- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

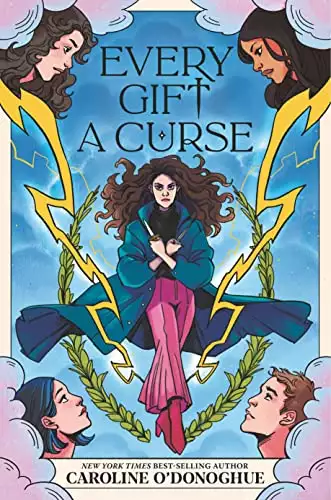

Magic-sensitive Maeve wants to save the innocent from a dangerous cult. But how much can she delve into darkness without becoming what she fears? The exciting conclusion to the Gifts series.

Big things are happening for Maeve and her tight-knit coven in Kilbeg, Ireland. Fiona lands a role on a TV show, Roe’s band is poised to hit the big leagues, and Lily is embracing a new style and outlook. Then there’s Maeve, whose magic is growing stronger all the time. Yet she finds herself increasingly lashing out, doing and saying cruel things without knowing why. When her recurring dreams begin to involve her physically manifesting in other places, including enemy-turned-maybe-friend Aaron’s bedroom, Maeve realizes the power she wields might not be entirely under her control. She tries to keep her struggle a secret, even if it means pushing her friends away. But when she learns the religious cult the Children of Brigid is kidnapping and torturing vulnerable teenagers, Maeve realizes the only way to free their prisoners is to risk letting an older magic consume her. This enthralling story of friendship and identity is also a story of being at a crossroads between youth and adulthood and picking your path forward.

Release date: May 9, 2023

Publisher: Walker Books US

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Every Gift a Curse

Caroline O’Donoghue

Chapter 1

being cursed: The first thing you feel is fear. But the second thing—the thing you really notice—is beauty. The world is so beautiful when you don’t think you’ll have long to look at it.

The colors shine brighter. Even now, in the December twilight, when it’s almost completely dark. The chilly mist from the river melds with the light of the city, and all you can see is a gold-and-blue blur. A box of jewels you need to squint your eyes just to look at. The sense of a city dancing in your blood.

Thirty-six days have passed since I became responsible for the deaths of two women. One who tried to kill me; the other who died trying to save my life.

“There you are,” Fiona says, flinging open the door to Nuala’s house. No matter how early I get to Nuala’s house these days, she’s always here first. “Come on, the Apocalypse Society is already in session.”

She takes me through to the kitchen, and everyone’s here: Manon, studying a bound stack of paper; Nuala, taking something out of the oven; Roe, peeling an apple with a knife; Lily, sitting on the kitchen counter.

The question: Were we directly responsible for the death of Heather Banbury and Sister Assumpta, or was it all an accident? Does the Housekeeper even care about accidents, or does she swing the ax regardless of who’s guilty?

“That’s the problem,” Nuala says midflow, gesturing with a wooden spoon. “The Housekeeper is revenge without judgment. She’s not a thing who can make her mind up. She’s a windup toy. Isn’t that right, Maeve?”

I haven’t even taken my coat off. “How come no one ever says hello to me anymore?” I say indignantly. “What am I? Dead?”

“Not yet,” Manon muses, highlighting a line of text with a yellow marker. “But soon, perhaps.”

“Well, joyeux Noël to you too.”

We know of three Housekeeper summonings, spread out over the last thirty years. The first

was when she was summoned by Nuala’s sister, Heaven, who traded her own life to bring on the death of their abusive father.

The second was Aaron, when he called her to break out of his far-right Christian rehab center. She took his friend then. Matthew Madison. A death that Aaron spent three misguided years trying to atone for within the gnarled fingers of the Children of Brigid.

And the third: Lily. A botched tarot reading that ended in chaos, and that brought us all together.

Who knows what a fourth visit might bring about? Who might fall victim, and who might be spared? Aaron hasn’t waited around to find out.

I bend down to kiss Roe on the cheek, the movement unraveling my thick scarf.

“Hello,” he says, nuzzling me. “You’re cold.”

“Hey.” Lily is drawing on the window with acrylic craft paint, her knees under the sill, feet trailing in the kitchen sink. She appears to be drawing a very complicated pig, its face filled with red and green swirls.

“What’s this?”

“A boar. A yule boar.”

“Of course.”

Lily pushes a strand of blond hair back off her face. “I didn’t want to do something boring like a Christmas tree. I thought we would do something pagan. For winter solstice.”

“Hence the yule boar.”

Lily starts to smile to herself and keeps painting. “Hence the yule boar, yes.”

When Lily and I summoned the Housekeeper, it happened in days. And we hadn’t even meant to call her. She was just a spirit who was accidentally woken by a combination of my sensitivity, the Well of magic below Kilbeg, and the throbbing hatred Lily and I had for each other. Dorey told me almost a month ago that she was planning on calling the Housekeeper—surely she would have done it by now.

Dorey’s warning to me was clear. She spoke like the Queen of the Fairies, offering foul

bargains through a glinting smile. The Children wanted total dominion over the Well in Kilbeg, and would do anything to get it. Anything, that is, except kill us. Murder in the magical world is more trouble than it’s worth: everything comes back to you eventually. But if you have just cause for summoning something like the Housekeeper, you can let her do the dirty work for you.

So where is she?

“We must first understand,” Manon says, “whether they truly do have just cause.”

“We killed Heather Banbury,” Roe says flatly.

“No, we didn’t,” Fiona responds, her voice unusually high-pitched. “She accidentally died.”

“While she was magically bound to our will,” Nuala corrects. “Although, if the Children hadn’t come to the tennis courts, it wouldn’t have happened at all. So they could be equally responsible.”

“In the eyes of who?” Lily asks, still painting her boar.

“I don’t know.” Nuala throws her hands up. “The great cosmic abacus that doles out fairness?”

“Justice,” Fiona says, holding up the tarot card. I might be the sensitive, but Fiona’s eye for tarot is now every bit as good as mine. She shuffles the pack and straightens the cards, tapping the deck twice on the table so they’re neatly aligned.

At that moment, as if in response, there is a tap on the glass panel of the kitchen door. An orange-tipped magpie flutters outside, waiting to be let in. Fiona reaches for the handle.

“We cannot let that thing in here,” says Manon, wrinkling her nose.

“Don’t talk about Paolo that way,” Fiona says defensively. Paolo and Manon have very quickly become the two great obsessions of Fiona’s life, and so of course they are permanently in opposition.

Manon shudders. “I hate birds.”

Paolo the magpie hops in and balances himself on the long arm of the tap. Lily shuffles her feet over. Paolo starts noodling the spout with his beak, looking for

drops of water.

“Can I fill a bowl, Nuala?” Fi asks.

“You can, love.”

“Fionnuala!” Manon protests. Manon has an abandoned child’s tendency to be overly formal with her own mother. “Fin.”

“Manny,” Nuala replies soothingly. “He’s no harm.”

“I don’t like him.”

I’m nearest the cupboard, so I fill a bowl for Paolo. I even get him the filtered water, out of the fridge. I don’t have any sense of what Paolo thinks or feels, but I do think that he prefers filtered water. He’s Fiona’s familiar, after all, and Fiona does enjoy the finer things.

Fiona rests her gaze on him and, after a moment, he comes to perch on her shoulder.

“Well?” I ask, trying not to sound too expectant. “Does he have any news?”

Fi tilts her head for a moment, then closes her eyes. The magpie doesn’t touch her, doesn’t fuss with her hair, but it’s obvious that they are communicating. Paolo has become our little drone, scouting the city from the air.

“No,” she says at last, blinking her eyes open.

“Are you sure?” I press. “How can you know?”

“I know what Paolo knows. He hasn’t seen him. Or the Children, for that matter.”

“Are we still acting like they’re two different things?” A long line of skin has fallen from the apple that Roe is peeling, almost touching the floor. “I mean, let’s face it. He’s gone back to them, hasn’t he?”

“We don’t know that,” I reply. “We have no proof of that.”

Aaron disappeared after the conversation with Dorey, on the day of Sister Assumpta’s fun

eral. There are only two ways to interpret the disappearance: betrayal or cowardice. It’s hard to know which with Aaron. He was, after all, a master manipulator working on behalf of a right-wing religious cult, which indicates weakness and betrayal. He also had the courage to leave them and to radically reassess his own worldview, which signals bravery, as well as character.

Where are you, Aaron?

The first time we met him, Aaron was mentally torturing teenagers in order to get them to join the Children. Roe and I had a fight then, on the bus home. You guys are two sides of the same coin.

I had flipped out. But it turned out that Roe was right. Aaron and I are both sensitives, both born to safeguard the magic of our respective hometowns, and had both failed at it. The longer I sit with that information, the more it disturbs me. The violence, the callousness, the predatory behavior I had witnessed in Aaron—is all of that in me, too? The only thing that separates us are the meager facts of our own lives: that I was born to a liberal, artsy family who let me traipse around the place with tarot cards, and that Aaron was born to a right-wing Christian family who locked him up as soon as his sensitivity—as well as his OCD—started to show.

I want him to come back, and not just because we need him if we’re going to fight the Children. I want him to come back so he can remind me that we’re different, and I want him to come back so he can reassure me that we’re the same.

“Paolo says that there’s new MISSING posters,” Fiona suddenly says. “Some boy.”

“Who?”

“He doesn’t know. Paolo can’t read.”

The “duh” here is implicit.

“But he can read the word missing?”

“He can intuit it.”

Nuala puts a cup of tea down in front of Fiona. “Where, Fi?”

Fi closes her eyes again. She is gathering a picture, in the same way I gather mine with my telepathy. Worming her way into a bird’s memories, trying to see what he saw, pushing against the limitations of the fact that his brain is

the size of a peanut.

“The writing is all blurry,” she says, “but he’s white. Brown hair. The poster is . . . it’s not in the city, it’s in some village in the countryside. I can see, like, farm stuff in the background.”

Manon has put her book down. “Incroyable,” she says, and means it. Manon is aloof about 80 percent of the time, but whenever she says something in French, she’s being utterly sincere.

Fiona’s concentration breaks at the compliment. I don’t know whether she has told Manon how she feels yet. She hasn’t even told me how she feels about Manon yet, but she knows I know. When you know someone’s brain so well, you can’t help occasionally stumbling into it and picking stuff up.

There’s an awkward kind of intimacy to having a telepath for a best friend: we both pretend I don’t know things, and in that pretending there’s a kind of gratitude. Thank you for not confronting me about my own secrets.

Nuala takes out a notebook and writes down the information that Paolo has shared. “That’s the third in a month,” she says.

“How many missing kids is normal?” Roe asks. “And yes, I realize that is a weird and profoundly tragic question.”

“In Kilbeg County?” Nuala muses. “Maybe a dozen a year.”

Lily turns around. “That feels like a lot.” And she is, of course, thinking of her own disappearance. It was hard for Lily to understand at first that what was a profoundly liberating experience for her was the source of huge trauma for everyone she’s ever known. But she’s grasping it now. Grasping life again, and the emotions that come with it.

“You were an unusual case, Lily,” Nuala says, inspecting the yule boar. “Middle class, white, nice school. You got a lot of coverage. But you know, immigrant communities, Traveler communities, or just very poor kids—we hear less about those kinds of people. And Kilbeg County is big. You’re city kids, so you don’t think about it. But all the townships have their own little issues.”

“So if one kid, on average, goes missing a month,” Fiona says, “we’ve tripled our numbers

in the last thirty days.”

“And still no Housekeeper,” Roe adds grimly.

“And still no Housekeeper,” I repeat.

Then silently, to myself: And still no Aaron.

Chapter 2

hard to take school seriously anymore. First, because it’s only a few days until the Christmas holidays. Second, because there is no school to go to. The fire that killed Sister Assumpta and Heather Banbury also took down about two million euro of real estate, the pristine new refurb that was granted to St. Bernadette’s under the condition it came under Children of Brigid’s control.

The younger years have all been absorbed into different schools, and there’s a general sense that St. Bernadette’s, as a concept, is over. There is no St. Bernadette’s without Sister Assumpta, after all. But at some point it was agreed that the Leaving Cert students, only months from their exams, shouldn’t be exposed to any more trauma. So we all tune in on our laptops every day, cameras off, playing out the end of our schooldays alone in our bedrooms.

Roe drops me home at nine, giving me a long kiss from the driver’s seat.

“Oh, Maeve. Whatever will I do now?”

I smile, leaning in. “Well, gosh. I can’t think.”

“Drive around, I expect. Get into a switchblade fight in a car park.” He raises an eyebrow, a pantomime James Dean.

“Getting yourself into all kinds of trouble.”

“All kinds of trouble,” Roe repeats, sliding a hand underneath my sweater, fingertips cooler than rain.

“I guess I’ll see you . . . when I see you.”

Roe smiles. “See you when I see you, Chambers.”

We are smiling because we love each other, and we are smiling because we have a secret.

I go inside. I talk to my parents. They are frightened of me now. The fact that I was there when the fire happened, that Sister Assumpta inexplicably left the school building to me, and that several journalists have been in touch about doing a story around the Famous Witch of Kilbeg has alienated them to the point that they don’t know how to speak to me. Can you blame them? I used to be the black sheep of the family. Now I’m the Black Death.

The siblings will

be home in a few days, so we talk about that, and then I say that I’m tired. And then I go upstairs.

I go into the bathroom, the one that Aaron said was now a magical hot spot and might wreak havoc on the next people who live here, and I start my spellwork.

I came home one day, a week after Sister Assumpta’s will reading, and all my magic books were gone. My crystals, my tarot collection. It would have been more upsetting if I hadn’t known it was coming. My parents had been thinking about it for days, as the newspapers kept circling around the story of the lucky girl who inherited a fortune.

I siphoned off the valuable stuff well in advance—the good ingredients, the powerful crystals, my one really important tarot deck—and hid it all in a shoebox in the ceiling tiles of the bathroom. What my parents have confiscated are the spell books, some stuff on Wiccan theory and magical history, a random book about pagan myths. I don’t need any of it. I can make up my own spells now, and I’m pretty good at it.

I pour chamomile blossoms and lavender sprigs into my palm. Weirdly, sometimes I find myself narrating my own process, like I’m one of the authors of the spell books. “Chamomile flowers,” I say in a singsong voice. “Available cheaply in any health food store!”

My thumb is wet with rose oil. I crush the mixture into a pulp, grains and stems grinding under my nail, stabilizing my palm by pressing down on the knuckles. I feel like I’m about to drive a hole through my own hand. I turn the tap on. “Deep sleep,” I say simply. “Deep sleep, deep sleep, deep sleep.”

The oily flowers swirl around the drain, clogging briefly at the plughole. There’s a burning at the back of my throat, the feeling of magic talking back. I gesture to it in my mind. Hello, hello, I say. You’re here again. I just want everyone to have a nice sleep.

I’m better at magic since the fire. More intuitive, more confident, more capable of calling to something that I can feel but can’t see. “Maybe she’s born with

it,” I murmur to myself. “Maybe she’s a magic teen!”

I can feel a tide of swirling energy, and I can feel it agree with me. It goes down the plughole and into the pipes, and soon the house will hum with cozy peace. My parents, who could not sleep for days after the fire, will rest soundly. An alarm might wake them up, but a front door closing won’t.

An hour later, I leave the house, and I don’t even bother to tiptoe. I go straight to St. Bernadette’s, wrapping my big black overcoat around me. It’s a man’s coat, technically. I would have felt weird about wearing men’s clothes a few years ago, before Roe made me see how weird it is to give fabric a gender. Now I love the drama of this big thing, leaving me snug against the December chill.

The whole building appears as though it’s slouching on the thick ring of scaffolding that surrounds it. An old woman leaning on her crutches. It looks impossible and dangerous to penetrate, with its layers of police tape and boarded-up windows. But we are, it turns out, impossible and dangerous. I climb through, phone flashlight shining out from my breast pocket.

As soon as I’m inside, I hear the sound of an unplugged electric guitar being comfortably played by Ireland’s next greatest rock star. I follow the sound and stumble into Sister Assumpta’s old office, tripping over a pile of rubble that seems to have fallen out of the ceiling.

“Oh,” I say in mock surprise. “Fancy meeting you here.”

Roe looks up from the battered old couch, one of the few things you can still sit on and not come away covered in ash stains. We’ve bought blankets from charity shops to layer over it. Towels from home.

I watch him for a moment. Pale skin, red mouth, black hair.

Delicious delicious delicious.

His eyes follow me around the room, but he doesn’t say anything. Just keeps playing the guitar, fingers picking out a blues scale.

“You know,” I continue

, “this is private property.”

“What’s private,” Roe replies, “between two old friends?”

“You tell me,” I say, and slowly start unbuttoning my shirt. Coat still on.

Would I be able to talk like this, act like this, if we were in the car or my bedroom? I don’t know. But there’s something about this building. Something about knowing that it’s mine.

There’s a click of a space heater, the room filling with stiff warm air. Another thing brought from Roe’s house. I would be nervous of the electrics here if it weren’t for Roe’s gift for them.

There are no buttons left.

Roe speaks again. Throat stuck. Voice warm.

“I think we can go more private than that.”

I let my coat fall to the floor.

There are so many things in my life that I am forced to feel strangely about, but sex, thank god, isn’t one of them.

It can be difficult to find a time and a place. My family hardly leaves the house these days, and Roe is constantly doing something with the band. I imagine plenty of teenage relationships have this problem, and we’re uniquely privileged in that I happen to be the sole benefactor of a giant, empty house. With a giant, empty sofa.

“Has there been any research into the possibility,” Roe says, twirling a length of my hair as I lie on his chest, “that you are the hottest woman in the country?”

“Not nearly enough research,” I reply, tracing a circle on his bare skin. “It’s so hard to find funding for that kind of thing.”

“A real shame.”

“I know. Think of everything we could learn.”

Roe kisses the top of my head.

“You love to accept a compliment, don’t you, Maeve Chambers?”

“Well, I don’t get that many.” I used to be the kind of girl who couldn’t accept a compliment. Now I am the kind of girl who could be dead in a week. I am going to feel as good as I can until then. “Do you think she’s coming?”

“The Housekeeper?”

“Who else?”

“I don’t know. It feels as though we’ve been waiting a long time for this threat to materialize. Maybe she’s dead. Or maybe sealing the Well means that there’s less magic for her to live off.”

It’s not the first time we’ve shared this theory, and now we’ve shared it so many times that it’s become a bedtime story. Something to soothe us, ease us into sleep.

I look up. “You have eyeliner boogers,” I say. “Black eye snot.”

“Ew, get it out.”

Tenderly, I swipe my pinkie finger under his eye, picking up traces of kohl as I go. I show Roe the accumulated grime. “Make a wish. A Christmas wish."

But instead of making a wish, Roe just pulls me closer. Or maybe that is the wish. It’s hard to tell. I lay my head on his chest and try to listen to the quiet. Sometimes I convince myself she’s still here, somewhere. Sister Assumpta, I mean. I don’t always come to meet Roe. Sometimes I come alone, to feel her out.

I tried to explain this to Roe once, and he wasn’t impressed.

“So according to you, we’re boning under the watchful eye of a dead nun?”

“No!” I exploded. “Don’t make it weird.”

“You’re the one who made it weird!”

But I like to think of her here, casually underestimated by everyone, straining hard to protect Kilbeg with the magical strands she managed to weave into a blanket. I close my eyes, focus my brain, and I almost feel like I can connect with her. The sensitivity thread that connects me and Aaron must have also existed between me and Assumpta. I try to access it. I cannot tell if I am experiencing supernatural phenomena or a strange form of delayed grief, but sometimes, I can feel her. A presence. A something.

There’s a sound. A clatter. The sound of a foot going through a floorboard.

We both jump. I grab the blankets instinctively, painfully aware that I am nude except for my socks.

“What the hell was that?”

Roe gets up immediately, pulls on a sweater and underwear. He turns around, takes a look at me. “It’s not the Housekeeper,” he says soothingly. “Her thing isn’t breaking and entering, is it?”

“No,” I reason, still freaked out. “I suppose not.”

Roe’s sweater is emerald green, and so loose that it falls around his arms, exposing a shoulder.

“It’s probably nothing. Come back to the couch,” I say quickly.

“When, in any horror film, has ‘it’s probably nothing’ turned out to be nothing?” Roe responds, pulling on jeans.

Another clatter. The sound is getting closer now, and I’m beginning to regret trying to communicate with Sister Assumpta’s ghost.

“Shit, Roe.”

“I’m going to check it out.”

“Don’t leave me!”

But Roe is already halfway out the door, so I throw on my own clothes as quickly as I can and follow. The space heater ticks and crackles, and I think: If I lose the one nice thing left in my life, I might truly go insane.

Chapter 3

the hallway, I can feel that my socks are caked in ash, dust, and general debris. Little splinters of wood, tiny bits of gravel that have somehow found their way inside.

“It’s coming from upstairs,” Roe says, putting one foot on the stair. He closes his eyes. “Hang on.”

I can see him burrowing down into his gift, talking to the house. The pipes, the wiring. “Hold my hand.”

I lace my fingers through his. He leads us up the rotting staircase, dodging each faulty step, taking his hand off the banister whenever he knows there’s weakness.

“Your hand is shaking,” Roe notes. “You’re not really scared, are you?”

“No,” I say. It is not convincing.

“It’s probably squatters. Housing crisis, you know.”

But Roe didn’t talk to Dorey at the funeral. Roe didn’t see the satisfaction in her eyes, the sense that the package would be all wrapped up just so. There was zero doubt in her voice that day. What if this is it? The end?

“Roe,” I say. “I love you, OK?”

“Huh?”

“If anything happens, I don’t want our last conversation to have been about eye goo.”

“OK, Maeve, I love you, too.”

But there’s another sound, a sound of feet, a sound of furniture being dragged, a sound of movement. I feel Roe’s hand tense. Feel him think: Maybe it’s not nothing, after all.

Up the stairs again. We’re on the third floor now. Memories of doing my geography homework on the landing, notebook propped up on my thigh, minutes before class. Fiona telling me to hurry. That was only seven months ago. Can really so much have changed?

We reach the door of 3A, and there’s no doubt that whoever is in my house is behind that door.

“Hold on,” Roe whispers, looking around. He crouches down next to a defunct radiator

, one of the many radiators I used to spend the winter months sitting on, and runs his hand along the thin copper pipe fixing it to the wall.

“Come on, sweetheart,” he whispers. And the pipe, swooning, comes away in Roe’s hand. He examines it, focuses on it, and slowly it bends into the shape of a crowbar.

“Did you just make a weapon,” I whisper back, “out of a radiator pipe?”

Roe shrugs like it’s nothing. “Come on, then.”

And, with his hand on the door, he opens up 3A.

We don’t see anyone at first. But what we do see is this: a sleeping bag, a backpack, and a camera. The camera throws me. It’s a Polaroid, but one of those updated Polaroids they started making a few years ago and that girls sometimes take to parties. It confuses me, but Roe’s thought pattern is instant, clear: Why has someone brought a camera to a place where I have sex with my girlfriend?

A strange mix of terror, relief, and disgust washes over both of us. Oh, I think. It’s just a pervert! A run-of-the-mill pervert. Not a revenge demon. Well, that’s something, isn’t it?

Then a voice. A familiar one.

“Roe?”

I whirl around, and Aaron is standing by the window, partially obscured by what’s left of the curtains. I don’t know why he says Roe’s name first, or why he sounds so confused. But Aaron’s here, and I feel a release, as though I’ve just found my passport.

“What the hell?!” I say. “Aaron?!”

Aaron is hanging out the window, smoking a cigarette. There’s some scaffolding that he is half balancing on, a pole he is leaning his back against. His hair is buzzed short, his eyes tired. He’s lost weight. He didn’t have very much of it to begin with. I can see the frame of his face much more now, the bones of his cheeks jutting slightly.

“Dude,” Roe says, already picking up the camera, “what the hell?”

“Put that down,” Aaron says, far too fiercely.

“Why are you sneaking

around St. Bernadette’s? With a camera?”

It’s the emphasis on the word camera that throws Aaron slightly, and he pauses to take us both in. Then he realizes that we’ve clearly dressed ourselves in a hurry.

“Wow,” he says dryly. “I didn’t realize I was interrupting the fall of Sodom and Gomorrah. Why are you carrying a copper pipe? Are you going to beat me to death with it?”

“Jury’s out,” answers Roe, still holding the pipe.

“Oh, for god’s sake, what are you doing here?” I ask. “And where have you been?”

Aaron looks at me oddly then, cigarette hovering in front of his face. His eyes go between me and Roe, and back to me again.

“Around,” he says at last. “I’ve been around.”

Next to the sleeping bag is a black plastic sack of clothes and a small backpack with a zipper open. I can see a can of deodorant, some shower gel, a razor. “Aaron, have you been sleeping rough?”

“I’ve . . . not been sleeping soft.”

“So, what, you’ve been around the world and now you’re crashing here?”

He squints at me, as if trying to figure out my game. As if I’m the one talking in riddles. It’s too frustrating. I can hear my voice taking on a high, manic tension, the tone of someone who might cry if she doesn’t scream.

“You’ve had us all sick with worry, Aaron, and we’re all terrified of this Housekeeper stuff as it is. The least you can do is tell us why you left.”

“And why you’re back,” Roe adds. “With a camera.”

Roe moves toward it again, brows furrowed. Aaron steps away from the window.

“Don’t touch it, Roe.”

His voice is low, with a hint of his old fundamentalist condescension. That tone of I know better than you do, kid.

“Why?” Roe snaps. “ W

hy don’t you want me to touch it?”

I’m struggling to understand why Roe is so interested in the camera. Even on his worst days, it’s hard to imagine Aaron snooping around, spying on us. But then I realize that the new-old Polaroid camera is giving off a frequency that only Roe can read. In the same way I can see people’s colors, Roe can see some kind of charge in the air, strange atoms that are sluicing off this tiny machine.

“Just don’t, OK?” Aaron says, almost threateningly. “Just don’t.”

“Why are you here?” I stress, trying to get back to the matter at hand.

Roe is moving closer to the camera, and it’s like watching two siblings in a turf war over a shared bedroom. Aaron is twitching, like he’s about to spin out.

“Oh, for god’s sake, Maeve, you know why I’m here. I’m here because you sent me the note.”

“The note?” I’m deeply confused by this.

“The note?” Roe says, horrified. And finally, they forget about the stupid camera.

“What did it say?” I ask, carefully assessing my memories, checking for any note-sending. When Heather Banbury was draining my magic, my movements were so fuzzy and hard to remember. Could some of that sickness be hanging over still, without me realizing? ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...