Lynesse

NOBODY CLIMBED THE MOUNTAIN beyond the war-shrine. The high passes led nowhere and the footing was treacherous. An age ago this whole side of the mountain had flaked away in great shelves, and legend said a particularly hubristic city was buried beneath the debris of millennia, punished by forgotten powers for forgotten crimes. What was left was a single path zigzagging up to the high reaches through land unfit for even the most agile of grazers, and killing snow in the cold seasons. And these were not the only reasons no one climbed there.

Lynesse Fourth Daughter was excluded from that “no one.” When she was a child, the grand procession of her mother’s court had made its once-a-decade pilgrimage to the war-shrine, to remember the victories of her ancestors. The battles themselves had been fought far away, but there was a reason the shrine stood in that mountain’s foothills. This was where the royal line had gone in desperate times, to find desperate help. And young Lyn had known thosestories better than most, and had made a game attempt at scaling the mountain which myths and her family histories made so much of. And the retainers had chased after her as soon as people noticed she was gone, and they’d had cerkitts sniff her trail halfway up the ancient landslip before they caught up with her. That had been more trouble than she’d got into in any five other years combined. Her mother’s vizier raged and denounced her, and she’d been exhibited before the whole court, ambassadors and servants and the lot, made to stand still as stones in a penitence dress and a picture hung about her neck illustrating what she’d done. Her mother’s majordomo, still smarting from when she’d stolen his wig, had overseen her humiliation. And her sisters had mocked her and rolled their eyes and told one another, in her hearing, that she was an embarrassment to her noble line and what could be done with such a turbulent brat?

And her mother, in whose name all those functionaries had hauled her back for public punishment, had just watched, and Lynesse Fourth Daughter had looked into her eyes and seen . . . not even anger but sheer exasperation. Lynesse, a child with three Storm-seasons behind her and one more to go at least before anyone might consider her grown, had done a thing nobody else cared or dared to do. Disobedient, yes; irresponsible, yes; more than that, her mother’s look said, I cannot understand what would even kindle such a thought in your head. As though Lynesse was not badly behaved but actually sick with something.

That had been two Storm-seasons past. The sting of it had faded; the memory of that ascent had not. Which means it was worth it, the now-grown Lynesse Fourth Daughter decided.

They had only caught her that time because she had stopped climbing. She had only stopped climbing because she’d finally seen of what was up there: the Elder Tower. She had been the first human being to lay eyes on it for a very long time.

It hadn’t looked like the pictures. In the tapestries and the books, they drew it like a regular tower of brick, with windows and a door and a pointed roof, just there amongst the mountains. Some artists had even placed it on the very peak, and sometimes drawn it bigger than the actual mountain in that way they did. They drew queens the same way, with the lesser folk only coming up to their knees. Lyn had been quite old before she had even questioned the practice, so widespread was it. That had been when an artist seeking patronage had illustrated a family history, ending with a picture supposedly of Lyn’s mother and offspring, a little sequence of diminishing, facially identical figures. Lyn had complained bitterly that she was already taller than Issilesse Third Daughter, and been told, That is not the way pictures are made. She was smaller, under the artist’s hand, because she was less important. Fourth is less than Third.

She had given their tutor ulcers for half a short-season after that, insisting that four was smaller than three when made to do her sums.

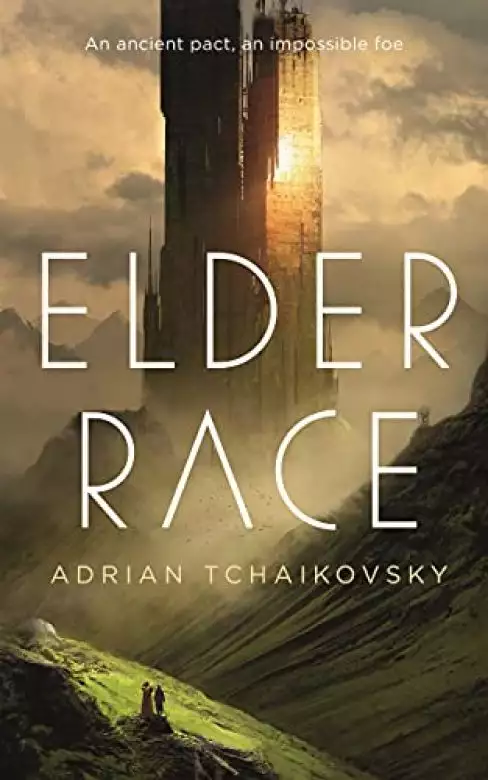

The Tower of Nyrgoth Elder, last of the ancients, was built into the mountainside. It had no sign of join or masonry. Some grand magic had just excised a great deal of the stone until all that was left was the tower, jutting from the new line of the mountainside, overhanging a chasm, reaching for the sky. The day had been crystal clear when she’d gone on her unauthorised jaunt all those seasons before, and she had good eyes. The image had stayed with her ever since.

Now she was looking on it again. Quite possibly she was standing just where her younger self had halted, though her memory didn’t quite preserve that much. It was evening rather than yesteryear’s bright midday, but the skies remained clear. According to the few communities that lived in the foothills, the skies over the mountain were often clear even when rain came in from the sea to trouble everywhere else. If you were the greatest sorcerer in the world then you probably got to say whether or not you got rained on, she decided. Assuming Nyrgoth still dwelled in his tower, as the legends said. He was very old, after all; he had been very old a long time ago. Even if he had not died, why should he not have travelled to some other land, or some netherworld that only wizards could access, or some other fate, bespoke to the magical, that Lynesse Fourth Daughter could not even imagine?

“You’re just going to stand there, then?” her companion asked. “It’s me making camp again, is it?”

Lyn was aware that, yes, it was entirely her right to demand that Esha do all the camping and cooking and the rest of it, because Lyn was royalty and Esha was not. Simultaneously she had only secured Esha Free Mark’s help on this journey by explicitly promising she wouldn’t act the pampered ass.

“I’m sure it’s my turn,” she said vaguely, eyes still upwards. “Do you think he’s watching us?”

Esha squinted balefully up towards the tower, but her eyes were bad at that kind of distance. The tower was just like a little toy to Lyn; likely Esha couldn’t make it out at all.

“He hasn’t magicked us up to his front door yet,” she pointed out. “Disrespect to the princess of the blood, if you ask me. Disrespect to my aching feet, too.”

“The road to the Tower of Nyrgoth Elder is long and hard because he decreed it so,” Lyn recited. “That it not be trodden lightly by fools, but only by earnest heroes when the kingdom is threatened by dire sorcery.”

“I would have magicked up a bell, or something, and I’d just turn up out of nowhere when it was rung,” Esha pointed out. “That way nobody would have to do all this uphill nonsense.”

Esha was of the Coast-people, who fell outside Lannesite’s strict reach, and maintained a tenuous independence along the sea’s edge and the banks of rivers and lakes. An independence bought with cartloads of fish and defended by the general difficulty of the terrain; hard to subjugate a people who could just go into the water at a moment’s notice, and then come out of it with spears and poison darts when you least wanted them to. Her skin was pale like most of her people, greenish white and heavily freckled with blue about the bridge of her nose and cheekbones. She had a hard, square chin and her straw-coloured hair had obviously been trimmed with the aid of a bowl. She was shorter than Lyn, compact of frame, wearing a wayfarer’s layers of wax-cloth and weft, with a cuirass of hard scales over it all in case of trouble.

Esha was a traveller, for all her complaints about the “uphill nonsense.” She was two full Storm-seasons Lyn’s senior without actually seeming much older. Lyn remembered her turning up at court at random intervals with her travellers’ tales and outlandish souvenirs, and only later worked out that much of Esha Free Mark’s journeying had been clandestine errands for the throne. That hard-won suffix attached to her name was the Crown’s guarantee of her right to go where she wanted without exception, and there were precious few foreigners who’d earned it.

Except, as Lyn grew up, the political landscape of Lannesite had grown more intricate, locked into a series of treaties with neighbouring states and non-states, so that Esha Free Mark’s anarchistic style of impromptu diplomacy had become a little embarrassing for the throne, and she had been called on less and less. One day, so said Lyn’s sisters, Esha would go pick a fight with someone, cross a border somewhere, and the writ of Lannesite would not bail her out.

When Lynesse Fourth Daughter had come asking for her help with a journey where nobody went and, after, to where nobody was currently returning from, Esha had jumped at the chance.

“I think,” she told Esha now, “that it is a good thing Nyrgoth Elder did not give my family a bell to ring, to summon him.”

“That so?”

“I think,” Lyn went on, “that if such a bell existed, I’d have rung it with all my might before my third season just to see what happened.”

* * *

The next morning they decamped with the dawn, ascending a mountain pass that seemed devoid of life, no song of beast, no chirr of creeping thing. The clear sky above shifted imperceptibly from beautiful to ominous, and Lynesse felt that there was some sound, too low or high for her to hear, that was nonetheless plucking at her innards, creating brief blooms of anxiety and fret that made her want to turn around and go back down. Glancing at Esha, she saw the same worry on her companion’s face.

“The Elder doesn’t much want visitors, does he?” the Free Mark said. “Doubtless he is considering some matters of philosophy and does not wish to be disturbed, by man or beast. What makes you think he’ll even open his door, let alone help?”

“The ancient compact still stands,” was Lyn’s only answer to that. She was aware that Esha probably thought it was more myth than matter, but she had grown up on the stories; they were a part of her as much as her bones and sinew. And if not now, then when?

And soon enough, through the silent, vacant land, they had come to the tower’s door, which was round and had no furnishing, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved