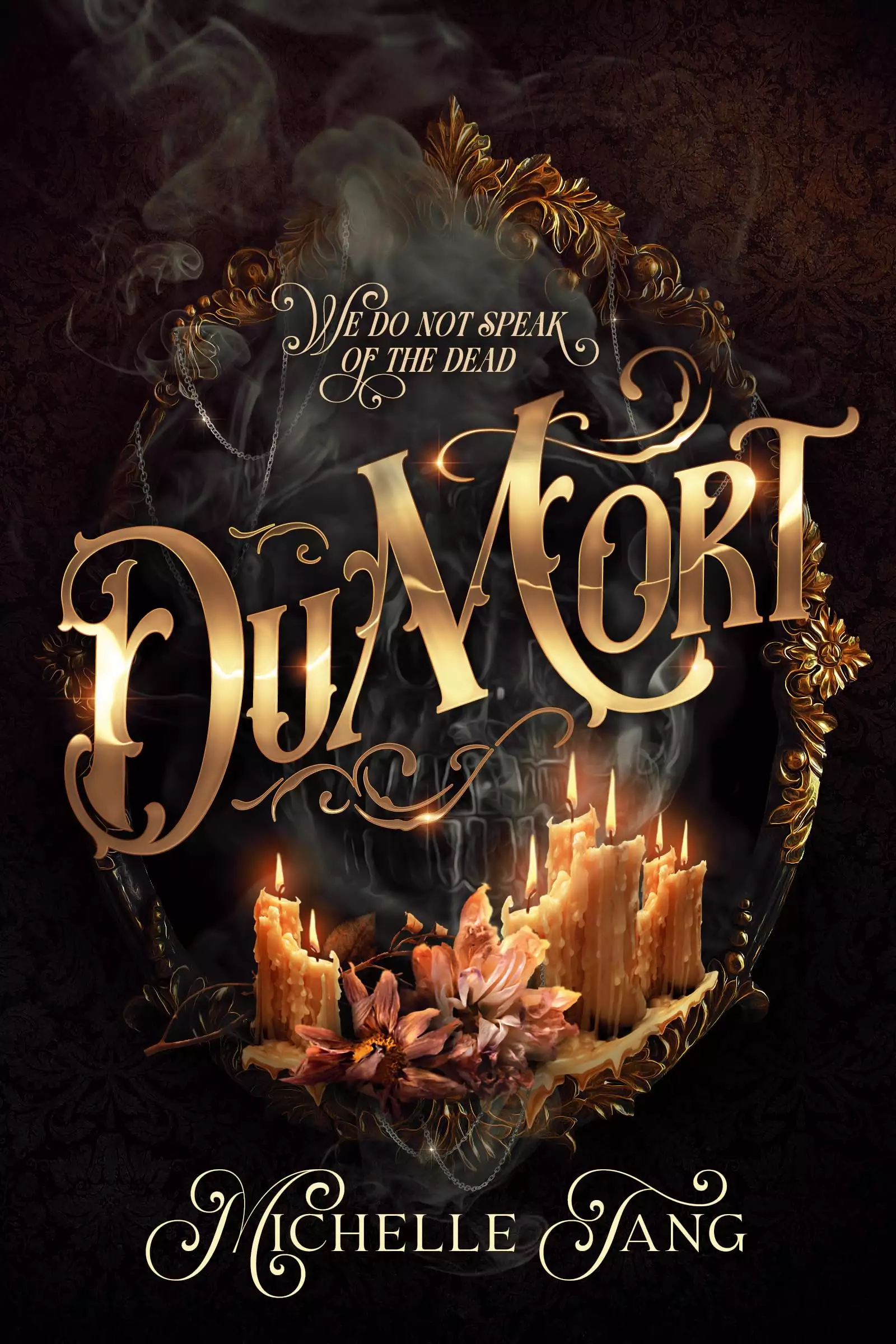

“In Mydalla, we do not speak of the dead.”

SuChin left bruises around my neck, delicate blossoms budding purple beneath my skin which no amount of powder could hide. I hooked the stiff, high collar of my brocaded cloak closed and turned from my mirror. Hoped it would be too dark for mortal eyes to see the violence my sister’s ghost had inflicted.

“I will be out for a few hours,” I told Edgar, and waited for a sign that he cared. His eyes did not leave his book to glance at the gathering dusk; neither protest nor question passed his lips. And so, heavy-hearted, I passed through our front door.

The horses’ shoes tapped a nervous rhythm, a secret code warning me to turn around. I rode through the streets, the carriage wheels bumping over wet cobblestone, lanterns that stained the evening fog a sickly yellow marking the distance. Rolling estates gave way to smaller, closer buildings, and soon a wall of narrow houses loomed over the road, their windows staring like unblinking eyes.

Beyond these structures, in the centre of Mydalla, the massive cathedral gazed upon the city like a benevolent god. The holy crematorium’s four marble spires reached upwards to the skies, decanting precious souls into the heavens. Squatting alongside their brilliant glory like an ungainly sibling: the Bastille, constructed of black, rusting steel. It loomed like a threat.

Like a warning.

I turned my eyes from the ominous sight and steadied my breath.

When the carriage stopped, no one came from the private home to greet us. My driver clambered down to open my door himself. “Are you sure this is the right place, Mrs Braithwaite?” he asked as he helped me down, his tobacco-scented breath forming pale miasmas in the chill night air.

I nodded. Clenched my gloved hands around my skirts, but my disobedient fingers would not stop their trembling. My stomach churned, as if swirling to my fingers’ rapid tempo. It was not fear that made my body shake, not really: it was hope.

But I had encountered hope before, followed closely by its child, despair.

“I was told he would be here.” My voice was hoarse. “Stay here until I return, won’t you?”

My cloak’s gold threading caught the lantern light as I approached the house’s entrance, the jewels scintillating like small stars. I would be overdressed, of course, but I had long learned it necessary. The house was a modest one, grey rough stone and black-lacquered door, the surname WILCOX carved into the lintel of the frame. The house was quiet, like the others I had passed, but dim illumination behind the windows revealed many silhouettes, and there was a sense of movement

within.

I knocked with the blade of my fist. Miss Mina Kwan had never been meek, despite her humble beginnings, and Lady Mina Braithwaite was thrice as bold. A pause, evident even in the silence of the house, and then the faint vibration of footsteps neared the door. Courage, I girded myself, and fought the urge to neaten my hair or to smile.

A manservant greeted me, his gaze first falling on the midnight black of my hair, then lowering to my dark, slanted eyes and gentle nose; his own eyes widened as he scanned my rich clothing and fine jewels.

I lifted my chin; hoped my collar high enough to hide my throttled neck. “I understand the great occultist DuMort is a guest in this home this evening. It is imperative that I see him.”

The servant shook his head politely. “Occultist? This is a law-abiding house, my lady. This is only a small gathering of the host’s closest friends.” There was a minuscule hesitation before he addressed me as lady, but I was well-used to hearing it.

I swallowed down my doubt and squared my shoulders beneath my cloak. “Then I am most grateful for the host’s indulgence.” I stepped forwards as if nothing would stop me, and the servant did not dare shut the door against my approach.

The night’s cold air slipped past me to announce my arrival, and the people nearest the door turned towards me. There were no faces I recognised, no acquaintance to corroborate the rumours that would be birthed on this night, no friend to shame me back towards decency. I stalked from the foyer to what was a sitting room: a vase of flowers adorned a table between the guests seated on couch and twin armchairs, the flowers’ colours muted into grey by the scant light. Shocked silence followed in my wake. My booted footsteps sounded unbearably loud against the wood floors. It was the only sound in the house, as if I were the ghost and the people around me were rendered mute by the horror of my intrusion. The rooms were dark, but a

fire crackled in the hearth and candle flame flickered here and there, enough light to make the intricately carved baseboards and crown moulding visible. Framed paintings decorated the white walls, but I did not linger to admire them: there were too many bodies in the way.

I hesitated by the base of the curved stairway, unable to summon the courage to mount those steps to private bedrooms. Even I, in this most desperate of times, could not stoop to that level of impropriety.

DuMort had to be here. I had risked my husband’s name with this action, faced certain humiliation, and it would all be for nought if I couldn’t speak to the man.

A tall stranger approached me, surely the host himself. He spoke politely at first, but as I ignored his questions and stepped around him, he soon grew impatient and took hold of me.

He marched me back towards the door, past the unfamiliar faces which brightened with glee at my capture, and though my cheeks burned, my eyes did not stop their search.

There.

In the second room I’d rushed through, a sixth sense alerted me. I paused, halting the host mid-step lest he hurt me. My eyes were more accustomed to the dark by now, and the shape of a man coalesced behind the lone round table, behind the single candlestick.

It was DuMort.

I knew him at once, though the room was dim and he sat in the shadows. The poorly drawn posters that floated about town did not do him justice. In this room full of people, his very presence throbbed like a heart. A darkness emanated from him, a ravenous void that devoured everything, pulling gazes and people towards him. I could easily see him communing with the spirits: they, too,

would be drawn by his magnetism.

I pulled away from the gentleman’s firm grip on my shoulder and threw myself towards DuMort. He was the only one seated at the round table; his black garment merged with shadows that the candlelight could not chase away, until he seemed as vast as the room, ethereal as the night itself. The high collar of my cloak choked me as I lunged, until with a ripping of threads and gasps of disapproval, the fine garment fell away to hang, like a chastened child, from the host’s hand.

“Please, sir,” I said to the occultist, staring into the dark hollows where his eyes must be. “I beg for your help. It is a matter of life and death.”

DuMort’s expression didn’t change, but his gaze shifted from my face to my neck. My neck, offering him a bouquet of purple petals. Voices floated around us like snowflakes: ice-cold and fleeting.

“She has no shame at all.”

“What does one expect from someone like her? One can’t rise above their station.”

“Who lent the servant a dress?”

We were in a snow globe, DuMort and I, in a world of our own, entertainment to our observers.

A firm hand gripped my wrist and yanked at me. “This is a private gathering, as you have been told.” This must be the Lady Wilcox, here to do what her husband dare not, and throw a pitiable woman onto the street.

I did not look back at the occultist as I was led away. He had heard my plea, had seen the severity of my case, and I had done irredeemable damage to my husband’s name if anyone were to identify me. ...