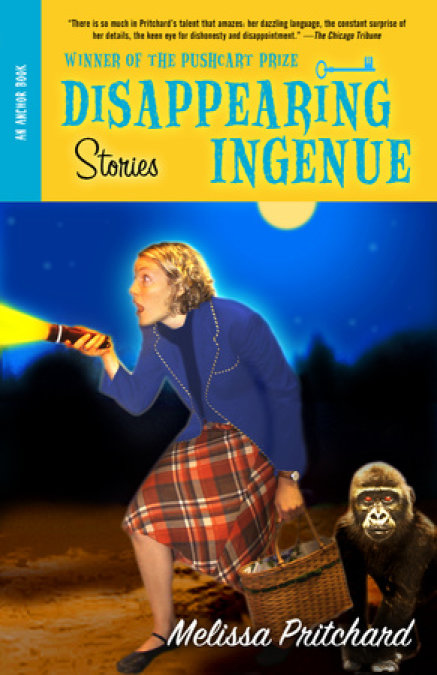

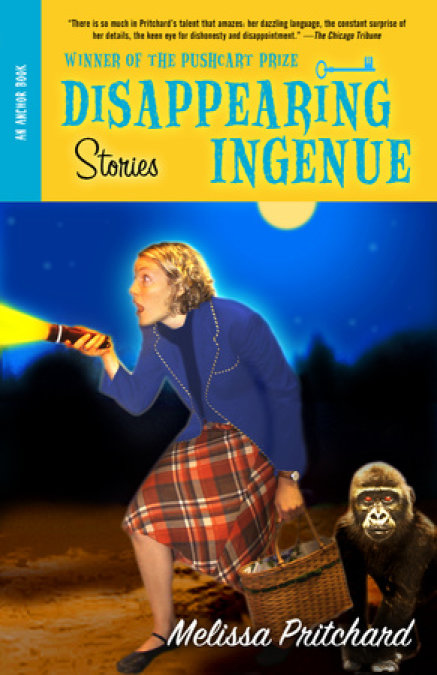

Disappearing Ingenue

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

This wildly imaginative collection presents the misadventures of unlikely heroine Eleanor Stoddard as she tries to lead an exemplary life but finds that things just keep going awry. In the summer after sixth grade, she dreams of being as courageous as Anne Frank. As a teenager, her sudden devotion to Catholicism coincides with her crush on a nun. As a suburban housewife who suspects her husband of having an affair, she imitates Nancy Drew to try to solve her own personal mystery. And as a middle-aged woman, she embarks on a trek through Central America accompanied by a rescued laboratory gorilla. While Eleanor makes her way through a whirlwind of adventures with life and love in which she is constantly reinventing her identity and rethinking her priorities, she manages to become a first-rate student, a published poet, and a loyal mother. Each story offers a glimpse into her familiar and charmingly odd journey, and she comes hilariously to life in these disarming tales.

Release date: June 10, 2003

Publisher: Anchor

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Disappearing Ingenue

Melissa Pritchard

"My, I'm glad you came, Nancy!" Bess exclaimed. "George has been frightfully worried that something might have happened to you."

"To me! What an idea!" Nancy laughed it off.

"I worry every minute that you'll get into real danger,"George confessed.

"Why, I've been so good lately, it hurts," Nancy replied.

--from The Clue of the Velvet Mask: A Nancy Drew Mystery by Carolyn Keene

Eleanor Luther, once known to her Isabella Street neighbors as "Kit" (for "Kitten"), and to the various small children of Isabella and Thayer Streets as "Moo" or "Mooser," happened, while dusting her husband's nightstand, upon a terrible clue. Like the miniature key given by Bluebeard to his newest and most naive wife--My palace is yours, dearest, but for one small door"--Eleanor plonked down on the just-stripped bed to read lyrics dashed out in Neil's spidery, introverted hand:

Your smile is like sunlight

Your love is all mine

Your eyes blue magic

Your blonde hair divine …

Oh fudge, thought Eleanor. Oh rot. She tried to squeeze herself, like a long, ugly foot, into the glass slipper of those soppy lyrics, but catching her woesome reflection in the full-length mirror, conceded not, surely not. Neil’s other symptoms--the custom-made Italian suit, his morning isometrics, Friday's rock 'n' roll night (when she was deliberately kept in the dark as to his whereabouts until he returned at 2 A.M.), the sexual lethargy governing their bed--these could be overlooked, excuses could be made, but wasn't a love song evidence hard and undismissable as a rock? Eleanor jabbed the note back into the paperback book it had dropped out of (The Milagro Beanfield War), and resumed cleaning, switching on the vacuum that had once belonged to Neil's grandmother, heavy as a torpedo, roaring like hell's oven, and, for all its sound and fury, picking up very little. Neil's miserly streak was another of the many things they argued over subliminally. As a housekeeper, Eleanor balked and no doubt this was why--you risked uncovering something. If Neil was having an affair, why ever should she know?

Eleanor Stoddard met Neil Luther eight years before, when she was a Congregational minister's secretary, and he had loped into the church office to ask directions. She had never met anyone so handsome (people regularly mistook him for Clint Eastwood), so reckless, so physically impulsive. Eleanor judged herself ordinary as salt, too methodical, which of course drew her to men who were passionate, men unafraid of being boys. When their first date consisted of sitting beside the closed casket of a stranger in a third-rate Chicago funeral home, sole mourners besides a blue marlin, preserved and mounted on the wall behind them, when they first lay in her bed together and he whispered, "You look weird in the dark," Eleanor understood she had met the father of her future children. Child.

Little Marylou, six, was on schedule with other little girls in the tidy curriculum of a Midwestern suburb. Tumbling, gymnastics, ice-skating, ballet, and this week, Eleanor would begin chauffeuring her daughter to horse stables in nearby Morton Grove. Gymnastics daunted Eleanor, ice-skating vexed her, she disliked being huddled near the ice with the rest of the mothers in their mauve and teal parkas, inert as pillows. And ballet, with its potbellied, insect-legged girls, wobbling and starved, made Eleanor so restless, she wound up auditioning for the Wilmette Community Theater's next play, Picnic, landing Kim Novak's part, Madge, playing opposite a college dropout named Buzz Needles, who told long, filthy jokes and looked nothing like William Holden. On opening night, Neil's whole family (large, Catholic and boistrous) turned out, and her parents shipped a lei from Hawaii made of anthuriums, red, waxy, heart-shaped flowers with mortifyingly erect, bright yellow stamens that gave Buzz grist for a hundred terrible jokes. Eleanor's three brothers-in-law complimented her (the youngest, who drew her name for Christmas several weeks later, would give her a highly suggestive peignoir set), but then the play was--poof!--over, with Eleanor tucked back in her house, gaining weight, or else driving Marylou around in the ancient Mercedes Neil had brought home on New Year's Eve. She and Marylou had been down with Chinese flu, so Neil had a friend drive him to the Polish section of Chicago, where he paid cash for something he admitted to buying, literally, and in a state of intoxication, in the dark. It had a butterscotch leather interior, a sunroof that leaked, and a hole in the floorboard the perfect size and shape of a meatloaf pan. The car stalled regularly, floating like a broken toy over to various curbs, but Eleanor noticed that when she drove it, male drivers tended to ogle and wink at her. When she drove their old station wagon, Blue Buster, no one ogled, no one winked. They were too busy getting out of the way.

The time would come when Eleanor Luther would speculate on the fateful coincidence of reading Nancy Drew mysteries aloud to Marylou that winter. In the wake of her encounter with Richard Bailey, it would seem as if events were not random, things in life were paired, like binary elements, and when a third element was introduced, combustion, followed by an incendiary fate, was altogether possible. Marylou and horses. Eleanor and Nancy Drew. Neil and Eleanor. Neil and his big blond secret. Eleanor and Richard Bailey. Richard Bailey and the murdered heiress to the Brach candy fortune. Poor Helen Brach. Like Madge in Picnic, or herself on Isabella Street, yet another ingenue, but with oodles, scads, electrifying heaps of money. If ingenues tended to gravitate to nefarious or otherwise exciting persons, then a wealthy (and aging) ingenue would surely be a magnet for villains.

If A (Helen Brach) equals B (villain magnet), and

B (magnet) equals C (R. Bailey), then

A (Brach) equals (murdered by villain, Bailey).

It was, in Eleanor’s mind, a lopsided but still dazzling, syllogism.

Eleanor and her neighbor, Audrey Stanhope, had signed their daughters up for equitation class. Basic schooling. With the other mothers, they perched on metal bleachers in the indoor arena, watching their little darlings in black helmets, black boots, white shirts and tan breeches, rumps like underripe apricots bouncing against the saddles, backs straight as xylophones, riding crops in hand. There seemed to be a lot of sitting atop standing animals, waiting for what, Eleanor couldn’t say, but the children looked dear, like stick figures atop great lagging beasts, brutes misshapen and sickle-backed, with dropped bellies, knobby hocks and short necks, kennel dogs with long legs, hammerheads, pony mongrels. That first day, Eleanor found herself watching a short man in old-fashioned jodphurs, standing by the door leading to the barns and arguing with one of the foreign stable hands. A plump woman sitting directly behind Eleanor spoke.

"That’s Richard Bailey. The owner."

For some reason, Eleanor thought of cantankerous George Bailey in her second-favorite movie, It's a Wonderful Life.

"He’s a doozy." The woman said this with such venom Eleanor was instantly alert, but Audrey was poking her in the ribs.

"Kit, look. Sara just got her horse to back up. It'll be Marylou's turn next."

While their daughters were taught to ride huntseat, to command great splay-footed slunkers named Daisy or Smokey, Mohawk or Lotso Dots, Audrey and Eleanor complained about their lives like pastimes gone wrong, drank bitter coffee, kept to their seats with the other mothers, perched like plain wrens, settling for the hour of lesson, then rising and scattering. When Sara, one blustery March afternoon, wrenched her ankle in the Luthers' unthawed yard, sprawling over one of the little red-and-white horse jumps Neil had made for the girls; when Sara fell as Marylou shot past triumphant on her imaginary steed, Neil telephoned Audrey while Eleanor ministered to both shrieking girls. The upshot was Sara, on crutches, dropping out of equitation and Eleanor chauffeuring her daughter in Neil’s old, failing Mercedes, Eleanor sitting off by herself, bored.

Set on the edge of one of the county's forest preserves, Country Club Stables was a humid, shoddy warren of dark barns, full of Dickensian passageways. Neil's parents disapproved of these newest lessons, injury being one factor, not to mention the dangerous moral atmosphere brought on by too many foreign grooms. (Neil's mother, Pearl, harped so much on the "low, criminal element" lurking about in stables, somehow equating foreign with criminal, Eleanor began to wonder if there wasn’t some failed xenophobic romance in Pearl’s life.) But after ice-skating, after ballet (masochism euphemized as "grace"), Eleanor felt intoxicated, hot with pleasure. Horses were erotic, the clichés were true, the snide little jokes. To see men enslaved to horses was sexy enough, but seeing them reduced to grooming and caring for something besides themselves was sexier still. So, during one of the lessons, Eleanor ventured off to explore, which is how she bumped into Mr. Bailey in his standard mustard-colored breeches and tweed jacket the color of spoiled mushrooms. His hair was thick, wavy and silver, his eyes were a plum black, and he looked so disconcertingly like Scarlett’s father, Mr. O'Hara, in her third-favorite movie, Gone With the Wind. Eleanor felt herself recoiling and drawing near at the same time. They exchanged a few words, his brusque, hers apologetic; later, she would realize he had sized her up with a sociopath's cold accuracy.

Sitting back in the bleachers, chomping away at a Baby Ruth, was the same heavyset woman, with the unlikely name of Ariel. "Remember the Helen Brach murder case last year?"

Eleanor remembered. She nodded.

"Richard Bailey was dating her when it happened. Remember how they never found the body? A lot of people believe it's buried in these stables, but there’s not enough evidence to arrest him. The police are just waiting for him to slip up."

"Heels down, Portia." Ariel half stood up to yell at her daughter, then wheezed down, out of breath and smiling brightly at Eleanor.

"He sells bad racehorses to rich women. But Mrs. Brach was an animal rights activist. My theory is she had the goods on him and was about to blow the whistle."

A murderer! thought Eleanor, alarmed and enchanted.

(Oh Mr., Mr. Johnny Lebec, how could you be so mean?

We told you you’d be sorry for inventing that machine.

Now all the neighbors’'cats and dogs will never more be seen,

They've all been ground to sausages in Johnny Lebec’s machine!)

If she turned out the light in their upstairs bedroom, Eleanor could see Neil out in the alley, wearing his old carpenter's suit, an aluminum work lamp clamped to the stockade fence, working on Blue Buster. He was repainting it, which seemed to call for a grinding wheel--her station wagon now bore huge, leprous patches, scabs, up and down its sides. Over a month ago, Neil guesstimated it would be a two-week project. Now she saw sparks flying and worried, was he wearing his Plexiglas goggles? How could he possibly enjoy grinding away at metal instead of being up here with her? It had become the single mystery of her marriage, the way in which Neil's wild streak had been rerouted into a seemingly endless list of domestic projects, most of which narrowly skirted disaster. On her way down to the kitchen to find some chocolate, Eleanor ticked off the worst:

-the time Neil decided to stucco rather than rewallpaper their tiny upstairs bathroom, troweling so much gunk, like vanilla frosting, onto the chicken-wire frame covering the walls that his father, Bert, who stopped by, told Eleanor that weight would never hold, and if Neil wasn't careful--this was no goddamned birthday cake!--the whole bathroom would kerplunk down into the dining room.

-last Thanksgiving, when Neil polished his grandmother's silverware on the stone grinding wheel in the basement, how his mother, setting the table, said, "What in pete’s sake happened to Gigi's silver, this knife's a razor?" and Eleanor was forced to explain how in putting a gleam on his grandmother’s silver, Neil had accidentally ground half of it away.

-last summer's Plaster Party, when Neil promised free beer and pizza to all his friends and neighbors who would drop by to help him restucco the bottom half of their house, how the wheelbarrows were churning with fresh-mixed plaster when a guy from Peru named Pato, who somebody had brought along, started screaming because the lime in the mixture was eating away his hands...how Eleanor had had to run to the hardware store and charge twenty pairs of Rubbermaid gloves.

-oh, and right after Marylou was born, how Neil insisted on saving money by using cloth diapers and washing them himself...then had to wear a gas mask because he’d let them soak in the plastic hamper too long. Neil's projects called for tools that ground things away, for dangerous chemicals, explosives. What would a psychiatrist make of her husband's compulsion to grind to nothing, blow to smithereens, take down the house?

In the kitchen, Eleanor rustled through the pink bag of Brach's milk chocolate peanut clusters. That morning she had stood before the candy shelf at Dominick's, studying three rows of Brach's candies, distributed from a factory in Cicero, Illinois. Wasn’t Cicero an old Roman orator, someone who had been assasinated? What if Bailey had disposed of her body at the candy factory, bits of Helen in the vats...(Oh Mr., Mr. Johnny Lebec how could you...)? Eleanor dumped the peanut clusters into the sink, running hot water over them so she could not be tempted to dig through the trash; she knew her own shameless cravings.

Near the back door was the latest stack of Nancy Drew mysteries from the library, long overdue. She carried several upstairs, along with the gray notepad she made lists on. Whenever she had insomnia, lists helped, were soporific. Ordinarily such sleep-inducing lists consisted of chores, obligations, things to remember, variations of short-and long-range goals. These were not dramatic lists, more like lullabies, sleeping potions. But tonight's list kept her unnerved, awake with perverse comparisons:

NANCY DREW

"young, amateur detective"

"attractive, titian-haired detective"

"pretty, titian-haired detective"

ELEANOR LUTHER

mother of Marylou; wife of Neil Luther

*************

CARSON DREW

"the leading attorney in River Heights"

"tall, handsome...he and Nancy helped

each other with cases and were close

companions"

MORRIS STODDARD

Eleanor's father, a retired orthodontist

who liked to refer to Eleanor as a "kook"

*************

HANNAH GRUEN

"kindly housekeeper"

"a lovable woman who had lived with

Nancy and her father since the death

of Mrs. Drew when Nancy was only

three"

OLD MRS. FISK

cranky widow, met in supermarket

*************

NED NICKERSON

"Nancy’s special friend, a friend of long

standing, a good-looking young man,

broad shouldered and deeply tanned,

a football player...they enjoyed the

same things and frequently went together

to parties...though she had many other

admirers, Nancy admitted that Ned

was her favorite"

NEIL LUTHER

This Christmas, gave Eleanor a frying pan

and a high-necked flannel nightgown

*************

BESS MARVIN

"a pretty, plump blonde, less inclined

to adventure than George or Nancy"

ARIEL

large, nosy woman

**************

GEORGE FAYE

"an attractive, tomboyish girl with short dark hair"

"a dark, athletic girl, Bess' cousin"

"spunky and proud of having a boy's name"

AUDREY

best friend, not related

*************

NANCY'S SPORTY RED COUPE

"given to her by her father, Carson Drew,

leading attorney, etc."

ELEANOR’S BLUE BUSTER

purchased by Neil from a foul-tempered,

one-legged man

Instead of sleuthing, didn't she just plod behind Neil and Marylou, picking up pieces, hardly solving a thing? She was a bit of domestic equipment, an Osterizer, a toaster, old Gigi's vacuum, serviceable and sturdy, a clothespin kept going by the notion she was irreplaceable, special. But was she? Whoever heard of Nancy Drew's mother? Who cared? She died when Nancy was three--every girl’s wish, father to herself, a harmless old housekeeper to do the dirty work--oh, mightn’t Eleanor’s own life have been a different story?

Perhaps I've stumbled on a clue! Nancy thought excitedly.

--from The Clue Through the Crumbling Wall by CAROLYN KEENE

The next morning, as she stood on a chair, hanging cardboard shamrocks in the bay window of their kitchen alcove, as she taped cutouts of leaping leprechauns and pots of gold to the porch windows, Eleanor was forcibly struck by an idea. What if she changed from frump-o housewife to pert, snappy Nancy Drew, smoking out the evil Mr. Bailey, and solving the murder of the candy heiress? With a leftover leprechaun facedown in her lap, Eleanor sat in the living room, watching the videotape Neil had made to send to her parents in Hawaii--a tour of their newly remodeled kitchen and master bedroom. Eleanor was narrating, somewhat like a First Lady tour of the White House, except that Eleanor appeared stiff and wooden. She looked like a bit of housewife-fruit caught in aspic. That was it. She would trap Mr. Bailey, be his Venus-flytrap. Hadn't she recently triumphed, proved credible, as eighteen-year-old Madge in Picnic?

So when Neil left for a three-day board of directors' meeting in Florida, she rented a titian-colored pageboy wig at the costume shop on Central Street and took to wearing the bustier from Picnic under her new, red sweater. Like anyone with a secret existence (her husband for instance), she felt buoyant, revitalized.

"Do be careful, my dear. You always start out solving mysteries with the idea you’ll be perfectly safe and you always end up getting into hot water."

Hannah Gruen, --from The Crooked Bannister by Carolyn Keene

So easy! To lie! Exhilarating! To take drama off the stage and into one's own life! With Marylou in the arena riding a sway-bellied Appaloosa called Lotso Dots, Eleanor glided, in new, patent leather boots, to the door next to the soda pop machine, the one that said "Richard Bailey, Barn Owner and Manager." She knocked, entered the shoebox office, swiveling her hips in a Kim Novak kind of way, until Mr. Bailey was on his feet, behind his cluttered desk, offering his villain's hand to her. Eleanor lowered her voice, made it husky.

"Yes, I should like to purchase one of your instruction horses. My name is Eleanor Drew."

He sat down, leaned back, twirled a pencil. "Which one?"

"Lotso Dots."

"Do you have private facilities, Mrs. Drew? Your own facilities?"

"Ms. Drew. I'm a widow. I’m having a barn built along with a new home up in Lake Forest. In the interim, I assume the horse could remain here."

She had never paired deceit with fun! Offstage, which was most of her life, of course, Eleanor had always been excruciatingly earnest. He believed her!

"I'm afraid I cannot sell that particular horse."

"Why ever not?"

"The animal is unsound. It is only used for children's lessons."

Eleanor kept silent. She wished for a cigarette. For a cigarette holder to hold the cigarette.

"I do have other horses for sale."

"Well, my daughter has her heart set. You know how children are. Arbitrary."

"What are you doing tonight, Ms. Drew? Eleanor."

Her tissue of lies thus woven, Eleanor exited, having accepted a dinner date with the suspected slayer of Helen Brach. Marylou could sleep over at Audrey's, though Eleanor would have to lie about her own whereabouts. Fib to Neil, too, when he called, as he did at eleven o'clock, as if punctuality equaled fidelity. Hah.

But Sara had been dropped off at her grandparents' in Palatine, so that Audrey could sleep with her estranged husband, Sara's father. This was a complicated story Eleanor had heard about numerous times but could never keep straight. Sometimes she pictured herself raising the roofs off all the houses up and down her desperately tidy block, peering down like a giantess at all the square little scenes of pandemonium, room after room of high-pitched squalor. Eleanor wound up calling old Mrs. Fisk, the balding, shadow version of capable, kindly Hannah Gruen. When she was a girl, Eleanor had longed for a housekeeper to replace her mother. She longed for one now. It seemed the penultimate luxury, although the one time Neil had treated her to a cleaning woman, Eleanor found herself tidying up before the woman arrived, then tagging behind her, then fixing them both a substantial lunch so she could hear more of this woman's life story, which, if true, was unbelievable, then having to clean the house a second time before Neil got home to complain he'd been robbed.

Yes, old Mrs. Fisk was available. So Eleanor rented National Velvet and Brigadoon, and with a slick frosting of Nair on her upper lip, fixed Marylou's favorite supper, pigs in blankets. She began to see how guilt disguised itself as solicitude. There she was, a married woman, a mother, impersonating a wealthy widow, meeting a murderer for cocktails. Reasons for this had become ephemeral, slippery as eels. Because she wanted to crime solve? Punish Neil? Have an adventure? No. She shouldn't do this. This was going too far.

Too late. Mrs. Fisk was on the couch, knitting a hideous orange-and-brown checkered afghan while Marylou pranced a platoon of My Little Ponies, Sea Splash, Moonshadow, Princess and Glory, up, down and between her sitter's trousered legs.

"Here's the number where I'll be, Mrs. Fisk. Marylou's bedtime is eight o'clock, and she has permission to sleep in her My Little Pony tent tonight."

Mrs. Fisk sat there, Sea Splash perched on top of her wispy, waspy head. There was something amiss with the woman; what a last resort she was. Eleanor had long ago dropped out of the neighborhood babysitting coop. Too depressing, poking about other people's homes, snooping, which is what she always succumbed to, raw snooping.

She arrived at Hackney's, what Audrey called a hangout for the horsey set. She stood in the small dark lobby until her eyes adjusted, until she saw Mr. Bailey waving her over--he had his own table! He stood up, shook her hand, and she took note of his gold eyetooth. Out of his barn, he looked like the criminal he was, flashy, avaricious, sly. She had thought to pull a bag of Brach's buttermints out of her purse, nudge them onto the table, but immediately realized how childish a notion that had been. It was as if some part of her were still Marylou's age, still acting out.

Throughout dinner, Eleanor confabulated. Proved mendacious, chock a block with fibbery. Lying through her teeth made her delirious. And Mr. Bailey was clearly flirting with her. Eleanor excused herself to go to the ladies' room. She swayed past other couples, huddled intimately in wooden booths. Perhaps this was a den of thieves and murderers, no--souls, a Dantean lower rung. Who knew? In the bathroom, she zeroed her face close to the spotty mirror. Oopsie. Some of her navy eyeliner had smeared under one eye. Her wig needed readjusting, a lick of her own red hair was poking through. On the way back, she determined to ask Mr. Bailey—Richard--all about himself. Draw him out. So far she had talked on and on, answering all his questions about her made-up self. What would spring his lock? Should she ask about his father? His childhood? What would Drew have done? For one, she would never have downed three martinis.

But he was gone. Nope, she found him up front, paying the bill and sucking, detestably, on a toothpick.

"I’d like to show you the horses I have for sale. You should ride, you know, not just your daughter."

" don’t know how."

"I could teach you. Private lessons, Eleanor. You have excellent posture."

She followed his shiny black Mercedes in Neil's white, ailing one, careful to keep the spiked tip of her high heel from catching in the floorboard, praying the car would chug stolidly along. He walked her through a series of barns; it grew noticeably darker, more isolated, more stalls were empty. For a moment, Eleanor entertained the scenario that this man was going to topple her into a bed of straw, demand she write him a fat check, slay then bury her in the horse-smelling dirt, smack beside Mrs. Brach. Eleanor lagged, observed how bandy-legged he was, how he walked with an unpleasant, cocky swagger. It had not escaped her detective's attention that his employees treated him with a mix of servility, fear and something slightly mutinous, ripe for betrayal. He had no friends among his help, she had seen that. Probably no friends at all. Now, in what must be the darkest, farthest barn of all, he waited for her, then very lightly, began to steer her this way and that as they moved. When she stumbled, he caught her at the waist, and she thought she smelled -aftershave coming from underneath his maroon turtleneck. Turtle neck? She had an insane impulse to giggle. Hardy-har. Instead, she hiccuped.

"Here he is. Thoroughbred. Four years old."

"An ex-racehorse?" Hiccuped again.

"Very good. How did you know? I've got this other one for sale as well. Over here."

He did not love these horses; she could see that. They were investments, horseflesh. Such a contrast to Marylou. He was hypnotizing her. She felt drugged. Had Mrs. Brach stood here like this? Were these the same horses he had tried to sell her? She felt Mrs. Brach hovering nearby. Her corpse might be lodged somewhere under Eleanor's unsteady feet, but her busybody ghost was darting about.

"Horses are among the most sensual creatures on earth. I have learned a great deal just being near them." Saying this, he tightened his arm around Eleanor's waist, drew her close, an odd sensation as he was a good two feet shorter, a pipsqueak really, but what a tribute to his criminal seductiveness that she allowed him, that she could imagine him leading her into an empty stall, nudging her dress up over her hips, over her head (after which he would be confronted with the bustier, with having to wrestle it off her). But then Eleanor's purse slipped off her shoulder, hitting the dirt with a soft ploffing sound. The bag of Brach’s buttermints tumbled out.

He was smooth as silk, pushing the pink-and-purple striped bag back into her purse, slipping its strap back up her arm. One of the horses stretched out its long neck, to stare at her.

"I have to go."

"Oh no. It's much too early. Let's just go for a little drive. I want to show you something."

So Eleanor sat hiccuping in Mr. Bailey's car, which smelled of tobacco and something else (fee fi fo fum...blood? bone?), sailing right past Mrs. Brach's mansion (which Eleanor had seen before), a bloated old colonial, with an ostentatious, brass-tipped iron fence in front of its circular drive, like an embassy gate, and fat lot of good it had done in saving the poor woman. Was Eleanor imagining that Richard Bailey took his foot off the gas, the car slowing to a snail's pace, as they passed the house? He was drinking from a flask now, offering her a swig, but she had to keep her wits about her, so Eleanor refused. Just past the Brach mansion, he swung the car down a steep narrow road that led to a small parking lot hemmed in by large, dark trees. The parking lot was empty, and beyond it, she knew, for she had taken Marylou to this beach several times last summer, was the lake. When he came around to her side, opened the door and held out his hand, Eleanor took note of his black leather gloves. Where had those come from? Gripping her hand with alarming strength, he walked Eleanor down a small set of tiered wooden steps. There was the playground, the curly slide, merry-go-round, bucket swings, unmoving and ghostly, ominous without children or the sounds of children. They scuffed through the sand to the edge of the lake, where a silvery jumble of alewives, lake fish small as clothespins, had washed up dead. Eleanor felt gloomy. Philosophical. He still had not spoken and now stood, gloved hands clasped behind his back, facing a lake vast and treacherous enough to suggest the sea. People lost their lives to its waters every year. She was convinced he was not thinking of the lake, but of what was directly above him, on the land above him, the silent, unlit a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...