CHAPTER ONE

THERE’S SOMETHING IN THE PAINTING

London is a city haunted by its past, by the cold facts of history and the hot fever dreams of legend. A city built on bones and ghosts, dreams and myths, and all the other things that refuse to be forgotten.

I’m Jack Daimon, and it’s my job to make the past behave.

I walked through a door that appeared out of nowhere, and just like that I was strolling through Westminster late at night, with a map in my head telling me where I needed to be. The pavements seemed more than usually crowded as I headed for the Tate Gallery at Millbrook, and whatever Bad Thing was waiting for me there. It’s my job to defuse the supernatural equivalent of unexploded bombs: all the weird artefacts and infernal devices left behind by forgotten civilisations and peoples we’re better off without. I protect the present, from the sins of times past.

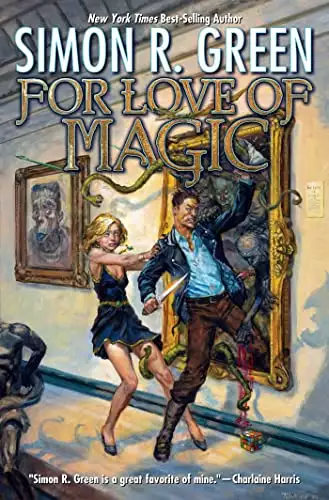

I was wearing my usual black goat’s-skin leather jacket over a black T-shirt, workman’s jeans, and stout walking boots. For me, fashion and style have always been things other people do. I was in my late twenties, in good enough shape, and with the kind of face that doesn’t get noticed. A backpack over my shoulder held the tools of my trade: cold iron and cursed silver, fresh garlic and bottled wolfsbane. A mandrake root with a screaming face, a Hand of Glory made from the severed hand of the last politician to be secretly hanged in England . . . and an athame, a witch knife that can cut through all the things other blades can’t touch.

When I finally got to the Tate, it was closed. All the windows were dark, like so many empty eyes, and two uniformed policemen stood guard at the front door. Even at this late hour a major tourist attraction like the Tate should still have been open for business, but the few hopeful souls who did approach the police were politely but firmly turned away. No visitors, no exceptions, try again tomorrow.

Since I was here, that had to mean whatever had gone wrong was way out of the ordinary and more than usually dangerous. I wasn’t surprised. All art galleries are packed full of things that have been allowed to hang around for far too long. Menaces from the past, preserved in canvas and paint, stone and marble. Just waiting to wake up angry and bite someone’s head off.

I headed straight for the two policemen, and they stood a little straighter despite themselves. Walk like an officer and smile like a predator, and the world will fall over itself to be helpful. I crashed to a halt and looked the policemen over like I was thinking of trading them in for something more efficient.

“Hi, guys! You can relax now; I’ve arrived.”

“I’m afraid the Tate is closed, sir,” the older policeman said carefully. “The lights have failed, and no one can be allowed in until the problem has been dealt with.”

“That’s why I’m here,” I said.

I flashed them one of the many false IDs I’ve accumulated from all the various organisations I’ve helped out. Sometimes they offer me money as a thank you, but I always go for the favour. You get more mileage out of a favour. My Tax Inspector ID opens the most doors, but for the Tate I was a Detective Inspector from New Scotland Yard. One of the policemen quickly unlocked the door, and the other politely offered me a flashlight. I accepted it with a friendly smile, because at the end of the day we’re all just working stiffs, and then I strode into the Tate to poke danger in the eye one more time.

The lobby was dimly illuminated by streetlight falling through the windows like half-hearted spotlights. I pointed my flashlight here and there, but nothing moved in the great open space. The air was still, and the silence was heavy enough to cover a multitude of threats. I did wonder if I might have arrived too late, and missed all the excitement . . . But it didn’t feel that way. Something up ahead was lying in wait, and watching to see what I would do.

I strode on through the Tate, passing quickly through deserted corridors with tall ceilings and pleasantly decorated stone pillars. Important works of art covered the walls, reduced to shades of grey in the obscuring gloom, and there were any number of statues, ancient and modern. I gave them plenty of room. Never trust anything that can stand that still; it’s just waiting for a chance to am

bush you.

I finally rounded a corner and someone else’s flashlight hit me in the face. I stopped, and held up my fake ID. I’m a great believer in being polite and reasonable, right up to the point when it stops working. After that, I have no problem with becoming suddenly violent and completely unreasonable.

A harried-looking dog handler was dragged forward by his Alsatian as it strained against its leash and growled loudly at me. I showed the handler my ID, and he made his dog sit. The animal didn’t want to, but it finally slumped down and glowered at me suspiciously.

“Sorry about that, sir,” said the handler. “We still haven’t found any of the missing people, and the dogs are getting a bit tense.”

“How many teams do you have looking?” I said, as though I understood what we were talking about.

“Six dogs and their handlers, sir. There’s more on the way; we understand this has top priority. Then there’s twenty uniforms from the local stations, and the entire Tate security strength. If the missing visitors are still here, we’ll find them.”

“Who’s in charge of the operation?” I said.

“Some Government type, sir. Wouldn’t even tell us which Department he represents.”

“Did he at least give you a name?”

“Oh yes, sir. George Roberts.”

“Of course,” I said. “It would have to be him.”

I could always trust George to be right in the middle of whatever he was investigating. And if I had to deal with an authority figure, I wasn’t too upset it was him. I knew where I was, with George.

I followed the dog handler’s directions to a large viewing area, and there was George, standing at his ease in a pool of light generated by a circle of battery-powered lamps. He was giving all his attention to two paintings in particular, and didn’t even glance in my direction, though I had no doubt he knew I was there. The young woman at his side fixed me with a challenging glare. I gave her my best Don’t you wish you were somebody? smile, put my flashlight away, and started forward. George finally condescended to turn just enough to nod in my direction.

Well past retirement age, his back was still straight and his gaze was still sharp. Medium height, and rather more than medium weight, George was dark-skinned with close-cropped grey hair, and always wore an Old Etonian tie with his sharp city suit, because wherever he happened to be, he wanted everyone to know he was the man in charge. He didn’t move from in front of the paintings, because he was waiting for me to come and join him, so I did. I like to al

low people their little victories; it makes them so much easier to work with. George showed me his polite smile, the one that means nothing at all because it never touches his eyes.

“So good of you to grace us with your presence, Jack. I can always use another warm body to throw to the wolves.”

I just nodded. “If you’re happy to see me, this must be a really bad one.”

“There are . . . complications.”

As Head of the Department For Uncanny Inquiries, George dealt with the kind of threats most people don’t even know exist. He had power beyond the dreams of politicians, and only abused it when he felt like it. I’ve known George on and off for years. We’re not friends, but we can fake it enough to get the job done.

“I do feel easier for you being here, Jack,” he murmured, as we shook hands just long enough to get it over with. “How much do you know?”

“Only that visitors to the Tate have gone missing, and can’t be found.”

George considered me thoughtfully. “We should work together more often. Your father and I often joined forces, to pull the world’s fat out of the fire.”

“I’m not my father.”

George just nodded. “I sent a wreath to the funeral, on behalf of the Department. I didn’t think it would be in good taste to make a personal appearance.”

I shrugged. “It’s not as if there was a body to bury.” I glanced at the woman standing beside him. “Is this all you brought as backup? You usually travel with enough firepower to intimidate a small nation.”

“We got caught with our pants down on this one,” he admitted. “By the time word reached me on what had happened here, I’d already dispatched most of my forces to the Orkney Islands, to investigate a ring of Standing Stones that had changed their positions overnight. The locals claimed the Stones had been dancing again.”

“Can’t be anything important,” I said. “Or I’d be there, instead of here.”

The young woman at George’s side decided she’d been patient long enough and cleared her throat, loudly and just a bit dangerously. She had an athletic build, a horsey face, and jet black hair. Her power-cut business suit gave her an air of someone ready to walk through anything or anyone who got in her way. I just knew we weren’t going to get along. George nodded politely in her general direction.

“Allow me to present my new second-in-command, Miriam Patterson.”

I gave Miriam my best We don’t have to be enemies; it’s up to you smile. She sniffed loudly, and scowled at George.

“Why has this person been granted access to such a restricted area?”

“Because he’s Jack Daimon, and we need him,” George said patiently.

“What makes him so important?”

“Jack is the current Outsider,” said George.

Miriam studied me carefully, as though she was thinking about buying me and wondering if I’d break easily.

“I always thought the Outsider would be scarier,” she said finally.

“I am,” I said. “When I need to be.” I looked reproachfully at George. “She’s your new second-in-command, and you haven’t briefed her about me?”

“I thought I’d let you give the speech. You do it so much better than I ever could.”

I met Miriam’s icy gaze with my most self-assured smile.

“Think of me as a supernatural troubleshooter, keeping a lid on the leavings of history. It’s my job to deal with the last remnants of a time when Humanity wasn’t even close to being top dog. The old gods may be gone, but some of the things they used to fight their wars got left behind.”

“I don’t believe in the supernatural,” said Miriam.

“It believes in you.”

“The paranormal is just science we don’t properly understand yet!”

“Whatever gets you through the night,” I said diplomatically.

“No squabbling, children,” said George. “Jack, Tate security hit the panic button three hours ago, when twenty-two visitors were reported missing. Surveillance cameras confirm they haven’t left the building, but we can’t find a trace of them anywhere.”

“When did the lights go out?” I said.

“The moment people started leaving the Tate,” said George.

I nodded thoughtfully, because that helps me look like I know what I’m doing.

“Any clues?”

“The only surveillance cameras to stop working were the ones covering this particular area,” said George. “And the only new additions are these two pieces by the Victorian artist Richard Dadd: one quite famous, the other appearing for the very first time.”

“Someone used the Orkneys as a distraction,” said Miriam. “So we’d have no one to send when people started disappearing into the woodwork.”

“Who’d want to piss in your fountain that badly?” I said.

“We police the paranormal,” said George. “We’re never going to be short of enemies.”

I nodded, acknowledging the point, and looked around the open area. I could still feel the Bad Thing watching me, from some unseen hiding place.

“You look spooked, Outsider,” said Miriam. “What do you know that we don’t?”

“Jack doesn’t approve of museums,” said George.

“I have a problem with any place where artefacts from the past are on open display,” I said. “All the spoils of Empire, brought back from the far corners of the Earth . . . not realising how many of them were Trojan Horses. Pots full of poltergeists, weapons looking for a chance

to possess a new owner, and jewels with hidden agendas. The past, forever revenging itself on the present.”

Miriam looked at George. “He does like to make speeches, doesn’t he?”

“You have no idea,” said George.

“And don’t get me started on paintings!” I said, aware my voice was rising and not giving a damn. “Take Rossetti’s ‘The Highgate Lamia.’ He made it look like just another pretty face, but the model who sat for him wasn’t even a little bit human.”

“What was wrong with the painting?” said Miriam.

“If you looked it in the eye, it ate your soul,” said George. “Which is why ‘The Highgate Lamia’ is now a lost masterpiece.” He smiled briefly. “It did burn very prettily.”

“And let’s not forget the Roman statue that walked the British Museum at night, looking for people to strangle with its cold marble hands,” I said. “The trouble with history is that it’s not always content to stay in the past. All ancient artefacts and works of art should be destroyed. Because you can never be sure when they’ll turn on you.”

“And how would we explain that to the general public?” said George.

“If people knew the truth, they’d trust us to do the right thing.”

“The public?” said George. “Have you met them?”

“You’re such a snob, George.”

“Doesn’t mean I’m not right.”

I gave my full attention to the two paintings.

“Do you need me to tell you what they are?” said Miriam.

“The one on the left is ‘The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke,’” I said. “The painter was locked up as a criminal lunatic after he murdered his father. His early works were dainty fairy scenes from Shakespeare: Titania and Bottom reclining at their ease. Chocolate box art. But this . . . is like a view into another world. A whole court of fairies, gathered to observe an event of horrible and irrevocable significance. A turning point in history, that no one remembers any more.”

“Oh come on!” said Miriam. “There’s no such thing as fairies.”

“Don’t tell them that,” said George.

Miriam sniffed loudly. “You’ll be looking under the bed for the bogeyman next.”

“That would be the first place I’d look,” said George. “Provided I had a big enough club.”

I gave George my best thoughtful look. “I’m missing something. You aren’t normally this patient with your subordinates. Why are

you being so nice to this one?”

“Because Miriam has been chosen to succeed me, as the next Head of the Department,” George said calmly.

I took a moment, to consider the implications.

“So she’s a political appointment?”

“Aren’t we all,” said George. “I’m quite looking forward to stepping down. I only hung on this long because I was waiting for someone who could handle the responsibility.”

“And you think she can?”

George shrugged. “Other people seem to think so.”

“What kind of people?”

“None of your business, Outsider,” said Miriam.

I considered her carefully, and she glared right back at me.

“If you don’t believe in the supernatural,” I said, “what do you believe in, that makes you want to run the Department?”

“Protecting people,” said Miriam.

I nodded. It was a good answer.

“Maybe we can work together,” I said. “Try to keep up.”

“I was going to say the same to you,” said Miriam.

We shared a smile, almost despite ourselves, and I turned to the second painting. The title card said simply “The Faerie War.” Two huge armies of elves, going for each other’s throats in an unknown setting. A living hell of inhuman fury and vicious carnage. You could almost hear the screams. Dadd’s style was unmistakable, but this canvas was much bigger than his usual, some twenty feet in length and almost four feet high.

“Where did this come from?” I said, not looking away.

“It was only recently discovered, and donated to the Tate,” said George.

“Like dropping a grenade in a fish pond,” I said. I moved slowly down the length of the painting, trying to make sense of the staggering amount of detail crammed into one moment of battle. “How could Dadd have painted something this big without his keepers noticing?”

“He couldn’t,” George said flatly. “There must have been official collusion at some level.”

Light and Dark elves slaughtered each other on a great volcanic plain, under a sky of roiling purple. The sun was a fierce white furnace. The Light elves leapt and pounced in their intricately carved bone armour, while the Dark elves were more like jungle cats, malicious and deadly in their armour of jade and coral. Swords and axes burned brightly as they rose and fell, while blood ran in rivers across the broken ground.

“That is not our world,” I said finally. “The Fae had to go somewhere else to fight their war, because they knew it would tear the Earth apart.”

“You think we’re looking at something that actually happened?” said Miriam. “The one thing we can be sure of in this case is that Richard Dadd was barking mad!”

“Sometimes madness helps you see things more clearly,” I said.

“I have sent for special equipment,” said George. “So we can take a look at what’s going on beneath the surface of the painting.”

“If you think that will help,” I said.

“Why wouldn’t it?” said Miriam.

She sounded honestly interested, so I kept my voice calm and reasonable.

“Because science can only take you so far. After that you need people like me. Or possibly Weird Harald.”

“Who the hell is Weird Harald?” said Miriam.

George made a quiet embarrassed noise. “A consultant, attached to the Department. Very good at learning secrets by the laying on of hands. Unfortunately, he can’t turn it off. Which is why he spends so much of his time in a straitjacket, in the most secure mental institution we could find.”

“How long before you could get him here?” I said.

George concentrated on the painting, so he wouldn’t have to look at me. “Harald is currently doped to the eyeballs on industrial-strength mood-stabilisers, and chained to the wall of his cell. He was presented with something unusual from a prehistoric burial mound . . . and by the time they could drag him down, he’d killed thirty-seven people just by looking at them. We have exorcists working in eight-hour shifts, but it’ll still be some time before we can make use of him again.”

I just nodded. I’d heard worse. “And you think this painting is connected to the missing people . . ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved