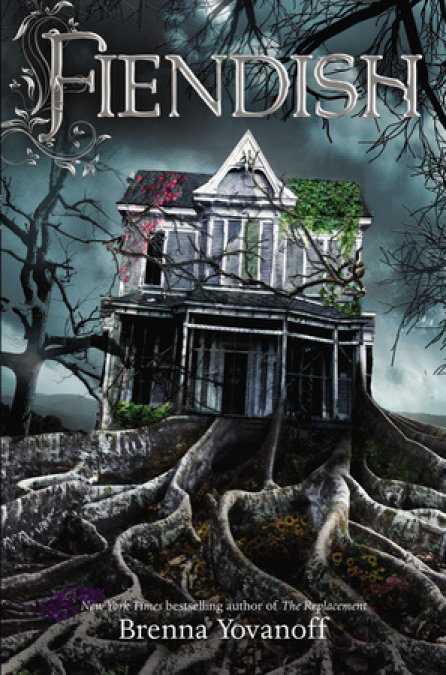

Fiendish

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Clementine DeVore spent ten years trapped in a cellar, pinned down by willow roots, silenced and forgotten. Now she’s out and determined to uncover who put her in that cellar and why.

When Clementine was a child, dangerous and inexplicable things started happening in New South Bend. The townsfolk blamed the fiendish people out in the Willows and burned their homes to the ground. But magic kept Clementine alive, walled up in the cellar for ten years, until a boy named Fisher set her free.

Back in the world, Clementine sets out to discover what happened all those years ago. But the truth gets muddled in her dangerous attraction to Fisher, the politics of New South Bend, and the Hollow, a fickle and terrifying place that seems increasingly temperamental ever since Clementine reemerged.

Release date: August 14, 2014

Publisher: Razorbill

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Fiendish

Brenna Yovanoff

THE LAST DAY

When I was little, everything twinkled. Trees and clouds all seemed to shine around the edges. At night, the stars were long tails of light, smeared across the sky like paint. The whole county glowed.

Back then, my life was mostly pieces—tire swings and lemonade, dogwood petals drifting down and going brown in the grass. Cotton dresses, bedsheets flapping on the line. An acre of front porch. A year of hopscotch rhymes.

On the hottest days, I kicked off my shoes and ran out to the middle of the low-water bridge. The air was warm and buzzing. The creek raced along under me, bright as broken glass.

I jumped rope with my cousin, who was older and shiny. Shiny like an opal ring or a ballerina, and Shiny because it was her name. She hooked her pinky in mine and swore how when we were old enough, we’d run away from Hoax County and live in a silver camper on a beach somewhere. We’d be best friends forever.

Later, when everything went dark, I tried to think how the bad thing had started, but the pieces wouldn’t come. No matter how I walked myself back through that last day, there was always a point where time stopped. A sheet seemed to loom in my mind, and no matter how I pressed my nose against it, I couldn’t see past.

There were things I knew. I knew my mama had been making skillet chicken for dinner, because I remembered running out to the garden to pull some onions for the gravy, and how when I crawled down through the vegetable patch, the place under the tomatoes smelled like hay. It was warm and sweet, and for a while, I just sat smelling it, singing the first line of “Farmer in the Dell” over and over because I couldn’t remember the rest, and counting my numbers.

The vine above me had four little tomatoes all hanging in a row, and in the middle, there was a fifth one. It was like the others, except not. Because instead of silkworm green, the fifth was gray—heavy as an elephant and made of stone, growing in the garden like a living thing, and I laughed because it was a miracle.

I was too little to think a miracle could be anything but good.

Later, it seemed that the whole world began and ended with that tomato. Not with the voices of men, or the way every room in the house got hot. But with that one stone marvel in the garden. With the clean white sheet in my head, and a silver needle pinched between someone’s fingers. Hands that reached to close my eyes and a whisper like a spell. Hold still and sleep. Wait till someone comes for you.

But no one came.

In the canning closet, the air got hard to breathe. Jars broke open. Cherries splashed my face and arms, hissing on the bricks, but if it was hot, I couldn’t feel it.

Then everything got quiet and that was worse. The shouting stopped and the fire burned out. I thought I might be the only person left in the world.

Before, I’d never been scared—not of deep water or falling off the swing set, or any of the other things that kids from town cried about. And never of the dark.

Dark was my best time. In summer, when the sun went down and the moths flapped against the screen, I sat in my mama’s lap on the back porch, looking out at the tupelo trees, wearing my blue-fairy nightgown and holding my flannel bear. Mama wound the key in its back and sang along—Oh my darling, oh my darling.

Sometimes it doesn’t matter how dark the world gets. You can be saved by the smallest thing. I played the Clementine song, turning the key again and again, winding up the memory of her voice until the music turned slow and jangly and the flannel bear wore out like a sock.

The closet was in the back corner of the cellar, and I had never liked to go down there. The floor was made of concrete and the air smelled swampy. Spiders lived behind the closet door and in the cracks between the shelves.

Now it was the only place in the whole world I was even really sure of.

The farm where we lived was on a shallow little branch of the Blue Jack Creek, and the water fed the stands of willow trees that grew around the house. Before, my mama had always kept them in their place, but now they stretched out, reaching in the dirt. They pushed until the wall caved in. Roots grew over my body.

The shoulders of my nightgown let go and my elbows poked through the sleeves. My hair got long, snapping its rubber bands. Sometimes I could feel my bones growing.

Every little stitch and seam told me I was changing, leaving behind my old, baby self, but when I tried to think how I must look, the picture wouldn’t come. The more I tried to see it, the harder it was to see anything but that white sheet, and then the voice would rise up in my ear, getting louder, echoing around me. Hold still and sleep.

It was easier to turn toward it, to follow it down into a jumble of dreams—hills and creeks and hollows. Trees to climb, fields going on forever.

I fell headfirst into a sinkhole of pretty things, and the world inside your eyelids is just as big as the one outside.

THE GIRL IN THE CELLAR

The voices came from a long way off, and at first, they didn’t mean anything. They were just mutters in some broke-down cellar, and I had long since stopped being Clementine in the canning closet.

In my dreams, I was Clementine running through the grass. I was alone, or else with a boy. I couldn’t see his face, but I knew him from some other time, or maybe I’d only just invented him. We raced across an open meadow, toward a tree covered in blue and purple flowers, which meant it wasn’t real, but I ran to it anyway.

Or I might have been someplace else. Maybe sitting in my own living room, listening to the TV and stitching pictures on a quilt square with my mama’s embroidery thread, or standing on a lawn somewhere, watching crowds and colored lights—a party of white tablecloths and paper lanterns. I just couldn’t remember if it was a place I’d been to once, or a life happening far away, or something I was only now making up. I’d been living on dreams so long it was hard to know if any one of the fifteen things happening inside my head was real.

Then someone spoke, closer than any of the ghost-people at the party, than any of the voices in my dreams.

Nothing down here but dry rot and trash.

A boy’s voice, with an accent thicker than was common for Hoax County. Almost thick enough to cut.

He sounded bored with the trash and with the dry rot. Bored with the whole business—maybe even with himself—and hoarse like he’d been shouting.

Also, though, he sounded real.

In the moldy dark of the closet, I opened my mouth. The sheet and the sharp, warning voice were there at once, ordering me quiet, saying wait and sleep, but I’d already been waiting for so long. I was done with that. On the other side of the door were real people and I was going to make them hear me.

I tried to shout, but it was no good. My throat was too dry to make words. My arms wouldn’t move to pound on the wall. I stood in the dark, with roots tangled in my hair, bits of glass sticking to my skin, still holding the windup bear. The flannel was squishy with groundwater, and I squeezed hard, digging my fingers into the clockwork. The song came whining out, broken from how many times I’d played it. It only clanked one line, Oh my darling, oh my darling, before grinding to a stop.

I could hear feet kicking around through junk and broken glass, too many to be just one person. Then they stopped, and the whole place got so still it hurt my ears.

The breathless silence went on so long I thought I would nearly go crazy, and then the first boy spoke again, close to the wall. “Did you hear that?”

Someone answered from farther off, and I could hear the way the words rode up and down, saying no. Saying what are you talking about and I don’t hear anything and let’s leave, let’s leave.

The roots had all grown over me, twisting around my arms and between my fingers, and the sweetest sound in my life was the ripping noise when I pulled my wrist free.

I wrenched the bear’s key a half turn, a full turn. Then the clockwork caught, singing out its broken song, tinkling in the dark.

Oh my darling Clementine, thou art lost and gone forever, dreadful sorry Clementine.

And I waited.

“I’m telling you,” said the first voice, close to the wall. “There’s something in there.”

Yes. Yes, there’s something—here, I’m here. Please come find me, I’m here!

But no one answered. I could feel myself sinking, running out of hope. Already half-willing to let go, to fall straight back down into dreams.

Then came the dry shush-shush of someone running their hands over the wall, feeling along the bricks.

“Check this out. I think there used to be a door. Here—Cody, help me get it clear.”

There was a scraping noise like chalk on a driveway, and I told myself it wasn’t how it sounded, it wasn’t someone pulling out the bricks, because if I let myself believe in rescue and it turned out I was wrong, I would sink right down in the cold black dirt and die of the despair.

But the scraping got louder. The voice in my ear had stopped telling me to wait.

There was a crash, a burst of light against my eyelids, and the bricks fell away in a storm of noise and dust. My heart beat harder, and now he was in the canning closet with me.

“Oh my God,” he said, and then his hands were on mine, so warm they nearly hurt. He grabbed my wrists, peeling back the willow roots, yanking so hard my whole body jerked.

I tried to help him, but I could barely move. He was touching my face, steadying my head as he unwound the roots in my hair, tearing me away from the wall.

Then I was falling. I knew I should catch myself, but my bones felt loose and unstrung. It had been an age since I’d taken a single step, and my legs wouldn’t move. My eyes wouldn’t open.

“Jesus,” he said, catching me around the waist. “Would one of you help me? Get her arms!”

No one came to get my arms, though, and he dragged me out himself. I could smell his shirt and his hair, like leaves and summer and fresh air.

He went stumbling back with his arms around me and we fell hard on the floor. The bump when we landed seemed to knock something loose. My fingers spread wide and then made fists. My arms and legs began to tingle. When I turned my head, he seemed to glow against my eyelids, and I knew he must be the hero of the story, just like in all the books.

This is ever-after, I thought. This is the happily, the end. This is the prince who saved me.

I lay in his lap with his knees digging into my back and waited for him to kiss me and break the spell. Instead, he scraped his thumb across my mouth, wiping away the dirt. The rush of fresh air was almost too much to take. I coughed on it, trying to remember how to breathe without choking.

“Holy hell,” someone said from over in the corner. “Holy everloving hell. Fisher, what have you done?”

He said it loud and quick, sounding so scared that for a second, I was sure they’d leave me there, lying in the cellar with all the bricks and broken glass.

“Give me your shirt,” was all Fisher said.

“Are you crazy?” said one of the other boys. I thought there were two, but their voices were enough alike I couldn’t tell them apart. “I’m not messing with that. You do it, Luke.”

“No way I’m letting anything of mine touch anything like her. Fisher, you don’t know what she is.”

Fisher didn’t answer, but there was a shuffling noise above me and this time when he touched my face, it was with a wadded-up cloth. It felt like cotton, warm from the sun, and it smelled like him.

“Who are you?” he said. When he leaned down, I could see him printed on the inside of my eyelids, a bright mess of colors like a paint splotch in the shape of a person. “How did you get here?”

I tried to answer, but my voice felt ruined. I wanted to tell him that I was Clementine DeVore and he was scrubbing my face too hard and this was my cellar and my memory was a clean white sheet and what was he doing here in my cellar, but all that came out was a sigh.

One of his friends spoke then, slow and soft. “Fisher, this is just too freaky.”

“I know,” he said, holding my face between his hands.

“Well, how do you know she ain’t some creep down-hollow?”

Fisher crouched over me, still scrubbing my forehead and my cheeks. “I don’t, so just shut up. God, look at all this soot.”

I tried to turn my head, but he had his palms pressed hard against my cheeks. The shape of him was a warm blur on the inside of my eyes, twinkling with gold.

“Hold still,” he said. “You have to hold still. There’s busted glass everywhere.”

“Look at her eyes,” said one of the other boys under his breath. “If that’s no fiend, I don’t know what is.”

The word was ugly, and the way he said it was worse.

“I’m not deaf,” I said, and my voice was dry and scratchy, more grown-up than the one I remembered, but it was mine. “And I don’t know how your mother raised you, but mine taught me it was rude to go throwing around a word like fiend.”

The three of them got very quiet. I could feel their stillness in the air, the way they had all stopped breathing.

Then Fisher laughed, a short, barking laugh. “Looks like she’s got more manners than you, whatever she is.”

He turned away from me, like he might be about to stand, and when he did, the light around him faded.

“No,” I said, before I could even think about it. “Don’t go. Come back where I can see you.”

“You can’t see me,” Fisher said. “Your eyes are shut.”

But he leaned closer, putting his shirt against my face again, and in one long breath, I was nearly swallowed up by all the things I’d lost. I remembered days spent laughing in the knotweed down by the creek, nights out in the fields and the woods, skimming through the long grass like a ghost, a blanket spread over the ground and Shiny, my Shiny, with her fast, flashy laugh and her finger hooked through mine.

“You smell like a picnic,” I said, struck again by how strange my voice was—like a picture doubling over itself.

“And you smell like mildew.” His voice was rough, but for just a second, I thought I could hear him trying not to smile.

He was checking the lace at the edges of my nightgown, sliding his fingers along the insides of my cuffs. He pulled the collar away from my neck, following it around until he found a lumpy knot of cloth that had been pinned there since the world went dark, a strange weight against my collarbone.

“What are you doing?” I whispered, but he didn’t answer until one of the other boys said it too, sounding small and scared.

“What is that? What’s she got around her neck?”

Fisher tugged at my collar, unfastening the knot. “I don’t know, but it looks like one hell of a trickbag.”

The third boy spoke from farther off, and if I’d thought he sounded scared before, it was nothing compared to how his voice wavered and cracked now. “Then don’t mess with it. You don’t know what kind of craft is on that thing.”

Fisher laughed that short, dog-bark laugh again and put the twist of cloth into my hand, closing my fingers around it. “The kind that can keep a girl shut up in a basement for God knows how long, and she lives.”

“Shit, Fisher! Just—what are we going to do?”

“I’m taking her down to the Blackwood place.”

Right away, the other two began to argue, talking over each other. “No, no way. You can’t go messing with hexers and fiends. It’s no business of Myloria Blackwood’s that we found some crooked girl down in some burned-out house.”

Fisher slid his hands underneath my back. “It’s Myloria’s sister that lived out here, and by my count, that makes it her business. So I’m taking this one down there, and if you’re going to help, then help. If you’re not, you can find your own way home.”

Without another word, he scooped me up, one arm hooked at my knees and the other around my waist. When he lifted me, the shoulder of my nightgown split wider. The air felt damp and cool against my skin.

“Here,” he said, jostling me higher against his chest. “Grab on around my neck.”

“Why don’t they like me?” I whispered, getting my arms up, feeling around for his shoulder. “What’s wrong with me? I never did anything to anyone.”

Fisher was quiet for a second and when he answered, he sounded strange.

“It’s not your fault,” he said. “They’re just nervous about how your eyes are sewed shut.”

THE BLACKWOOD HOUSE

Fisher carried me out of the cellar.

At first, I was so overcome by the rush of sunlight and good air that it was hard to think of much. But even as Fisher reached the top of the stairs and stepped down into the yard, my wonderment was fading and I needed, more than anything, to look around.

I wanted to see the pastures behind the house, speckled blue with morning glories, and my special corner of the garden where I was allowed to dig, and the tupelo tree that shaded the porch, and if the little green birdhouse I’d painted to look like our own house was still hanging in its branches.

I tried again and again to open my eyes, and the harder I tried, the more decidedly I knew that Fisher had been telling me the truth.

“Well, that’s a vexing thing,” I said, and I’d meant it to sound brave, but all that came out was a whisper. “They really are sewed shut.”

“I think once the thread’s out, they’ll be fine,” he told me, but he was quiet a minute before he said it. The way he stopped to pick his words only made me sure that things were very bad. “You’ll be fine. Just hang on. I’m taking you to someone who can figure out who you are and where you come from.”

I wanted to tell him it wasn’t that complicated, that I came from the cellar, from right where he’d found me. That this was my home.

“My aunt Myloria,” was all I said. “That’s what you mean. You’re taking me to Myloria Blackwood.”

He didn’t answer, but hitched me higher in his arms and walked a little faster.

The only way I knew what direction we were headed was by the sun on my face—the patches of shade as we moved in and out of the sycamore trees that grew along the ditch. I could tell by the crunch of his boots that the driveway out to the main road was grown over with weeds.

His arms were warm and he held me tight enough that I could feel him breathing. My face was against his shoulder and he hadn’t put his shirt back on. His skin was slick against my cheek, and even when my neck started to hurt, part of me was perfectly fine to keep smelling the warm, dusty smell of him.

But there was another part that wanted to get down. The way his arm moved when he walked was rubbing the side of my face. My legs ached now. My feet were tingling like they’d been crammed into church shoes for too long.

When we finally stopped, Fisher bent and laid me down on something metal. It was smooth as a piece of hard candy, warm from the sun. I felt around for the edges with my fingertips and understood that I was lying across the hood of a car.

I could hear him nearby, crunching around in the weeds, jingling keys and opening doors. Then he scooped me back up and arranged me in the passenger seat.

As soon as he’d dropped down in the driver’s seat, there was a low rumble, coughing and snarling, getting louder. The engine roared and we lurched forward, then the whole world seemed to fall away and there was only the wind, whipping by with fantastic speed, tearing at my hair. Almost too much air to breathe.

The drive took a long time, or else no time at all. The darkness of the canning closet had made me confused about things like time, like I couldn’t feel it passing or count the minutes anymore.

When Fisher parked and hauled me out of the car, I tried to tell myself that I only liked the feel of him because it was so good to not be walled up in a canning closet, but it was other things, too. He smelled like green and sun and goodness, and there was plenty to like about the way his shoulder fit against the side of my face.

Then he was jostling me higher, pounding on someone’s door.

We’d been waiting long enough for Fisher to start shifting his weight from foot to foot when a voice spoke from somewhere deep inside the house, sweet and strange and familiar. “Who is it?”

“Eric Fisher, ma’am. I’ve got something that you’re going to want to see.”

For a moment, there was nothing. Then the voice called back, “Come on in.”

As soon as Fisher stepped inside, the light behind my eyes got darker. His boots echoed on the floorboards as he made his way through the house, and then someone else was with us.

Her footsteps were light, and she smelled like roses and mint and the warm, dusty smell of attics. “Oh, my word.”

For a second, no one said anything else.

Then the woman let out a long breath and stepped closer. “Who is that?” she said. “What happened to her eyes?”

“Don’t know, but I’m pretty sure she belongs to you. Me and the Maddox boys found her down in the DeVore house. Is there someplace I should set her?”

For one strange second, the woman seemed to disappear. No movement or breath, no sound at all.

Then she spoke from across the room, loud and shrill. “And you saw fit to bring her here?”

Fisher stepped farther into the room and laid me down on something hard, covered in a cloth so rough it felt like a potato sack. “I had to bring her somewhere. What did you want me to do, leave her? Anyway, the Maddox brothers are way too superstitious to go around making trouble. They probably think you’ll witch them or something. They won’t say anything.”

From across the room, Myloria spoke in a whisper. “Eric Fisher, I do not want this creature in my house.”

But her voice seemed to fall apart in the middle. She sounded so afraid that it made me frightened too, and I squeezed my hand tight around the little cloth bag.

Fisher stood over me, resting his hand on the top of my head. “I don’t think it’s got much to do with what you want,” he said, and the rough little tug when his fingers got caught in my hair was like the shiver when a cat licks your hand. I was just so grateful that someone in the world could stand to be near me. “I’m not concerned with what you all are doing out here—that’s your business—but I’m pretty sure she’s one of your people.”

The way he said the last part was as final as goodbye. Suddenly, all I knew was that I didn’t want him to go, and at the same time, I understood he was already walking out, and when he did, I’d be alone with a woman who could barely stand to be in the same room with me.

When he left, the house felt hollow, like the air after a thunderclap. We were alone—so alone that the whole kitchen seemed to echo.

Out in the yard, the car started up, roaring away in a storm of engine noise and gravel. Then, silence. In it, I was suddenly so afraid that I was still in the closet—that I had always been there and would never be anyplace else. I fumbled with my hands, reaching for the bricks, already half-convinced I felt the roots wrapped tight around my wrists. The stillness was so bottomless it made my chest hurt.

Then, Myloria moved closer. I could feel her standing over me, but couldn’t see her edges through my eyelids the way I had with Fisher. When I tried, all I got was a broken clatter, fuzzing at me like a TV, but I couldn’t tell if that meant something special about her or something special about him.

She made a low, unhappy sound—a breathing out. Then she bent over me and began to pick away the glass from around my eyes. Her hands were cool, and very careful, like she was worried I’d try to bite her. Next there was a cold pressure, followed by two hushed snips, soft as whispers. I tried to hold still, but her fingers were tickling my eyelids. They left a nagging itch, deep in my skin, and then I understood. She was pulling out the threads.

The first thing I saw when I opened my eyes was a burst of light so warm and red it could have been the sun or someone’s beating heart. I stared up at it, waiting for the room to come clear.

Then I blinked and the light above me was just a water-spotted lampshade made of red paper and dried flowers. In the middle, one flickering bulb swung gently on a plastic cord.

I was lying in a dim little kitchen. The curtains were pulled and only a sliver of light showed between them. At the sink, my aunt Myloria stood with her back to me.

Her hair was so dark it was almost black, arranged in a messy knot on top of her head. She had on a checkered halter top that tied at the neck and a pair of men’s undershorts with an ivy pattern. Her back was bare, so covered in tattoos that her whole skin seemed to be crawling with a tangle of blue-green snakes. Every inch of her was skinny, skinny, skinny.

I braced my hands on the table and sat up. “Myloria?”

She turned. Her collarbone showed and she had shoulders like a skeleton. Her face was beautiful, but in a sharp, unhealthy way, all jaw and cheekbones.

“How do you know my name?” she said, and now her voice was a long way from sweet. “What were you doing in my sister’s house?”

“Don’t you know who I am?” I whispered, gazing around at the peeling wallpaper and the chipped porcelain sink. The faucet was rusting, and underneath, there was a wet-looking rag tied around the bend in the pipe.

Myloria stared back at me—a blank, awful stare. I didn’t know what to do or say. I was dressed in a raggedy nightgown, sitting on a kitchen table, and my elegant, glamorous aunt now just looked used-up and hungry.

“I’m Clementine,” I whispered. “I’m your niece.”

She looked at me like I’d told her I was the president. “How dare you. How dare you come into my house and dishonor my sister. How dare you profane her memory.”

Her voice shook. I understood that people only talked about dishonoring someone’s memory when that person was dead.

The weight of it sat in my chest like a stone. I knew that it should hurt. And it did, but it wasn’t a breathless, skinned-raw hurt. It dug and bit at me. It ached.

I’d spent so many days—years—in a fog of sadness for my mother, knowing with a slow, ugly certainty that she was gone, but I hadn’t really known it in my heart until now.

Myloria stood with her arms around herself. In one hand, she still held a little pair of gold-colored sewing scissors.

“Don’t you remember me?” I whispered, and it sounded pitiful.

But she didn’t have to say a word. It was all there in her eyes. She didn’t.

“Please, you have to. I used to go around with Shiny all the time. I used to sleep over in the summer and make waffles and lemonade in your kitchen!”

“You’re a devil and a liar,” she said in a thin, shaking voice. “But you can’t work your tricks on me. My sister never had any children.”

I didn’t know how to argue. The fact that I was sitting there wasn’t a thing that needed to be argued. I was looking across the kitchen at my own aunt, and still, she was acting like I didn’t exist.

“Where’s Shiny?” I said. “Is Shiny here?”

Myloria only backed away, toward the other side of the room where an ancient round-cornered refrigerator hummed softly and a dark, narrow doorway led out of the kitchen.

I swung myself off the table, keeping my hands out to steady myself.

“Shiny!” I yelled. “Shiny, are you here?”

Myloria stood in the corner by the refrigerator, still clutching the scissors. “Stop! Stop it right now! Don’t you even talk to her!”

I was about to yell again when a voice answered from the dark little hall behind Myloria. “

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...