ONE

We push open the apartment building’s glass door, out into the yellow sunshine that’s a little too cheerful and bright. It’s hot as hell—the kind of heat that sticks to your skin, your hair, your freaking eyeballs.

“Christ, why did we sign up for this again?” Ezra says, his voice hoarse. “It’s so early. I could still be asleep.”

“I mean, eleven isn’t technically early. It’s—you know— about halfway through the day.”

Ezra lights a blunt he pulls out of I-don’t-know-where and offers it to me, and we suck on the last of it as we walk. Reggaeton blasts from a nearby park’s cookout. The smell of smoke and burning meat wafts over, along with the laughter and screams of kids. We cross the street, pausing when a man on a bike zooms by with a boom box blasting Biggie, and we

1

walk down the mold-slick stairs of the Bedford-Nostrand G stop, sliding our cards through the turnstile just as a train rumbles up to the platform.

The train doors slide shut behind us. It’s one of the older trains, with splotches of black gum plastered to the floor and messages written in Sharpie on the windows. R + J = 4EVA.

My first instinct is to roll my eyes, but if I’m honest with myself, I can feel jealousy sprouting in my chest. What does it feel like, to love someone so much that you’re willing to publicly bare your heart and soul with a black Sharpie? What is it like to even love someone at all? My name is Felix Love, but I’ve never actually been in love. I don’t know. The irony actually kind of **** with my head sometimes.

We grab a couple of orange seats. Ezra wipes a hand over his face as he yawns, leaning against my shoulder. It was my birthday last week, and we got into the habit of staying up until three in the morning and lying around all day. I’m seventeen now, and I can confirm that there isn’t much of a difference between sixteen and seventeen. Seventeen is just one of those in-between years, easily forgotten, like a Tuesday—stuck in between sweet sixteen and legal eighteen.

An older man dozes across from us. A woman stands with her baby stroller that’s filled with grocery bags. A hipster with a huge red beard holds his bicycle steady. The AC is blasting. Ezra sees me clutching myself against the ice-cold air, so he puts an arm over my shoulders. He’s my best friend—only friend, since I started at St. Catherine’s three years ago. We’re

2

not together like that, not in any way, shape, or form, but everyone else always gets the wrong idea. The older man sud- denly wakes up like he could smell the gay, and he doesn’t stop staring at us, even after I stare right back at him. The hipster gives us a reassuring smile. Two gay guys cuddling in the heart of Brooklyn shouldn’t feel this revolutionary, but suddenly, it does.

Maybe it’s the weed, or maybe it’s the fact that I’m that much closer to being an adult, but I suddenly feel a little reck- less. I whisper to Ez, “Wanna give this guy a show?”

I nod in the direction of the older man who has straight-up refused to look away. Ezra smirks and rubs his hand up and down my arm, and I snuggle closer to him, resting my head on his shoulder—and then Ez goes from zero to one hundred as he buries his face into my neck, which—okay—I’ve never actually gotten a whole lot of action before (i.e.: I’ve never even been kissed), and just feeling his mouth there kind of drives me crazy. I let out an embarrassing squeak-gasp, and Ezra puffs out a muffled laugh against the same **** spot.

I look up to see our audience staring, wide-eyed, totally scandalized. I wiggle my fingers at the man in a sarcastic half wave, but he must take that as an invitation to speak. “You know,” he goes, with a slight accent, “I have a grandson who’s gay.”

Ezra and I glance at each other with raised eyebrows. “Um. Okay,” I say.

The man nods. “Yes, yes—I never knew, and then one

3

day he sat me down, and my wife, Betsy, before she passed, and then he was crying, and he told us: I’m gay. He’d already known for years, but he didn’t say anything because he was so afraid of what we would think. I can’t blame him for being afraid. The stories you hear. And his own father . . . Heart- breaking. You’d think a parent would always love their child, no matter what.” He pauses in his monologue, looking around as the train begins to slow down. “Anyway. This is my stop.” He stands as the doors open. “You would like my grandson, I think. You two seem like very nice, gay boys.”

And with that, the man is lost to the platform as the woman with the baby stroller follows him out.

Ezra and I look at each other, and I burst out laughing. He shakes his head. “New York, man,” he says. “Seriously. Only in New York.”

We get off at Lorimer/Metropolitan and walk down and then back up a bunch of stairs to get to the L train. It’s June 1—the first day of Pride month in the city—so there are No Bigotry Allowed rainbow-colored signs plastered on the tiled walls. The platform is filled with pink-skinned Williamsburg hip- sters, and the train takes forever to come.

“Shit. We’re going to be late,” Ezra says. “Yeah. Well.”

“Declan’s going to be ****ed.”

I don’t really care, to be honest. Declan’s a ****. “Not like we can do anything about it, right?”

4

By the time the train arrives, everyone’s fighting to get on, and we’re all packed together, me crushed against Ezra, the smell of beer and BO slicking the air. The subway rattles and shakes, almost throwing us off our feet—until, finally, we make it to Union Square.

It’s a typical crowded afternoon in the city. The sheer amount of people—that’s what I hate most about Lower Manhattan. At least in Brooklyn, you can walk down the street without being bumped into by twenty different shoul- ders and handbags. At least in Brooklyn, you don’t have to worry if you’re literally invisible because of your brown skin. Sometimes I try to find a white person to walk behind, just so that when everyone jumps out of that person’s way, they won’t knock into me.

Ezra and I inch our way through the crowd and past the farmers’ market, the smell of fish following us. We’re dressed pretty much the way we always are: even though it’s summer, Ezra wears a black T-shirt, sleeves rolled up to his shoulders to show off his Klimt tattoo of Judith I and the Head of Holo fernes. He has on tight black jeans that’re cut off a few inches too high above his ankles, stained white Converses, and long socks with portraits of Andy Warhol. He has a gold septum piercing, and his thick, curly black hair is tied up in a bun, sides shaved.

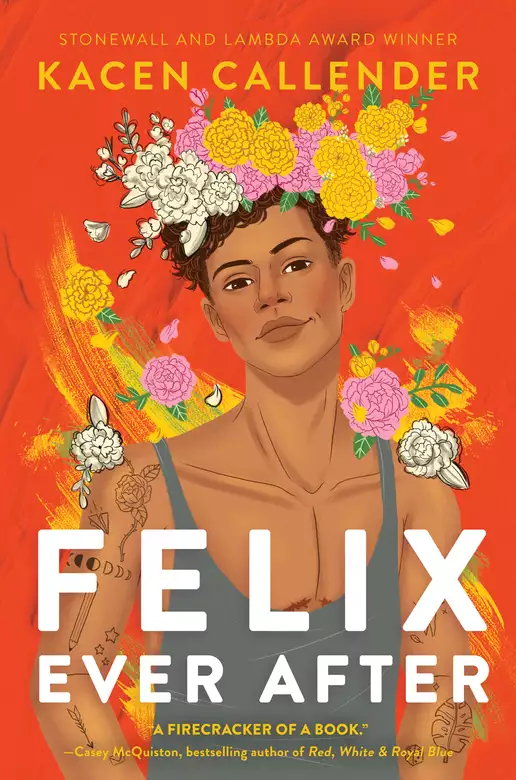

Whenever I’m around Ezra, eyes usually skip right over me to stare at him. I have curly hair, a loose gray tank that shows my dark scars on my chest, darker than the rest of my

5

golden-brown skin, a pair of denim shorts, smaller random tattoos that I’d gotten for twenty dollars down at Astor Place—my dad flipped out the first time, but he’s gotten used to them now—and worn-out sneakers that I’ve written and drawn all over with a Sharpie. Ezra thinks I’ve ruined them. He has a thing for keeping the purity of the designer’s intent.

We walk through the crowds of people who idle in front of the farmers’ market stalls selling jars of jam and freshly baked bread and flowers with bursts of color, men in business suits shoving past, dogs on leashes and toddlers on three- wheeled scooters threatening to trip us. We make it out of the farmers’ market and up the path that cuts through the green lawn where a few couples laid out on blankets. Some kids show off on their skateboards. Girls in summer dresses and shades lounge on benches with books that they aren’t really reading.

“Why’d we decide to do this summer program again?” Ezra says.

“For our college applications.”

“I already told you. I’m not going to college.”

“Oh. Then, yeah, I have no idea why you’re doing this.”

He smirks at me. We both know he’s probably just going to live off his trust fund when he graduates. Ezra is part Black, part Bengali, and his parents are filthy rich. So rich that they bought Ezra an apartment just so that he can live in Bed- Stuy for the summer while he’s in the arts program. (And these days, apartments like Ezra’s are just about a million

6

dollars.) The Patels are the stereotypical Manhattan elite: endless champagne, fund-raisers, gala balls, and zero time for their own son, who was raised by three different nannies. It’s ****ed-up, but I have to admit that I’m jealous. Ezra’s got his entire life laid out for him on a golden platter, while I’m going to have to claw and scrape and battle for what I want.

My dream has always been to go to Brown University, but my grades aren’t exactly stellar, my test scores are less than average, and their acceptance rate is 9 percent. It isn’t that I haven’t tried. I studied my *** off for the tests, and I write down every word my teachers say in class to stop my mind from wandering. Like my dad’s said, my brain is just wired differently.

The fact that I almost certainly won’t get into Brown sometimes makes me feel like there’s no point in even trying. But people have gotten in despite s****y test scores before, and even if my grades suck, my art doesn’t. I’m talented. I know that I am. The portfolio counts even more for students applying to focus on art, and since the St. Catherine’s sum- mer program offers extra credit, there’s a chance I could raise my grades up from Cs and Bs. I might still have a shot of getting in.

Leah, Marisol, and Declan are already on the Union Square steps for the fashion shoot. St. Cat’s is on a different schedule from most NYC schools, and the summer program officially began a few days ago. St. Catherine’s likes to kick off the summer program with projects so that we can get to

7

know the students from other classes. Ezra and I signed up for a fashion shoot, using some of his designs. Leah, with her bushy red hair and super-pale skin and curves and tank top and slightly revealing booty shorts, has her camera, ready to take photos. And, of course, Marisol is the model. She’s just as tall as Ezra, olive skin and thick brown hair and Cara Delevingne eyebrows. Just seeing her makes my nerves pump through my chest. Her hair’s a giant nest, and she has green feathers glued to her eyelashes to match her lipstick. She wears the fourth dress in the lineup we’d planned: a sequin-portrait of Rihanna.

Declan Keane is running this whole thing as the director, which really just annoys the crap out of me. He doesn’t have any experience as a director whatsoever, but somehow, he always manages to weasel his way into everything. It doesn’t help that Declan acts like it’s his only mission in life to treat me and Ezra like shit. He talks crap about us every chance that he gets. He hates us, and he’s on a crusade to make every- one else hate us, too.

Declan’s busy talking to Marisol when he sees us coming.

His eyes flash. He clenches his jaw.

“So nice to see you,” he calls out to us as we walk over, loud enough that a few people lounging on the steps turn their heads. “Ezra, thanks so much for coming.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved