adelita had never lived in Kellygnow, but before moving back home to Tubac and opening her gallery, she had studied fine art at Butler University and some of her crowd had been residents. It would be the prefect place for Bettina, she said. Let her handle it. She would make a few calls. Everything would be arranged.

"I'm not an artist or a writer," Bettina had said.

"No, but you're an excellent model and in that house, one good model would be more welcome than a dozen of the world's best artists. Créeme. Trust me. Only don't tell Mamá or she'll have both our heads."

No, Bettina had thought. Mamá would definitely not approve. Mamá was already upset enough that Bettina was moving. If she were to know that her youngest daughter expected to make her living by being paid to sit for artists, often in the nude, she would be horrified.

Bettina had thought to only stay in the house for as long as it took her to find an apartment in the city. She was given one of the nooks to make her own—a small space under a staircase that opened up into a hidden room twice the size of her bedroom at home. There was a recessed window looking out on the backyard, overhung with ivy on the outside and with just room enough for her to sit on its sill if she pulled her knees up to her chin. There was also a single brass bed with shiny, knobbed posts and a cedar chest at its foot that lent the room a resonant scent. A small pine armoire. A worn, black leather reading chair with a tall glass-shaded lamp beside it, both "borrowed" from the library at some point, she was sure, since they matched its furnishings. And wonder of wonders, a piece of John Early's work: a gray, fired-clay sculpture of the Virgin wearing a quizzical smile, blue-robed and decorated with a halo of porcupine quills cunningly worked into the clay and painted gold. In front of the statue, that first day, she found a half-burned candle—someone had been using the statue as the centerpiece for their own small chapel of the Immaculata, she'd thought at first. Or perhaps they had simply enjoyed candlelight as much as she did.

Either way, she felt welcomed and blessed.

The one week turned into a month. Adelita had been right. The artists were delighted to have her in residence, constantly vying for her time in their studios. They were good company, as were the writers who only emerged from their quarters at odd times for meals or a sudden need to hear a human voice. And if their intentions were sometimes less than honorable—women as well as men—they were quick to respect her wishes and put the incident behind them.

The one month stretched into three, four. She needed no money for either rent or board, and had barely touched the savings she'd brought with her. Most mornings she sat for one or another of the artists, sometimes for a group of them. Her afternoons and evenings were usually her own. At first she explored the city, but when the weather turned colder, she cocooned in the house, reading, listening to music in one or another of the communal living rooms, often spending time in the company of the gardener Salvador and helping him prepare the property for winter.

And she began to trade her fetishes and charms. First to some of those living in the house, then to customers the residents introduced her to. As her abuela had taught her, she set no fee, asked for no recompense, but they all gave her something anyway. Mostly money, but sometimes books they thought she would like, or small pieces of original art—sketches, drawings, color studies—which she preferred the most. Her walls were now decorated with her growing hoard of art while a stack of books rose thigh-high from the floor beside her chair.

The few months grew into a half year, and now the house felt like a home. She was no closer to discovering what had drawn her to this city, what it was that whispered in her bones from the hills to the north, but it didn't seem as immediate a concern as it had when she'd first stepped off the plane, her small suitcase in one hand, her knapsack on her back with its herbs, tinctures, and the raw materials with which she made her fetishes. The need to know was no longer so important. Or perhaps she was growing more patient—a concept that would have greatly amused her abuela. She could wait for the mystery to come to her.

As she knew it would. Her visions of what was to come weren't always clear, especially when they related to her, but of this she was sure. She had seen it. Not the details, not when or exactly where, or even what face the mystery would present to her. But she knew it would come. Until then, every day was merely another step in the journey she had undertaken when she first began to learn the ways of the spirit world at the knee of her abuela, only now the days took her down a road she no longer recognized, where the braid of her Indio and Mexican past became tangled with threads of cultures far less familiar.

But she was accepting of it all, for la época del mito had always been a confusing place for her. When she was in myth time, she was often too easily distracted by all the possibilities: that what had been might really be what was to come, that what was to come might be what already was. Mostly she had difficulty with the true face of a thing. She mixed up its spirit with its physical presence. Its true essence with the mask it might be wearing. Its history with its future. It didn't help that Newford was like the desert, a place readily familiar with spirits and ghosts and strange shifts in what things seemed to be. Where many places only held a quiet whisper of the otherwhere, here thousands of voices murmured against one another and sometimes it was hard to make out one from the other.

The house at the top of Handfast Road where she now lived was a particularly potent locale. Kellygnow and its surrounding wild acres appeared to be a crossroads between time zones and spirit zones, something that had seemed charming and pleasantly mysterious until los lobos began to squat in its backyard, smoking their cigarettes and watching, watching. Now she could

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...