- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

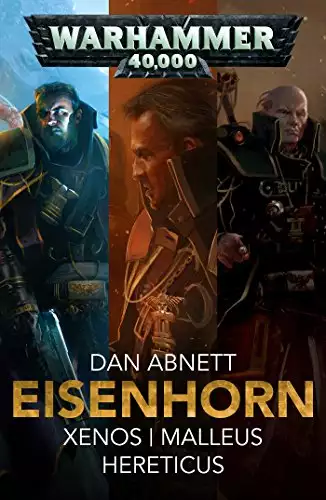

Discover one of the most well known Black Library characters, Gregor Eisenhorn, in this great value omnibus.

In the grim far future, the Inquisition moves amongst mankind like an avenging shadow, striking down daemons, aliens and heretics with uncompromising ruthlessness. Written by Gaunt’s Ghosts creator, Dan Abnett, this volume charts the career of Inquisitor Gregor Eisenhorn as he changes from being a zealous upholder of the truth to collaborating with the very powers he once swore to destroy. Part detective story, part interplanetary Epic, this omnibus brings together the novels Xenos, Malleus, Hereticus and The Magos, as well as four short stories.

Release date: November 15, 2016

Publisher: Games Workshop

Print pages: 944

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Eisenhorn: The Omnibus

Dan Abnett

I crossed over into Jared County via the pass at Kulbrech. Air links were down, because of the Cackle, so a reluctant motorised unit of the local militia conveyed me from the capital as far as Kulbrech Town, and then only because the Jared Commissioner had been so insistent. This was – oh – 223.M41, and I was only just out on my own.

Even then, at the very dawn of my career, I was treated with a mixture of fear and suspicion. The rosette, or the title ‘inquisitor’, or a combination of both, fairly focused the minds of those who met me. This attitude bores me these days. Back then, it gave me a sort of vulgar sensation of power.

Inquisitor Flammel had been killed six months before in a miserable warp transit accident, and I had been posted as a locum to cover his circuit, which was the fief worlds of the Grand Banks in the coreward reaches of the Helican sub. Circuit work is a drudge, and one acts, in the main, as an itinerant magistrate, travelling from planetary capital to planetary capital, reviewing flotsam cases gathered by the local authorities. Most are trivial and hardly Ordo business, scares conjured up by superstition and petty disputation, though I had spent eight weeks on New Bylar working through a caseload that eventually exposed a traffic in low-grade, unsanctioned psykers.

From New Bylar, I went to Ignix, the smallest and most peripheral of the fief colonies, a place locally regarded as the back end of all creation.

Ignix did not disappoint. Small, wet and whorled with ravines and meandering trenches created by an eternity of rainfall eroding its way down into the frothing seas, the planet is administratively divided into counties, each one millions of square kilometres.

Its capital is called Foothold, for it was there the first settlers made planetfall. They were miners, mineral extraction being the only profitable occupation a man can find on Ignix. Not long into their habitation, the miners of Ignix specialised and became wet miners, panning and sifting the planet’s thousand thousand fast waterways, many of them temporary run-offs that surge one day and are gone the next, for precious ores.

Wet mining fortunes had built Foothold into a decent-sized but drab town. All the worthwhile minerals had been shipped off-world in return for hard cash, and the place had been constructed from the residue. The buildings were stained and grim, many of them fabricated from locally cast rockcrete or a type of melta-formed pumice brick. I was put up in an airless residentiary, and went to the courthouse every day to review the pending cases. None of them deserved my attention, or even the rubber stamp of the Ordos.

I had been there four days when the Cackle began. The name is a local one, a more appropriate description would be seasonal electrocorporeal storms. A by-product of Ignix’s orbital variations and the virile behaviour of the star it circles, the storms visit each yearly cycle and blanket the northern hemisphere with a steady, florid electromagnetic display. The sky lights up. Corposant nests on rooftops and masts. Vox-links suffer. There is a continuous sound in the air, like a dry, evil chuckle, hence the name.

Some years it’s mild, others it’s bad. 223 was a bad year.

The Cackle was so fierce, it prevented any and all passage by air, including shuttle links from the lift harbour to starships at high anchor. Transfers on and off Ignix were suspended, and I was stuck for the duration, which turned out to be three weeks.

There was some novelty to be enjoyed at first. The flickering lights in the sky, day and night, were quite sublime, and produced certain hues that I swear I have never encountered since.

But the constant dirty chuckle became onerous and tormenting, as did the rancid, metallic sweat the charged air drew out of me. It was fuggy and close, and I quickly wearied of getting shocks from every damn metallic object I touched or used. I came to realise why the late Flammel had made Ignix a low priority on his circuit.

With the cases done with, there was little to do but wait for the Cackle to subside. I read, and studied, and struck up passing friendships with several similarly stranded travellers living in the residentiary, merchants mostly. Perhaps friendships is too strong a word: I knew them well enough to share a drink or a conversation or a game of regicide with, but nothing more. They understood what I was, and it made them nervous around me. For the first time in my career, that vulgar sensation of power began to feel like a burden.

Towards the end of the first week of enforced occupation, a message arrived from the commissioner of Jared County. Due to the vox-out, it was brought by a biker who had run the flooding levees and wash plains of the county limits overnight. I can only assume the commissioner had paid the man well, for he was in a poor state by the time he arrived. The Foothold administrator, an old fellow called Wagneer, brought the message slip to me and waited while I read it.

‘He seems most insistent, this commissioner,’ I remarked.

‘Mal Zelwyn? He’s a good sort, very dutiful. He knew you were in town on circuit duties, and evidently hopes you might oblige him.’

I held the slip up.

‘Do you think this is genuine, administrator?’ I asked.

Wagneer shrugged his sloping shoulders. ‘Sounds like a hot one to me, but what do I know? I don’t have rosette training.’

Zelwyn, the commissioner of Jared County, had reported a pair of killings in his township, the unimaginatively named Jared County Town. He suspected cult activity, and requested an assessment by the circuit inquisitor. I would have dismissed it except for two facts. One, I had nothing better to do, and two, Zelwyn had written:

The victims suffered deep, random cuts and slashes to the body, having been slain by a crushing head wound. Each victim was missing its left ear.

‘How do I get there? Can you scare up a transport for me?’ I asked.

Wagneer laughed at the idea. ‘In this? All right, I’ll see what I can do.’

The local militia took me overland to the pass in a Centaur, hooded against the rain and bulked out with yellow swim-bladders to allow for the fording of flash floods. The crew was not at all happy about the outing, but bit their tongues because of what and who I was. After twelve hours grinding along mud tracks and waterlogged gulches, they got me through the pass, over the iron bridge, and into Kulbrech Town.

As we crossed the old, rusting bridge, I watched the corposant crackle and dance across the posts and stanchions.

In Kulbrech Town, an odious shanty backwater, transit was arranged to carry me on the next leg of my journey. The Centaur turned back to Foothold. I went on in a cargo-8 that had seen better days.

‘There’s been killing, you know?’ the driver mentioned, conversationally.

‘I had heard something to that effect.’

The driver nodded. Tiny threads of static were playing across his knuckles as he nudged the wheel.

‘Four dead,’ he said.

I can honestly say that I quite admired Jared Commissioner Maldar Zelwyn. What he lacked in almost everything he made up for in sheer optimism. He showed me around Jared County Town personally, and made it clear he was tremendously proud of it.

The town straddled twelve river threads, and it seemed to be all bridges and decking and cantilevered platforms. Habs stacked up high above the steep, rain-river chutes. Water throbbed and rattled and chugged down the channels through the town on its journey from the hills to the sea. As he drove me across the New Bridge, Zelwyn proudly explained how he had seen to its construction five years earlier, for the benefit of the community. It was a large metal structure connecting the Commercia quarter to the merchantman residences, and was evidently a boon to working practices. Before the bridge, the merchants had been obliged to take taxi boats from their homes to the Commercia every day. The river it crossed was one of the largest and most powerful bisecting Jared County Town, and the New Bridge was equipped with elevating sections so it could lift to admit the passage of trade ships and other water traffic coming inshore from the coast to the warehouse docks. It was an impressive piece of engineering, lit up, as we rode across it, by the unending light-show of the Cackle. Zelwyn clearly worked hard to support and improve his community, at the back end of all creation though it was.

We drew up on the glistening wharfs of the Commercia, and got out of the bulky land car. Zelwyn was a stocky man in his late forties with thinning hair and a heavy, bushy moustache. He took a data-slate out of his overcoat pocket.

‘All the victims were discovered in the Commercia district,’ he told me. ‘Here’s a plan of the locations. It seems arbitrary to me.’

I agreed, but I didn’t say so. ‘Is there crime scene data? Forensic material?’

‘I’m having it processed for you,’ he replied.

‘And you’ve got four now?’

‘Two more since I sent my message,’ he confirmed.

‘Is there a pattern?’

‘Apart from the way they were killed?’ he asked, and shook his head. ‘There’s no connection between the victims, except for the area they worked in – a trolley pusher, a warehouseman, a junior mercantile clerk, and a whore. We haven’t been able to connect any variables. As far as we know, they didn’t know each other.’

‘But you have a theory?’ I asked him.

He nodded. ‘The killer lives somewhere in the Commercia.’

‘Because?’

‘Each killing took place at a time when the New Bridge was raised. There was no crossing to the merchant district. To me, that says it must be local.’

I nodded. ‘But just a regular killer, surely? Not an Ordo matter?’

‘We’ve had our share of murders over the years, inquisitor,’ Zelwyn replied. ‘My office handles the cases. But this… the random mutilation, the missing ears–’

‘What do you think that signifies?’ I asked.

‘Trophy taking?’ he suggested. ‘Cults do like to take trophies, I understand. Ritual, I suppose. It smacks of ritual.’

‘I reckon it might.’

‘Yeah, I thought so,’ said Zelwyn.

‘Why?’

‘You wouldn’t be here otherwise.’

The Cackle grew more fierce as night pushed in. When we left the Commercia, rain was beginning to fall, and sirens hooted, warning that the New Bridge was about to raise its hydraulic spans. The river was at flood tide.

I reviewed the victims in the frosty twinkle of the town morgue. Preservation methods in Jared County were not Ordo standard. The cadavers had been dumped in bulk freezer units, and came out on their gurneys caked in frost, their vulnerable tissues blackened and cold-burned.

‘Sorry,’ said Zelwyn, watching me work. ‘I wish… our facilities could be better.’

‘Forget about it,’ I replied.

I used probes and skewers on the frigid bodies, sampling and measuring. The hacking wounds, some so deep they looked like claw marks, were especially ugly. They smiled like happily parted lips, their mouths full to the brim with frozen black ice.

‘Cult work, then?’ he asked, after a few minutes. ‘Have I got a cult here I need to deal with?’

‘No, a hunter,’ I replied.

‘A hunter?’

I nodded.

‘What does that mean?’

‘Trophy taking is a hunter’s quirk – an ear, a finger, a lock of hair.’

‘But that’s ritual, isn’t it?’ Zelwyn asked.

‘Hunters have rituals too,’ I said. He looked downcast.

‘Not a cult thing, then?’

‘You sound disappointed.’

The Jared commissioner managed a weak smile. ‘Of course not. It’s just that I’d hoped I was on the money. I wanted to impress you. If this is simply some nut-job serial, I’ve wasted your time, and I should have known better.’

‘Not to mention,’ I added, wickedly, ‘that if this had been cult work, I’d have dealt with it for you?’

Zelwyn shook his head.

‘I’m sorry to have cost you a journey, sir,’ he said.

I felt rather ashamed of my attitude. I put down the probe, wiped frosted blood off my gloved hand, and turned to face him. ‘Look, I’ve nothing better to do. Let me help you anyway.’

‘You’d do that?’ he asked, rather taken aback.

‘Of course. Why not?’

‘Because you’re… you know…’

‘An inquisitor? Inquisitors don’t like serial killings any more than commissioners do,’ I said. ‘I have certain skills, Commissioner Zelwyn. I think I can bring this animal down.’

He smiled. It was the warmest, most genuine thing I’d seen in years.

I was just trundling the last corpse back into its freezer when a militia officer came into the morgue and whispered something to Zelwyn.

He turned to look at me. I felt his pain. I mean, I actually felt it. The psyker talents that would later serve me and shape my career were still raw and unshaped in those days, but my empathetic function nevertheless resounded at his distress.

‘While we were busy here…’ he began.

‘Talk to me, Zelwyn.’

He took a deep breath. ‘While we were fussing around here, there’s been another death.’

‘Is the body still in situ?’

He nodded.

‘Let’s see it.’

We had to wait for five minutes while the New Bridge lowered its spans to let us cross into the Commercia district. Zelwyn let one of his militiamen drive us. The Jared commissioner’s hands were shaking too much to be trusted.

Corposant lit up the bridge. The sky made strange colours that twisted and turned. Rain fell. The river below us rushed along, rich in sediment, towards the distant sea.

Lana Howey had worked the wharf for twelve years, and was a regular face at the drink-stops and taverns along the hem of the Commercia. She’d once been popular, a fast girl with good looks and impressive legs, but the work had taken its toll. In the months before her death, she had earned her income turning tricks for specialist customers, men who were more interested in what she was prepared to do rather than the way she looked.

Now she was dead.

Her body lay on the ground floor of a warehouse just off Commercia Main. It had been discovered by a night watchman. Slim, too slim, and wearing too much make-up, she lay naked and awkward under the over-bright portable lamps. The blood from the deep, slashing incisions had pooled under her in a slick. Her left ear was missing.

‘Same as the others,’ said Zelwyn, shuddering.

‘No,’ I said, crouching beside the body.

‘No?’

‘No, she’s still–’

I wanted to say alive, but that would have been wrong. She wasn’t alive anymore, but she was fresh, fresh compared to the freezer-burned residue Zelwyn had shown me earlier.

‘The hunter again?’ Zelwyn asked.

‘Looks like it. The ear, you notice?’

‘Why do you think it’s a hunter, Inquisitor Eisenhorn?’ Zelwyn asked.

‘The slash wounds,’ I replied. ‘You see? So deep. These are the kind of deep cuts that a hunter might administer to accelerate decomposition. A kill he doesn’t want, and which he wants to rot away quickly.’

Zelwyn pursed his lips. ‘What are you going to do now, sir?’

‘I’m going to ask you and your people to get out of this place. Withdraw to a sixty-metre perimeter.’

‘Why?’

‘Don’t ask me that, commissioner.’

‘I want to stay,’ said Zelwyn.

‘On your own head, then. Get your people out.’

Later on in my career, I only ever undertook auto-seances when I had a properly qualified astrotelepath to assist me. Such acts can take a toll. Back then, I was young and headstrong, and full of my own energy and will. It’s a wonder I ever survived.

‘Bolt the door,’ I said to Zelwyn. He obliged. His men had gone. ‘Do what I say and don’t interrupt me,’ I added.

‘Right,’ he said.

He stood back, near the heavy warehouse door, watching. I knelt beside the hacked corpse and sighed.

Outside, the Cackle sputtered and pulsed.

‘Lana Howey?’ I called softly.

I felt Zelwyn open his mouth, to ask why in the name of the Throne I was talking to a dead body. I think it was about then that he finally woke up to what was going on. I sensed fear bubbling up inside him, along with a strong desire to be outside with his men after all. He’d never seen anything like this done before.

‘Lana Howey?’

The warehouse air took on the glossy, cold feel of hyper-reality. The light refined in clarity, and small details became impossibly sharp. The various odours of the place: soot, rockcrete, oil, sacking, thinners and the body itself, were suddenly more concentrated, more pronounced.

‘What am I doing here?’ asked the late Lana Howey.

I heard Commissioner Zelwyn groan. I felt his gnawing fear.

‘Lana Howey?’ I called.

‘Hello, mister. What’s your pleasure, then, sir?’

‘Lana, my name is Gregor.’

‘That’s a lovely name. Gregor. You’re a handsome one for sure, Gregor. What can I do for you tonight?’

‘Where are you, Lana Howey?’

‘I’m in the warehouse, with you, silly man. This is my place. Don’t you fret. It’s quiet here, discreet. You’re a regular, aren’t you? I know your face.’

‘You’ve never seen me before, Lana Howey. You’ll never see me again.’

‘I doubt that,’ she sniggered. Her chuckle was the scratchy glee of the Cackle. ‘I bet you’ll be back again for more, soon enough.’

‘I need you to focus, Lana Howey,’ I said.

‘Focus? What? Why do you keep using my name, my whole name, like that? Is that your thing, mister?’

+Lana?+

I felt Zelwyn fighting back an urge to throw open the door bolts and run. I really hadn’t wanted him to be here in the first place. All he could see was me kneeling beside the body. He could not see what I could see.

An after-image of the victim had appeared to me. She was wearing a cheap, revealing dress and had taken a seat on a nearby freight trunk, one leg crossed over the other. The raised foot was swinging impatiently.

+Lana? Can you hear me?+

‘How do you know my name, mister?’ the image asked, watching me.

+Administratum files. Lana, who was it?+

‘Who was it that what? Come on, I’ve got punters waiting. What are you on about?’

+Lana. Please let me see. Who did this to you?+

‘Who did what to me? Look, I haven’t got all night,’ she breathed. ‘Show me some money, mister.’

I reached into my pocket and produced three crowns. The air was very cold. My breath was steaming, and so were the open wounds on the corpse in front of me. On the trunk, image Lana swung her leg.

‘That’ll do it,’ she said. ‘What do you want? Full service, all the stuff?’ She stood up abruptly and reached down to pull her dress off over her head. It was only then that she seemed to notice the body on the floor.

The image stared down at it for a long time, her hands frozen in the act of bunching up her dress to drag it over and off. When she looked at me again, her eye make-up was blotted and running.

‘When?’ she asked.

+Not long ago.+

‘Oh, Throne. What did I ever do to deserve that?’

+Nothing. Lana, I want to know who it was. Will you show me?+

She showed me.

She showed me, her voice growing steadily quieter and quieter, and when she was done, she faded altogether without any protest, casting me one last, hurt look with her make-up-stained eyes.

I took off my storm coat and laid it over the corpse.

Outside, dawn was no more than an hour away. The rain had eased off and the Cackle had dropped in intensity. Zelwyn stood by the waiting militia transports, taking repeated draws from an old hip flask. When I walked up, he offered it to me. I took a big swallow.

‘Are you–?’ he began

‘I need a moment.’ The work had drained me, not so much sapping my will as abrading my emotions.

‘Can the details move in, at least?’ he asked.

I nodded. Several militia officers and two coroners with a stretcher went into the warehouse at Zelwyn’s nod. After a few minutes, someone brought me my coat.

I gestured to Zelwyn and walked away in the direction of the New Bridge.

‘It’s a good thing I stayed,’ I told him. ‘This turns out to be an Ordo matter after all.’

‘A cult?’

‘No, and not a hunter either… At least it could be either of those things, but that’s not what makes it an Ordo matter. We’re dealing with a regia occulta.’

‘Hidden way,’ he translated. Zelwyn was no fool, he had High Gothic.

‘That’s the literal translation. In the Ordo Malleus, it has a more specific meaning.’

‘Go on.’

‘A regia occulta is a pathway… A tunnel or portal, if you like, that links our reality with that of the warp.’

‘Is it a deliberate thing?’ he asked.

‘Perhaps. Cults and heretics do sometimes open them deliberately. But it could be a natural occurrence. Most are. The fabric of space is thin in places, you see, and sometimes there are leaks.’

He shook his head and a sad smile appeared under his heavy moustache. ‘I don’t actually know much about the warp, sir,’ he said.

‘Nor should you, commissioner. It’s forbidden lore. I’m just telling you what you need to know. There is a regia occulta in Jared County Town, and it’s right here.’

We were standing at the Commercia end of the New Bridge.

It took Zelwyn just a few minutes to have the bridge and its feeder roads closed off and barricaded by the militia. Another hour, and it would have been teeming with traffic heading in for work.

‘Can you tell me why this only happens when the bridge is up?’ Zelwyn asked. ‘I mean, surely that would block a crossing?’

‘I’ll do better than tell you,’ I said. ‘I’ll show you.’

We took up a position at the Commercia end; me, Zelwyn and four men from the militia armed with powerful autorifles. At my nod, the commissioner signalled to the bridge machine room on the far bank, and the operators engaged the hydraulics. Ponderously, with a dull squeal like gates opening, the massive spans began to lift.

The Cackle fluoresced in the dawn sky over our heads. Blue ropes of fizzling corposant writhed and trickled like snakes around the iron finials of the bridge towers, and traced their way along the rising edges of the gigantic metal spans.

The hydraulics cut out when the spans were at a standard lifted position, at about forty degrees from the horizontal. We waited, looking up the steep metal slope of the span facing us. Below us, out of sight, the fast-running river gurgled and hissed.

We waited for ten minutes. Corposant gathered in increasingly heavy ribbons around the raised tips of the bridge span, as if attracted there in concentration, like lightning drawn to a conductor.

There was a dry electric crack, and we smelled ozone. One of the militiamen pointed. A whip of corposant had flicked out from the tip of one span and connected with the tip of the other, like a squiggle of electrostatic voltage crackling between two insulated orbs. It remained there, jerking and sizzling, like a bright, twisting rope tying the two halves of the raised bridge together. This feature had not been evident in the patchy disposition Lana Howey had shown me, but I suddenly felt I had discerned the key mechanism of the infernal regia occulta.

One of the militiamen started to say something, but I already knew ‘it’ was happening. The hairs on my neck were raised. I felt something akin to a ball of ice in my stomach, and a searing pain behind my eyes.

The killer came into view. He simply manifested out of nowhere, as if the air had parted like a curtain and let him through. He appeared high up on the span ahead of us, and began to plod down the steep slope. He did not see us at first. We heard his feet slapping heavily on the metal roadway.

Though humanoid, he wasn’t human. I was the largest man in our party, and he was twice my mass and half my height again. He came wrapped in a heavy, ragged cloak of animal skins with a hood drawn up. His shoulders were very broad.

The pain behind my eyes was getting worse by the second. I could barely focus.

‘Kill it,’ I said.

We opened fire: four military-grade autorifles, firing reinforced rounds with fifty per cent more grain in them than standard, Zelwyn’s lasgun, and my Tronsvasse assault pistol. The noise was stunning, and the muzzle flash a strobing flutter. The killer was dead in just a few seconds. Our firepower tore him apart and shredded his foul cloak, though he possessed such astonishing strength that he actually managed to walk into our fusilade a step or two, trying to shrug it off, before it overcame him.

He fell heavily, and rolled down the slope.

‘He’ was a mature ork warrior. Released by his spasming paws, a huge cleaver and a large metal cudgel lay on the roadway beside him. We approached slowly. Greenskins are notoriously hard to kill, and though we had blown this one wide open, I fired three more rounds into its skull to be on the safe side. Ichor, almost black in the dawn light, ran down the slope. The mangled corpse showed signs of body paint, tribal markings and lots of crude piercings and bangles. Fresh human ears were strung around its throat on a wire.

‘A greenskin?’ Zelwyn murmured. ‘But this isn’t green space. There haven’t been any orks in this sub for generations.’

‘It didn’t come from this sub,’ I said. I was finding it hard to speak or concentrate. The pain behind my eyes was even worse than before. It felt like a hot wire. ‘It came from whatever random site this regia occulta connects to. This beast went hunting one day, and ended up here. We’ll never know, I fancy, where… where…’

‘Inquisitor? Inquisitor Eisenhorn?’ I heard Zelwyn say. I felt his hand catch my arm. The pain behind my eyes had turned into full-blown psyk agony. I could barely stand, let alone speak.

And I really wanted to speak. I needed to. I needed to yell out, ‘It’s not over!’

The regia occulta was still open. While we had been standing there, gawping at the ork’s cadaver, a second one had walked in through the hidden way.

For such a massive thing, it moved very fast. I moved like lead, transfixed by the pain the seething warp gate was lancing into my receptive mind.

I heard a feral roar, and smelled a foul animal scent. I fell, shoved aside, I think. An autorifle fired.

The ork slew the first militiaman as he landed among us, splitting the fellow straight through the crown with his jagged cleaver. The man collapsed under the force of the blow, his sectioned skull spilling open as the blade jerked back out, his heels drumming the ground. The ork caught another man by the throat, yanked him off his feet, and bit away his face.

It is awful to reflect that this unfortunate lived for at least another ten minutes.

The ork broke the back of a third militiaman with a stinging cudgel blow, before making off in great bounding leaps towards the unlit buildings of the Commercia. Zelwyn and the sole remaining militiaman fired after it. The man with the broken back lay on the ground, screaming.

‘Eisenhorn?’ Zelwyn yelled.

+Lower. The. Bridge.+

I didn’t want to use my will on the poor fellow, but I had no choice. My mouth wouldn’t work. Zelwyn wet himself as my mind intruded upon his. To his credit, he rallied and signalled the machine room.

The New Bridge slowly rattled and clanked back into place. The corposant charge between the spans shorted out and vanished as the opposite ends touched.

My mind cleared at once, the pain draining back. The regia occulta was shut.

Blood had streamed out of my nose and soaked the front of my jacket. I got up and ran towards the warehouses. The ork had vanished from sight. I had to find it, before it found anyone else. A greenskin is dangerous enough. This one was enraged, possibly wounded, and knew it was cut off and pursued by its mortal foe, man.

Zelwyn ran after me. The remaining militiaman stayed put, too shocked to move, his rifle limp in his white-knuckled hands.

‘Get back, Zelwyn!’ I shouted. ‘Gather your militia in full force.’

‘Like hell!’ he yelled back. He shouted over at the units waiting behind the barricades, and they moved forwards after us. We entered the most likely venue, a warehouse stacked with mineral hoppers. Glow globes hung from the rafters, but not all of them worked. Frail daybreak glimmered through the rooflights.

‘In here?’ Zelwyn whispered, panting.

I held up my hand for hush. The place was quiet, except for the mocking chuckle of the Cackle. I tried to reach out with my mind, but I was drained, and no human psyker can read the greenskin mind. They are blunt to us. I took a deep breath instead, and smelled the air: mineral stink, wet rocks, and a hint, just a hint, of animal odour.

We edged forwards. I saw dark, wet spots on the rockcrete floor, leading between the piled hoppers. Unless someone had recently carried a leaky promethium drum through the place, Zelwyn had managed to wound the creature right enough. I touched one of the spots. It oozed warmth.

‘It’s here,’ I whispered.

Zelwyn already knew that. It had come out of the shadows, nightmarishly silent for something so big, and seized him by the throat. I turned slowly.

The ork had pulled the Jared commissioner in against its massive chest like a mother hugging a baby to its breast. Its left paw entirely encircled the man’s neck. Zelwyn’s eyes were wide, and his face was pale. The ork raised its right hand and gently rested the massive cleaver on Zelwyn’s scalp. Tiny trickles of blood ran down Zelwyn’s face.

The bull-ork’s yellow eyes, deep in the brow-ridged sockets, glared at me. Its heavy, flaccid lips wrinkled and twitched. Its tongue, huge and greasy, worked behind its rotting peg teeth. Each one of those teeth was the size of my palm.

The ork was not a bright beast, but it was smart enough, instinctive enough, to recognise its predicament. It was bargaining with me, a life for a life. This much I knew. Otherwise, Zelwyn would have been dead already.

I thought about taking a shot, but dared not risk hitting the commissioner. I was too spent, and it was no time to try my aim. Besides, greenskins are notoriously hard to kill. Even if I hit it, one round from a Tronsvasse would not do the trick.

All I had was my will. I couldn’t impel the ork in any way, but Zelwyn was a different matter.

Without hesitation, I reached into the commissioner’s panicking mind. He was still clutching his laspistol, dangling at his side. I squeezed his finger for him. The shot blew clean through the arch of the ork’s slabby right foot.

The greenskin convulsed in pain, but I already had a grip on Zelwyn’s motor function, and I threw him forwards. I felt his astonishment as his body acted without his permission. He flew out of the ork’s briefly weakened grip so fast and hard, he careered forwards and bounced face-first off the hopper to my right.

I was already firing, my weapon braced in a two-handed grip. I emptied the assault pistol’s clip into the greenskin’s chest, filling the air with drenching black mist and driving the monster into the stack of mineral hoppers behind it. It smashed heavily into the metal siding, but remained on its feet.

I ejected the dead clip, and let it drop and clatter to the floor as I snapped home a reload from my coat pocket. I tore off the second clip in one go, firing into the ork’s face and neck. The back of its vast skull banged repeatedly against the hopper behind it. Spray-patterns of ichor splashed out across the hopper’s side.

It swayed, then took another step towards me.

‘Oh, for Throne’s sake,’ I hissed, ‘just die.’

It died. The stack of hoppers, unsettled by the repeated impacts, creaked and toppled, crushing the ork in an avalanche of rock ore, clinker and iron crates. The noise was deafening. I shielded my face. Dust billowed up, and slowly settled.

I helped the Jared commissioner to his feet. He was quaking badly. Both of us were coated with a film of rock dust. He looked at the mangled heap of wreckage, where dark, clotted ichor seeped out from under the heaps of spoil.

‘Holy shit,’ he murmured.

There was no way, or no way in the understanding of the Ordos, anyway, to close a regia occulta. I made it quite clear to Zelwyn that the New Bridge should never, ever be raised again, for it was that very raising, during the Cackle, that produced the unique combination of effects necessary for the regia occulta to function. He needed no persuasion. The day before I left Jared County Town, he had the machine room dismantled and the heavy gauge hydraulics uncoupled. I understand, though I cannot confirm the fact, that the New Bridge was swept away in a freak flood tide some years later. It was never replaced. The regia occulta never reoccurred in Jared County Town.

Commissioner Zelwyn, who went on to serve his community for six and a half decades, kept one of the ork cleavers on his office wall, and enjoyed telling visitors that the dried blood on its points was his.

The morning I left, he came to see me off.

‘I hope I never see you again, inquisitor,’ he said, shaking my hand.

‘I hope so too, commissioner.’

He paused. ‘I meant that in a good way,’ he added.

‘So did I,’ I said.

I crossed over into Foothold County via the pass at Kulbrech. The reluctant motorised unit of the local militia was there to meet me, the engine of the Centaur idling. They weren’t glad to see me, but I was glad to see them. The Cackle was dying away, and I would soon be gone from Ignix.

The Cackle was dying away, but it insisted on having the last laugh. Many years later, at the end of my life, the mocking elements of Ignix would return to haunt me. But this was – oh – 223.M41, and I was only just out on my own.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...