- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

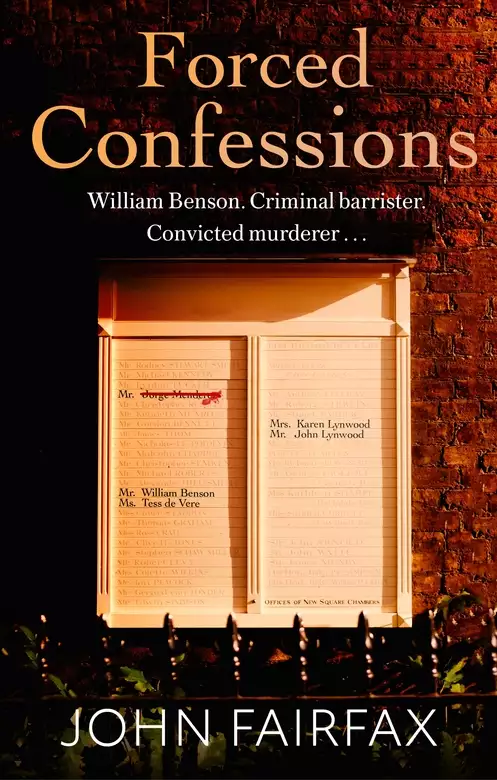

William Benson.

Criminal barrister.

Convicted murderer....

Convicted of murder sixteen years ago, William Benson is ostracised by the establishment and his family. Supported by a close-knit group including solicitor Tess de Vere, he's defied them all and opened his own Chambers. Now he faces the case of his life - and the terminal illness of Helen Camberley who helped him leave his prison life behind

Jorge Menderez, a doctor from Spain, has been found dead in a deserted warehouse in East London. A troubled man, he'd turned to counsellor Karen Lynwood seeking help. Now Karen's husband, John, is accused of his murder. Who is Menderez, and why did he come to London? Benson is defending the couple against seemingly impossible odds, while secrets from his own past threaten to overwhelm him...

Praise for Summary Justice and Blind Defence

'Assured storytelling and highly intriguing moral complexity. I tore through it' Chris Brookmyre

'The courtroom scenes are brilliant, and Benson really comes alive under pressure. Stubborn, fitful and contradictory, he's a highly individualised creation' Spectator

'Punchy dialogue and devious plotlines . . . compelling' The Times

Release date: April 1, 2021

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Forced Confessions

John Fairfax

‘It’s the mark of Cain.’

Camberley recoiled.

‘Don’t say that. You must never say that again.’

‘It’s the truth.’

‘No, it isn’t. We both know it isn’t.’

‘We both know it doesn’t matter what the truth is any more.’

Only a few months ago Benson had been in his second year of a philosophy degree. He’d toyed with the idea of tattoos. Something aesthetic; and linked to grammar – an obsession of the logical positivists. He’d thought of an exclamation mark on his chest and a question mark on his back. He’d ended up with a string of full stops on each arm.

‘They’ll fade,’ he said, pulling down his sleeves.

‘I’ll pay for their removal.’

‘The conviction will remain, Miss Camberley. I might as well keep them.’

Four days earlier, Benson had been dragged into a pelly on D Wing. There, with a needle, blue ink and toilet paper, the job had been done. Twelve dots. Four on the inside of one arm and eight on the other, a jab and a dab for each letter in the name Paul Harbeton. ‘It doesn’t matter if you’re innocent,’ the screw had said, watching. ‘You’ve been convicted.’ There’d been a Zippo as well, to sterilise the needle and light the burns of the onlookers, all of them branded in the same way; all of them lifers for murder, members of the most exclusive club in the prison system.

‘No,’ said Camberley. ‘You cannot keep those . . . mutilations.’

Prior to his trial, she’d leafed imperiously through the witness statements. At times, he’d even wondered if she was glad he’d been charged, for he’d sensed in Helen Camberley QC – silver-haired, with eyes like burning jet – the white-knuckle vanity of the virtuoso. She was going to show Benson how it was done.

‘I owe you an apology,’ she said, sitting down.

‘You gave me a fighting chance. You fought—’

‘And I lost. And all I can tell you is that I’ve never wanted to win a case more than yours; or feel more responsible for . . .’ – embarrassed, she focused on the stained walls, then the broken light, and finally the worn-out lino. She held her breath, as if wondering what to do with it, and finally she let it go, as so much waste. ‘Perhaps one day you might forgive me.’

Benson blamed her for nothing. In court she’d been cajoling, inquiring, indignant, rousing – he’d been mesmerised. His one fleeting concern – dismissed at the time as ignoble – was that maybe, just maybe, she’d tried too hard. That energy hadn’t diminished in the slightest.

‘Last week you said you were resolved to come to the Bar?’

‘I did.’

‘You’ve reflected on my advice?’

‘I have.’

‘Good. Because I, too, have given considerable thought to your future. Have you seen A Man for All Seasons?’

‘No.’

‘A pity. It’s about the life of Thomas More. At one point, he tries to steer a man away from moral catastrophe. Because his professional ambitions are misplaced. More urges him to abandon them and consider teaching. It’s a quiet life, he says; and I say to you—’

‘I don’t want to teach.’

‘Why not?’

‘I want to be like you.’

‘Me?’

‘Yes. I want to question people who think they know the truth.’

‘But you can do that in the classroom. The mind, too, can be a prison. You can open—’

‘I’d rather keep them out of places like this.’

‘And live with failure, like I must?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, that’s admirable; and of no significance.’

She’d already told Benson why. And she repeated it with agitation. You can’t become a barrister without joining one of the four Inns of Court. To do so, you’d have to disclose your conviction . . . and since you pleaded not guilty, you’d have to admit the murder you didn’t commit. And she came to a halt, dismayed, guessing – correctly – that Benson had already written to the Parole Board in those terms. He said:

‘Is there a law that forbids someone with a conviction for murder from practising at the Bar?’

‘No. But—’

‘An Order made by the Secretary of State?’

‘No.’

‘Any rules or regulations published by the Bar Council?’

‘No. Will, stop this. You’re—’

‘Any guidelines restricting the exercise of discretion?’

‘I don’t know and it makes no damned difference. They’ll slam the door in your face.’

‘But it’s possible? Theoretically?’

‘Forget the theory. You’re not a “fit and proper person”.’

‘You don’t need to tell me that.’ Benson tugged up his sleeves. ‘The fit and proper person I once was is dead and gone. I’m starting again. But these dots won’t define what is fit and proper . . . they won’t determine what I do with my new life. I won’t forget the theory. It’s all I’ve got left.’

Camberley went to the barred window and looked over the expanse of slate, chipped brick and barbed wire, towards the gas works, and, beyond that, the distant shops and restaurants of Kensington. Turning a bangle round and round her wrist, she stared as if straining to distinguish someone through the summer haze.

‘Dead and gone?’

‘For ever.’

She became quite still; then she returned to the table with its bent legs bolted to the floor. Although she was short, her voice had an authority that conjured stature. Gazing down at Benson through two half-moons of glass, she seemed far away, in a cold place.

‘I’ll help you challenge the inconceivable. But on one condition.’

‘Name it.’

‘Dying isn’t enough. There can be no resurrection.’

Benson nodded, but his agreement had come too quickly. Camberley became irritated:

‘An advocate must be free. Free from any kind of external pressure or internal distraction. All that matters is the client. Their case, as they see it, supported or unsupported by the evidence. Not as seen by the Crown, or the media, or pressure groups, or the armchair critic. And certainly not as seen through the eyes of an embittered victim of injustice. Some may have the detachment to look beyond their pain. But not a few don’t. They live out their anger finding common cause with those they would help. That is fatal for an advocate. And fatal for the client. Your vocation is to become someone else’s voice; not give them your own. This means you must only look forward. You cannot look back in a search for lost innocence.’

‘I understand.’

‘And neither can anyone else. Not your mother, not your father, not your brother, not your lover. What is dead is dead. If that life is gone, then you must leave it buried.’

‘I will.’

He would become a disciple. And it would cost him nothing.

‘I’ll never look back.’

After a long moment Camberley’s expression softened. A warming vulnerability appeared in her eyes, and she said:

‘From now on, call me Helen.’

With that she went to the door and gave it a knock to summon a guard. Turning suddenly around, she said:

‘We’ll never speak of your case again. So let this be the final word: whoever killed Paul Harbeton lives in a hell of their own making. And unless they admit their crime, they’ll remain there for ever. You can take some comfort in that.’

A key rattled in the lock and Benson felt the misty onset of panic. His respite was over. He was going to be banged up for twenty-three hours a day with Needles. Through a choking fog of tobacco and anxiety he saw him slouched on the toilet, legs wide open, farting and knitting. The guard shoved open the door.

‘How do you know?’ said Benson, and Camberley gazed at him, overrun by an abrupt compression of empathy and accusation. Her voice was barely audible:

‘Getting away with murder always comes at a price.’

‘I’m dying, Will,’ said Camberley, striking a match to light a cigar.

George Braithwaite, sporting a holly and ivy patterned tie, had just taken his unsteady leave. It was late now, and Camberley had returned to the dining room with a bottle of something special, bought long ago, when she’d planned ahead for those ordinary moments that suddenly turn into a celebration.

‘Dying?’ Benson repeated, as if it was a foreign word.

Camberley smiled: ‘Yes. I suppose I should be frightened; but I’m not.’

Benson felt nothing. Then, very slowly, his chair seemed to tip backwards.

‘How do you know?’

‘I’ve got lung cancer.’ With a flick of her wrist, she extinguished the growing flame.

‘What?’

‘Never ask a useless question.’

‘You’re having treatment?’

‘There’s no point. It’s everywhere.’

‘But surely—’

‘I mean everywhere.’

‘It can be slowed down, Helen. There’s—’

‘Not mine.’ She paused to adjust her paper crown. ‘It’s in my lungs. My lymph nodes. My bone marrow. My organs. My brain.’ She sounded like a pathologist reading labels on a row of glass jars. Savouring the brown aroma of Cuba, she said, ‘I’m banjaxed.’

Benson felt the beginnings of a headache.

‘How long did they give you?’

‘Oh, I wasn’t listening. A few weeks or so.’

They were quiet together – as they’d often been in the past after they’d talked themselves dry, dissecting trials and witnesses; scoundrel advocates and rising stars; shrewd judges and the odd dimwit who should never have been appointed. Arching a brow, she appraised the hot, creeping ash at the end of her cigar.

‘I would have liked to go in late spring, with the wisteria out of control. Pull another cracker, will you?’

That conversation had taken place on Christmas Day. A wet and cloudy Sunday. It was now mid-January. Another cloudy Sunday, and even wetter. Camberley’s paper crown had been replaced by a transparent PVC ventilation helmet that reached down to her neck. Glowering at Benson she said:

‘Stop moping and tell me about the Limehouse case.’

Her decline had been rapid. Within a week of pulling that cracker, she’d lost weight. Her breathing had turned short. She’d coughed up specks of blood. After ten days’ resistance, a chest infection spreading, she’d said goodbye to her rambling home with its dormant garden and taken a room at the Royal Marsden Hospital.

‘You told me it’s about family secrets,’ she said. ‘I’m intrigued. Especially when they end in death.’

The riddle in the cracker – ‘Why is it getting harder to buy Advent calendars?’ – had foxed Camberley; and Benson had refused to read the punchline. He took her hand:

‘Jorge Menderez is a doctor from Spain.’

‘What kind?’ she snapped.

‘Medical. Works for years in a maternity clinic and then becomes a GP. Decides to take a sabbatical. Comes to London, seeking distance.’

‘From?’

‘Memories. Problems with his parents. Childhood confusion. So when he gets to London he checks out various therapists and finally settles on Karen Lynwood. Like him, she’s in her fifties. And she speaks Spanish.’

‘I assume he spoke English?’

‘Yes. He did his medical training at Cambridge.’

‘Think pilgrimage.’

‘Sorry?’

‘A return to the place that put him on the road to the rest of his life.’

‘Well, it’s an odd pilgrimage, because, according to the police, he never went to the shrine.’

‘Meaning?’

‘He rents a house by Limehouse Cut and just stays there. Never went back to Cambridge – at least not to his college – and made no attempt to contact any of his contemporaries.’

‘Very interesting.’ Camberley had closed her eyes and was frowning; breathing was hard work. ‘Did he know anyone nearby?’

‘No.’

‘Colleagues from Spain?’

‘None of them were in the UK.’

The police investigation had shown that Menderez only made connections with people who’d got some link to his homeland and its culture. And none of them had ever crossed his path before. He’d sought them out, wanting, it seemed, a place to anchor his identity; and, having found them, he’d been at pains to maintain his privacy. He’d dropped into the Instituto Cervantes; he’d attended a few cultural events organised by the British Spanish Society; and he’d eaten fairly often at El Ganso, a Spanish restaurant in South Hackney. The only people who’d got anywhere near him were the chairman of the Limehouse Photography Club, a witness for the prosecution with nothing much to say, and, of course, Karen Lynwood, his therapist. Who had a great deal to say but wouldn’t be saying it. And that, said Benson, was the heart of the case.

‘The Crown says she fell in love with Menderez. And he with her.’

‘There’s evidence of a relationship?’

‘Overwhelming.’

Camberley could no doubt imagine the rest: the husband finds out and, driven to despair, he kills the man who’d exploited the rift in his marriage. She’d seen it many times before.

‘The person I’d most like to have questioned is Dr Menderez,’ said Benson. ‘He came to England with a secret . . .’

Benson felt a flush of sadness. He’d turned, to see Camberley’s head had fallen to one side. She was sleeping, a pained frown upon her face. With each uncertain respiration, a piece of shiny blue plastic moved in a tube at the side of the helmet, rising and falling no more than a centimetre. Benson watched it, holding his breath: up, down, up, down, up, down . . . the blue disc always fluttering at the high and low point . . . up, down, up, down, up, down . . . Unable to watch this quiver on the edge of life, he tiptoed towards the door, but then, just as he was about to leave, he heard a soft cry:

‘Will, come back.’

Benson quickly obeyed, but his mind fled elsewhere. He couldn’t forget the Camberley he’d known since his own strange death, the woman who’d brought him to another life and who, only recently, had sported a crown, worn aslant above a mischievous grin. She’d worked out why it’s getting hard to buy Advent calendars. Their days are numbered.

‘I want to talk about the trial,’ she said hoarsely.

‘We will, Helen. I’ll come when I can, after court, but you’ve got to rest now, there’s no—’

‘Not the Limehouse case, Will. I mean yours . . . your trial.’

‘Mine? That’s dead and buried.’

She shook her head.

‘There are things you must tell me; and there are things I must say.’

Benson had taken her hand once more. They were looking at each other through a shroud of PVC. She was going to die in there. Her skin was sallow and her hair was tangled; but for a moment her pupils became sharp.

‘Our journey’s almost over, Will. And I’ve one last step to take. Help me finish what we began.’

Before Benson could reply, she slowly closed her eyes. All he could hear was the rasp in her lungs and the uneven passage of the plastic disc. Up, down; up, down; up, down . . .

On the way home, Benson popped into a newsagent’s and bought a keyring torch. While the manager rooted in a box for some batteries, Benson heard the news, coming muffled from a radio in a back room. A body had been found in Nine Elms. But Benson couldn’t engage with someone else’s death. He could only think of Camberley, who’d shortly leave him . . . wanting, first, to return to the beginning of their relationship. The apposition of beginnings and ends had thrown him, making that inevitable parting all the more significant. Back on board The Wooden Doll, his barge moored at Seymour Basin, off the Albert Canal, he stood in the darkness, sending a blade of light along the curved walls, oiled floorboards and beamed ceiling. He drew patterns, cutting left and right, slashing at the night; and tears ran down his face like never before, save once, when a screw had told him his mother was dead.

‘Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. It’s been twenty-one years since my last confession.’

‘You must have come with a skip.’

‘No, Father, I’ve come with a mistake.’

‘Well, I hope it’s a corker.’

‘It’s about doubt. The breaking of a promise. And betrayal.’

‘That’s fairly Petrine, actually.’

‘Petrine?’

‘Like Saint Peter. Do you remember? The denial by the fire? He made three mistakes in less than a minute. But, to be fair, he was scared out of his trousers. What about you . . . are you all right?’

‘Yes . . . I’m just tense. And confused. And it’s been such a long time, Father. I can’t remember what comes next.’

‘It’s forgiveness. You can tell me anything. Anything at all.’

Tess de Vere hadn’t planned to enter the confessional. Throughout a wet Sunday, she’d stayed warm at home in Ennismore Gardens Mews reading a trial brief, preparing for tomorrow’s client conference with Benson. Then, to clear her head, she’d ambled through Hyde Park into Marylebone. She’d stared at a display case in Shipton’s, the jeweller’s; and then, not quite thinking, she’d followed her feet into a church off Spanish Place. She’d seen the glow of torchlight on worn-out black Oxfords peeping out from beneath a curtain on one side of the booth. She’d heard a page turn, and then a soft laugh. Moments later she’d been on her knees.

‘As an undergraduate I went on work experience with a solicitor,’ she said suddenly. ‘And I attended the trial of a student charged with murder.’

The priest’s head remained perfectly still. And Tess thought of her father in Galway, motionless in Barna Woods, listening for redwings.

‘This student, a man, went to a pub on a Saturday night. He ended up outside, challenging another man about his behaviour. This other man floored him with a headbutt. That’s it. Only this other man was found dead in a back street forty minutes later.’

Benson had been arrested, because he’d been seen in Soho, and the question of his guilt or innocence had been born.

‘When this man got life, Father, I watched him go down . . . and it was traumatic.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I was powerless. And because he’d sworn to me that he was innocent.’

‘You believed him?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You do.’

Tess closed her eyes and knotted her fingers.

‘He told me he was going to be convicted, he could sense it, but he needed at least one person he didn’t know to accept that he was innocent. He didn’t want pity, Father; he wanted belief . . . and it was like he was giving me his soul, and I had to look after it, because once he was taken away in a prison van his life was over.’

Tess opened her eyes to find the priest had moved closer to the grille.

‘And when you saw him again?’ he said.

‘I felt bound to him. Bound to who he’d been, to who he might have been, and to who he’d become . . . I’d been left with his true identity, only no one accepted him any more, and he didn’t accept himself . . . and he still doesn’t . . . and there was I, holding on to something important that he didn’t want back, because he’d changed . . . It’s complicated, Father.’

‘It could only be complicated.’

Alone in the tense moments before the verdict had been delivered, Benson had told Tess he would have liked to come to the Bar, and she’d thrown back hope like a lifeguard: go for it, she’d said. Don’t give up. Sixteen years later Tess had sat in a restaurant, eavesdropping on two hacks as they mocked the ex-con no-hoper who’d opened his own chambers from an old fishmonger’s in Spitalfields. Clerked by a former cellmate with convictions for tax fraud, he’d landed a murder trial that he couldn’t possibly win.

‘Are you frightened?’ said the priest.

‘Yes, Father.’

He waited.

‘Of yourself?’

‘Yes. Because I don’t know what I feel. The man who came out of prison is so different from the person I’d met in the cells. That guy was simple. He was desperate, but . . . his desperation was transparent.’

‘Which is why you trusted him?’

‘Probably, yes.’

‘What about the man who was freed?’

After leaving that restaurant, Tess had resolved to help the no-hoper defy his critics. She’d parked her classic Mini near Benson’s barge, waiting for him to come home. He’d appeared, head down, checking his pockets for his keys, talking to himself, seconds before a passer-by coughed, gathering mucus in his mouth.

‘Freed?’ she asked. ‘He can’t shut doors, or lock them. He can’t look anyone in the eye. He’s still desperate, but it’s clouded now. He can’t tell you what he feels, because he doesn’t know what he feels. I watched someone spit on him, Father, and he accepted it without complaint. I gave him my handkerchief and he just wiped his face.’

And that had been the beginning. For when Tess had run across the road, she’d no longer been a powerless bystander. She’d been a solicitor with Coker & Dale, a top London firm. Despite opposition from the partners, she’d stayed at Benson’s side. They’d become ‘Benson and de Vere’, with Archie Congreve in the clerk’s chair and Molly Robson on the throne of chambers administration. They’d become a team like no other. The priest drew a deep breath.

‘Isn’t this compassion?’

‘Yes. Only . . . I’m frightened I might love him.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘Nothing. It’s just that . . . I came to doubt him.’

‘What’s wrong with doubt? I graze on the stuff.’

‘I mean serious doubts, Father.’

‘So do I.’ The priest paused, as if to read the label on a packet of laxatives from hell. ‘They clear the mind. Wonderfully. And they lead to action.’

The last time doubt had brought Tess to her knees, she’d been with Fr Kennedy. He’d dished out the penance before Tess had described the wrong turning. He couldn’t restrain a longing to forgive. She said:

‘I tried to deal with these doubts. I asked this man to help me prove his innocence. And he begged me not to.’

‘Did he say why?’

‘He said if everything was resolved he might lose the flame. You see, Father, something takes over when this man walks into a courtroom. His deadened life is left behind . . . he says he comes alive . . . and it’s electrifying. So I promised to leave his past alone.’

‘And is this the mistake that weighs upon you?’

‘No, Father. My mistake was to break that promise.’

‘And why did you break it?’

‘Because in public he says he’s guilty and in private he says he’s innocent . . . and it harms him and his family and the family of the man who was killed. They’re all ghosts in a twilight world of confusion and anger and grief.’

‘So you did what you promised you wouldn’t do?’

‘Yes. Helped by my oldest friend, I began a secret investigation into this man’s trial.’

Urged on by Sally Martindale, Tess had pored over the witness statements, seeking leads that may have been missed. The priest leaned closer.

‘Did you uncover anything?’

‘Yes. And if we act on what we now know – which, for him, would be an act of betrayal – there’s a chance he’ll be vindicated.’

‘You don’t sound especially pleased.’

‘I’m not. Because I’m scared of making a second, bigger mistake. I’m wondering if it might be better for people to live without the truth, because, if the truth comes out, the confusion and anger and grief won’t go away. It’ll only increase. The twilight world will only get darker.’

‘How so?’

‘Someone out there will be arrested, and their life, and the lives of those closest to them, will be changed, utterly and for ever. And as for the man who’s declared innocent . . . what does he gain? He can’t get back the life he once had, and he might lose the one he’s built upon injustice, which helps so many people . . . because he’s different. He listens differently. He acts differently. And all that might disappear . . . because of the truth. Come on, Father. Let’s face reality. The truth? Who needs it?’

The priest leaned back and the light – a gap between the curtain and the booth – fell upon Tess. She squinted, for even weak light is bright in the dark.

‘What have you found?’ said the priest from a shadow.

‘A bracelet.’

‘An investigation?’

‘Yes.’

‘Into Rizla’s trial?’

‘Yes. That’s what I said.’

‘And you’ve found a bangle?’

‘No, a bracelet.’

Archie dropped the sock that he’d been filling with breadcrumbs onto his desk.

‘Take me through this again.’

At that moment the door opened and Molly bustled in, clutching a wicker basket.

‘Stand well back,’ she said. ‘I’ve got the oranges and the sugar. Oh . . . hello Miss de Vere. Is everything all right?’

Archie pointed to the chairs in front of his desk.

‘Miss de Vere has something to tell us.’

Talking about her dilemma in the darkness of a confessional had nudged Tess into a kind of daylight: she had to tell Archie and Molly what she’d been doing. Knowing the two of them had planned to meet in chambers to continue ‘preparations for the next trial’, Tess had gone there, but on entering the clerk’s room she’d found Archie preoccupied, crumbling sliced brown bread into a bowl. Bemused, she’d watched him transfer the crumbs into a sock. But when he’d looked up, mischief in his eyes, she’d blurted out the beginning and end of what she wanted to say. And now, with tea made by Molly, Tess went back to her point of departure. They listened intently, each sitting on the edge of their chair.

‘The man who found Paul Harbeton’s body was a motorcycle despatch rider. A guy called Mickey Lever.’

‘He’s the one who called the police?’ said Archie.

‘Yes. But that’s not all he did.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘He robbed Benson of a line of enquiry that might have led to his acquittal.’

While talking to the emergency operator, Lever had seen something twinkling a few yards from the body: a platinum bracelet with nine small diamonds. Rather than hand it over to the police when they arrived, he’d put it in his pocket.

‘You’re kidding,’ said Archie, squaring up for some sort of backstreet reckoning.

‘I’m not.’

‘What did he do with it?’

‘He gave it to his girlfriend as a present.’

‘And what did she do with it?’

‘She sold it to a shop in Victoria.’

‘Which one?’

‘Evington’s.’

Tess hesitated. Do I tell them I lost faith? That it was Sally who’d carried on the investigation and not me? That it was Sally who’d gone looking for Mickey Lever and found Tracy Patterson, his girlfriend? That it was Sally who’d brought Tess back on board when she’d sensed a breakthrough? No, she couldn’t. Some secrets had to be kept, because neither Archie nor Molly would have understood Tess’s doubts. For them, Benson’s innocence had always been beyond question.

‘Why sell it?’ asked Molly.

‘Because she got married to someone else.’

‘You went to Evington’s?’ said Archie impatiently.

‘Yes.’

‘And?’

‘They’d sold it to an old lady who lived in Pimlico, and yes, I went there. And when I got there, I took photographs of the bracelet. One of them shows who made it.’

‘And who’s that?’

‘R. J. Shipton in Marylebone. And I went there, too.’

This was the jeweller’s before whose empty window Tess had paused earlier that afternoon. A few months earlier, the owner, Anthony Shipton, great-grandson of the founder, had dug out an old ledger. And Tess had taken another photograph, this time of a copperplate entry from 1918.

‘The bracelet was made by a master craftsman, Manny Brewster. The work had been commissioned by Arthur Wingate.’

‘For himself?’

‘No, Archie, for his daughter.’

‘And who’s his daughter, and why the hell would it matter now?’

‘Because this is where it gets interesting. The bracelet was an eighteenth birthday present for Elsie Wingate.’

Archie looked at Molly, and then back at Tess.

‘Who, might I ask, is Elsie Wingate?’

‘The grandmother of Richard Merrington. Who happens to be . . .’

‘The Secretary of State for Justice,’ said Archie under his breath.

Tess didn’t need to say any more. The autopsy on Paul Harbeton had identified a fatal head injury, along with a vertical bruise to the right leg. The prosecution had argued that Benson had attacked Harbeton from behind, with a kick and a blow to the skull. Camberley had countered with an explanation for which there’d been no evidence: that Harbeton had been struck by a car or motorcycle, causing him to fall and strike his head on the kerb.

Molly spoke:

‘Is Elsie your prime suspect?’

‘No, she died when Benson was in nappies. So the question becomes, who might have been wearing her bracelet on the night Paul Harbeton was killed?’

‘Do you know?’

‘Not for sure. But I’ve a good idea. Only I daren’t follow it up.’

‘Why?’

Tess repeated the worries that she’d disclosed to Fr Winsley; but Archie, roused from a trance, seemed to shoulder his way into the confessional.

‘Sure, tons of crap might hit the fan, and Rizla might like feeling guilty, but, sorry, there comes a time when leaving the truth untold becomes wrong. You’ve got to shake things up. Do what’s right. For everyone.’

‘That’s what the priest said.’

‘What priest?’

‘I went to confession.’

‘When?’

‘Earlier today.’

‘But you’ve done nothing wrong.’

‘He said that, too.’

The priest had wondered whether the true mistake was to have promised not to investigate Benson’s conviction, which, given his claim to innocence, was tantamount to leaving a truth untold.

‘So why did you go?’ said Archie.

Tess wasn’t sure. A longing, perhaps, for that

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...