- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

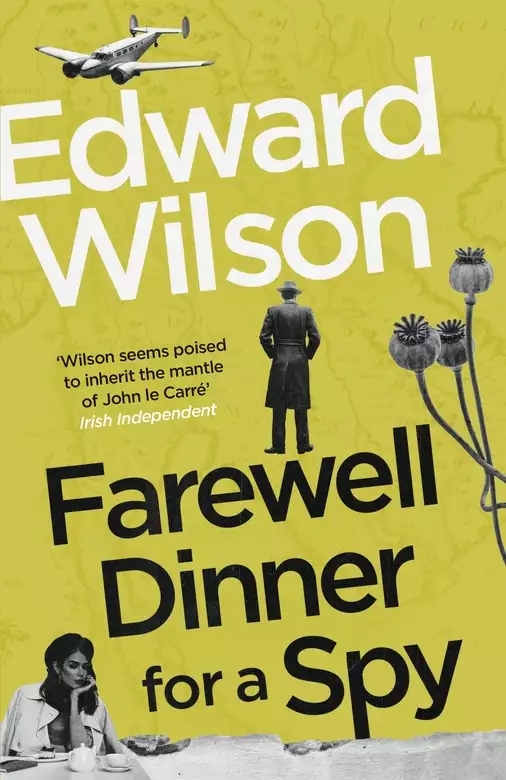

"A compelling slice of mid-century espionage that expertly blends history with possibility. All comparisons that will inevitably be made with le Carré are entirely apt" Tim Glister

'Edward Wilson seems poised to inherit the mantle of John le Carré' Irish Independent

1949: William Catesby returns to London in disgrace, accused of murdering a 'double-dipper' the Americans believed to be one of their own. His left-wing sympathies have him singled out as a traitor.

Henry Bone throws him a lifeline, sending him to Marseille, ostensibly to report on dockers' strikes and keep tabs on the errant wife of a British diplomat. But there's a catch. For his cover story, he's demobbed from the service and tricked out as a writer researching a book on the Resistance.

In Marseille, Catesby is caught in a deadly vice between the CIA and the mafia, who are colluding to fuel the war in Indochina. Swept eastwards to Laos himself, he remains uncertain of the true purpose behind his mission, though he has his suspicions: Bone has murder on his mind, and the target is a former comrade from Catesby's SOE days. The question is, which one.

Release date: January 18, 2024

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Farewell Dinner for a Spy

Edward Wilson

Julot’s restaurant was packed with more than a hundred guests. They spilled out onto a candlelit terrace, where the lesser mobsters were seated. The meal kicked off with the traditional Marseille amuse-bouche, a tapenade of marinated olives served on tiny rounds of toast. The simplest of nibbles, intended to stimulate the appetite for the more complex creations that were to follow. The amuse-bouche plates had just been cleared away when the unfortunate news began to percolate. The guest of honour wasn’t going to be there. Everyone wanted to know what had happened. The rumours filtered out from those seated nearest the boss. Lester, the much-loved American, had suddenly been summoned back to Washington as a matter of extreme urgency. This confirmed the impression that Lester, despite his easy-going ways and love of partying, was indeed a très, très important Américain. One strand of conjecture was that it had something to do with events in Korea: the president was planning a move and needed Lester’s advice. ‘He is, as we know,’ whispered another gangster, ‘Washington’s number one man on Asia.’ ‘Which is,’ laughed another voyou, ‘why he was so useful to us in Indochine.’ Another put his hand up, ‘Shhh!’

The boss stood up and motioned for silence. ‘I have just received a message from Lester.’ He smiled. ‘I will not try to imitate his inimitable accent, but, oddly, his written French is better than his spoken.’ He smiled again, put on his reading glasses, and began. ‘“To my dear friends. The pilot has assured me that the control tower will copy this message and deliver it to a waiting car. The driver, who once won the Tour de Corse, should arrive at Julot’s well before the bouillabaisse. Your wonderful sea, by the way, is beautiful from up here. The sky is a perfect cloudless blue and the air hostess has just brought me another glass of champagne which I now raise in a toast to all of you.”’ The boss gestured and everyone stood up. He then continued reading. ‘“To all my friends in Marseille, the best friends in the world!”’ Everyone raised their glasses and drank. The boss put down his champagne flute and folded his reading glasses into a case. There was concern on his face.

It was now time for the bouillabaisse, a speciality of the house. Julot’s recipe was so highly esteemed that a world-renowned film director and author sometimes came to partake. Julot claimed that his restaurant and bouillabaisse had inspired one of the man’s films – a claim that, however merited, was never verified. As the legendary fish soup made its entrée, borne in a huge steaming tub by two brawny waiters, a few of the guests called out, bullabessa, the name of the dish in Provençal Occitan. A true bullabessa contained at least five different types of fish and shellfish. The most essential ingredients were rascasse – a lethal red fish with poisonous spines – olive oil and the best saffron you could find. If available, monkfish, conger eel or even an octopus could be added. But shellfish were more important for the flavour. Sea urchins, small spiny creatures that cling to rocks or wrecks, were abundant in the seas around Marseille and easy to gather. Spider crabs were a delicious luxury that everyone hoped to find in their portion of bouillabaisse, but you savoured the broth and rouille first before tucking into the crab meat and fish. The waiters had already finished laying soup plates and other waiters were now ladling the soup from steaming metal bowls and placing out smaller bowls containing the rouille, a sauce concocted of olive oil, egg yolks, saffron and garlic. You consumed the soup with pieces of grilled bread on which you spread your rouille.

William Catesby and Kit Fournier were the only guests who didn’t come from Marseille, Corsica or Italy. Fournier was on the opposite side of the table from Catesby, but not directly. The guest facing Catesby was a Corsican with a scarred face and one and a half fingers missing from his right hand. They had chatted briefly about wine – the Corsican had already instructed the wine waiter to find a couple of bottles of white wine from a small Cassis château for their table. ‘It is,’ he said, ‘an Ugni blanc, one of the few wines that pair well with bouillabaisse. Let me know what you think.’

‘Thank you,’ said Catesby, but he was hardly going to disagree with a gangster who knew the turf. Catesby spread a dab of rouille on a round of toast and inhaled the wonderfully fragrant broth. He fully appreciated that it had been cooked with infinite care. He sipped a spoonful. It was delicious beyond measure – a world away from austerity Britain, where some foods were still rationed. Catesby popped the toast into his mouth and washed it down with a gulp of Cassis Ugni blanc. He smiled at the Corsican. ‘You chose well, monsieur, it is perfect. Full bodied with a herbal aroma.’

Catesby looked over to Kit Fournier who was wolfing down the soup. ‘Take your time, Kit, there’s a lot more to come.’

‘I’m looking forward to the crabs. I grew up with them.’

Catesby decided not to make a lame joke.

‘We used to catch Chesapeake blue crabs in the river and when we had a dozen or so my mother would steam them with Old Bay seasoning. They made a helluva racket in the big pot trying to escape.’

Catesby nodded. The gangsters of Marseille were capable of great cruelty, but their cooks didn’t boil their crabs and lobsters alive. But how, thought Catesby, do they kill them? The techniques necessary were not taught on the Secret Intelligence Service’s induction course. The best kills, of course, were those that could pass as death by suicide or natural causes – but who was going to get a crab drunk and push him over the railing of a tenth-floor balcony? Drugs, thought Catesby. Drugs were ugly, but quiet and effective. The Russians loved them, but the toffs running the British Secret Intelligence Service were squeamish about poison.

The waiters were now passing around trays of crusty bread to soak up the bouillabaisse. The staff were all men in smart serving gear. There was not a woman to be seen among either the guests or the servers. As far as the mafia were concerned, women were stay-at-home wives, child bearers or prostitutes. The older ones, however, could be elevated to the status of background advisers.

‘I love crab too,’ said Catesby looking at Kit, ‘but I’m also looking forward to a big slice or two of monkfish – and maybe some conger eel. I remember one bouillabaisse that contained the head of a conger – an enormous beast.’

Julot was now standing centre stage like a magician behind the huge steaming tub of bouillabaisse. The treasures of the depths were about to appear. The first morsels to emerge steaming and dripping from his tongs were whole rascasse and spider crabs; the next were chunky fillets of monkfish that were still whole after the long cook. Julot smiled as he piled high the serving tray. He dipped his exploratory tongs deep into the tub – and then started probing. A look of consternation crossed his face. He looked at the diners and laughed. ‘I don’t know what my sous chefs have been up to.’ He turned towards the kitchen and shouted, ‘Hey, Fabio, what have you put in the bouillabaisse? A shark’s head?’

A voice replied, ‘Only the usual, Julot.’

‘I don’t think so, Fabio. Come and help me lift this monster out.’

Fabio came out of the kitchen in a chef’s toque and neckerchief. He wiped his hands on a napkin and stared at the tub of bouillabaisse. Julot handed him a pair of tongs. The chef prodded into the steaming cauldron.

‘It’s pretty solid,’ said Julot. ‘Try to find a hole to get a grip.’

A human head slowly arose out of the bouillabaisse. The victim’s hair was stained orange from the bouillabaisse broth and his mouth was hanging open, more in surprise than agony.

Meanwhile, Kit Fournier had begun to retch. Catesby passed over his napkin and said, ‘Let me help you.’

‘No,’ said Kit, ‘I’m okay.’ He stifled another vomit and headed towards the lavatories.

As Catesby watched Fournier disappear, he thought: CIA agents should be made of sterner stuff. He shrugged and mechanically poured himself another glass of Ugni blanc. Kit’s vomiting had made him want to wash away the taste of the bouillabaisse. Catesby was a little ashamed that, rather than feeling shock and repugnance, he had already begun to analyse the situation. He was cold-blooded and would have made a good cop. And his first question would have been: Whose head is it? The second: Who killed him? And one more: Why? He then strained to hear a whispered conversation between the Corsican mobster sitting opposite him and another who had joined him. They were speaking Corsu, a language that Catesby struggled to comprehend. The only words he picked up were: Hè Roberto, un venditore di Napuli – which he construed as ‘It was Roberto, a dealer from Naples’. The other Corsican shook his head rapidly and said, Innò, nò, nò. Roberto hè sempre vivu è vàcù u capu – which led Catesby to assume that Roberto was still alive and on fine terms with the capu, the boss. The rest of the conversation was incomprehensible to Catesby. There was a lot of shouting in the restaurant and the tub of bouillabaisse had been removed with some haste. A waiter had joined the two Corsicans and as he shepherded them out of the restaurant, he said something that made them laugh. The waiter then looked at Catesby and addressed him in standard French, ‘No problem, monsieur, the head belongs to a drowned sailor. Another restaurant owner put it there because he wants to destroy Julot’s reputation as serving the best bouillabaisse in Marseille.’

‘Whoever put that head in the cooking pot certainly ruined a marvellous bouillabaisse,’ said Catesby in amical agreement.

The waiter bowed as he backed away. ‘I am sorry, monsieur, if this unfortunate event has ruined your evening.’

The drowned sailor tale, thought Catesby, was exactly the sort of explanation that the local police would accept with gratitude. Case solved. The alternative, investigating the mafia, was both difficult and dangerous. Marseille was a town where the parade of killers, victims and motives was long and complicated. If Catesby was a local cop, the first person he would call in for questioning would be Lester Roach. He reckoned there were two likely reasons why Lester hadn’t turned up for his farewell dinner. One, he was the killer. Two, he knew there was at least one person at the dinner who was aiming to kill him.

Kit Fournier had reappeared from the lavs. He had scrubbed away every trace of bouillabaisse from his lips, but his face still looked stunned. Catesby took the American firmly by the elbow. ‘We’ve got to get out of here.’

‘Good, I need some fresh air.’

They began walking in the direction of Le Vieux Port. There were a lot of questions that Catesby wanted to ask Kit Fournier – not as a cop, but as a member of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. London needed to know the latest.

It was only very late in life that Catesby began to tell the whole story, not just the highly classified intrigues of the secret state – but secrets of the inner mind. Members of the Secret Intelligence Service were not just spies, they were also human beings – although some of them didn’t realise it. Maybe it was because they had never found someone they could talk to; someone who really wanted to listen and understand. Catesby was lucky. He had Leanna, his granddaughter. Part of the reason that Catesby had taken early retirement was to help look after Leanna after her mother had died in mysterious circumstances in Africa. As a teenager, she had found her grandfather non-judgemental and totally impossible to shock – and even a little outrageous in his own right. Consequently, she told him everything, no matter how shameful. Later, Leanna became a professor of modern history at a London university. Now, it was Catesby’s turn to tell her everything, no matter how shameful.

It was a clear cold winter’s day, and they were sitting on a bench overlooking the sea at Dunwich. Catesby had made a flask of hot rum toddy and passed a tumbler to Leanna.

‘This is delicious, Granddad – and a perfect treat for a day like today.’

‘I got the idea from Henry Bone, but I’m sure it doesn’t follow his recipe entirely. Henry put a lot more rum in his, and the wine was a good-quality Burgundy.’

‘I bet you were sitting on a bench in Green Park passing on information that was too sensitive to be discussed in the office.’

‘No, we were sitting on a bench in Dorotheenstadt Cemetery in East Berlin, next to the grave of a resistance fighter executed by the Nazis. We were waiting for a contact who never turned up, so we finished the rum toddy – which we needed because it was a very cold day.’

Leanna stared hard at the winter sea. ‘Did ideology ever get in your way, Granddad?’

‘It did, but I hope I never let it blind me – as it did some others.’

‘You knew them all, didn’t you?’

Catesby laughed. ‘Who do you mean by “all”?’

‘Let’s start with Philby, Maclean and Burgess.’

‘Yes, I knew them, but not terribly well – but then again who did? In fact, at first, I thought that Philby and Burgess were Tory right-wingers who had signed up for America’s anti-communist witch hunt. Your grandmother, who had just started working at Five, had a much better idea of who they really were.’

‘Granny says that Philby and Burgess were the reason you ended up in Marseille.’

‘Part of the reason. I’m sure there were other factors. Maybe they chose me because I was a young and junior officer who was expendable – a cheap pawn sacrifice to buy off the Americans.’

‘Could your fluent French have been a reason?’

‘If language skills were a factor, they should have sent someone who spoke Corsican, Italian and the local patois as well. No, Leanna, I was a useful stooge, someone easily manipulated to do the bidding of my betters.’

‘I think, Granddad, you are too harsh on yourself.’

‘Hmm, how kind of you to say so. Well, to be less harsh on myself, I joined the Secret Intelligence Service because I needed a job. I had just married your grandmother and acquired two stepchildren who were toddlers. I was also flattered that someone like me, a rough kid from the Lowestoft docks, had been invited to join an elite secret club. But the Marseille business cleared away any illusions I had of ever becoming one of them. Sure, I got pretty good at affecting their voices and manners.’ Catesby smiled. ‘We ought to send spies to drama school. Even Michael Caine learned how to play a credible toff. Marseille taught me that the intelligence service regarded me as a disposable tool for doing their dirty work.’

‘But you eventually rose to a very high post.’

Catesby shrugged. ‘Low cunning – and I learned to play their game.’

‘What are the rules of their game?’

‘There are no rules – that is the very essence of the game. The most important thing about the Marseille op, and many others, was deniability – not the faintest fingerprint leading back to Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service.’

‘And you still haven’t said how you, then a German desk specialist, ended up in Marseille.’

‘I still don’t know.’

‘Granny says that you were falsely framed as a Soviet double agent by actual doubles who were trying to save their own skins.’

‘An interesting theory.’

When you fish a body out of a canal the presence of Jesus should be welcomed with solemn piety. But not when it’s James Jesus Angleton, a rising CIA star making a name for himself in Europe. Angleton’s devout Catholic Mexican mother had insisted upon his middle name – and, like his holy namesake, Angleton seemed to turn up everywhere.

The divided city was a playground for spies, but a dangerous playground where kids shove other kids off climbing frames and hide sharp spikes at the bottom of a fast slide. And don’t trust the kind-looking old granny who offers to push your swing. She keeps a stiletto and poisoned sweets in her handbag.

Catesby was first assigned to the city at the beginning of the Berlin Blockade, when the Soviet Union cut off all land access to the city and tried to starve the allies out of West Berlin. The only option was a massive airlift of 2,000 tons of supplies per day to sustain the allied troops and the two million civilians in the western sectors. There were casualties. On one occasion, Catesby had to make a risky trip into the Soviet sector to collect the bodies of a British aircrew after their Vickers Viking collided with the Soviet fighter that had been buzzing it. Collecting the body parts was gruesome – and the stern faces of the heavily armed Soviet soldiers watching Catesby and his team didn’t make it any easier. Being marched off into internment for crossing into East Germany was a real possibility. But it didn’t happen, and Catesby began to develop a reputation as someone who could do the dirty work.

Even when the blockade ended in June 1949, Berlin remained a city under siege. It was, more than ever, an espionage swamp full of double-dipper spivs wanting to make a fast buck. Double dippers were greedy agents who sold intelligence to both sides. It was a dangerous occupation – as one of Catesby’s double dippers found out.

The branch of the Landwehr Canal where the corpse had been found was firmly in the British sector – and had been cordoned off by Royal Military Police. The dead man’s face was glistening in the summer sunshine as Catesby leaned over to confirm his identity.

‘Dieter was one of yours,’ said Angleton. He sounded sober but his voice was raspy.

‘Yes, he was.’

‘He was one of ours too.’

‘We’ll have to arrange a post-mortem,’ said Catesby.

‘And where will this autopsy take place?’

‘I assume at the BMH.’

‘The British Military Hospital?’

Catesby nodded.

‘We’ll send observers and one of our own pathologists.’

‘And flowers too, if you like.’ Catesby looked at Angleton and was pleased to see that he was getting on his nerves. Meanwhile, two RAMC corpsmen were making their way up the canal path carrying a stretcher. ‘I think,’ said Catesby glancing at the body, ‘it’s time to say goodbye.’

The post-mortem ended up being quite a big deal. London sent over a leading forensic pathologist and the Americans matched him with one of their own who was a prof at the Sorbonne. Catesby didn’t understand why they were making such a fuss over the death of a very minor player. No one even knew Dieter’s real name. They usually called him Herr Schwindler, Mr Cheat. In the end, both pathologists ruled out drowning or suicide. The cause of Dieter’s death was a massive heart attack, but not one caused by coronary problems. Traces of cyanide were found in his nasal passages. It was agreed that Dieter had been sprayed with a jet of cyanide gas. The double-barrelled cyanide spray gun was a weapon the Russians had used before to deal with double agents and dissidents. By taking out Dieter, Spiridon – the Sov spy who ran their ops in Berlin – had got rid of one double dipper and sent out a warning message to others. As far as Catesby was concerned the matter was done and dusted and he got back to his usual routine of gathering intelligence in the spy capital of the world. When the urgent summons to London arrived, he was stumped at first – but then remembered Angleton’s face staring at him over Dieter’s dead body. Bastard.

The security officer at the entrance desk was a retired Black Watch NCO wearing his regimental kilt. He gave Catesby’s ID a cursory look and passed over the signing-in log. The security officer then picked up an internal telephone and spoke in hushed tones. He looked up and said, ‘Mr Ramsay will see you now, Captain Catesby.’

Neil Ramsay was head of personnel. In a time of post-war austerity, the department had become known as A&E, Accident and Emergency. When an officer was summoned to A&E, it meant that the next stop would be the mortuary, intensive care, rehab or – for the lucky ones – return to normal duties.

Ramsay was sitting at a desk laden with mountains of beige and grey files. Like the security officer on the entrance door, the head of personnel was a Scot. He had a pleasant welcoming manner but spoke with an accent that was both refined and unintelligible. Catesby thought the number of Scots in the SIS was out of proportion to their actual number in the UK population. Were they positioning for a Celtic coup d’état?

Ramsay’s reading glasses were at an odd angle. It looked like the frames had been badly bent, as if someone had sat on them. Only one lens was in position, and it magnified his eyeball into a huge menacing glare. He looked like a Cyclops, but the Scotsman’s voice was that of a bored bureaucrat. ‘We must inform you that your personnel records have been requested by another member of SIS and passed on to that person. As is always the case, it required the agreement of the Director. It is now procedure to inform all officers when this happens. Unless, of course, it is a matter of gross misconduct or national security.’

‘So I haven’t been accused of murder?’ Catesby immediately regretted saying his thoughts out loud. Bloody Dieter again.

‘Oh, nothing as minor as a murder or two. I am sure Mr Philby wouldn’t have been interested in your records if the only thing you did was go around killing people.’

‘I haven’t killed anyone.’

‘I was, Mr Catesby, only teasing. Sassenachs don’t always get our sense of humour.’

‘Sorry.’ Catesby forced a smile. ‘A Glaswegian walks into a café and asks the waiter, “Is that a cake or a meringue?”’

‘And the waiter replies, “You’re not wrong, it is a cake.” Very good, but you need to work on the accent before you tell that one again.’

‘Can you give me lessons?’

‘Ach no, I don’t want to be accused of preparing you to defect to Scotland.’

‘On a lighter note, have I been recalled to London just to be told that my personnel file has been passed on?’

‘I would guess that there’s more to it than that, but I haven’t been informed. Everything is “need-to-know” nowadays.’ Ramsay looked at a memo on his desk. ‘You have pending appointments with both the Director and Commander Bone, but your first meeting will be this morning at the Foreign Office with Mr Philby and Mr Burgess.’

‘I thought that Kim Philby was head of intelligence in Istanbul. What’s he doing in London?’

Ramsay closed his eyes and looked pained. ‘We never say “head of intelligence”. Mr Philby’s job in Turkey was “First Secretary at the British Consulate”, but he is now in London pending reassignment. I’d now like to have a look at your expenses and leave arrangements. Why are you yawning?’

‘Because I’m ill-mannered.’

‘Try not to be when you see the Director.’ Ramsay looked at his watch. ‘Philby and Burgess are expecting you at eleven. If we finish up quickly, you’ll have plenty of time to saunter over to the Foreign Office.’

‘Has Burgess had a peek at my records too?’

‘His name isn’t on the access list.’

Catesby frowned. Burgess was a loudmouthed drunk and the last person he wanted perusing his personnel file.

The walk to the Foreign Office from Broadway Buildings, the ugly 1920s office block that housed SIS, took eight minutes if you stepped out briskly and didn’t take the picturesque detour through St James’s Park. As Catesby turned through the archway into King Charles Street he was oddly pleased by the air of shabbiness. In the era of post-war austerity, the once imperial grandeur of Whitehall was now faded and soot-stained. When Catesby entered the foyer of the FO, he was surprised there was no cop to check his ID. Standards, eh? He could have been any old Russian agent. Because Philby no longer had his own office in Whitehall, Guy Burgess’s had been chosen as a meeting place. Catesby had to ask three times before he found someone who could direct him to Burgess’s office. His jobs seemed to keep changing – and he had now landed on the China desk. Why the fuck, thought Catesby, would a China desk man want to see him? He shook his head and knocked on the door.

A loud voice bellowed, ‘Come in, come in . . .’ At first glance, Guy Burgess seemed the essence of casual chic and bonhomie – but the favourable impression didn’t last long. Burgess’s Eton tie was stained with food and drink – and its wearer seemed somewhere between half blotto and totally blotto even though it was only eleven in the morning. He poured Catesby a stiff whisky without asking if Catesby wanted one.

‘Thank you for coming at such short notice.’ Burgess eyed up Catesby as if he were a menu item, but then looked away. ‘You’re a welcome relief from China. Mao’s won, but the Yanks don’t want to admit it.’ Burgess sipped his drink. ‘Our current dilemma is granting Mao UK diplomatic recognition. As you know, we always recognise the government in control – even if it’s led by Satan and his minions. But the Americans are different, particularly in the case of Mao.’ Burgess was suddenly unsteady on his feet and spilled his drink. ‘I think I’d better sit down. Had a bit of a tumble a few months ago; bad head injury – spent a few weeks in hospital.’

Catesby never found out the full truth of what had happened, but it apparently involved falling down the stairs at a Pall Mall club.

‘We must humour the Yanks – and do what we can to make sure that other bits of Asia don’t tip over into the communist camp. That’s why we’re beefing up our forces in Malaya. But the most important piece to save is French Indochina – and the dock strikes in Marseille aren’t helping. The communist-controlled unions are preventing ships from being loaded with troops and supplies for Indochina.’ Burgess closed his eyes as if he had decided to have a brief nap. Catesby wondered if he should shake him awake before he tumbled out of his chair. It might not be a good idea to aggravate that head injury. Another minute passed before Burgess yawned and opened his eyes. He was now staring at an open folder on his desk. ‘I see you were at King’s and studied under the charming Basil – and, very impressive, you were one of the daring night climbers.’

Catesby faked a smile but was furious that Philby had let someone else see his file. He was also surprised that his file was so thorough. He had never told anyone in SIS that he had been a member of the night climbers, a clandestine group of undergraduates who defied the authorities by scaling the university’s numerous spires and then leaving a souvenir, such as a scarf or a hat, to show what they had done.

‘Who did you climb with?’

Catesby gave three names, none of whom could be summoned by Burgess for interrogation. Two had been killed in the war and the third had emigrated to New Zealand.

‘We all admired you climbers – such daring defiance.’

Despite the flattery, Catesby felt uncomfortable. He stared at his glass and realised it was a priceless Dartington crystal tumbler. His wife had inherited a set of six and they were only to be used on special occasions. Catesby sipped the whisky, and it was pretty fine too. Maybe being a drunken toff wasn’t such a bad way of life.

‘Top up?’ said Burgess.

Catesby nodded.

‘Ah, I think Kim’s here.’

There wasn’t a knock, the door just opened and Philby walked in. ‘Greetings, Kim,’ said Burgess. ‘Can I get you a drink?’

‘Don’t get up. I’ll help myself.’ Philby went over to a side cabinet which contained a small fridge. ‘There doesn’t seem to be any gin – or ice cubes or tonic either.’

‘I’ve had a few visits from Anthony.’

‘Well, it looks like whisky then.’ As Philby poured himself a generous slug, he glanced at Catesby. ‘I think we’ve met before.’

‘Yes, it was just before my first deployment to France with SOE.’

‘It m-m-must have been at St Ermin’s Hotel w-when I was head of D Section.’

‘Yes, it was.’

‘I’ve asked you here,’ said Philby, ‘to talk about your time in Occupied France.’ The stutter was gone. He went over to Burgess’s desk and picked up a thick file that was Catesby’s life story. Philby began to skim through the paperwork and from time to time he nodded and cleared his throat.

Catesby wanted to grab the file from Philby’s hands and shout, What the fuck are you looking at!

Philby finally put down the file and stared at Catesby. ‘The Resistance group that you worked with was led by communists, several of whom are now leading the strikes in Marseille. Does the name Gaston le Mat ring a bell?’

‘The other Maquisards called him that. It means Gaston the Mad in the local dialect. I don’t know his real name.’

‘Well, Gaston – mad or sane – is now a high-level union organiser and an influential member of the Communist Party.’

Catesby tried not to shout. ‘What’s that have to d

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...