ONE

It hadn’t hurt, the day he had cut out his own heart.

Andrew had written about it later in spidery lines from a sharp pen—a story about a boy who took a knife to his chest and carved himself open, showing ribs like mossy tree roots, his heart a bruised and wretched thing beneath. No one would want a heart like his. But he’d still cut it out and given it away.

Being left aching and hollow was a familiar feeling. A comfortable pain.

Andrew had always been an empty boy.

It was easier to tell a story than say how he felt, so he’d ripped the page from his notebook and slipped it into Thomas’s back pocket the day school let out for the summer. Then Andrew had dissolved into his father’s car and Thomas had been swallowed by the bus, and that had been it. They would be severed until Wickwood Academy opened again.

It didn’t matter if Thomas read the truth in the story or not, how he alone owned Andrew’s heart. The thrill of the confession had been terrible and beautiful—and retractable. Just in case.

There were words for people like Andrew Perrault. Desperate, maybe. Awkward fit, too. Coward stung, but it wasn’t a lie.

Andrew was probably the only person who didn’t crave summer or holidays, but he felt better at school, solid and more real. He’d boarded at Wickwood since he was twelve, and the ivy-smothered walls, the old stone manors, even the rose gardens and forests cloaking the campus, all felt like home. He left everything here—his books, his memories, his school things. He left Thomas Rye here, too.

Andrew was hungry for it. Take him away and he starved.

But summer had ended, and that feeling of wholeness hadn’t yet filled his chest as his father drove him back to Wickwood. All he could think about was how this was their final year. Dread already threatened to suffocate him.

Andrew pressed his cheek to the cool window glass as the BMW snaked along winding roads. The forest grew so thick on each side it felt like gliding through a tunnel of dark and wolfish green. It should take an hour to get there from the city, but his father had been driving at a glacial pace. Usually he moved with confident speed, taking calls and dictating emails to his phone, his grip easy on the wheel as his gold watch clinked against matching cuff links.

Today Andrew’s father sat rigid, a muscle in his jaw flexing. He kept glancing at Andrew through the rearview mirror, and Andrew kept pretending not to notice. He stuffed in one earbud against the silence. His notebook lay open on his lap, two lines of a new story begun.

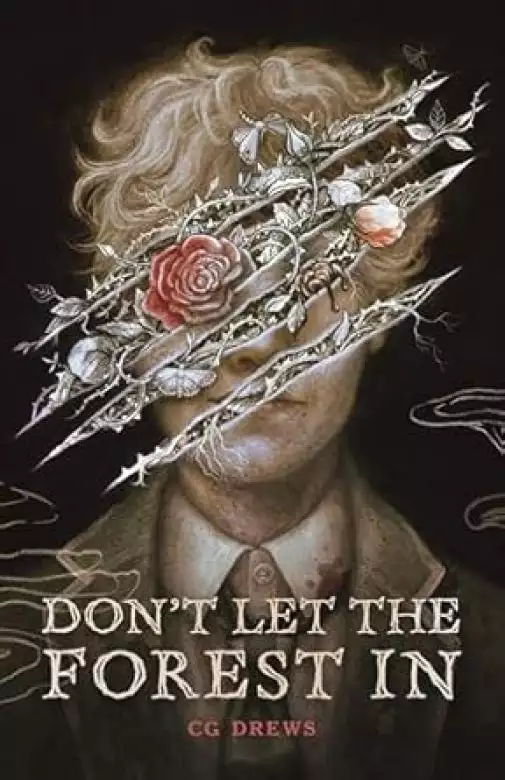

This was what Andrew did—told stories. Ones with dark, bitter corners and magic curled into thorns. Ones about monsters with elegant, razor-like teeth. He wrote fairy tales, but cruel.

Thomas loved them.

Once upon a time there lived a prince who wore a crown of rowan to protect him from woe, but a sweet willow maiden asked him to take it off in return for a kiss. After the kiss, she cut out his eyes.

They’re the best, Thomas said. They make me want to draw. Do they mean anything?

Andrew had given a small shrug, but a fever lit beneath his skin at the praise. They’re just meant to hurt.

Like a paper cut—a tiny sting that meant nothing more than I’m alive I’m alive I’m alive.

Thomas was the only one who understood the stories. Andrew’s father didn’t. Even Dove didn’t, which felt like a betrayal since they were twins.

She sat in the front passenger seat of the BMW, her arms folded and her posture stiff. She was locked in a frosty war of silence with their father. Over what, Andrew had no idea, but they wouldn’t even acknowledge each other.

They looked like twins, Andrew and Dove. Pale skin, honey-gold hair, brown eyes, and not much height difference between them. But Dove was a statue of glittering ice, beautiful and dangerous and impossible to reshape, while Andrew was more like a collection of skeleton leaves, fragile and crumbling. Dove was the one everyone saw, and Andrew was the one they forgot.

She wore the Wickwood uniform of white collared shirt and tie, deep green blazer and plaid skirt, not a single button or wisp of hair out of place. Dove had the graceful poise of someone expecting to stand before an auditorium and give a valedictorian speech while cameras flashed, immortalizing her as an example of perfection. She’d be fine this senior year; she’d own it. Andrew suspected this year would beat him up in a back alley and leave him for dead.

Already his stomach felt knotted, but he told himself he’d calm down when they arrived. Thomas would be waiting with his freckled cheekbones and troublesome scowl, forever angry at everyone except the Perrault twins.

He was theirs, and they his. The three of them had been this way since they met.

The car’s tires rolled from smooth road to crunching gravel, and Andrew pressed even closer to the window. His heartbeat sped up. Here was Wickwood, grown from the forests and thorns of middle-of-nowhere Virginia. Cars and buses filled the circular driveway, and students flooded the marble front stairs alongside baggage and fretting parents.

As their car crawled forward, looking for a place to park, Andrew searched for Thomas. Nothing.

He glanced at his phone. His heart still gave a small jolt at the sight of the scars crisscrossing his skin, thin as cobwebs, from fingers to wrist. It didn’t hurt anymore. He barely remembered how they had happened.

He checked for texts, knowing there’d be none since Thomas had broken his phone a week into summer vacation.

Andrew pulled up their last exchange and chewed his lip.

phones pretty muvh smaashes exicse typos ill see you when schools back

Andrew had taken an excruciatingly long time to think up a reply that didn’t sound panicked. An entire summer. No talking. Thomas could email, except he never did.

Andrew had texted: How did you break it this time??

well dad did. hit my heead wth it then thrw it at wall. Its abot to die cabt charge. don’t freak out.

How the hell was Andrew meant to not freak out? It wasn’t the first time Thomas had offhandedly mentioned something like this happening—though it seemed the violence was shocking to Andrew alone—but he couldn’t stop thinking of how much it would have hurt. Or if Thomas’s father had concussed him with a blow like that. Or about the long weeks where worse things could happen to a boy with a sour mouth who never knew when to stop.

Thomas had that in common with Dove—you’d have better luck softening stone.

Andrew’s father pulled up behind an unloading bus and left the engine running. The chaos of hundreds of voices thrummed against the window. Andrew hesitated, fingers on the door handle. As intense as it was out there, it would be better than the strangling tension in here.

“Andrew.” His father studied his hands as if they’d been welded to the steering wheel. “There are other schools.”

Andrew shoved open his door.

“Andrew.”

The sigh was frustrated, but also tired, and it made Andrew slump back into his seat and let the car door thump shut. They’d had fractured variations of this conversation before and he hated it. Last year had been … It didn’t matter. It was over.

Andrew wasn’t changing schools. His life was here.

He looked out the window again for Thomas.

“Fine, then listen.” The muscle in his father’s jaw flexed again. “If it’s too much, call me and I’ll come. We can transfer you somewhere else, anywhere you want. And talk to the school counselor if you … Just talk to her.”

Andrew checked to see if Dove was steaming that their father was leaving her out of the conversation, but she must have slipped out while he’d been distracted. Great. No reconciliations were happening today.

“Are you coming in?” Andrew said.

His father’s voice was tight. “I have a flight to catch.”

Andrew didn’t ask where to, and his father didn’t say. He was an international land investor and developer, owner of hotel chains and restaurants, with enough charm to convince anyone to do anything. Sell, buy, invest. It was the Australian accent, Dove had said, and added, Look, Andrew, we’re still novelties in America. Lean into your accent and you’ll have any girl by the end of high school.

Andrew decided to speak as little as possible for the rest of forever.

Invisible was best. It was easier to speak less and hide his softest parts so he could fit between the shadows of the rich private school kids with their bored expressions and catlike claws. They took down prey for fun and only left it alone once it knew to stay on its belly. He understood the rules.

“Just don’t go into the forest,” his father said. “Andrew? Promise me that at least.”

“Okay,” Andrew said, but he couldn’t mean it since the forest was Thomas’s favorite place.

This time when Andrew got out of the car, his father didn’t stop him.

Andrew set his suitcase on the footpath and propped his satchel against it. Dove hadn’t waited. That hurt. He jammed his notebook into his suitcase and fought the zipper as his father’s car pulled away.

Then it was just Andrew alone, with sweaty hands and a firm pulse of anxiety in his stomach. By this point, Thomas should have seen him and descended. The three of them would usually crowd together on the steps, an instant hurricane as they caught up. Thomas would sling his arm around Andrew’s neck while he teased Dove for already starting to outline their plans for extracurriculars this year.

Friends, best together. They were everything they needed from each other, and it was enough. It had been that way since they enrolled at Wickwood.

Andrew repeated that a few times so it felt solid.

But what if Thomas wasn’t here? What if his grades hadn’t secured his place or if his parents had pulled him from Wickwood or murdered him—

A scuffle from the stairs made Andrew turn. Everything was stone out here, boxed in by manicured lawns and late summer roses, and it carried the air of comfortable tradition. Except instead of gentleman scholars, Wickwood had its fair share of spiteful vultures ready to pick the bones of the weak. A pack of seniors messed around on the stairs, their backslaps and howls of greeting drowning everyone else out. But it was the smack of a hand against a book, the ensuing explosion of pages, and a vicious yell that caught Andrew’s attention.

Thomas stood with fists bunched, one hand gripping the railing like he meant to pound up the stairs. His sketchbook looked like a bird shot from the sky, pages flittering around his feet.

The vultures would claim it had been an accident. They’d be believed because they were Wickwood’s finest. Well-bred and rich, white teeth and perfect hair, their family names moneyed and sleek and attached to politicians and lawyers and CEOs.

Whereas Thomas fit none of those criteria, and he didn’t have the sense not to hit someone and be expelled before first period.

Andrew cupped his hands around his mouth. “THOMAS.”

Dozens of heads turned.

Only one mattered.

Thomas’s whole body tilted toward the sound, as if even amid the crush, his name from Andrew’s lips would always be heard. He shot one last furious look at the vultures and then burrowed through the masses to arrive breathless at Andrew’s side.

A second stretched between them, long enough for Andrew’s anxiety to beat like moths behind his ribs. Everything had gone wrong already with Dove vanished and Thomas late. After all, friendship lasted forever until it didn’t. Months apart could change someone. Stretch bonds. Break them—

“Are you okay?” Thomas said.

Andrew hesitated before nodding, because this wasn’t their normal greeting. But then Thomas launched into him, and the way he crushed his arms around Andrew’s shoulders said everything.

It only lasted a second. Then Thomas pushed away and thumped Andrew’s shoulder, his smile a blazing star. “There’s nothing of you. Didn’t you eat this summer?”

“Isn’t that what grandmas say?” Andrew let a wry smile play on his lips, and it didn’t fade when Thomas shoved him.

“It’s what people who are hungry and projecting say. I’m starving.” He snatched for Andrew’s satchel and hooked it over his shoulder. “Can’t believe they don’t feed us breakfast first day back. Come on, we’ll dump your stuff before assembly starts. How was summer? Hell?”

“Always. How was…” Andrew hesitated, doing a precautionary sweep over Thomas. To be sure he was whole.

To be sure he was real.

Everything looked the same—auburn hair and sharp jaw and face like someone had upturned a whole jar of freckles on him. He was at least a head shorter than most boys his age, and he wore his uniform like he’d been in a fight—white shirt scrubby and untucked, tie a mangled noose at his throat. No blazer. No vest. Ink-stained fingers and paint smudged under his jawline—

No, not paint, a scab. Andrew resisted the urge to reach out and rest his thumb over the shape of it.

“I, for one,” Thomas said, “want to punch Bryce Kane and his crew, but that’s not new.”

“Was that sketchbook—”

“Not much in it. Forget about it.” Thomas scooped a page off the ground and stuffed it into his pocket. “Do you need anything? Do you need me to … I don’t know. I just—” He scrubbed at his hair and tilted his head toward Andrew.

He shouldn’t be fussing like this. He hadn’t even asked why Dove was in a mood or why they’d arrived late. He hadn’t even launched into a proper rant about Bryce Kane and his vultures, Thomas’s personal nemeses, who he antagonized as much as he got picked on. Instead he seemed jittery, as if he’d had too many coffees and couldn’t quite keep eye contact.

Copyright © 2024 by CG Drews. Copyright © 2024 by Jana Heidersdorf.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved