Only in a time-locked building like the Woodbine Crown Mall would you see a HELP NEEDED sign in a shop window.

Not HELP WANTED.

Needed.

It was handwritten on the back of a piece of what looked to be torn wrapping paper and taped to the glass, at an odd angle. Shell stood outside the florist, her groceries and gravity tugging red crevices in the palms of her hands. Well. Her mother’s groceries. Not what she’d choose for dinner, but it wasn’t Shell’s kitchen, or Shell’s table.

HELP NEEDED.

Shell’s own voice inside her head had been so loud lately. We all need help. She imagined that whoever it was running a dank little flower shop in the Woodbine Crown probably needed a fair amount of help. Maybe not more than her, necessarily. But more than most.

The mall was almost exactly as it had been since Shell was a child, or before, even. Three wings, and the great glass terrarium in the atrium, murked with moss and condensation. This would have been a gorgeous feature if it hadn’t been there for thirty years and never seen a lick of window cleaner. A three-pointed crown with a strange old emerald at the centre, it was a late 1970s relic, an aspiration towards American luxury retail ambience transplanted deep in the veins of the Northside Dublin suburbs. An architectural curiosity. Three floors. The local Dunnes Stores, a library, and a radio station. An enormous fountain in the centremost wing that had been gathering copper-wish pennies to no apparent cause. No functioning elevator. A kip, Shell thought. A weird kip in a nest of housing estates. A heaving, dilapidated heart at the middle of a wire grid of old veins. The terrarium, the sick heart within the sick heart. Sick hearts all the way down.

Not a single part of it had ever been knocked and rebuilt in Shell’s lifetime. No new lights installed. The linoleum tiles on the floor, mostly a dappled beige, except those that had failed under endless footfall, which were replaced at random with incongruous glitchlike patches of red or black. The ceiling was low, but in such a way that a person would hardly notice until they perhaps had been inside for an hour and were met with the strange sensation that they were miles away from daylight. The unit layout was, seemingly, unplanned. It all made Shell feel a bit sick, generally, some low nausea that could have been repulsion at poor design instilled in her at art college, or the unshakable awareness that she was, well, back home. Back here. She’d never had any intention of being anywhere of the sort. She didn’t know whether she hated it truly or was just heartbroken. She couldn’t tell yet, but either way, it was smothering, all of it.

What had happened in January should have freed her, but it trapped her back here instead, and she felt her eyes well up and wasn’t it too far into everything to be still crying? Summer racing up on her. HELP NEEDED nearly set her off, but she couldn’t cry here. Everyone watched everyone as they stepped in and out of the shops, the bookies, stopped at the coffee dock or sat over a plate of deli breakfast at Keeva’s Kitchen in the scant food court under the huge, cold skylight, peering at other people’s groceries through any thin spots in plastic carrier bags. Shell pulled her neck scarf up over her chin for comfort. She could at least pretend to be invisible then. Pretending was half the battle.

Even without the fabric over her nose and mouth, there was a thick in the air that you couldn’t condition out, a gelatin feeling, suffocating. It made Shell feel like she was eight, fourteen, and perhaps like she was seventy-two and still here, in a shopping centre adjacent to her housing estate, still here, still in this place. Something wouldn’t let her leave this part of the world and she had worked so hard to get gone. She had almost escaped.

She looked at the flowers in tall green buckets outside the florist that needed help and thought to herself that she would buy some and at home she’d draw them. They would cheer her parents up, act as a casual token of gratitude and appreciation, and keep her off her phone for a few hours tonight. They would also act as a very helpful excuse to inquire about what kind of help was needed, exactly, in this flower shop.

A graphic design job like her old role at Fox & Moone now was as good as a pipe dream: a situation that felt impossible to replicate. The listings Shell found were all for entry-level positions that somehow required five years of campaign experience, or executive roles that held no appeal to her, even if she had been qualified. She was stuck in the house with too many other adults: her sisters, her parents, too many of them in the space all day. Annoying one another. Her sympathy pass had run out weeks ago; now she was an interloper. It wasn’t like she hadn’t been looking for work. It was more that she’d been sending miserable emails to friends, peers, friends-of-friends, trying to suss out if their companies were hiring and being met with more unemployment, more bad news.

So sorry to hear about you and Gav, such a shame about Fox & Moone, just between you and me we’re actually letting so many people go right now, love a recession, lol, I’m sure you’ll be snapped up in no time babes x

Eventually, they stopped asking at all how she was getting on with the hunt.

Every message she got back from every query hit the same beats. They might as well have just said: Sorry to hear about your life, but I’ve got nothing for you, someone else might, I suppose? Over and over, until all of Shell’s long-treasured favours were tapped out, and she was left staring into her laptop all day, scrolling, hope numbed, unable to cut back any self-pity. She’d have emigrated already if she had the money.

Her mother had expressed concerns about her going off and starting over at her age, at thirty-three—but what about Galway? That would be far enough away for a new beginning but near enough home, too. Just across the belly of the country, the other coast.

Still, even that kind of move was steep cash, and as much encouragement as her mother gave her, there was no world in which Shell was being bankrolled. Shell was to sort herself out.

So, sorting herself out could look like retail. Forty hours in a shop a week was preferable to the wallowing, to the endless pingback of So sorry hun. Minimum wage would be a slap, but one she could take. Floristry was the same as design, right? The meticulous organization of beautiful, delicate things. Shapes. Shell liked shapes. She scooped a heavy bouquet—expensive, but best to look like that wasn’t an issue—from a bucket out front and walked inside. One arm weighted down with carrots, six densely wrapped chicken breasts, and a large tub of gravy granules in a cloth bag, the other cradling a carefully-organized-to-look-kind-of-wild clutch of sunflowers, eucalyptus leaves, ferns, and some mad, virgin’s-cloak-blue blossoms she couldn’t name.

The shop was a little larger than the walk-in wardrobe she’d shared with Gav, back at the apartment. The ceiling just as low. Lit funny, yellow almost, by multiple lamps instead of one overhead light. It was so cold, so suddenly, that Shell felt a chill go over her and her nose turn pink. The shelves were jammed with wreaths, succulents, swags. Buckets on buckets, some tall, some stout, rammed with flowers, organized by species, not colour. Pots and pots of monstera, the kind you see a lot of on Instagram now that nobody leaves their house so much anymore. Talk radio played at a low volume, almost inaudible, but Shell just about caught the jingle: Woodbine Crown FM, afternoon vibe at 106.9! There was an almost-chaos to the place: it was overrun with life. Well. Not life. The flowers were dead the second they were cut, weren’t they? Shelly supposed nothing in here was alive, only a handful of potted plants and herself.

However, it was not just Shell and the merchandise. Down the back of the lush, close den was a high counter, and perched on a stool behind it, reading a book, was the florist.

Shell knew the outline of her, somehow. Had they been in the same school? A few years apart? It wasn’t until the florist looked up from her reading and right into Shell’s eyes that she started to feel in any way nervous. The florist closed the book, tilted her head to the side, and said, “Delphis and sunnies. A dream. Let me stick a little extra paper around those for you.”

Shell smiled, handing the bouquet over the counter, hoping her cheeks would lift the signal to her eyes, and said, “A dream, thank you. Do you mind me asking—like, sorry—what kind of help do you need?”

The florist laughed, husky, unspooling brown paper into a square. “That’s a big question.” She laid the flowers down to wrap them.

“I’m unemployed,” said Shell, before she could think, and the florist, taking a thumb of tape from a large black dispenser, said, “Oh, the sign,” in a voice that made Shell feel as though she’d missed a joke and said something incredibly stupid at once. The florist quickly swaddled the bouquet with the paper and taped it in place. She stood the flowers up on their stems, the bunch finding a stable geometry, flourishing with light petals at the top, bound into a hinge and all the weight low, in the green legs. They both admired them in silence, for a moment, the gold and the blue and the green. The wild and the order.

The florist was taller than Shell and her hair was cropped short. It was dark—perhaps it would have been curly if it had been long, and Shell was very aware then that she was looking at her, properly, trying to decipher why it was that she felt like she knew her. She wore small glasses, but her features were large. Her eyes and her mouth were generous.

“Are you interested?” the florist asked, looking at the bouquet, adjusting it slightly.

“Sorry—what?”

“Interested. In the job. How do you feel about flowers?”

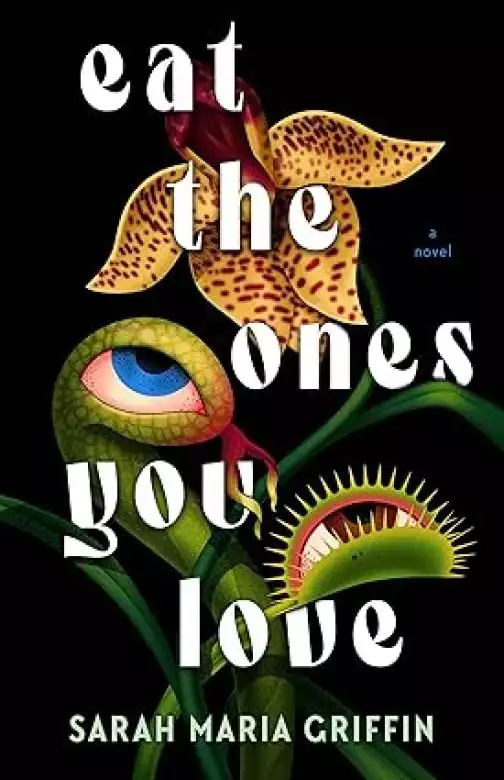

Copyright © 2025 by Sarah Maria Griffin

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved