It’s seven minutes to five, and my mom has been in her tight-lipped, jaw-clenched, company’s-coming mode for two hours now, stalking through the house with bleach spray and towels and barking orders at me and Liam. Or, more accurately, to me through Liam—Liam, tell Olivia to pick up the sweaters all over the living room! Tell Olivia I expect the bathroom to be spotless!—because she and I still aren’t speaking to each other directly.

Usually Liam is on my side, but it’s his first time home from school since Christmas and I think in his way he probably missed her. He’s a junior at UCLA, where he lives off campus in a barren, dingy two-bedroom apartment with four other boys from the fellowship he joined freshman year. One of the guys is from the city, the Sunset District (he went to Lowell), and he was coming back for Lunar New Year with his family, too, so he and Liam carpooled on the way up. I’d had this fantasy of flying down to visit him and then us driving back home together, talking the way we used to, and telling him everything. I haven’t told him about Laurel yet, and I don’t know how he’ll take it.

I had asked my mother yesterday, shyly, if I could bring Laurel to dinner tonight. Laurel is the kind of person who cares about every part of your life and also genuinely loves people. She’s delighted by everyone, and she’s heard so much about my family and has been dying to meet them. And I want to show her this part of me, this part of my life. I want the people I love to know her, to see how when I’m with her I feel myself expanding. And since Lunar New Year is my favorite holiday, it just seemed like the right time.

For months, I’d been having anxiety attacks picturing how this conversation would go with my mom. She isn’t as conservative as the rest of her family—she’s divorced, for one thing, and sometimes we have dinner with her high school friend who’s gay—and we don’t go to church nearly as regularly as everyone else does, but I didn’t know what to expect. I guess you always hope. I had realized that somewhere along the way I’d stopped telling her things, and with Liam gone, I felt so alone in the house, and so part of me hoped that maybe this would be the spark of something different. Maybe we could be like Auntie Linda and Evangeline, who always went shopping together and went on boba runs and stayed up late watching TV and giggling together. Evangeline has always told her mom everything.

“She’s, um, really special to me,” I’d said. My palms and temples were sweating. “Actually, she’s kind of—she’s my girlfriend. Um, I’ve realized that actually I’m bisexual, so I like girls also, and Laurel is the person right now that I—she’s—” God, I should’ve prepared this better. “We’ve been dating.”

“And you want her to come to Chinese New Year?” My mother had stared at me as if I’d suggested we just order McDonald’s for the whole meal. “No. Absolutely not. What are you even thinking?”

Something calcified inside me, some knot in my stomach. In retrospect, of course this was how it had gone: Of course she’d jumped right

past what I’d wanted her to know about me, skimming completely over the part where I opened up, and leapt immediately instead to how it would look to the family. How it would affect her careful preparations.

“My cousins bring their girlfriends all the time,” I said, but I could hear the lack of certainty in my voice. I hated myself for that a little bit.

“Olivia, this is the time for family, not the time for—for some kind of political statement. Gong Gong is not doing well and it might be his last Chinese New Year with us.”

“Lunar New Year,” I muttered. You’re supposed to say Lunar New Year to be more inclusive. It’s not like Chinese are the only ones who celebrate it. But my mom always either forgets or just doesn’t care: probably the latter.

“And I don’t know why you think you need to make this political.”

“It has nothing to do with politics, Mom, it’s about—”

“How is this not about politics? Didn’t you just say you were bisexual? If you want to bring a boyfriend, that’s fine, you’re young, but bring a boyfriend. You don’t need to prove something.”

“But I don’t—”

“You know every single one of my siblings is going to disapprove. And your grandparents, absolutely. And what do you expect from everyone? What is it that you want? Some stamp of approval? Just to make a scene?”

Do I want to make a scene? That is literally the last thing I want, have ever wanted. I hate the spotlight. I don’t want everyone staring at me, everyone speculating about what kinds of things I do with my girlfriend, wondering if I’m lusting after every girl I’m friends with. I don’t want quiet or outright disapproval.

But still—but still. I want to be able to talk about Laurel. I want her to meet my cousins, come to one of our game nights or go with me to my little cousins’ soccer and softball games. I want to take pictures of us at

prom and show my grandparents. I want my grandfather to tell her all the stories he knows about the ancestors, those mythical people to whom I owe my existence.

And yes, I want my family’s approval. Is that so wrong? I want my mom to hug me and say she’s happy for me and she’s proud of me. I want them to embrace Laurel. I want them to multiply my joy.

“It’s completely inappropriate to want to monopolize the night like this. A holiday isn’t about one single person. It’s about family.”

We both said more. Mostly we screamed at each other: She called me selfish and said we obviously needed to go to church more, that I needed to pray about this; and I screamed back that she was the selfish one and that maybe I should just live with my dad full-time instead. I said it because I knew it would hurt her, and it did.

After we fought, I locked myself in my room and called Laurel in tears. But she didn’t pick up right away—she was taking a shower, and by the time she called back I had composed myself. I couldn’t tell her about this fight. Instead we talked about a book she was reading and I said it sounded depressing and terrible and then she teased me about how much I always love happy endings, I’m addicted to people’s joy, and we were both laughing and I remembered how I’m the best version of myself when I’m with her, the bravest version, and before I knew what I was doing I told her it would be great if she came to dinner and I’d call her when everyone was there.

She was thrilled. “Oooh, I’ll make a key lime pie!” she said. “Does your family like pie? What should I wear? Do you guys dress up?”

I’d stopped myself from telling her not to do those things, just in case, because otherwise it would be too easy for me to back down. Now I’m committed.

And now here we are; the party is starting. The doorbell rings.

My mother looks directly at me for the first time since our fight.

“Behave yourself,” she says, her voice low, and then she puts on a smile to open the door for her family.

I feel myself wavering immediately as soon as all my relatives come pouring in. We all fuss over my grandfather, who recently underwent chemotherapy for kidney cancer. He looks frail and thin, but happy to be here. There are thirty-eight of us now, four generations living—the five oldest cousins have children of their own. Our family gatherings are like a paean to heteronormativity. Everyone over the age of thirty is married. No one except my mom is divorced; no one is a bachelor. We have bridal showers and baby showers, girls’ trips, men’s golf

games. In our grandparents’ hallway there are two long rows of family wedding portraits: the bride and the groom. It’s part of how we’re so respectable: a sixth-generation Chinese American family, the kind of family where the boys are all Eagle Scouts and the moms all volunteer for the PTA and the dads teach Sunday school at the Chinese Presbyterian Church on Jackson Street, next to where my great-great-grandfather opened his grocery store and three generations worked after school and weekends. I’ve pored over all the photos, listened to my grandparents’ stories. I know the model I was cast in: generations of strong and devoted wives who bore their husbands’ children and scraped together food for their families against all odds, during war and famine and discrimination, in overseas villages I’ve never been to and across the Pacific and in whatever housing here they could find.

Tonight my cousins have brought boyfriends and girlfriends, a few we’ve already embraced and incorporated into all our inside jokes and potlucks, but a few we’re just meeting for the first time: Brandon’s new girlfriend, Aileen; Katie’s new boyfriend, Joe. I watch as they bring them first to my grandparents, who insist on standing up to shake their hands and hug them, exclaim over them. “Where’s your ring?” my grandmother says mischievously, grabbing Aileen’s hand, and Brandon pretends (maybe doesn’t pretend) to be mortified. Brandon is nearly thirty, and everyone’s been gossiping for years about when he’ll finally find a girl and settle down, because that—both the gossip and the straight marriage—is what my family does. Has always done. Katie is twenty-four and has been through a lot of boyfriends, so her bringing Joe isn’t as monumental.

But I want this, too. I want to bring my person to be ogled over and presented to my grandparents. I want the gossip and the good wishes and, someday, the shuffling of the family to make room for one more and all the teasing about what a mistake it was to get married because now we have to be the ones to hand out lai see.

I left my phone upstairs because I can’t bear seeing

what Laurel might be texting me, waiting eagerly at home for me to tell her to come.

I hug my grandparents, put on a smile, say, “Gung hay fat choy!” a million times to everyone as they come in.

“Let’s eat!” my grandpa says. “I’m hungry.”

The house is full, four generations’ worth of voices bouncing off the walls and tile floor. Our kitchen counter has disappeared under all the bowls and dishes and spare rice cookers, and my mom set up folding tables for the overflow and the desserts. Sometimes at my grandparents’ house I like to thumb through their recipes, and it’s a mix of twenty-ingredient lists and painstaking steps for wonton and then things like “1 bottle Yoshida sauce (Costco). Cook for two hours with pork shoulder and ginger” and “spaghetti Bolognese: mix 1 lb ground beef with 1 jar ragu sauce.” Which is to say, basically, food for my family is a free-for-all. Anything goes. Today there’s lap cheung– and shiitake-studded nuo mai fan, a whole steamed fish, an aluminum tray of salt-and-pepper fried chicken from the place our grandparents like in the Richmond, Auntie Michelle’s Chinese chicken salad, a lasagna, gai lan with oyster sauce, one of those bagged salad mixes from Trader Joe’s, a tray of Spam musubi, the crispy roasted potatoes my cousin Evangeline made once and everyone begged for every holiday forever after. On the dessert table there’s a coffee crunch sheet cake in a pink bakery box, Pyrex pans of mochi, Auntie Linda’s two-tone Jell-O made with heavy cream, and a few pie tins of my grandmother’s nian gao, speckled with sesame seeds and topped with bright mandarin oranges with the leaves still on. Someone, probably Auntie Helene, brought a two-pound box of See’s Nuts & Chews, and there’s a tray of Rice Krispie treats and almond cookies and a platter of orange slices.

I put a few of my grandfather’s favorites onto a plate for him, even though it’s not dinnertime just yet, and bring it to where he’s sitting at the table. It’s good to see him eating. When I make my way over to where everyone is crowded around the appetizer table, Uncle Garrett is telling a story about how Auntie Linda was gone for a week on a trip to Palm Springs with her girlfriends and he had to fend for himself, which is how he found himself one night eating spaghetti with mayonnaise and oyster sauce.

“That is vile,” Emma says, wrinkling her nose. Emma is five years older than me—she goes to Davis—and when we were kids that was enough of an age gap that I didn’t know her well on a personal level. “That is literally a hate crime, Uncle.”

“Stop Asian hate,” Micah says, swooping in for the

sushi casserole.

“You know what, though,” Uncle Garrett says, “it wasn’t bad. Kinda creamy. Kinda—”

“No,” Emma says, “please stop. I want to eat tonight.”

Uncle Garrett laughs. He points at Micah with his clam-dip-laden chip. “Micah,” he says, “you gained some weight, huh?” He motions toward his stomach. “What happened, no soccer this year?”

“You can’t say that,” Auntie Helene, my grandfather’s sister, says from across from me. “You’ll turn him anorexic. You can’t tell kids about their weight. Not like in the old days anymore.”

“Yeah, Uncle, instead why don’t you tell us more about how you’re too smart to get any of the vaccines your doctors want you to get,” I say.

“Or just start snoring,” Emma says. “You know we all love listening to that, too.”

Uncle Garrett hoots with laughter. “You kids think doctors know everything. But you ask them—trust me, you ask them—they don’t have answers for you. You just have to think for yourself. That’s the important thing. You kids have to learn to think for yourself instead of just whatever the Facebook or your phone is telling you.”

We all have roles in life. I feel it more strongly in my family than anywhere else I’ve ever been. The problem, I guess, is that I love them. I love the noise and mess and spectacle and chaos they come with. I love that we exist, against all odds, all those ways our ancestors almost didn’t survive. In a big family, everyone waits for those first clear traits to rise to the surface during childhood, and from then on they’re tagged to you for the rest of your life: Jared is clumsy, Emma is bossy, Liam is hotheaded. You’re not yourself, not completely—you’re a part of a larger fabric. I’m okay with that. I love my family. How well can you really know a big group of people, anyway? Maybe it’s not the worst thing to hide behind their image of me.

I can lie to Laurel, maybe—I can tell her I got sick and missed the party. I could tell her no one else brought a significant other after all. I think she’d let me get away with it. She’s not the kind of person to push. She’s the kind of person who wants to believe the best in you.

“You know,” Auntie Linda says to me, using two spoons to lift the spine off the fish, “in Chinese the word for fish is supposed to mean abundance.

So you’re supposed to eat a whole fish for New Year.”

“Oh yeah?” I say. None of us except my grandparents speak any Cantonese, minus a few words and phrases here and there—siu yeh for a late-night snack, ma fan for something troublesome. I look like my dad, who’s white—my family never tires of telling me this—and so I hoard these small phrases as proof of something in my life. Sometimes I feel like I’m cosplaying at being Chinese. When I was in elementary school, we used to have International Day every year and you could dress up and be in the parade to represent your country, and the year when I wore a cheongsam, I overheard one of the other parents hissing to another that I was being culturally appropriative: Does she think it’s just a costume? I’m already different from my family; I feel it every time we’re together.

“Right, Mom?” Auntie Linda says, turning to my grandma, her mother-in-law. “The word for fish?”

“And noodles,” my grandma says. “Noodles for longevity.”

“That’s what Garrett needs,” Auntie Linda says, rolling her eyes. “I can’t get him to go do his checkups. He’ll have to rely on the noodles instead if he has any hope of meeting his great-grandkids someday.”

“When are we getting those great-great-grandkids, huh?” my grandfather says, and then everyone’s talking all at once, and underneath the noise Liam turns to me and says, his voice low, “What’s going on with you and Mom?”

I hesitate. “Um, just fighting about stuff.”

“Yeah, I can see that. What are you fighting about?”

His fellowship at school is very conservative—I’ve looked it up, read their statement of faith: “We affirm that marriage is between one man and one woman, and anything outside of God’s perfect design for marriage is sin.” I imagine losing him. We used to refer to ourselves as Oliviam, so many times that eventually even our parents adopted it. I’ll be dropping Oliviam off at five! Don’t forget I have Oliviam for Christmas Eve this year!

Is it worth it? I imagine telling Laurel no, she isn’t.

“I wanted to bring someone today,” I say finally,

softly.

Liam raises his eyebrows, a huge grin spreading across his face. “Wait, what?” he says loudly. “Do you have a boyfriend?”

“Um. Not exactly, I—”

“A situationship?” Emma says, overhearing. “Is it complicated? Ooh, Olivia, how did you not tell me? Who is he?”

“Olivia’s in a situationship?” Micah says, and the grown-ups turn to look at each other as if to say, What on earth is that?

“No, no,” I say. My face is turning red. “Nothing like that.”

“Does Olivia have her first boyfriend?” Uncle Garrett says. “Finally?”

“Over my dead body,” my mother says, playing her part perfectly. You’d never guess that we were screaming at each other right before this. How did we all get so good at hiding? “Come on, everyone. Let’s pray and eat.”

We all gather in a big circle and hold hands, and Gong Gong prays: “Heavenly Father, thank you for gathering us all here together. We ask that you bless this food and be with us in this new year. In Jesus’s name, amen.”

While everyone’s getting food, I slip upstairs for my phone. Laurel has messaged me: how’s dinner?? I can come anytime, I’m just at home! And a picture of the pie she made. She candied little slices of lime. It must have taken her hours.

No one’s here yet, I write back, and quickly press send. And then immediately I wish I could take it back—because now what, I’ll ask her over and she’ll realize we all ate already and I lied? I turn off my phone. I feel sick.

I didn’t want this to be the kind of thing we lied to each other about. I don’t want it to seem like I’m ashamed of her. She brought me to meet her family right away; her mom had a rainbow bumper sticker on her car, and her parents both introduced themselves to me with their pronouns. It was a little self-satisfied, maybe kind of showy, but they were nice people. I don’t think Laurel would understand my family. They wouldn’t translate for her. I can’t ask her here just for them to reject her.

But maybe if she were here, it would be all right. Maybe it would feel like it does when we go out, just the two of us, how she has this

way of slipping her hand into mine and making it feel like this little cocoon around us, everything else suddenly mattering less.

And also—this is one of the few things I’ve never told her—I’m afraid she’ll leave me if I can’t be brave about this. It’s such a small thing in the grand scheme of things—it’s dinner; it’s my family. My ancestors crossed oceans and carved tunnels from granite mountains; they survived when it didn’t matter if girls lived or died.

I turn my phone back on. Laurel hasn’t responded, which is somehow worse.

I go back downstairs where everyone’s eating. I manage to choke down some sticky rice and laugh along when one of my cousins starts a game of Would You Rather, but I don’t make it twenty minutes. I keep checking my phone––after the seventh or eighth time, Emma teasingly asks me about it—and finally I escape to the bathroom, where I can sit and stare at the phone, willing a message to come in and also dreading it. Liam finds me in there a few minutes later. I forgot to lock the door, and it flies open, almost banging me in the face. He takes one look at me, then closes the door behind him and locks it.

“Whoa whoa whoa,” he says. “What’s happening here?”

I wipe my eyes roughly and try to smile. “Nothing. I’m fine.”

“Yeah, let’s not do this.” He rips some toilet paper off the roll and hands it to me. “Is this about Mom? Or the guy you’re seeing? What’s happening? If he’s making you cry, dump him. It’s not worth it. You need me to talk to him?”

“It’s not like that.”

“What’s it like, then?”

I think about all the ancestors before me, everything they endured. The famine and wars in the old country, the ocean, the inexorable railroad, the burned Chinatowns. How could I even look them in the eye?

“It’s—” I wipe my eyes again. “It’s actually not a guy.”

His expression doesn’t change. “I see.”

But then he doesn’t say anything else. All the muscles in my chest twist into knots. We sit in a heavy silence. Finally Liam clears his throat. “So who is she?”

“Her name is Laurel.”

“Does she go to your school? Or what?”

your grade? ...

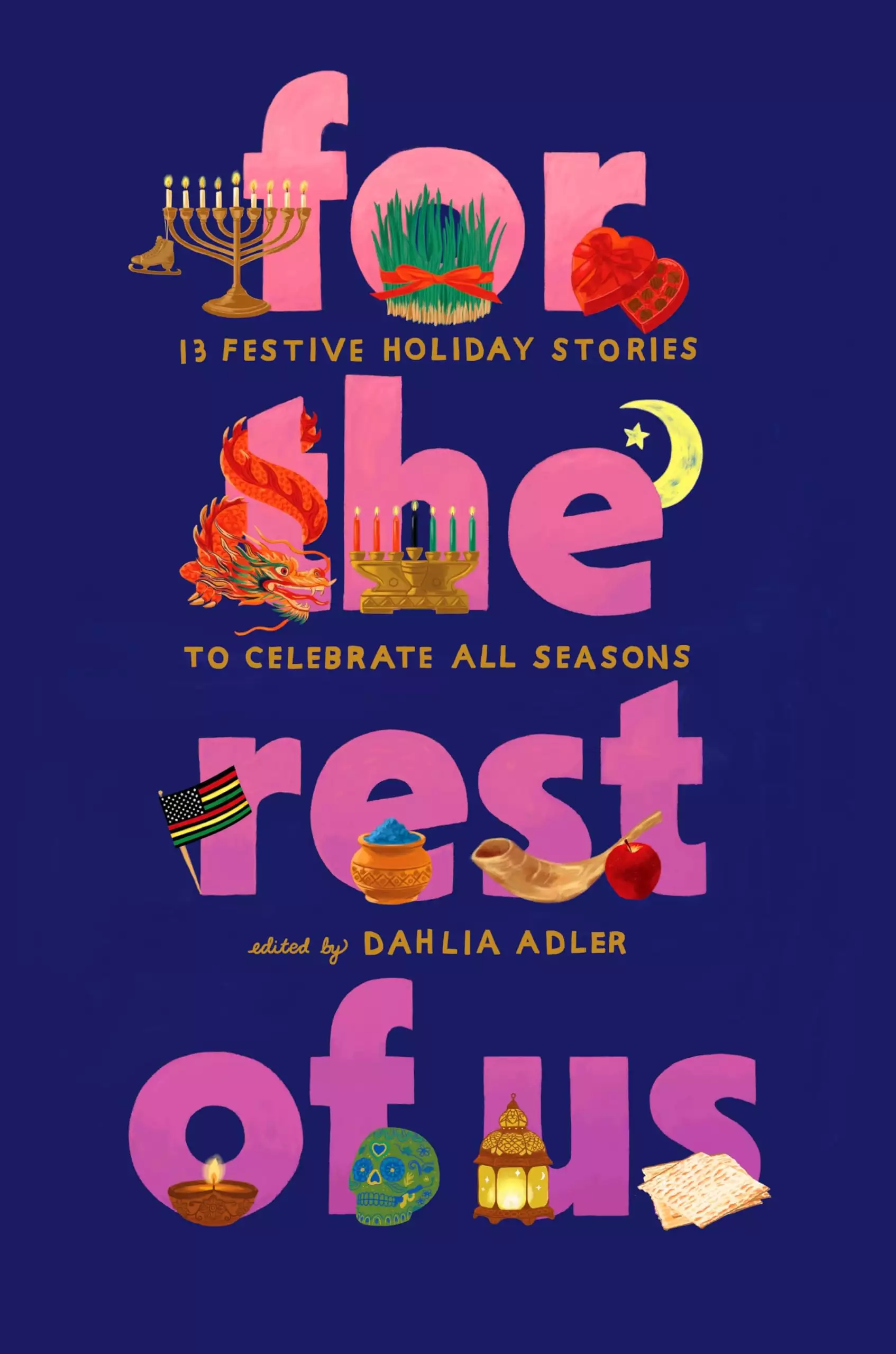

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved