MADELINE

Madeline swam toward the light like her life depended on it.

She tucked her knees to her chest and rolled through the final turn of her 100-meter butterfly sprint. A hard kick off the wall and she was flying, both arms cutting through the cool water in tandem. One stroke, one breath. One stroke, one breath. The pattern was grueling. Comforting. A structured dance of strength and coordination.

One stroke, one breath.

She pulled her chin to her chest as she stretched her body, eyes dropping to the straight black line on the bottom of the pool marking her lane.

With a blink, the line softened. Spread. Black bled across the bottom of the pool, forming the shape of a cave. Its jagged entrance widened, the water shifting to pull her down.

She flinched out of position. Her right hand scraped against the plastic ring of a floating lane line, snapping her attention to the surface. When she looked back down the cave was gone and only a clean, dark stripe remained.

Focus.

She pushed her muscles to the brink of failure, and with one last burst of effort she jammed her fingers against a touchpad. Her time froze in bright red: 1.02 minutes.

Pathetic.

Gulping breaths, she pulled off her goggles and threw them onto the cement deck next to her keys and the pool entry card Coach K had given her after she’d won regionals sophomore year. She’d been fifteen then, two years younger and weaker than she was now, but pulling faster times.

Her legs pedaled slowly through the water as she gasped for breath. The blue surface of the pool glowed against her brown skin, the only light coming from the locker room behind the starting blocks above her. Sweat and chlorine brought a familiar sting to her eyes. She prodded her braids beneath her cap. Then, tilting her head back to stare up at the white backstroke flags, she floated until her pulse slowed.

The sickness inside her didn’t settle.

One more. One more 100-meter, and she’d be too worn out to feel it. Then she’d be able to drag herself home, to lie in bed without seeing the cave behind her eyelids, and sleep.

Movement on the opposite side of the pool caught her eye. She twisted toward it, but the light from the nearby locker room only reached halfway across the water. The pool seemed to go on endlessly into a long, dark night.

“Hello?” she called. It was after nine. No one else should have been here. Even the janitors had left hours ago.

She squinted, but saw nothing.

Another shift in the shadows, and a boy stood at the far end of the pool.

Madeline bit back a scream.

“Who’s there?”

No answer.

The paleness of the boy’s skin was bright against his dark shorts. He was soaked, dripping, his face obscured by wet, black hair. The dim light made him look grainy, like an old photograph.

“The pool’s closed,” Madeline tried. “You shouldn’t be here.” Certain privileges came with being the best, and they weren’t extended to everyone.

“You shouldn’t be here,” the boy repeated.

“This isn’t funny.” She hated the rising pitch of her voice. Her teammates were just trying to scare her. This was just a prank, like how they’d replaced her racing suit in her bag with a pink string bikini at the holiday invitational and she’d nearly missed the first heat, or the time they’d written “blow Coach K” on her weekly training schedule.

But it didn’t feel like a prank. Adrenaline poured through her veins.

The boy stared at the water, frozen. Statue still. The steam from the pool rose around his sharply cut shins and calves. His chest was so pale it took on a reflection of the water, glowing a light blue.

“Fine,” Madeline said, her voice hollow. She twisted and placed her hands on the side of the pool, ready to push herself out.

“Maddy.”

Madeline’s stomach filled with lead. She turned back slowly, squinting through the steam, to see the boy step to the edge of the pool. His gait was strange—his legs and arms bent like he had too many joints.

Cold filled her. Even in the dim light she registered his concave chest and rib lines. He was too skinny to be a swimmer. Skin and bone.

“Maddy,” the boy said, louder now. “Maddy.”

Her fingers gripped the gritty cement of the deck.

“Mad—”

“Stop!” She needed to get out—to run. Instead, she sank deeper into the water, as if it might protect her.

“Why’d you do it?” he asked. “Why’d you leave me in the dark?”

Her lips parted on a sharp inhale. “Ian?”

Impossible. Ian was dead.

But when she looked at the boy on the edge of the pool, she saw him. His long limbs, his mess of dark hair. His memory took shape before her. Wild-eyed. Forever thirteen.

“Ian,” he repeated, and then he gave a shrill laugh that cut off as quickly as it had started. “By dawn, there will be no more Ian.”

“No.” She shook her head. Ian was dead. This was a prank. A hallucination. Maybe she was dreaming. Another nightmare.

Dizziness had her hand slipping off the side of the pool. She fixed her grip.

This wasn’t real.

“Finish the game,” the boy who couldn’t be Ian said.

She shook her head, water sluicing from her cap as she tried to push the images he’d conjured back into the locked box in her brain. Cards, painted with symbols they’d acted out like charades. The cave, punched into the riverside. The moments before the end, when everything had felt right.

“You’re not real,” she whispered. She knew what today was. She’d felt it coming all week, a storm on the horizon. The brain did strange things in response to the anniversary of trauma. A coping mechanism—that’s what this was.

A splash. The boy went under, the water flattening instantly over him. Not a ripple moved the glassy surface.

Terror jolted through Madeline. She pushed out of the pool and spun, peering down into the water. No one swam beneath the surface. No dark shapes. No waves or bubbles.

Ian wasn’t in the pool. Ian wasn’t there at all.

A breath huffed from her lips. She didn’t notice that the humid air had begun to cool until goose bumps covered her arms and legs, and her shuddering breath made a puff of steam.

At the far end of the pool, the water began churning in a spiral motion, as if it were being drained. Then something at the bottom bolted toward her, its wake rippling the surface like an accusing arrow.

She scrambled back, just barely grabbing her keys, and ran.

EMERSON

Emerson was going to beat level twenty-one if it killed her.

She was on hour thirteen in the shadowlands of Assassin 0, her favorite metal album playing on a loop through her computer’s speakers. She’d finally beaten the fire sorcerer and narrowly avoided the Choke—a poisonous cloud that grew with every player it consumed—and was now in a race against a three-legged orc called N00bki11er87 (Had they made up that handle themselves? Must have taken hours…) to get the final poison stone at the top of the twisted tower.

A clatter erupted in her right earpiece and she flinched reactively. Spinning the viewfinder, she caught a flash of a smooth snakeskin head ducking behind the crumbled brick of an arrow slit.

“Nice try.” Emerson activated her weapon wheel and swapped her wrench for her flamethrower. Her loadout had a throwing knife that worked well against orcs, but she liked to watch things burn. Before she could use it, N00bki11er87 leapt out, peppering the room with arrows from their crossbow.

“Shit!” Emerson dropped her soldier to the floor and sent a spray of fire across the room. The orc went up in flames.

And that was why you didn’t bring a crossbow to a flamethrower fight.

She hardly had a moment to celebrate. Within seconds, the mossy avatar started decomposing into the Choke’s green mist. Urgency pumped through Emerson’s blood in time with the bass straining through her shitty speakers. Her player climbed the spiral stone stairs two at a time. At the top floor she flung the door open, but the dark room before her was overrun by a wave of thick, emerald fog, and with a gasp she pedaled backward.

“Are you seriously going to let her stay in there?” Her mom’s voice cut through the music and the heavy sigh of the Choke, drawing Emerson’s shoulder blades together. Their two-story condo was narrow and, with the original wood flooring, sound travelled. She was probably in the kitchen, just below Emerson’s bedroom.

“What do you want me to do, Hannah?” Her dad sounded tired.

He was always tired.

She reached toward her keyboard, covered with greasy fingerprints and chip crumbs, and tried to crank up the album’s volume, but it was already maxed out.

“She won’t eat any real food. She won’t even look at me,” her mom railed on as a second moan came from behind Emerson. She spun her viewfinder, focusing on the fog creeping around the turn in the steps.

“No no no no no.” Emerson pounded the controller as she twisted past it, leaping down the stairs to the landing. This was her last chance to get the poison stone.

“Is this how it is now?” her mom asked. “She comes and goes as she pleases. Doesn’t even go to school?”

“She said she’d take the GED.”

“She said that last year.”

Emerson gritted her teeth.

The distraction cost her. The mist shifted, surrounding her on a rugged exhale. She couldn’t jump free—her avatar began to writhe and screech, and her health on the bottom corner of the screen plummeted.

Before Emerson could take another breath, the bloodred letters FARE THEE WELL, ASSASSIN splattered across the screen.

“Dammit!” She hurled the controller onto her desk, where it collided with a half-empty box of Corn Pops. Her head fell against the back of the chair, neck aching from staring at the screen. Her fingers had locked more than a dozen times in the last hour alone.

She ran a hand over her freshly buzzed hair, the soft prickle tickling her palm. The clock in the corner of her monitor read 10:43 PM.

Maybe she should restart.

Maybe she should eat something first.

She stood and stretched, the reflection of her white skin ghostly as her tired eyes stared back from the window over her desk. She peered through her own image, to the drawn curtains of the apartments across Foxtail Avenue, then two blocks down to the left, where, at Washington Park, heavily armed cops were trying to intimidate another wave of peaceful protesters. People like her dad, who actually thought their speeches and marching made a difference in a good old boys’ town like Cincinnati. To the left, a yellow glow came from the late-night coffee shop on the corner. It had been good once, before gentrification had priced out the old owners. Now it was filled with hipsters, drinking eight dollars’ worth of coffee-flavored milk.

“Don’t you have anything better to do?” she muttered as if they could hear.

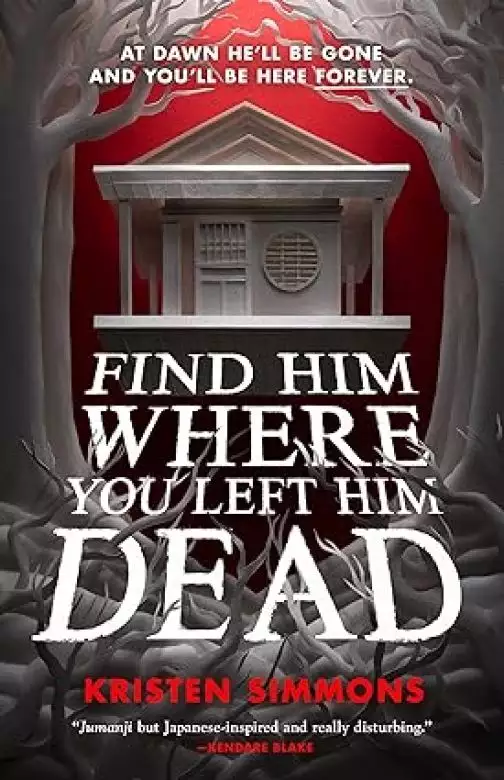

Copyright © 2023 by Kristen Simmons

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved