- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

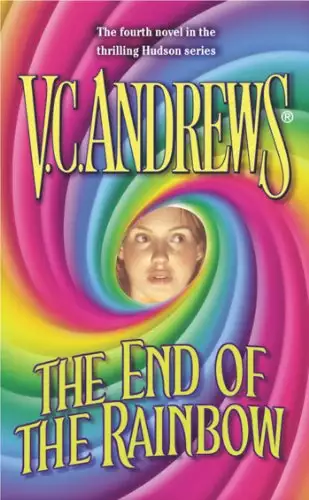

Synopsis

WAS THE HUDSON FAMILY DESTINED TO LIVE IN THE SHADOWS OF THE PAST? OR WOULD LUCK SHINE ON THE NEWEST GENERATION? THE ANSWER LIES AT... THE END OF THE RAINBOW Rain's precious daughter, Summer, is about to turn sixteen. Her future lies wide open before her and she carries her mother's wise advice close to her heart: life is hardship, but above all, life is hope. Like all girls her age, Summer dreams of growing up and making her own life, of falling in love and finding her soul mate. But a devastating tragedy will force Summer to stare into the cold eyes of adulthood long before she is ready. She will learn very quickly about hardship -- but what of hope? Is she as strong as her courageous mother? Or will she crumble? All her life, Summer has lived on the Virginia estate where the Hudson family's secrets have lurked among the shadows for generations. Now it is time for Summer to discover secrets of her own. Some she will keep. Some she will share. Some will force her to flee the only place she has ever called home. And some will haunt her for the rest of her life....

Release date: April 19, 2001

Publisher: Pocket Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

End of the Rainbow

V.C. Andrews

It seemed as if a rainbow had burst over our house and grounds. I knew that Daddy had been secretly planning some surprises, but I was not prepared for all that he had done. The moment the morning sun nudged my eyes open, I heard the gentle tinkling notes of "Happy Birthday to You." With sleepy eyes I gazed at a precious and dazzling merry-go-round spinning a menagerie of animals around a ballerina who danced at its center.

"I hope you always wake with a smile like that, Summer," Daddy said.

I looked up and saw Daddy standing there. His face was glowing almost as much as mine. I had his turquoise eyes, but Mommy's ebony hair and a complexion a few shades lighter so anyone could see that I had also clearly inherited Daddy's freckles, especially at the crests of my cheeks.

"Happy birthday, sweetheart," he said and leaned over to kiss me on the cheek.

Mommy watched from her wheelchair on the opposite side of my bed. For a moment she looked so distant, almost as though she was on the outside of a great glass bubble set around me. I knew she was having one of those Evil Eye thoughts, those fears that whenever she was too happy, something terrible would happen. She seemed to realize it herself and brightened quickly into a smile. I rose to hug her.

"What were the two of you doing?" I cried as the merry-go-round continued. "Sitting here waiting for me to wake up? How long have you been here?"

"We were watching you all night," Daddy joked. "We took turns, didn't we, Rain?"

"Practically," Mommy said. "Your crazy father has been acting as if this was more his birthday than yours." She jokingly put on a look of disapproval. "More and more these days, he acts like a sixteen-year-old."

"You never lose the child within you entirely," Daddy assured us. "I want to blow out candles on my ninetieth birthday and unwrap presents. Don't forget to arrange for that, you two," he ordered, sounding like it was just around the corner.

Mommy shook her head and smiled at me as if the two of us were allies forced to tolerate another foolish man. Daddy could never be a foolish man to me, never, ever, I thought.

"It's a beautiful merry-go-round," I said as it stopped.

"That," my mother said, "is not even the tip of the iceberg. Look out the window," she urged me.

My room overlooked the lake. Grandmother Megan told me it had once been her room, and Mommy said she used it when she had first arrived. Now, she and Daddy used what was Grandmother Hudson's room, only they had changed the decor and replaced all the furniture. The bathroom had been updated to provide for Mommy's special needs.

In the beginning Mommy didn't want to make dramatic changes in the house. She said she felt an obligation to Grandmother Hudson's memory to keep it close to how it had been, but in time rugs wore, walls had to be repainted, fixtures replaced, appliances changed, and Daddy brought in a decorator to give it all what they called a more eclectic style.

The hallways still had the spirit of the nineteenth century with some Federal antiques, like a White and Dogswell clock that hung across from a circular mirror of that period. Mommy was very proud of all the antiques left by my Grandmother Hudson. Mommy had loved her very much, so much that I was jealous and wished I had been able to know her, too.

ard

Grandfather Hudson's office was the same as it had always been, but much of the rest of the house -- the living room, the kitchen, my bedroom and Daddy and Mommy's -- had been modernized with lighter colors and softer fabrics. Recently my parents had redone the maid's quarters, covering the floor with a thick white shag rug and replacing what had been a hospital bed with a queen-size cherry wood one; this pleased Mrs. Geary very much.

After Glenda had married Uncle Roy and she and Harley had moved out of the main house, Mommy and Daddy hired Mrs. Geary through an agency. She was in her early forties at the time and had come from Ireland to live and work in America when she was in her late twenties. Now streaked with gray, her hair had once been almost as red as Daddy's. She had been working for her distant American relatives who she said treated her as badly as Cinderella's stepmother treated Cinderella.

"There was no respect. Everything I did was simply expected, too. Not an ounce of gratitude! I was glad to get out of there," she told me.

Daddy said he liked her because she had an inner strength and confidence he thought would make her an asset in a household where the mistress was disabled. Mommy and she took to each other immediately, and by now it was impossible for me to think of her as anything less than a member of our family. She was often a second mother to me, ordering me to dress more warmly or eat better. She even had something to say about where I would go and with whom I would go. A mother hen didn't hover over an egg as much as Mrs. Geary hovered over me as I grew up under both her and Mommy's wings.

"I spent almost as much time and energy as your mother keeping you growing healthy and strong, and I'm not about to see my investment go sour," she told me if I complained. She loved to find words and expressions to avoid expressing her true feelings for me. It was as if she believed that the moment you told someone you loved her, you lost her. I would learn that her own early childhood and teenage years were filled with enough loss to make her think this way.

Nevertheless, I teased her whenever I could, especially about her endless ongoing romance with Clarence Lynch, the librarian at the municipal library. Like her, he was in his late fifties. They had been seeing each other socially for as long as I could remember.

Once, when I asked her why she had never married him, her reply was, "Why would I want to ruin a perfectly good relationship?"

It confused me, of course, and I ran to Mommy with questions. She simply smiled and said, "Summer, not everyone fits so neatly into the little boxes society has created. As long as they're happy, why ask them to change?"

In Mommy's mind, and I now think mine too, happiness and health were two sides of the same coin, the most important and valuable coin. People who were happy had more hope of being healthy; of course, people who were healthy were happy. Smiles and laughter were the best medications for the illnesses of the spirit.

No one illustrated this better than Daddy, I thought. He loved Mommy and me so much and was so happy that anyone could see him and feel him radiating with warmth and well-being. He was still a highly respected physical therapist who had assumed his uncle's therapy business and then had created a chain of unique health clubs that combined regular exercise with therapeutic programs. They were known as rejuvenation clubs; their theme was that through exercise and meditation aging could be slowed down and even in some cases reversed. National health and exercise magazines had even featured Daddy in articles. I was very proud of him and so was Mommy.

Yes, happiness and health were truly the twin sisters my family had adopted to live beside me. They nurtured wisdom and wove a protective wall around our house. Nothing terrible from the outside could hurt us, I thought. But what I also knew was trouble loomed nearby in Uncle Roy's sad and dour world, and it also came riding into our fortress in the form of a Trojan horse named Alison, my Aunt Alison.

"People who don't like themselves can't like anyone else," Mommy once told me. "Your aunt Alison hates herself. She just doesn't know it or want to know it. I feel more pity for her than I do anger, and you will, too," Mommy predicted.

Aunt Alison, as well as Grandmother Megan and my stepgrandfather Grant Randolph would all be here today for my birthday party.

Now in the morning light, I stood by the window and parted the curtains as Mommy had directed. For a moment I thought I was still dreaming. My mouth hung open.

All of the trees below had been strewn with bright colored ribbons. Many branches had balloons tied to them and they were all dancing to the rhythms of the breezes. Tables covered with green and red and yellow paper tablecloths were all set up on the lawn, and a dance floor was being laid out as I watched. There was even a small stage for musicians.

Daddy had kept my party arrangements a big secret and had obviously paid people extra to come quietly on the grounds very early in the morning, before the sun was even up, to begin constructing it all.

"Your father was out there in the dark with a flashlight hanging balloons," Mommy told me.

"I thought it would be more fun to wake up to it than see it happening days before," he commented from behind.

I still had trouble finding my voice. Finally, I shook my head and shrieked with joy.

"It's...beautiful!"

I rushed into his arms to kiss him and then hugged and kissed Mommy who couldn't stop laughing at my excitement.

"Is your father crazy or not?"

"NO!" I cried. "He's wonderful!"

"You see," Daddy said, "at least I have one woman in this house who sees sense in the things I do."

"You poor outnumbered man," Mommy teased.

"Well, you should have heard Mrs. Geary mumbling how it was all too much of this or too much of that and how even happy shocks can be damaging to a young, impressionable spirit."

"Don't make fun of her," Mommy softly chided.

"Make fun of her? It's everyone else who's making fun of me. All right. I've got some small matters to look after, such as the parking arrangements. I don't want any of Summer's teenager friends driving their cars over the flowers," Daddy said and left.

Mommy shook her head and smiled after him. Would I ever find anyone I loved as much and who loved me as much as my parents loved each other? They were living proof that there really was such a thing as soul mates.

"You'd better get yourself dressed and come down to breakfast," she said turning back to me and starting away.

"I'm too excited to eat, Mommy."

"If you don't, Mrs. Geary will single-handedly rip every balloon off every tree and pack up the tables and chairs," she warned. We laughed.

I hugged her again.

"Happy, happy birthday, Summer. All your birthdays have been special to me because it was truly a miracle for us to have you," she said softly, "but I know how special this one is for you."

"Thank you, Mommy."

I knew how true that was, how difficult my birth was for her and how they had decided not to try to have any more children and test their good luck.

"I'll see you downstairs," she said and continued to wheel herself out to the chair elevator that would take her down the stairs and to the wheelchair below.

Never in my life had my mother ever stood on her own beside me. Never had we walked side by side or ran together. Never had we gone strolling through department stores or down streets to window-shop.

When I was old enough to push her, I thought it was fun. After all, I was a little girl moving my mother along. But somewhere along the way, I turned to watch other mothers and daughters walking through malls, and I looked at Mommy's face and saw the longing and the sadness and no longer did I feel excited or amused by it.

Was that what growing older meant? I wondered. Losing all your illusions?

If that was so, why were any of us so happy and so willing to blow out the candles?

Mrs. Geary milled about the breakfast table longer than she had to, studying me eat as if my consumption of food was part of some important experiment.

"It's a big day," she preached when I complained about being given too much. "Big days require bigger fortification. I know what's going to happen out there after the festivities start. You won't eat a thing and you'll be going, going, going -- draining and draining that wisp of a willow of a body of yours. That's when sickness comes knocking on the door anticipating a big fat welcome."

Mommy looked down at her dish of grapefruit slices, hiding her smile.

"I'm not a wisp of a willow," I protested.

After all, I was five feet four and nearly one hundred and fifteen pounds. Mommy told me I had a figure like hers once was, although I didn't need to be told. I saw the pictures of her when she was in acting school in London. In all of the photographs, she looked like someone just caught the moment after a wonderful new experience or sight. Her face glowed. There was no better compliment for me than to be compared to Mommy.

Mrs. Geary always came in the backdoor with her flatteries, especially about my looks and figure.

"Nature plays a trick on young girls," she informed me. "Before you have a woman's mind, you get a woman's body. It's like putting a diamond necklace around the neck of a four-year-old girl. She has no idea why everyone, especially grownups, are staring at her and she doesn't know yet how to wear it or carry it."

"Young people are different today," I insisted when she made these speeches at me. "We're far more sophisticated than young people were when you were my age."

"Oh please," she cried, slapping her hand over her forehead. It was her favorite dramatic gesture. I actually heard the sharp crack of her palm on her skin. "More sophisticated? You have more teenage pregnancies, more children in trouble with drugs, more car accidents, more runaways.

"When I was your age, the only pregnant girl in the village was a girl raped by her idiot stepbrother."

"Mommy!" I'd moan in desperation.

"She's only trying to give you good advice, honey," Mommy said, but she gave Mrs. Geary a look that said, "Enough."

"I'll eat at my party," I promised. "Daddy's having them make all my favorite things."

That was a mistake. I knew it the moment the words slipped past my lips. Daddy had hired caterers even though Mrs. Geary said she would prepare all the food. He insisted it was an unfair burden to place on her, but she countered with a surprising admission that preparing the food for my birthday was a special pleasure for her. In the end she was given the responsibility for the birthday cake.

She grunted at my statement and shook her head. Occasionally, Mrs. Geary would go to a stylist to have her hair cut and shaped, but most of the time, she wore it pinned back in a severe bun. For my party, however, she had surprised us all by having it cut and trimmed in a French style. She had pretty green eyes and a small nose and mouth but a chin that disappeared too quickly. At five feet seven, she was somewhat portly with heavy arms and a robust bosom. She did have a very soft complexion with not even a sign of an impending wrinkle, something she ascribed to keeping makeup and rough soap off her skin.

"Manufactured food," she muttered with disdain. "It'll have a mass-produced taste."

"Now, Mrs. Geary," Mommy gently chastised. "You know it's not manufactured food."

Mrs. Geary bit down on her lower lip, shook her head and went into the kitchen. Mommy smiled at me and said Mrs. Geary would be fine.

I gobbled down the remainder of my breakfast, too excited to sit a moment longer.

Daddy was outside working with the grounds people to be sure everything was set up the way he wanted it to be. A little more than two dozen of my girlfriends from the Dogwood School for Girls and almost twenty boys from our sister school, Sweet William, would be attending as well as some of my teachers and, of course, my family and Mrs. Geary's Mr. Lynch.

I didn't think of myself as going steady with anyone, but I was seeing Chase Taylor more than anyone else. I had gone on dates with him the last four weekends in a row, and it only took two consecutive dates with the same boy for the girls in my school to have someone practically engaged. I knew almost all my girlfriends envied me. Chase was handsome in a classic way with his perfect nose and sensual lips. He had eyes that could have been the inspiration for the blue sky on a perfect spring day. Daddy approved of him because he was very athletic, six feet two with what Daddy called football shoulders and a swimmer's waist. The truth was he played halfback on the football team and was the record holder for Sweet William's freestyle stroke. He was even thinking of trying out for the Olympics.

Chase's father, Guy Taylor, was one of the area's most successful attorneys. Their house was almost as big as ours, but their property wasn't as nice. Chase told me that his mother coveted ours.

"She wants whatever someone else has," he remarked with a frankness I hadn't expected. "So my father works harder and harder. He says it takes an ambitious woman to make a man a success. Are you ambitious, Summer?"

"I don't think I'm overly ambitious," I told him. "It's not good to be too ambitious. Mrs. Geary says, 'Men would be angels and angels would be gods.' It's a quote from some playwright."

He laughed.

"How lucky you are to have so wise a maid," he said. I didn't like the way he said maid and told him firmly that Mrs. Geary was more than a servant in our house. My flare of anger didn't frighten him.

He smiled at me and said when I got angry, my eyes were the most exciting jewels he had ever seen. I blushed and he kissed me. I thought, maybe Mrs. Geary was right after all about a young girl burdened with a woman's body. Feelings went off like alarms through my breasts and down into my thighs. We kissed again and again, each kiss longer and longer; when we touched our tongues on our most recent date, I had to scream at myself to stop him from pulling down the zipper on my Capri pants.

"Don't you want to?" he whispered in my ear. We had parked off the road to my house after going to the movies.

"Yes," I said, "and no."

"Teasing me?"

"Teasing myself," I said. "So let's stop before I break out in pimples."

He laughed.

"Who told you that would happen, Mrs. Geary?"

"No. I made it up," I said. My sense of humor kept him smiling even though I knew he was frustrated. I was too, but I'd die before confessing it.

If he asks me out again, I'll know he really cares for me. If not, I thought, I've been lucky. That was something Mommy taught me.

Maybe I wasn't such a little girl. Maybe turning sixteen was an understatement. Maybe I was old and wise for my age and all the things Mrs. Geary thought and feared about teenagers today simply didn't apply to me. Maybe I was too arrogant.

Maybes hovered everywhere, bouncing about me like the balloons tied to all the trees.

I ran down Mommy's ramp in front of the house and joined Daddy at the tables. The party was being organized like a camp event. All my guests had been encouraged to bring their bathing suits. Four years ago, Daddy had gotten Uncle Roy to construct a raft which they placed at the center of the lake. We had pedal boats and two kayaks as well as two rowboats. The lake had catfish and bass. However, Uncle Roy complained that fishing in it was like dipping your hook into a goldfish bowl. He said there was no challenge.

He was over by the dance floor making sure it was laid down properly. I looked about, expecting to see Harley, too, but he wasn't anywhere in sight.

"Hi, Uncle Roy," I called approaching. He turned from the floor where he was kneeling and looked up at me.

"Hey, Princess. Happy birthday." He had been calling me Princess for as long as I could remember. Once, when I walked in on a conversation Uncle Roy was having with Mommy, I heard him wistfully say, 'She could have been my daughter.' I had no idea what he had meant at the time, but I knew he meant me.

"Thank you, Uncle Roy."

"The way some of you kids dance these days, this thing could splinter up in minutes," he complained. "I told them I wanted thicker boards."

"It'll be fine, Uncle Roy," I assured him.

"Umm," he said skeptically and stood up.

When I was younger, Mommy often described how safe and secure she would feel when she walked in the streets of Washington, D.C., holding Uncle Roy's hand. It wasn't merely his size, his muscles, his large hands that surely swallowed hers in a gulp of fingers that gave her this security. Uncle Roy had an aura of power about him, a danger that came from his sleeping rages, I thought. Although no one could ever be as sweet and loving to me as he was -- with the exception of Mommy and Daddy, of course -- I always sensed the tension and blood-red anger lurking just below the surface of his every smile, his every word, his every glance and look.

Even Chase remarked to me one day that my uncle reminded him of a secret service agent or something.

"He looks at me like he expects I might try to assassinate you. He makes me nervous. Man, I wouldn't want to face him in some dark alley."

"He's a pussycat," I said even though I secretly agreed.

Mommy told me Uncle Roy was so hard and distrusting because of all the disappointments in his life.

I didn't really understand what was the biggest, not yet, but soon enough I would.

It would be another gift from time and age, the sort you wished remained wrapped and left under the Christmas tree forever and ever.

"Where's Harley?" I asked Uncle Roy.

He did what he always did whenever Harley's name was mentioned. He tightened his lips and lifted his shoulders as if he was preparing to receive a blow to his head.

"Thinking up some crime or misdemeanor," he replied.

"Uncle Roy," I said smiling.

"I don't know. He didn't come down to breakfast, which isn't unusual. That boy sleeps more than he's awake and especially sleeps late on weekends. Soon, he won't be able to; soon, he'll have to work for a living," he said with relish.

Uncle Roy was referring to the fact that Harley, if he passed his finals, would graduate high school this year. He attended the public school. Unfortunately, Harley had been in trouble at school most of his senior-high years. He had been suspended three times and almost expelled for fighting. He had been accused of vandalism and stealing, but that couldn't be proven.

Harley was far from being an unintelligent boy, and he was even far from being lazy, especially when he was doing something he liked. He had artistic abilities. He liked to draw, but mostly buildings and bridges. Mrs. Longo, his art teacher, wanted him to pursue a career in architecture, but Harley acted as if that was the same as telling him to pursue becoming a NASA astronaut.

Uncle Roy wanted him to enlist in the army, even though his own experience with it had been a failure. He had been court-martialed for going AWOL right after Mommy had fallen from the horse and become a paraplegic. He was in Germany at the time, and he wanted to come right home to her; but he had violated a leave once before and he was on probation. As a result he received a dishonorable discharge after serving some time in a military prison, which was something Harley threw back at him whenever they got into a bad shouting match.

It amazed me how fearless Harley could be whenever he had to face Uncle Roy. Harley was a slim, six-foot tall, dark-complexioned boy with hazel eyes spotted with green. He wasn't as handsome as Chase, but he had a certain look that reminded my girlfriends of Kevin Bacon, especially when he smiled with disdain or mockery, which he often did these days. He made fun of all the boys at Sweet William, even Chase, calling them and my girlfriends "mushy kids," because of their privileged lives, their money, their sports cars and clothes and what he termed their "fluffy thoughts."

He refused to categorize me the same way, however, claiming I was somehow different even though I came from a family with money and attended the same private school.

"Why am I different?" I asked him.

"You just are," he insisted.

"Why? I do everything they do, don't I? Few of them have more than I have."

"You just are," he repeated.

"Why?"

"Because I say so," he finally blurted and walked away from me.

He could be the most infuriating boy I knew, and yet...yet there were times when I caught him looking at me with different eyes, softer eyes, almost childlike and loving eyes.

It was all so confusing.

That was why I sometimes thought that Mrs. Geary might be right about my being too young for the jewels of womanhood I was blessed with.

I looked toward Uncle Roy's house. I was disappointed. I had hoped Harley would be almost as excited about my party as I was and would be out here by now.

"Maybe I'll go see if he's at breakfast," I said.

"Don't waste your time," Uncle Roy advised. "Hey!" he screamed at one of the workmen. "You're putting that in wrong. It's a tongue and groove."

He walked away and I started for his house. Uncle Roy had built a modest sized two-story home with a light gray siding and Wedgwood blue shutters. It had a good sized front porch because he said he had always wanted a house that had a porch on which he could put a rocking chair and watch the world go by. He got his wish, but there wasn't much world to watch go by here except for the birds, rabbits, deer and occasional fox. With any main highway a good distance away, there were no sounds of traffic either. A car horn was as distant as the honk of a goose going north in summer.

Uncle Roy claimed he had always hated city life anyway, and when he had lived in Washington, D.C., he had gotten so he could walk in the streets and shut out everything. He did look like a man who could pull down shades and curtains and turn his eyes inward to watch his own visions and dreams stream by.

Above their front door, Aunt Glenda had hung a bronze crucifix. Once a week, she brought out a stepladder and polished it. The front door was open, but the screen door was closed. I knocked softly on it and then called to her. I could hear her recording of gospel songs which was something she played while she worked in the kitchen or cleaned. She obviously didn't hear me, so I opened the door and stepped into the house.

There was always some redolent aroma of something she was cooking or baking. Today, I smelled the bacon she had made for breakfast. I called to her again and then looked into the small living room. She had turned it into a shrine to Latisha. There were pictures of her everywhere, on the mantel above the fireplace as well as on the tables and on the walls. Spaced between them were different religious items, pictures of saints, cathedrals, and icons of Christ. Usually, there were candles lit, although there were none lit this morning. The room itself had a dark decor, furniture made from cherry wood, oak and walnut with a wood floor and area rugs. Mommy and Daddy had bought them a beautiful grandfather clock as a house gift, but no one bothered to wind it and have it run.

"Every day now is the same as the one before it," I once heard Uncle Roy tell Daddy when Daddy had asked about the clock. "Especially for Glenda. Why bother with time?"

There was no one in the dining room so I went down the hallway to the kitchen. The music was playing on a small CD player, but Aunt Glenda was nowhere in sight. However, I saw through the pantry and back door that she was out hanging wash on a clothesline. She liked it better than a dryer because she said the clothing smelled sweeter from the scents of flowers in the air. As usual, she was wearing a faded housecoat and slippers. Her dark brown hair streaked with prematurely gray strands was down to her shoulders, and I could see from the way her mouth moved that she was either talking to herself or saying some prayer to her dead daughter.

I retreated to the stairway and listened for some sounds from above to indicate Harley was up. All I heard was the faint drip, drip of a bathroom faucet.

"Harley," I called. "Are you awake?"

"No," he immediately shouted back.

It made me smile.

"Talking in your sleep again?"

"Yes," he said. "Don't wake me up."

"It's late, Harley."

I started up the stairs. Harley and I hadn't grown up exactly like a brother and a sister, but we had spent so many of our young years together, I sometimes thought of him that way. Lately, if I suggested it, it seemed to bother him, so I stopped.

"Are you decent?" I called from the top of the stairway. There was just a short hallway to the right that passed his bedroom and what had been Latisha's nursery; there was an equally short hallway to the left that led to Uncle Roy and Aunt Glenda's bedroom and a bathroom across from that. The windows on both ends were small, and the wood paneling was dark. Even with the bright day, it looked like a tunnel.

"Am I decent? Depends who you ask," Harley replied.

I laughed and stepped up to his bedroom doorway. He was still in bed, lying on his stomach, the pillow over his head to block out the sunshine, the blanket down to his waist. I knew from other times that he liked to sleep in his underwear.

Harley's room was half the size of mine. He had a very nice dark maple-wood bed, matching dressers and a desk Uncle Roy had actually built himself that was set to the right of his two bedroom windows. There were papers scattered in a disorganized fashion over it, two books opened and face down and a small pile of notebooks beside that.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...