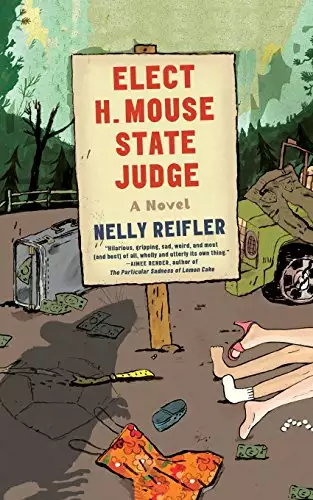

Elect H. Mouse State Judge

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A terrible crime occurs in Elect H. Mouse State Judge.

Two young girl are abducted and held hostage by a band of religious fanatics. The girls' anxious father, a politician on the eve of an important election, has reasons of his own not to go to the police, so he hires a pair of shady private eyes to investigate. All the elements of a classic noir—except that the kidnapped girls are mice, the abductors are Sunshine Family dolls, and the detectives are Barbie and Ken.

Part 1970s childhood dreamscape, part Raymond Chandler, this is a world both familiar and transformed. Sex shops, illicit affairs, spies, political hypocrisy, and dangerous zealots may coexist with Barbie and Ken's acrobatic poolside sex, but the crises of faith that Nelly Reifler's characters face are as real as our own. Elect H. Mouse State Judge is an unusual—and masterful—blend of irony and tenderness, and a moving portrayal of a father trying and failing to do the right thing.

Release date: August 6, 2013

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 112

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Elect H. Mouse State Judge

Nelly Reifler

1

H. Mouse was running for State Judge. He had diligently worked his way up the ranks from apprentice to secretary to uniformed guard to courtroom stenographer to lawyer to attorney to village councillor. And now the day had come for him to place the ballot box out on his porch and invite the citizens to vote for him. He'd taken a red box, emptied of its succulent raisins, and covered it in white paper. He'd cut a slot in the top, wide enough to easily slip in a folded ballot, but not so wide that ballots could be as easily slipped out. He'd weighted it down with gravel from his circular driveway so that the brisk autumn breeze would not pick it up and blow it away. And on the front he wrote in large print letters, ELECT H. MOUSE STATE JUDGE.

He hefted it off the mudroom floor and balanced it on his plump belly. Then he waddled outside to his porch. It certainly was a fine day, thought H. Mouse. Up and down his street sat handsome, symmetrical houses, all with upstairs and downstairs, with shutters and porches. All had real outlets with real electricity into which you could plug real lamps that really lit up. Each had a chiffonier that opened and closed, containing wineglasses, plates, and a roast turkey or a shiny ham decorated with brown crisscrosses. The houses had rugs and beds. Some had a coat rack, an umbrella, a framed Impressionist print; others a refrigerator, towels, a cradle. H. Mouse felt enriched thinking of the things in his neighbors' houses and his own. Times were good, he thought, neighbors were happy and prosperous and everybody was organized and clean and lived with the satisfaction of knowing true order. It would be a perfect moment for him to ascend to his newest role in his career as a public servant. It was the right time for his message.

He pulled up one of his real wood rocking chairs and awaited the voters' visits.

2

The Sunshine Family huddled in their green plastic van. They had round eyes, smooth chests, and short legs.

Mother Sunshine said, "It is time."

Father Sunshine said, "Now is the moment as has been ordained by destiny."

Mother Sunshine handed Father Sunshine the long-distance binoculars. Girl Sunshine and Boy Sunshine hopped up and down. The hinges of their knees and ankles squeaked. In unison they chanted, "Enlarge the family, enlarge the race. Widen the circle, tighten the brace."

"Hush, children. Father is plotting our next move." Mother Sunshine smoothed her calico apron down with her curved fingers. The children dropped to the floor, sounding twin thuds with their hard behinds.

It had been a long encampment here in the forest on the edge of town. When you are on a mission for something greater than yourself, you are willing to wait for the opportunity to take action. The van was parked in a circle of trees a quarter mile off the old dirt fire trail. For many moons Mother Sunshine had been cooking the family's meals of rice gruel and poached varmints over an open fire. The children had been memorizing the words of the Book of Doctrines, and repeating its hieratic ordinations to each other. And Father Sunshine had been calculating, communicating in the Old Language, through whispers, with the Power, waiting for a sign.

"He has moved to the porch," said Father Sunshine, adjusting the focus on the binoculars. "He has carried the ballot box out there with him. I see he has pulled up a real wood rocking chair. Now he is sitting down."

"And the others?" asked Mother Sunshine.

"Readying themselves for their new life, although they are not yet conscious of this truth."

3

Susie Mouse handed Margo Mouse a rag doll. "Pretend you're the teacher now," said Susie. "I'll be the bad student who gets punished, and this is the principal. Send me to the principal's office."

Margo said nothing.

"Margo!"

Margo turned her head slowly. "What?"

"Stop staring out the window. Be the teacher."

Margo's white eyelet dress was wrinkled and her barrette was dangling off her ear. She turned her head back toward the window.

"You're hopeless," said Susie. "You're a loser."

"There's something out there," said Margo.

"There is not. I've told you already. It's the same stupid elm and the same dumb old swing set, and the shed and the fence. That's what's out there."

"Something's watching." Margo pointed. Susie followed with her eyes and squinted. The attic playroom had a view of the village, with its shops and roundabout and benches. Beyond that, the sisters could see the sparse edge of town, where the few houses were surrounded by acres of fields, and where the service road was dotted with the occasional gas station, strip mall, or diner. The dark, wild forest rose up in the distance. The trees formed a mass that looked solid, impenetrable. It was hard to believe that there was earth under those trees, that there were living creatures in the fortress of those hills.

"How could anything be watching from that far away?" said Susie. "You're just all stressed out because it's Election Day. You worry about Dad too much."

"I don't know." Margo shook her head. "It's not about the election. I'm afraid."

"Don't be ridiculous."

But Margo noticed that Susie's voice sounded a little less shrill, and that the words came out a little more slowly.

"Forget it," said Margo. "What were we playing?"

4

"Wait here," said Father Sunshine, making the sign of the Dodecahedron over each of his children's heads. Girl Sunshine and Boy Sunshine sat on their piece of foam rubber in the corner. Their legs jutted out in front of them. They stared straight ahead.

"It is windy today," said Mother Sunshine. The tin cans dangling from a clothesline, set up to repel bears, clanked against each other tunelessly.

"If the Power fells me with an enloosened branch, so it is to be," said Father Sunshine. "Do not mourn for me; I will have joined the Twelve Hundred Celestial Angeldemons. If the Power fells me, you must carry on the Project."

"I shall," said Mother Sunshine.

Father Sunshine bent his hip hinges, pulled on some pants, slung his backpack over his shoulders, and strapped his pistol into his belt.

5

H. Mouse thought about the things he would do as State Judge. He would decide who gets what. And whether this one or that one goes to jail or goes free. He'd talk to the citizens about fines and rewards. He'd pick juries and teach them all about the law. He couldn't remember a time in his life when doing good and furthering the cause of fairness were not the twin beating hearts of his being. Rocking on his porch, he thought of the word parity, and about how he believed that each of us is basically good, equally so—no matter how some may stray because of their stressful circumstances. If everybody could be given the proper tools for moral strength and ethical decision-making, theft would end. And abuse. And dishonesty.

After all, he told himself, when pushed into a corner or backed to the edge of a precipice, the best of us might find ourselves doing things of which we never imagined we were capable.

A picture flickered through his mind like a bat, but he shooed it away. His stomach squeezed and he suddenly tasted acid in his mouth. Was he hungry? He patted his belly and looked at the sky. It was close to noon, and he was indeed feeling rather munchy. He could picture the tray of muffins baked by his daughter Margo that morning, sitting out on the counter, where she had set them to cool.

But what was this coming down the street? Why, it was Fernanda Gekko, with a folded piece of paper. She seemed to be, as usual, dressed to the nines, with a flowing skirt, long gloves, satin bonnet, and alligator purse. H. Mouse pushed himself up from the real wood rocking chair and brushed his vest in case of stray dandruff. He buttoned the vest button that always popped open when he sat. He waved at Fernanda as she approached his porch.

"Ms. Gekko, how delightful to see you."

"H.," she said, daintily gathering the cloth of her skirt to ascend the porch steps. Lace-up boots of aubergine leather peeked from her petticoat. "It's my pleasure to cast a ballot in your ballot box today."

"I cannot thank you enough for your support." He gave a slight bow.

"You're the candidate for me." Her eyes seemed to grow a little wetter as she added, "You're one of the few good ones out there, H."

He smiled at her. He didn't know what had happened in her past, but he wanted to reassure her. "Ms. Gekko, we are all good, each and every one of us. Some are just weak, but none are hopeless."

"That's an extremely charitable point of view," she said. "Another reason I'm doing this." And with that, she dropped the folded paper through the slot of H. Mouse's box.

"Well, thank you again. Thanks for coming by."

Fernanda Gekko patted his sleeve and sighed as she turned and descended the steps. He watched her walk away, down the street toward the center of the village. There was nothing wrong with looking.

6

As their father chatted on the porch, Susie and Margo were being dragged away from their home in a sack. Father Sunshine had been conversing with the Power for many rotations of the earth, offering his loyalty. In exchange, the Power had bestowed upon Father Sunshine the lessons needed to focus his pyramidal tract, the section of the brain that was implanted by the Ancients in order to channel their energy from generation to generation. This energy endowed Father Sunshine with the Strength of the Dozen. Even though his captives wriggled a little in the bag, they were silent (he had gagged them with wadded cloth and tape) and relatively still (he had trussed them with Manila rope).

Without the sisters' knowledge, the Power had guided them out of their high playroom and into the kitchen, where they had been standing when Father Sunshine reached the house. He had peeked through the window: they were leaning against the counter, eating some kind of baked good and laughing. He forgave them for taking pleasure in the corporeal decadence of sugar and leavening. They did not know yet, that was all. He would have to grab them both at once.

He had opened the screen door, pistol in his hand.

The littler one had seen him first. She'd opened her mouth, gasping, showing him its white, wet contents.

He whispered to them, "Do not make a sound, or the Power will shoot this gun and kill your bodies. You are lucky. You are part of the Universal Plan. You have been picked for the Ascendant Widening of the Circle." He jabbed the gun in the air, pointing it alternately at the stomach of one and then the other. "The Power will not harm your bodies if you stand still now." They had stood still. That was when he had pulled the tape, cloth, and rope from his belt.

Did he question the Power for even a second? Did he ask why the Power had sent him these two, with their beady black eyes and plump little vessel bodies that only reached as high as his hip hinges? Of course he did not.

Now he reached the fence at the rear of the adjacent property. He had clipped it a month ago, and the loosened portion toppled easily. Turning left from there it was a straight shot through one more yard, then up an alley behind the water-treatment station to the mouth of the winding forest road. He knew he would have to carry them, not just tow them, once he hit pavement. At the base of the forest road he would pick up the old all-terrain vehicle he had hidden behind a shed, stuff the sisters in the sidecar, and ride to the fire trail. There was a second unused shed there, where he could once again stow the vehicle. Mother, Boy, and Girl Sunshine would be waiting at the fire trail. He figured that at that point, they wouldn't need the sack anymore. Everyone could walk back to the van together.

7

Susie and Margo both went utterly limp inside the sack. It was dark, and the uneven ground moving under their bodies bumped and bruised them. Susie concentrated on breathing; she felt as if she might forget to breathe and then die. Margo was shocked by how real it all felt, how it was happening now, at this very moment—but on the other hand, she wasn't surprised at all. She had known something was coming. She had known it was going to get them.

Each sister kept her body close to the other, to the extent that it was possible.

8

Where were they?

H. Mouse stumbled on a rag doll that lay, arms and legs splayed haphazardly, directly on the threshold between the kitchen and the mudroom.

He called their names.

Nothing. This wasn't like his daughters. Gripping the banister, he waddled up the stairs to their bedroom. Neatly made twin captain's beds, more dolls, the grasshopper in its cage, running round and round on its grasshopper wheel. At the base of the attic steps he called again: "Susie! Margo!"

Maybe they were playing a game, he thought. They were good and sweet. They weren't prone to practical jokes. But it was true that Susie was reaching the age where she'd begun to form an identity outside the family unit; could she have roped Margo into some harebrained scheme to worry H. sick? He pulled himself up the attic steps. He imagined his daughters hiding in a corner under the eaves, whispering to each other in that secret language of theirs—Obby, they called it. He imagined them covering their mouths and trying to stay quiet as they heard him approaching. He imagined them jumping out and shouting "Boo!" at him and then collapsing in giggles. But the attic was dim and empty. He stepped over another doll that was sitting at a shoe-box desk. There was a low shelf holding picture books pressed under the slanted ceiling, and behind it a triangular cavity. He grunted a little as he heaved the shelf out from its spot. Nothing back there but shadows.

His heart pounded. Maybe they'd gone over to visit one of the neighbors. But as he had the thought, he understood that he'd only had it because it's one of the things you're supposed to think when your children suddenly go missing. Even so, he made his way back down to the kitchen, where he picked up the receiver of the wall phone.

"Operator."

"Give me ELdridge 3-7717," said H. Mouse.

After a couple of rings Sally Gerbil picked up. "Hello?" came her creaky voice.

"Sally, it's H."

"Oh, yes, H. Thank you for the call. I nearly forgot it was Election Day. I'll toddle over to cast my ballot after tea and crumpets."

Election Day! H. stretched the phone cord as far as it would go and peered out the dining-room windows at the porch. The ballot box was still there.

"Sally, you haven't seen Margo and Susie today, have you?"

"The little ones? Nope. Haven't seen 'em."

Next he called Binne Volesdöttir, on the other side, who said in her thick accent that she hadn't seen them either. Nor had Pinkney Plastic-Hat across the street.

He found himself slouched on the kitchen floor, head hanging, legs bunched up against his chest. From this vantage point, the crumbs and dried, moldy vegetable scraps around the edge of the linoleum looked like miniature, multicolor snowdrifts. An ant climbed one of the drifts and selected a morsel, wiggling its antennae. H. had always thought he had a clean kitchen; he hadn't realized it housed a tiny world of dirt and decay. When he raised his eyes a little bit, though, he noticed that some of the crumbs were in the middle of the floor, and they seemed to have fallen in a line—all the way to the back door off the mudroom. He crawled over to one cluster of crumbs, picked some, and sniffed them. They were soft and fresh: bits of Margo's blueberry muffins—the mostly full tray of which still sat on the counter.

He took a deep breath. It was sinking in. He had no idea where his daughters were. He reached for the edge of the counter and pulled himself back up to standing. He grew dizzy for a moment while the blood rushed out of his head. He took a couple of deep breaths, then returned to the phone to ring the direct number for Bub Flytrap, the police commissioner. H. had known Bub ever since they'd been apprentices together, double-dating and playing pickup mumblety-peg in the park. Oh, those were the days!

"Operator."

"Give me—" H. started. Then he stopped, his voice catching in his throat. "Never mind."

H. hung up the phone and sank back down to the kitchen floor.

9

Margo and Susie found themselves standing in a scrubby clearing in the woods. They were sore all over. They'd been piled, still inside the sack, on some vibrating machine, noisy and smelly.

Now they were unbound. Their limbs were weak from the trauma, and the ropes had cut off their circulation, leaving their extremities numb. Margo looked down at one of her legs and saw that it was badly scraped and bleeding. She tried to bend down to brush the dirt out of her wound, but she was too unsteady on her feet and fell over. Their captor took a few stiff steps toward her and offered his hard, shiny hand to help her up.

"The others will be here soon," he said.

Susie started to cry again, drooling around the wad of cloth in her mouth. Margo, with great effort, reached over and touched her sister. Susie always cried first, and often the moments when Susie cried—scary movies, thunderstorms—were the same moments that Margo felt like she was separating from her body and hovering at a slight distance, watching.

A minute later, three figures came clomping toward them over the brush. They moved choppily, with legs that stuck out in front of them and hinged arms that clicked back and forth. One had yellow hair and a long dress with an apron. The other two, who were smaller, had darker hair and wore green outfits with silver emblems on them. Their skin was uniformly pink and shiny. Their eyes were blue spheres with big black pupils.

They stopped before Margo and Susie. The one in the dress bent at her hips and clicked her arms out, pulling first Margo, then Susie, close. Margo smelled smoke and mildew and plastic.

"Welcome, our dear new Spirit Carriers. I am Mother Sunshine. I know this is all very surprising to you now, but soon you will begin receiving the Ancient Teachings as are laid out in the Book of Doctrines. You are extremely special. You have been chosen to help fulfill the prophecies."

The male captor spoke. "Whatever you think your names are, they are no longer of use to you. From now on you are Vessel Alpha and Vessel Omega."

The smaller figures stepped forward now. One said, "I am Boy Sunshine."

The other said, "I am Girl Sunshine."

In unison they chanted, "Welcome, sisters. Join us in the Dodecahedron."

Margo and Susie noticed then that the smaller figures had stepped into the middle of a circle—well, not exactly a circle—delineated on the ground by small rocks that glittered with mica. The one who called herself Mother Sunshine gave Margo and Susie little pushes, and they stumbled into the space. Mother Sunshine smiled ecstatically. Father Sunshine marched over and stuck his arm into the glittering space. Margo felt his cold hand hanging over her head. She moved her eyes and saw that Susie was trembling. Father Sunshine muttered something Margo couldn't understand.

And then Margo and Susie were led, slowly and gently, along the path into the depths of the woods.

10

It was late afternoon now. A steady stream of voters had been casting their ballots for hours. H. Mouse felt as if he were performing a dreadful pantomime, waving, greeting them, thanking them, giving the little bow that was one of his trademark gestures.

There was still no sign of Margo and Susie. But H. had realized it with utter clarity in that moment at the telephone: he couldn't go to the town police for help. Not on—or anytime near—Election Day. He knew better than anyone how local justice worked: even if he were the one to report his daughters missing, the authorities would be required to rule him out as a suspect. Standard procedure—in fact, one of H.'s own cases back when he was an attorney (Citizens v. Fawn Doe) had set the precedent for it. If he made a fuss and asked for special treatment, it would undercut his campaign's primary message of fairness and equal treatment for all. But if he let them begin digging around in his past—well, no, he just couldn't let that happen. No more than he could have them dig around in his present. He'd come all this way without anybody poking their snouts where he didn't want their snouts.

Now he sat in the darkened den, holding a strong cordial. He reassured himself. Again. Whatever may or may not have happened behind the scenes had nothing to do with his ability to serve in public office. He was a good servant of the citizens; their lives were his charge, and he took his duties as seriously as a priest.

He sighed and put down his empty glass. Standing, he buttoned his vest and pulled his car key out of his pocket.

There was only one place he could go for help.

11

Barbie and Ken were fucking. They were fucking and screwing and doing it. They did it like bunnies and dogs and horses. Poolside, they humped, slamming against each other, grinding, wedging their legs into each other's crotches. Skipper watched on in her plaid jumper, bored.

"Unh, unh, unh," said Ken.

"Ah, ah, ah," said Barbie.

Skipper bent her leg daintily at the knee. "Don't you guys have a job to do or something?"

The truth was, they had just finished a job, and that was what made them so horny. They always got like this after they were paid.

Barbie popped off her head, and Ken stuck his hand inside the cavity where her neckball had been.

"Oooh, yeah," said Barbie.

"Oh, baby, it feels so good to be inside you," said Ken. "Do you like this? When I move it like this?"

"Yes," she said. "Oh, yes, I do."

Ken grasped Barbie's head and lifted his right leg up. He stuck his foot inside her head. Barbie moaned. The whole orange inflatable deck shook as Ken rocked in and out.

Skipper took out a pink nail file and ran it along her fingertips. She looked out at the view. From where she sat on a clear blow-up chair, she could see the whole valley: the cute little town below, with its uniform houses where regular folk lived, its roundabout, its market center, the murky mountains beyond. The sun was setting behind the mountains. Here in the southern hills it was always warm and dry, and that was nice, but every so often she wished to know what it was like in the cool valley or up on the foggy mountains. Lazily, she directed her gaze back across the deck.

Ken, his foot still inside Barbie's head, removed his own head and passed it to Barbie. Barbie gripped it and rubbed the brown hair across her chestbumps in circular motions.

"Now." Ken's mouth spoke. "C'mon, baby. Give it to me now."

Barbie lifted Ken's head, and lowered it—teasingly slow—onto her own neckball. She rolled his head around on the pink orb that topped her long, slender neck. Ken withdrew his foot and put Barbie's head on his neckball. Then they slammed their bodies together once again.

"Unh, unh, unh," said Ken.

"Ah, ah, ah," said Barbie.

The wavelike motions were starting to get to Skipper. She stood up and made her way delicately across the deck, down the gleaming white stone walkway, to the threshold of the pink townhouse. Her pink twirling baton was leaning against the door. She picked it up and twirled it a couple of times. Inside, she rode the elevator to her room on the second floor.

12

How he hated to do it. H. Mouse got out of his brown sedan at a turnaround on Floralinda Drive, a good distance from his destination. God forbid anyone see his car parked at the place itself. It was hot over here, even in the evening; succulents lined the byway, and sandy soil drifted onto the edges of Floralinda Drive's shiny tar surface.

He'd made this trip twice before: the first time was after he'd stupidly agreed to join a poker game, thinking it would be a nice way of connecting with the community; he'd wound up with some debt he needed to tuck away. The second time, well, that was worse. He'd let his urges get away with him, and someone needed to be encouraged, discreetly, firmly, to leave town.

He trudged along the side of the road by the light of the occasional zinc streetlamp, stepping on ice plants and tiny aloes. Sweat poured down his face, and he mopped it off with a real cloth handkerchief. His tummy churned and he tried his best to push away the old images that fluttered around the eaves of his mind on bats' wings. He had forgotten lunch. He felt faint.

He paused at the bottom of the long, curving driveway and gazed up the hill. Palm trees arched over it, and parrots darted among their fronds, backlit by the sapphire late-dusk sky. He took off his vest, rolled up his sleeves, and unbuttoned the top two buttons of his shirt. Even in his state of panic and anxiety, H. couldn't help but notice the smells of desert herbs—rosemary and sage—floating in the gentle breeze.

The townhouse rose, magnificent, sparkling, on the hill. As H. approached, the pool came into view, and he could see that it was wobbling furiously.

He knew what to expect, and braced himself. He crossed the lawn, avoiding the sprinklers, and climbed the steps. The pool was illuminated by floodlights.

There they were, coupling as usual. Their long, lean, peach-colored bodies were contorting in jerky, synchronized motions. They moaned and gasped and grunted.

He sat down in one of the blow-up chairs and watched, oddly calmed by the sight of their calisthenics. There was a half-full glass of iced tea in the chair's cup holder; he drank it. It was sweet and slightly astringent.

When Barbie and Ken finally finished, and he saw that they had their own heads back on their neckballs, he cleared his throat.

Barbie spoke first: "Why, H. Mouse! What a surprise to see you here tonight."

"Yeah," said Ken, sitting in the other chair and pulling Barbie down onto his lap so she covered his groinlump. "Isn't it Election Day?"

"Please," said H. "I'm really having an emergency here. I can't even express to you how dire this situation is. They're my life, my whole life…" He had told himself he wouldn't break down, but here he was, blubbering right in front of these, these … sleazy operators.

Barbie lit a cigarette and leaned in toward H. She stroked his sleeve with her free hand. "Hey now," she said in her twinkling voice. "Hey."

"H.," said Ken, taking a drag from Barbie's cigarette and then sticking it back between her pink lips. "My friend, H. We're here to help. We're at your service. What can we do you for?"

"It's Margo and Susie," murmured H., wiping his nose on his sweat-soaked sleeve. "My daughters. They're gone. One minute they were home, the next minute they were nowhere." He sobbed again. "Margo made blueberry muffins this morning." And as he said it, he felt a kind of vertigo. Had it really just been this morning that he'd passed by the kitchen doorway and seen his daughter standing on the little real wooden stool and measuring some flour out into a real sifter with parts that really move? "Just this morning."

"Wait a minute," said Barbie. "What do you mean they're gone."

"They disappeared. I think they were taken out the back door." H. took a deep breath. Collect yourself, he thought. "Okay, it's probably nothing. I'm probably overreacting. I called around to the neighbors. No one saw anything. I didn't want to go further than that because, yes, it's Election Day. You know what that means, I presume?"

"Sure, sure," said Ken. "We get your drift. You're an upstanding citizen, a good leader. Scrutiny doesn't play well, even if you're the victim. And what if it's a false alarm? Why make a fuss?"

"And besides," said Barbie—did H. detect a slight twist in her tone?—"scrutiny of one kind can bring scrutiny of another. You wouldn't want that."

H. didn't have to be reminded that Barbie and Ken could ruin him. "No," he said evenly. "I wouldn't want that."

"What I think you're getting at," said Ken, "is that you need our help finding the kiddos. Am I right?"

"Yes," said H.

Barbie leaned forward. "Okay, let's assume they've been taken. Was there a ransom note?"

H. shook his head.

"And…" Barbie let a puff of cigarette smoke curl slowly from between her lips. "Do you think there's any chance this is an act of revenge?"

"Revenge?" H. tried to look shocked. Barbie tilted her head and fixed him with a cool, steady gaze. H. sighed. "Oh. No. I mean, I don't think so." A pulse of dizziness overtook him, and he flopped back on the inflatable plastic, eyes squeezed shut.

"Oh, H.," said Barbie, soft once again. He opened his eyes. She rose off Ken's lap. Then she cupped H.'s sweaty face in her elegant fingers. "Don't worry. We'll do everything we can to reunite you with your precious ones."

"For a price," said H.

"For a price," said Barbie.

Copyright © 2013 by Nelly Reifler

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...