- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

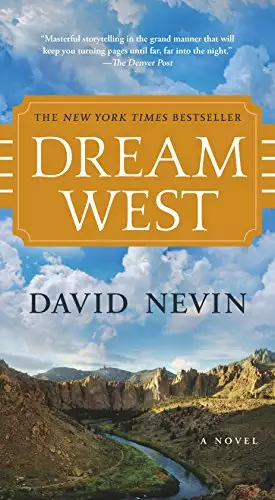

Dream West is the New York Times bestselling fictional account of famed North America explorer John Charles Fremont, by David Nevin.

Upon its release over twenty years ago, Dream West was deemed a classic novel of the American West by both critics and the reading public. Telling the amazing true story of America's famed explorer, John Charles Fremont, and his beloved supporter and muse, Jessie Benton, it quickly found its way onto the New York Times bestsellers list and adapted into a CBS mini-series starring Richard Chamberlain. Now available for the first time ever in trade paperback, Nevin's epic of adventure and discovery will once again give readers a chance to witness the passion of an early explorers dreams of the great unknown, and the love and perseverance that saw his dream come to life.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: December 5, 2017

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 640

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dream West

David Nevin

They passed into a shallow draw with saddle leather creaking, and were letting the horses drink when an antelope with high pronged horns burst from a wild-cherry copse. Not ten yards away it stopped and stood motionless, gazing at them with eager curiosity, its head thrust forward, its round black eyes brazen and bright. The frozen moment, the animal tight as a quivering spring, struck Frémont like a vision. He saw a vein throbbing in its white neck and he felt his own heart in cadence. Then the antelope sprang sideways and was off, sailing over the prairie like a low-flying bird.

“We’ll see buffler soon,” Louison Freniere said. “Antelope are always bold when buffler are about. Beyond that ridge, I wouldn’t doubt.”

Buffalo. Ahead the ground rose in a steady sweep to a long dominating ridge a half-mile distant. Frémont stared at it; his pulse had not slowed and he smiled.

Both men were well mounted and each led a fresh horse already saddled for the chase. They passed a prairie-dog village where hundreds of the little yellow animals stood yelping at them, their short tails jerking with each cry. A gray owl with white-ringed eyes gazed imperturbably at Frémont from a burrowed mound. It looked strangely calm.

“Yes,” Louie said, almost to himself, “I can feel ’em.” He glanced at Frémont. “You’ll be on your own then, Charlie. Pick you a cow and hold to her—you’ve got to run that horse like you was running on your own two legs. Never mind the breaks and draws and them damned prairie-dog holes. Think you can cut yourself loose like that?”

“I’m ready,” Frémont said. He took a deep breath. Ever since St. Louis, all the way up the Missouri to Fort Pierre on the fur company steamboat and out across the wide open country of the Dakota Sioux, he had been waiting for his first sight of the legendary herds that blackened the land. Buffalo—Freniere and the others on the expedition seemed to think of nothing but that thundering sport and princely food of the plains. It was dangerous—the galloping horse was half blind in the dust, and if you fell, likely you’d be trampled or gored—but the danger was half the fun.

“Hell,” Freniere said, “you ain’t never ready for buffler till you come up on ’em.” He was half-coaching, half-challenging. “You’ve got to run, understand? Horse is faster, sure, but a buffler can run all day, run the best horse right into the ground. Slap leather once and there goes your chance.”

On the first day out Freniere, himself a magnificent horseman, had caught Frémont grabbing for the big Spanish horn on his saddle and he never let him forget it. But Frémont had learned a lot in ten days. Now Louie was sitting slouched in his saddle, throwing quick glances at Frémont and talking in bursts.

“Horse is no fool, you know. And he don’t really give a damn if you get a buffler or not—he ain’t going to eat none of it. He’ll take you up and give you a shot, but he’s sure as hell got to know you really want to go. It ain’t no time to tuck your butt.”

“Tuck my butt?” Frémont said, suddenly nettled. “The day you see me tuck my butt, you can have my gold watch and pistols.” He wondered if he sounded hollow.

“Well, you ain’t never gone after buffler before,” the hunter replied. He grinned, wolfish and keen, and Frémont saw that he was nervous, too.

It was coming on noon and the sun was high in a white sky. Light burned over the ridge and pressed down against Frémont’s eyes until they ached. He tugged his hat brim low; he could see mile after mile of endless, unmarked prairie, rolling like a troubled sea. High overhead an eagle circled on motionless wings, a speck in the vaulting sky. It was a land to set a man free.…

They were halfway up the long slope. Grass grew in tufts and clumps, gray-green and stunted but strong enough to keep a horse going forever. Little puffs of dust rose under the horses’ hooves and blew instantly away. The dry air made the wind feel cool, but a trickle of sweat formed under one of Frémont’s arms and ran down his side. Louie, staring ahead, had lapsed into silence. His brass-bound rifle lay across the pommel of his saddle and unconsciously the web of his hand fitted itself to the hammer, ready to draw it down on cock.

Louie was about Frémont’s age, maybe twenty-five, a lean, tall man, dark face burned darker by the open, long black hair falling to his shoulders. Once Frémont had asked him why he didn’t cut it. “What,” he said, “and break the hearts of half the girls in St. Louis? It’s right purty, Charlie, when it’s combed out, and there’s no shortage of belles who want to comb it.” He was wearing blue homespun trousers over rough boots and a buckskin smock belted at the waist. It was nearly black with age and grease and was molded to his shape. Most of the fringed whangs that might once have shed water in the rain were gone.

It was nothing like the gorgeous suit Freniere had worn the day Frémont joined the expedition in St. Louis. That suit was of buckskin too, but clean, soft as glove leather, worked until it was almost white. Its whangs were all intact, rippling a full six inches, and the shirt and matching moccasins were brilliant with red-dyed porcupine quills and the beadwork of the northern Sioux. Some patient woman far up the Cheyenne River had made it—and doubtless given Freniere her heart as well.…

It had been sunny and warm in St. Louis on that day in early May. They had been lounging in front of Pierre Chouteau’s American Fur Company, where the expedition was outfitting. These warehouses of gray stone had supplied the western fur trade for three decades, but now the compound just off the levee was quiet. The men had assembled for a final muster and Frémont, who had arrived so late from Washington he’d nearly missed the expedition, was getting acquainted.

“They got buffler in the Smoky Mountains, Lieutenant?” Louie had asked. Frémont had been on two surveying expeditions into the western Carolinas and considered himself a woodsman. But no, no buffalo.

“I figured not,” Freniere had said. “Well, you got a treat in store for you, I’ll say that. Buffler is the biggest, fastest, goddamndest animal in the whole world, bar absolutely none. I’ll put it up against elephants in India for wonder and Spanish bull for power—”

“Grizzly is the baddest,” a swarthy man named Martineau had said.

“That’s right, and buffler is the best. He’s like a king, d’ye see, he’s a challenge: it takes a man to ride him down and stop him. ’Course they’re easy enough to kill by creeping up on ’em, but hell, that’s like sleeping with a woman in a bundling bed—it ain’t near the fun it might be.”

“God Almighty, yes,” the heavyset Bladon had said with an explosive laugh. He had a kinky black beard. “I spent a night in one of them years ago. Give me the stone ache for a week.”

“And eating,” Freniere had said, ignoring Bladon, “why you just ain’t et till you’ve had buffler roasted on a prairie fire, a few chips tossed on the coals for seasoning. Fat cow makes beef taste like putty.”

“God’s truth, Lieutenant,” Martineau had said. “Buffler will spoil any other meat in the world for you.”

The office door had opened then and Mr. Nicollet came out. Frémont had reported to him upon arrival the night before. Niccollet was a Frenchman who had come to America eight years before, in 1832, to explore the frontier; he’d been much taken by Frémont’s own French heritage and his command of the language. St. Louis, though American for nearly four decades, still felt itself a French city, and most of the men on the expedition were voyaguers from the old French fur trade on the northern lakes, as accustomed to the canoe as the saddle.

“Gentlemen,” Nicollet had said, smiling, and the men had fallen silent. The astronomer was in his early fifties and his hair was iron gray, though still thick. Frémont thought his eyes looked tired. His manner was gentle and the men had started to call him Papa Joe.

“All’s ready, then,” he’d said in a voice that sounded short of breath. “There’ll be nineteen of us and we’ll draw our livestock at Fort Pierre. The Antelope starts up the Missouri at dawn and every man had better be aboard. You’re free tonight to wind up your business here—just make sure you don’t wind yourselves so tight you miss the boat.”

Louie had winked at Frémont.

“Any of you who haven’t met Mr. Frémont should do so,” Nicollet went on. “John Charles Frémont, Second Lieutenant, Corps of Topographical Engineers, United States Army. As you know, the expedition is under the auspices of the Army, which is reimbursing the American Fur Company for costs. Mr. Frémont is the Army’s official representative. He’ll serve as second-in-command and will assist me in the scientific side of the expedition.

He paused, looking from face to face. “Bear in mind that the whole purpose—the only purpose—of this venture is to map the great stretch of terrain lying between the headwaters of the Missouri and the Mississippi. We’ll take six months, all told: here to Fort Pierre and across to Fort Snelling on the upper Mississippi, and we’ll be back in late October—well, say early November. Now, let me say again that there never has been a map made anywhere in America—or, I venture to say, anywhere in the world—of the quality and the particularity which we will achieve, nor one which employs the scientific methods we will use. So I’m counting on everyone to do whatever may be necessary to make this achievement possible.”

He had nodded to a dour man with searching black eyes. “You know Mr. Provost—he’ll serve as camp conductor and will be responsible for keeping us moving in good order day by day.” Hearing the name, Frémont had glanced quickly at Provost, who returned the look without expression. Etienne Provost was a famous name on the frontier. Frémont judged him to be about Nicollet’s age, but he looked harder. He was a mountain man and he trapped with Jim Bridger and ridden with Jedediah Smith; he had fought at Pierre’s Hole and year by year he’d brought his beaver down to the great rendezvous on the Siskadee.…

“And our friend Louison Freniere,” Nicollet said with a smile, glancing at the man in the glorious buckskins, “has signed on as a hunter and will keep us in meat.”

“We won’t have no food problems, Papa Joe,” one of the men called. “Buffler sees Freniere in his fancy suit and he’ll drop dead of shock.”

Freniere grinned and lifted the rifle he carried. “Never you fear, boys. If the suit don’t get ’em, my old Hawken will.” Made there in St. Louis with an octagonal barrel of soft rolled iron, brass-bound to a cherrywood half-stock, muzzle-loaded and fired with the new-style caps that were putting flintlocks out of business, the Hawken was as fine a rifle as you could buy in the world. It had cost a full forty dollars and all the way from St. Louis across the great northern prairie, Frémont noticed that the hunter watched over it as he might have a woman. Nicollet had instructed Frémont to spend his days with Louie and learn the feel of the land, and Freniere had promised to make him a hunter as well.

Now, as the two horsemen neared the crest of the long, dominating ridge, Freniere’s hand still rested on the Hawken’s well-blued hammer. Since challenging Frémont he had ridden in absorbed silence, his hat pulled low, ignoring the immensity of land around them. He reined up and dismounted, glancing ahead at the glare-struck sky, and dropped a slender rawhide loop over his horse’s head.

“Don’t never pay to top a ridge like you owned it,” he said quietly. “Never know who’s watching beyond. We’ll walk up for a peep and see what we see.”

At the crest he crouched and then flattened and crawled forward. Frémont followed, elbows grinding in white dust, the smell of sun-warmed sage astringent in the air. A stinging gnat lighted on his face and he flicked it away. Louie stopped moving and together they looked down into a vast bowl of open country. It dwindled to blue haze in the distance and in between it was rolling and broken, tawny-colored and gray-green with bunch grass and sage, and there were dark patches on it like timber where timber didn’t belong.

“What’d I tell you?” Freniere said softly. The patches were buffalo grazing, fifty or seventy to a herd, and there must have been fifty herds. He nudged him and jerked his head and Frémont looked to the left. There, just below the crest, much closer than the others, was a herd of nearly a hundred. A huge old bull was in command. The wind was blowing across the animals and no man scent reached them. They were moving slowly to the right, feeding as they went, making a constant grunting noise that Frémont realized he’d been hearing since he first looked. A pair of gray wolves skulked behind them, hungry and disconsolate. The old bull, though unalarmed, was watching the wolves. Frémont realized his hands were trembling slightly.

“Boys’ll be happy tonight,” Louie muttered. They had found no game but antelope and the men were grumbling. They hobbled the two horses they had ridden all morning and took their fresh mounts. Frémont’s runner was a big bay with white stockings, an intelligent, good-natured beast named Barney who worked without complaint. The girth was loose and Frémont cinched it tight, bracing with his knee. He checked the cap on his stubby plains rifle and examined the .50-caliber pistol he carried in his belt.

Louie swung to the left so that they topped the ridge behind the herd and started toward it. Frémont seized a breath. His lungs were not working quite right. The old bull saw them against the sky and threw up his head and bellowed. The herd lurched into a sudden gallop and the bull turned to meet the horsemen, head down, snorting and pawing the ground.

“Hi-yah!” Freniere yelled and his horse leaped away and Barney tilted into a gallop as if he were spring-loaded. The bull was not at all intimidated but when the last of the herd passed him, spreading and moving faster, he turned and followed, bellowing threateningly. The horses separated and Frémont forgot about Louie, for he had fixed on a cow. He gave Barney his head, reins high and spurs hard in his ribs. The cow could hear the horse behind her and she stretched into a dead run, but Barney had fixed on her too, and he was closing the distance.

Thunder filled the air, the horse’s hooves on the hard ground, the herd drumming in full gallop, cows bawling in anger and fear. Dimly Frémont heard the bull’s rumbling bellow and a calf’s piercing squall and his own loud voice. The cow galloped head down, throwing up clots of dirt, and dust clouds blotted out the other animals and stung his eyes. The horse was gaining and Frémont crouched forward, part of its flexing motion, reins in his left hand, rifle in his right, shouting encouragement. Another cow, a calf at her flank, blundered out of the dust on their left and Barney shied to the right as the strange cow reared backwards. Then Barney loosed a new surge of speed and closed with the cow, just behind her right shoulder, just where he belonged.

So close, she was stunning. Frémont had never seen an animal as awesome. Her hump was as high as his waist as he sat his horse. Her shaggy hair was matted, tawny-colored on her forequarters tapering off to black-brown on her rump, winter hair coming off in ragged clumps. Her little horns were polished hooks, her eyes shot with blood, her mouth open, tongue out, streamers of foam whipping behind her.

Staring at the great brute size of her, the horse matching stride for stride, the wind crashing in his ears, his own voice howling and wordless, he knew now what they meant by the sheer joy of the buffalo run. She cut sideways into a small draw, seeking its brushy cover, and Barney turned hard behind her. They crashed through low brush and Frémont heard it cracking under the horse. He felt Barney shift and twist as if he were dancing and he caught a glimpse of hole-pocked ground beneath him, but his mind hardly registered its meaning. The cow glanced over her shoulder, her bloody eyes glaring. Her big head rolled and she hooked a horn at the horse’s chest. In mid-stride Barney sprang sideways. Frémont lurched against the animal’s neck and his left foot lost the stirrup. The rifle slipped and he clutched it frantically against Barney’s wet flank and regained his grip. Cursing, he grabbed the saddle horn with his rein hand and that snapped the horse’s head back and checked him and threw Frémont forward again. He loosed the reins, fumbled his foot back into the stirrup, found his seat and rammed spurs into Barney’s ribs.

They closed again and Frémont dropped the reins and brought the rifle to his shoulder. He half-stood in the stirrups and the horse, confused by the signals, checked again. Before Frémont could fire he was thrown forward and he grabbed up the reins. Sweat ran in his eyes and blinded him, but his hands were full of reins and rifle and in a moment he forgot the burning. The big horse felt him take control and burst forward. The cow hooked at him and canted off in a new direction and Barney cut after her and closed again. Now, holding the reins in his left hand, clasping the horse with his knees, Frémont rested the rifle on his left forearm and fired at the two-foot range. Two hundred grains of powder exploded and drove a slug the size of his thumb into the cow’s side. She grunted but her stride didn’t break. Frémont stared at her. It was like an apparition. He had hit her a killing stroke and she wasn’t going to fall—she wasn’t even going to stop running.

He knew he could never get powder and slug down the muzzle on the gallop—never mind the easy way Freniere had described the trick—and he thrust the rifle into its boot and drew his pistol, thumbing back the hammer.

The pistol was his weapon. He was in good control, reins in his left hand, crowding Barney against the cow, pistol aimed across his left elbow, drawing a killing bead—when the horse dropped out from under him and he pitched forward, flying, falling. He heard Barney grunt as its chest struck the ground, and he threw up his left arm and landed on his face, sliding and rolling. The pistol fired and flew out of his hand. He lay there a moment, ears ringing, eyes closed on darkness, oddly conscious of a bitter yet clean grassy odor, and then he lifted his head and saw his cow disappear in the brilliant sunlight, her stride still unbroken. A half-dozen cows thundered by, hooves pelting his face with dirt, and a young spike bull leaped directly over him, a sudden dark bulk overhead and gone, showing no interest in attacking him.

Then the herd was past and he was conscious of the quiet; he heard hoofbeats drumming down, fading in the distance. Gingerly he moved his arms and shoulders and felt his neck and decided nothing was broken. He was still half-stunned and thought he might vomit. Then he discovered the source of the odor. He had landed in wet buffalo dung; it was in his hair and smeared on his face. He wiped it from around his eyes. Barney struggled to his feet and stood heaving for breath by the grass-filled little gully that had thrown him.

He heard hooves and turned to see Louie riding up with a look of concern. It occurred to Frémont that he was lucky to be alive. He wiped his face. This damned dung was all over him. He had a savage headache, but the ringing in his ears faded and he became aware of a new noise. The hunter was sitting on his horse and laughing out loud. Sudden rage filled him. Missed his cow, fell off his horse like a damned fool—

“Goddamnit!” he said, glaring at Freniere, his fists balling unconsciously. His throat was raw.

Freniere’s smile faded and he took on a wary, thoughtful look. He waited a moment and then said softly, “You been bathing in shit for some reason, Charlie?”

Frémont looked at Louie, and then he began to laugh.

“Life’s little blessings,” he said. “It broke my fall.”

The hunter nodded and his smile returned. “You get a shot off?”

“Might as well have thrown a stone. She took that slug and never slowed down. I couldn’t believe it.” He ran his hands along Barney’s legs. There were tender spots, but not the real pain that would mean broken bones. The horse was streaked with lather. His muscles were quivering. Frémont loosened the saddle and girth and pulled bunches of dry grass and began scrubbing him down, drying him and working his muscles. Barney sighed and gave several little snorts.

“Ran off her ribs, I expect,” Freniere said. “If you don’t hit ’em in the lungs or the spine, you won’t get ’em. It’s funny, the buffler’s so big and that vital spot so small. Did you aim on that spot, like I told you?”

“Aim? I was lucky to get a shot off.”

“Never knew a man to get a buffler first try. I run seven cows before I brought one down.”

Seven? Suddenly Frémont felt good. By God, he had run the buffalo and it was true, there was nothing else like it on Earth. And this land was full of them and he would run another tomorrow and the next day and the next, and damned if it would take him seven runs before he stopped one!

He let Barney graze a few minutes and then he tightened the girth and they rode together to Freniere’s kill. The two wolves were making a cautious approach. Freniere rushed them and they whirled and ran, their brushes tucked. They stopped a little way off, sat on their haunches and watched.

The cow lay on her side, blood still dribbling from her mouth. Gouts of it stained the ground around her. Grunting, Frémont helped Freniere roll her onto her chest, hindquarters cramped beneath her, forelegs spread and cradling her head. She looked as if she were asleep. She was huge. The top of her hump was level with his shoulder even when she was flat.

Freniere drew the long butcher knife he carried in a scabbard at the small of his back and sliced out her tongue with a steady, sawing stroke. Leaning against her rough hair, he made a long incision down her spine and laid the skin to one side like a table to hold his cuts. He began to butcher, explaining as he went along. He took the boss, that little hump on the back of her neck, and then the hump itself and what he called the hump ribs, which Frémont saw was a sort of extended vertebrae that supported the hump. He took the fleece—a rich strand of ungrained flesh between the spine and the ribs that was covered with a three-inch layer of fat. He laid the pieces carefully on the folded skin.

“Oh,” he said, straightening his back, “but this is a fat ’un. That fleece fat there’ll make your face shine with gladness.”

He unhooked a tin cup from his belt, lifted the massive head, rested it on his shoulder and cut the throat. Foaming blood poured out and he thrust the cup into the stream. When it was full he held it up, took a swallow and shoved it at Frémont.

“Drink that, Charlie,” he said. “It’ll make you a true son of the plains.”

Frémont took the cup without hesitation. Of course he would vomit, but better to fail trying than to fail for not trying. On the first swallow he began to gag, but then he realized that it was not so bad. It tasted like warm milk, fresh and very rich. His stomach held and he emptied the cup and handed it to Freniere.

“Not the best drink I’ve ever had,” he said evenly, “but not the worst, either.”

Freniere gazed at him with a look of open delight. “Hiyah!” he whooped, and fetched Frémont an openhanded clap on the shoulder that staggered him. “You’re all right, Charlie! You’re not just a stargazer. You’re going to make a first-class buffler man yet!”

* * *

The camp was in deep shadow when Freniere and the Lieutenant came in. Etienne Provost, crouched on his haunches mending a pack strap, watched Frémont unsaddle the white-socked bay, moving stiffly, favoring his left shoulder. The big horse went down on his knees and rolled, shivering with pleasure, scrubbing his sweaty back while Frémont studied him critically, hands on his hips; his hair and jacket were caked with cowflap. Provost smiled to himself and spat. Took himself a little fall. Well, wouldn’t be the last time.

“That one yours?” He gestured with the buckle toward the great raw carcass bulking on the meat cart, where Boucher and Peters were already at work.

Frémont looked at him—one quick, alert glance, measuring; then he shook his head. “No,” he said simply. “She’s Louie’s. I missed.”

Provost chuckled. “I wouldn’t wonder.”

“—This time.” The Lieutenant held up one forefinger, and again there was that intense flash in his eyes; hot, almost defiant. Didn’t like to miss, then; that was a good sign. Handsome young feller—looked too fine-spun for the wilderness. ’Course you never knew. Have to see how he salted down.

Frémont had the horse up now, and was rubbing him down. Small man, but quick and wiry; stronger than he looked. Nicollet said he was a good learner, accurate with all that stargazing folderol they sat up messing with half the night, but that didn’t prove nothing. Have to see how he did when the coffee and tobacco ran out, and his boots wore through, and the weather turned savage.

“Look as if you been wrassling one,” he said in quiet amusement, and someone over by the fire laughed.

Frémont grinned then. “Yeah,” he murmured. “I got into it with both hands.” He’d finished hobbling the bay, and he walked away quickly toward the little knoll where Nicollet had set up the instrument tent.

“Now don’t you sell Charlie short,” Louie called. “You boys should have seen him take off after that cow—like he by God planned to ride her…”

Several of the men standing around the fire had turned to Freniere, listening.

“I told him wouldn’t be no time to be tucking his butt—”

“That’s for sure,” Peters said, “and then some!”

“Got him a little hot, that did. But I want to tell you, old Charlie didn’t let any grass grow under that horse of his.”

“That so, Louie?” Provost said.

Freniere turned and faced him. “Shining gospel. He took his chances. He missed his cow, sure—but it wasn’t for lack of trying.”

Provost grunted, and ran his eyes over the camp. The spring-fed stream winding down a fissure in the prairie was small enough to step across in places but above, where he’d sited the main camp, it had widened into a shallow pool. The small bar oaks and ashes growing beside it had a stunted look. Later in the year it would be bone dry. The carts were disposed in a rough half-circle beside the pool, their shafts atrail; only a few had been unloaded. Boucher had hung an iron pot from a tripod over the fire and was fixing racks of buffalo ribs on sticks. The dry wood burned with little smoke and collapsed into ruddy coals; Martineau judiciously added buffalo chips to flavor the meat.

Provost sighed, set the strap aside and settled back into his saddle pads. He’d already posted guards: Terrien was with the horses, and he could see Menard above the camp, scanning the horizon for movement against the light. The Yankton Sioux were friendly, but with Indians you couldn’t never be sure; not with good horses in camp and night coming on. Peters was bringing wood for the fire, and on the flat below Dixon, the expedition’s guide, was working on a horse that had gone lame, cradling the hoof on his knee, digging at something jammed in that tender place between frog and buttress, while Zindel held the animal’s head. Sour, silent old Bill Dixon, keeping busy, trying not to think about Mr. John Barleycorn.…

Well, every soul had its demon, as Papa Joe said. Provost studied the knoll again; Nicollet was seated on a box writing in his journal, using the tailgate of the equipment cart as a desk; Frémont was standing beside him talking, one foot cocked on the spoke of a wheel. A movement on the rim of the hill behind Frémont caught his eye then—a wolf that ducked instantly from sight. Provost chuckled. Empty. He’d heard a fancy Virginia gentleman once. “I say, nothing but barren, lifeless spaces. Everywhere you look.” Damn fool—the whole land was humming with life! A million creeping, gliding, soaring things. But you had to know how to look, that was all …

“Aaaiii, festin!” Boucher sang from the big fire. “Come on in now!”—and there was a quick movement toward him from all points. A pale sliver of moon had appeared in the eastern sky; the west was still bright. The odor of cooking meat was overpowering. Martineau was cracking bones with a small ax and thumbing out rolls of marrow—trapper’s butter—which Boucher kept stirring into the iron pot. The soup bubbled viscously, marrow and molten fat and blood from the butchering, bound with pepper, its aroma swirling on the light wind.

“If it tastes as good as it smells,” Frémont said, “we’re in for one hell of a treat.”

“Tastes better than that, Charlie!” Freniere told him, and Boucher laughed.

All of them were around the fire now, throwing down their apishamores for couches, gazing at the racks of roasting meat, their eyes glinting; there was an air of contained excitement, like men gathering in a tavern. The meat crackled richly, and droplets of fat made tiny yellow flares i

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...