- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

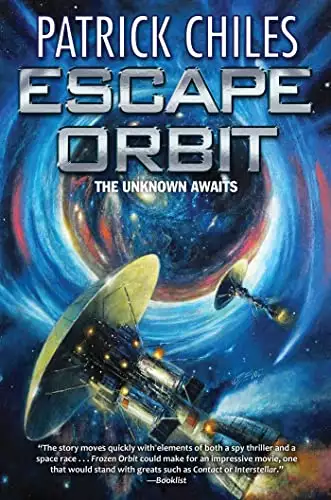

A RACE AGAINST TIME AND A GATEWAY TO THE UNKNOWN AWAITS

Thrilling space adventure from a Marine vet.

Five years ago, astronaut Jack Templeton took the spacecraft Magellan to the farthest reaches of our solar system, never to be heard from again.

Until now.

When the Magellan suddenly reappears where an undiscovered planet was suspected to be, it poses more questions than answers. How did Jack survive all this time? Can he be rescued before his life support runs out? And what is the object long thought to be the elusive "Planet Nine?"

In a race against time, Jack's former crewmate Traci Keene spearheads a desperate effort to outfit a rescue mission. But she has competition. Agencies of both American and foreign governments have their own agendas, and rescuing rogue astronauts isn't among them.

And at the edge of all that is known, a gateway to the unknown awaits . . .

Release date: April 4, 2023

Publisher: Baen

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Escape Orbit

Patrick Chiles

1

Light.

Cold and clear, it sliced into his subconscious like a scalpel, severing the black veil that had blanketed his mind for so long.

Sound.

All competed for his attention at once, a cacophony in his head seeking equilibrium until it eventually settled into a reassuring background hum.

He could see, and he could hear. He basked in the light and sound, taking comfort in the return of outside sensations. He sensed his subconscious mind commanding his limbs to move, his fingers to touch, but they could feel nothing. He decided that just being awake was good enough. The rest could wait.

That was what he hoped for, while a burning question tore through his silent contemplation: Am I home?

No. Though he could not yet smell or taste or touch, wherever he was this place was too clean. Antiseptic. Home was warm, comfortable, with a just-right level of messiness. Wherever he was now, it was too much like a hospital.

The memories came in a trickle, disconnected and chaotic. He had to sort through them, resolve them into a construct that made sense. Maybe once he figured out where he was . . .

“Hello, Jack.”

“Yes?”

“How do you feel?”

The voice came from everywhere and nowhere. Gentle, precise, and feminine. “Traci?”

“I am not Traci. You named me Daisy.”

“I named you?” It took a minute to register. “Wait . . .” He remembered: Distributed Artificial Intelligence Surveillance Environment. DAISE.

Daisy.

His mind exploded with more vaguely connected memories that flooded his stirring consciousness like an overflowing dam, just like the voice he perceived to be everywhere at once, yet nowhere. As the swirl of light resolved into more familiar patterns, what he could perceive was equally strange: crystal clear yet distant, as if he were looking through someone else’s eyes.

This wasn’t home, and it wasn’t a hospital. He was still aboard the spacecraft Magellan, speeding toward the outer edge of the solar system, looking for—what, exactly? Why did he have no recollection of that?

Because we didn’t know what we’d find, he remembered at last. His last memory was of reclining into an emergency medical pod, hooking up leads and self-administered intravenous lines while nervously waiting for Daisy to inject the neural implants and administer the first round of sedatives.

Torpor. Hibernation. Suspended animation. Different terms for what amounted to the same condition: slowing his metabolism to a fraction of its normal rate, keeping his body in a state that would require the minimum amount of energy both in terms of power for the ship and calories for his body. Each was limited and precious, calories acutely so.

As he slept, Daisy was to guide them billions of miles from home, beyond the Kuiper Belt. Looking for—what? Life?

Yes. No. Maybe. A planet, that’s what they were searching for. Their agreement had been for Daisy to wake him either when they found it or when their orbit brought them back to Earth. The first milestone was going to take a couple of years. But coming back to Earth? The last calculation he remembered before pushing the everlasting snooze button was that it would take a long time indeed: the better part of a decade, given their remaining propellant load. There’d been no way to be sure, not until they knew their final state after arriving at Planet Nine—assuming the place existed and they hadn’t embarked on a cosmic snipe hunt.

“Planet Nine” had been the popular name given decades earlier to the theorized planet, a placeholder for a world that had to exist. There was too much evidence of a Neptune-sized gravity well lurking out there, perturbing the orbits of dozens of dwarf planets over the ages, each pointing in the direction of the elusive body that had drawn

them out. Added to his crewmate’s discoveries at Pluto, it suggested that the Kuiper Belt harbored an astounding mix of undiscovered worlds and complex organics that may well have combined into the first living organisms on Earth. A trail of crumbs, leading to . . . what?

It was too much to process, yet it was all there demanding for him to do just that.

“Where are we?” he asked warily. His voice did not quite feel like his own yet. “Back at Earth?”

“No.”

That was something of a relief. He’d been mentally prepared for two years in the Big Sleep, but that didn’t mean he’d been looking forward to it. “A little more specificity would be nice,” he muttered. “Have we found Planet Nine?”

“We successfully entered orbit around a gravitational anomaly at the predicted location, though it would be better if we discussed the specifics later. How do you feel?”

“Strange. I can hear you, but I can’t feel anything yet. Can’t focus on anything either. Seems like I lost my sense of smell, too.” The side effects of long-term hibernation, he assumed. “Are you in contact with the control team?”

“We are transmitting telemetry again. I was waiting for you to dictate a message.”

Again? he wondered. Had they dropped out at some point? Too many questions. “Fair enough. So what can you tell me about our mystery planet?”

“In time. There is much that you need to know.”

Human Outer Planets Exploration (HOPE) Consortium

Grand Cayman

Owen Harriman had long ago become accustomed to absurdly long hours as a mission manager. When he’d been with NASA, it had often been due to unexpected developments which had an annoying tendency to emerge late in the day or in the middle of the night. As they’d always involved trouble with crewed spacecraft in flight, he’d not had the luxury of putting things off until morning. Ignoring glitches could mean mission failure or worse. Crew loss events squarely landed in the “or worse” column.

His tenure with the HOPE program had not altered that equation, though it had led to a drastic change in scenery. The consortium’s prime benefactors, aerospace magnate Arthur Hammond and asteroid mining pioneer Max Jiang, had determined early on that the best way to protect their joint investment would be to “offshore” its management, keeping the newly privatized Magellan team away from the direct reach of a government that was,

in Hammond’s memorable construct, increasingly behaving like “bipolar kleptomaniacs.”

The shift from NASA to private employment had been jarring enough—being rewarded for not spending all of his annual budget, versus the government model of losing funds if he didn’t spend every last allocated dime, had been the first of many shifts in his perspective.

Not having a crew in the sense that he’d been accustomed to had been the other. Jack Templeton’s hair-raising slingshot burn to the edge of the solar system and immersion into hibernation had been a trial by fire, as it had occurred during the handover from the space agency to the HOPE consortium. Houston’s mission control center had been filled with fresh-faced technicians from Hammond’s and Jiang’s companies, all learning the ropes from Owen’s long-serving team of flight controllers.

To their credit, they’d been smart enough to recognize the steep learning curve ahead of them despite the similarities to their commercial space jobs. Running orbital supply missions and lunar mining shipments was a lot different than managing a nuclear-powered deep space vehicle where signal return times were measured in hours—a controller’s entire shift could pass just waiting for a response to a query. It hadn’t hurt that a sizeable percentage of Owen’s team had seen the writing on the wall themselves and jumped at the opportunity to keep Magellan going as a private venture.

Once they’d completed the slingshot and a final course correction, Jack had gone to sleep. More properly, he’d allowed himself to be placed in torpor as his ship raced toward a destination that no one was certain would actually be there. To many it was seen as a death sentence, a delayed-reaction suicide.

Owen knew Jack better than that. He’d seen no other way to conserve enough resources to get the rest of his crew back to Earth alive. Someone had to draw the short straw, and he’d been determined that it would not be for nothing. What they’d found in the Kuiper Belt had been tantalizing, a trail leading to a destination that was long suspected but never found. The phantom planet was out there somewhere, a body ten times more massive than Earth, with a growing cluster of trans-Neptunian objects pointing toward its gravity well like weathered signposts along a forgotten roadway. And he’d taken Magellan on a hell-for-leather slingshot around Venus and then Jupiter to find it, using their gravity to accelerate and bend his trajectory into unknown territory.

To survive the trip, he had been in hibernation for longer than anyone had ever endured. He hadn’t quite been alone, with Daisy watching over him like a computerized mother hen as she did for every other function of the ship. Jack Templeton had become just one more system for the AI to monitor.

If he were honest, Owen had to admit Daisy had been the source of too many sleepless nights. His prior routine had been constructed around human astronauts and their need for rest, but the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Surveillance Environment had no such constraint. Daisy was fully functional 24/7. Even the occasional software pat

ch first went to a partitioned server that didn’t take her offline for a second. Daisy was pilot, engineer, observer, communicator, and nurse. She had kept the former crew’s practice of transmitting twice-daily situation reports as if she were a live crew member, not satisfied with limiting herself to robotic telemetry streams.

That was how it had been until five years ago. As Magellan should have finished decelerating into the elusive Planet Nine’s gravity well, it had without warning gone dark after sending a single, enigmatic message:

HAVE ENCOUNTERED GRAVITATIONAL ANOMALY AT PREDICTED LOCATION OF PLANET NINE. ESTIMATE MASS 1.03 X 10^26 KG.

UNABLE TO DIRECTLY OBSERVE. MANUEVERING CLOSER TO INVESTIGATE. WILL UPDATE AS ABLE.

TEMPLETON OUT.

There’d been no further voice comms or text messages, no telemetry, no infrared signatures from the ship’s powerful fusion engines. Repeated sweeps by the Deep Space Network’s array of sensitive antenna dishes had repeatedly come up empty.

All of this had changed at 3:16 A.M. In truth it had been some time before then, but that was when Owen’s phone had started bleating at him from his bedside table. To their credit, the overnight shift had waited until they’d collected enough data to digest and build a picture of what was actually happening forty billion miles away before waking him up.

Still clearing the mental cobwebs, Owen pulled on a fresh polo shirt and a pair of worn jeans, splashed cold water across his face, and combed the thinning remnants of his wavy blond hair. It hid the encroaching gray rather well, he thought.

He brushed his wife’s forehead with a kiss and looked in on their sleeping children before padding across the ceramic tile floor and out the front door. As he drove along a twisting road that led from his family’s bungalow to the HOPE complex, he considered the unlikely situation Jack must be finding himself in.

Few had expected him to find anything. To many his actions had seemed like desperation, a way to rationalize the certain death he’d volunteered for. For his sake, he’d damned well better have hoped there was a sizeable gravity well out there because it offered the only chance he’d have to bend his trajectory enough to keep from zipping out into interstellar space. Their weeks-long braking burn had suggested they in fact hadn’t been aimed at a blind spot in space—gravity from a massive object had been acting on them, bending Magellan’s path toward it just as they’d predicted, right up until all traces of the ship had disappeared.

It was an impressive feat of navigation with no small measure of blind courage, and after putting it all in motion he had been forced to sleep

through the whole thing. It was a minor miracle that he’d survived so long in what was essentially an induced coma. By now his muscles could be atrophied beyond repair and his brain turned to oatmeal. Owen shuddered at the thought: The gregarious, outdoorsy wiseacre he’d known might well have become a shriveled up husk, aged well beyond his years despite his hibernated state.

Did it work like that? Owen wondered. He couldn’t know for certain as no one had ever done it for this long. For all they knew, years of suspension during cruise might have left him rested and ready to take on whatever he encountered. Perhaps there was some asymptotic limit to how much the body deteriorated in microgravity, and he’d end up just fine after some physical rehab.

Who am I kidding? Jack was on a one-way trip, fanatically looking for more clues to life’s origins after their discoveries at Pluto. His dizzyingly fast outbound run had only been possible because of the mass he’d shed flinging his crewmates Earthward, taking an excursion craft and half of Magellan’s remaining logistics modules with them. After using the ship as a giant nuclear-powered catapult to save his friends, he’d then turned what remained into a stripped-down speed machine, reasoning that he might as well accomplish something with the tools at hand.

Such were the thoughts swirling through Owen’s mind as he made his way into the control center. A half-dozen technicians hovered over a row of consoles, only one of them acknowledging him. The shift leader handed him a cup of fresh coffee.

Owen closed his eyes and cradled the mug in his hands. “Bless you, Jerry.”

“There’s plenty more where that came from. Need a minute?”

He took a sip and eyed the monitor beside him. “I’m good. Let’s get right to it. What did you see first?”

The engineer stretched and rubbed at his eyes. “That’s a good question. Now that we’ve got hard data again, I think we first saw it two days ago.”

Owen leaned forward. “Okay, now I’m awake. How’d we miss that?” he said, careful to avoid the accusatory you.

“Once this stuff came in, it made me wonder why it took so long. I’d say we went looking for weird transients in the data stream, but there was no data stream.”

“Now you’ve lost me. If there was nothing to see, why do you think something got missed?”

“It’s not that there was nothing to see. We just weren’t looking in the right place. We were waiting for fresh telemetry after all this time of searching empty space.”

Owen nodded, not sharing the thought that if Hammond wasn’t already moving a good piece of his operation to Grand Cayman, all of them might have been out of jobs by now. “So what did you look at?”

Jerry pulled up some grainy images and tables of spectroscopic data. “Electromagnetic emissions in the predicted vicinity of the starship, beginning day before yesterday.”

Owen did a double take. “Starship? Is that what we’re calling it now?”

“We figured let’s call it like it is. If it didn’t slow down—”

“I get it. He’d be at

Alpha Centauri in another century or so.”

“In that direction? More like Epsilon Eridani in five.”

Owen frowned. “Point taken. Go on.”

“Like I said, EM activity. Faint. We thought it was just transient noise, maybe an uncatalogued satellite in the same slice of sky or a cosmic ray burst spoofing our signal processors. We didn’t associate it with Magellan because there wasn’t anything else to support it.”

Owen pieced together what he was hearing. “So no drive plume, then?” That would have been a dead giveaway.

He shook his head. “Nothing. But the radio noise didn’t go away either. After a while we were able to detect a slight doppler shift in the signal, like its source is orbiting something.”

“Were you able to identify a barycenter?”

“Rough order approximation, but that’s just it—nothing’s visible. There must be a gravity well because the doppler is a steady period. We clocked six hours and change.”

That was an awfully tight period for something orbiting a planet suspected to be the size of Neptune. Owen rubbed at his eyes with the heels of his hands. “Okay, I see how we might have missed that at first. Have you reached out to any of the radio observatories yet? Any chance someone else picked it up?”

“Always possible, but we haven’t talked to anyone else. We’ve still got a lot to go through. Once we isolated the signal, it turned into a massive info dump.”

Seeing the activity surrounding the other consoles, Owen could tell the controller wasn’t exaggerating. “What do you have so far?”

“Years of missing trend lines, for one. Looks like there was a power loss we didn’t see coming. Daisy diverted a lot of juice to the medical module, but that doesn’t explain why the ship went dark for so long.”

It didn’t necessarily imply something had happened to Jack, but it still didn’t sound good. “Round-trip signal delay’s on the order of what, sixteen hours?”

“Correct, but we haven’t transmitted anything. Just trying to understand what Daisy’s telling us for now.” The lead controller inclined his head toward the communications console. “There’s more.”

Owen looked over the comm officer’s shoulder at an open message window. As he read the text, his mouth fell open.

CapCom met his gaze. “Yeah, that was our reaction too.”

“Anybody else see this?”

“Just us, boss.”

Owen opened a binder with contact protocols and lifted the receiver to a secure phone. “Keep it that way for now.”

2

NASA Headquarters

Washington, DC

Jacqueline Cheever was not known for her good humor, particularly when receiving unpleasant news—and the daily conference call with the various NASA center directors under her frequently involved unpleasant news.

Her prior role as the space agency’s Planetary Protection Officer had been in continuous danger of being overlooked by the more jaded managers from the operational divisions, and she had ascended to the top office with a determination that others would take her as seriously as she took herself.

As an evolutionary biologist, Planetary Protection, and by extension Earth Sciences, had been her passion. To her, protecting Earth’s neighboring planets from inadvertent contamination by data-seeking probes was a high calling. Humanity had already fouled its own nest, and she’d been determined to prevent from doing the same to the rest of the solar system. As NASA administrator, Dr. Cheever was in a position to make her priorities everyone’s, if she could just keep them corralled into doing their jobs. It surprised her how often that required intervention.

As the project manager from Goddard droned on about the latest snags in the Climate Change Action Plan, Cheever became visibly displeased, her sharp features exaggerated by the taut bun of her jet-black hair.

“I need to emphasize the CCAP team is meeting all project goalposts,” the portly engineer insisted. “From our perspective, Project Sunshade is on track.”

“From your perspective,” Cheever said, her eyes locked on his. “Yet somehow the schedule keeps moving to the right.”

“As I said, the team is—”

She held up a bony hand to silence him. “Let’s be clear: Your team can’t do anything on its own. That’s a convenient distinction for you, since you don’t control the production or the supply chain.”

“Yes, ma’am, that’s true,” he stammered, forgetting how much traditional gender honorifics annoyed her. “We’re constrained by our contractors—”

“And have you made our expectations clear? It doesn’t seem to me that you have.”

“They have to work with the materials they have on hand, Dr. Cheever. Not to put too fine a point on it—”

“By all means, please do. It would be refreshing.”

The project manager bit his lip. “Very well. Selene Gas & Mineral is the bottleneck.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Max Jiang’s company.” They had never been as committed to the Sunshade project as she’d liked, and now their slowdowns were threatening the entire global cooling program. Cheever was continually appalled at how many in the mining and petroleum industries refused to treat climate change with the urgency it deserved, including the “off-worlders” like Jiang. “Their enthusiasm for this project has always been suspect,” she groused, “even though we were throwing money around like drunken sailors in a strip club. The pigs always find their way to the teat.”

The other directors shifted uncomfortably while keeping their practiced neutral expressions. They all understood the unspoken reason why Jiang had signed on: SGM was the only game in town, and thinly veiled threats to his Earthbound drilling leases from both Interior and EPA had nudged him to the bargaining table. Building a web of sunshades at Lagrange Point 1 required enormous mineral resources and getting them from the Moon was cheaper in almost every sense. But as the project wore on, the iconoclastic Jiang had become ever more skeptical of its goals. As she saw it, his personal recalcitrance was now translating into delays which she would not countenance.

Cheever made a tsk sound and moved on to the next agenda item, this from her own

assistant at the other end of the table. Blaine Fitzgerald Winston had worked for NASA years before, leaving under a cloud to apply his skills to a number of trendy non-governmental organizations. There’d been talk of intelligence breaches which in the end had yielded nothing of substance—which didn’t mean there weren’t any, only that nothing had emerged. In Washington, that could just as easily mean nothing had been allowed to emerge.

The young man had ingratiated himself to her early on, displaying a gift for bureaucratic craftiness that she found more valuable than a dozen technocrats. Brilliant engineers were a dime a dozen at NASA; give her an aide who could navigate the byzantine maze of proposals and appropriations any day. Best of all, the young man had tons of connections, an ear for insider gossip, and the brains to keep things to himself until it mattered.

For these reasons, she’d taken the unusual step of making him her personal liaison for the space agency’s most ambitious project, the Great Filter. Primarily funded by concerned tech moguls, the scheme to place a network of sunshades at L-1 would be even farther behind were it not for the pressure those NGOs brought to bear. Diminished economic status or not, getting the United States to lead the world in addressing climate change once and for all was key to the project’s success.

Cheever pointed to Winston, his bright tie accenting a mop of curly hair that contrasted with his otherwise conservative, standard-issue Washington suit. “Go.”

The young man cleared his throat. “I must emphasize this information is confidential, and must not leave this room.” His body language suggested he was uncomfortable with the information he was about to present. In reality, he was anything but. “The Currents Foundation and Global Action Project have a different perspective on solving CCAP’s supply chain issues.” He paused for effect. “They don’t see it as either logistics or engineering; in fact I think we all recognize it’s a question of SGM’s management commitment. To this end, they are launching a coordinated PR campaign that will coincide with Selene’s next shareholder meeting.” He effected a satisfied smile. “If this doesn’t prod Mr. Jiang into doing the right thing, the Securities and Exchange Commission is prepared to investigate his activities.”

Cheever smiled to herself. If the NGOs couldn’t change his mind economically, the market regulators would do so legally. Either way, Jiang would be brought onboard. If all else failed, they always had the threat of Congress nationalizing his business for the public good. One man’s recalcitrance would not be allowed to doom the planet.

“Very good, Blaine,” she said, making it obvious that he was the sole presenter to escape her scorn. “Is there anything else?”

“Just some administrative loose ends with another contractor, which I believe we can tie up soon,” he said nonchalantly. “They’re not germane to this meeting, ma’am.” It was his way of letting her know he had something big for her.

“Same time tomorrow, then,” Cheever reminded the others, and closed the meeting. The room’s holographic screens went blank and she waited for Winston to ensure the conference phones were all off. “Clever wa

y of mentioning the HOPE gang without actually mentioning them,” she said, and gave him a “get on with it” look. “What are they up to?”

Winston removed a folder from his briefcase and pushed it across the table to her. “They’ve reestablished contact with Magellan.”

Cheever paused as she reached for the folder. “It’s been what, five years? Didn’t we have Templeton declared dead?”

Winston seemed uncharacteristically awkward. “That was our official position after his spacecraft disappeared.”

She opened the folder with a raised eyebrow. “What are you holding back, Blaine?”

He smoothed his tie, still somewhat uncomfortable. “Ultimately that’s not something we can control. Templeton gave power of attorney to his sister before he departed Earth, and she refuses to acknowledge the reality of the situation.”

Cheever frowned. “I suppose that is her legal prerogative,” she said with an exasperated sigh. “If big sis doesn’t want to collect the death benefits, then that’s on her.” She flipped through the pages of summaries, her eyes widening as they landed on a particularly surprising passage:

HELLO WORLD. I’M STILL HERE.

TELL TRACI HI.

She looked up at Winston, her face a mask of annoyance. “In this case, she may have been correct.”

Johnson Space Center

Houston, Texas

“You’ve recovered your gross motor skills,” the therapist said. “It’s your fine motor skills that still need some work.”

Traci Keene didn’t have to be told that. She could move around without assistance and had no issues with balance or coordination. She’d even been able to start running again without someone supervising her on a treadmill. The occupational therapists would’ve lost it if they’d known she’d been running on her own, outside on an actual track. “What I need is something more challenging than counting beans or learning different ways to tie my shoes.”

“Still thinking about flying again, aren’t you?”

“Of course.” Why wouldn’t I be? She thought with irritation. “It’s what I do . . . or what I used to do.” What the space agency therapists couldn’t appreciate was just how much of a pilot’s identity was tied up in the act of precisely controlling high-performance machinery.

“One step at a time

,” he said with studied patience. “You’re talking about discrete skills. Eye-hand coordination.”

“I need to be able to reach for a switch and know I’m in the right place by touch and muscle memory. Rapidly. If I have to look down and think about what I’m doing, it’s too late. The airplane’s gotten ahead of me, and that’s when bad things happen.”

The therapist pursed his lips and nodded, resolving an internal argument. “Then let’s try something new,” he said after a moment, and led her to another room. Inside was a chair in front of a desk that held a video game console. Beneath the desk sat a pair of pedals. He handed her a virtual reality headset and a pair of haptic feedback gloves. She slipped them on with a questioning look. This promised to be more interesting than the simple activities they’d had her performing the past several months, but she halfway expected it to be a higher-tech exercise in throwing a ball or sorting blocks.

When the therapist turned on the console, she was elated to see a 3D representation of an aircraft cockpit sitting at the end of a virtual runway. “Cessna 172,” she said with a tinge of disappointment. “I haven’t flown one of these since college. Do you at least have a T-6 in here? Something with a turbine?”

“Small steps,” he reminded her. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...