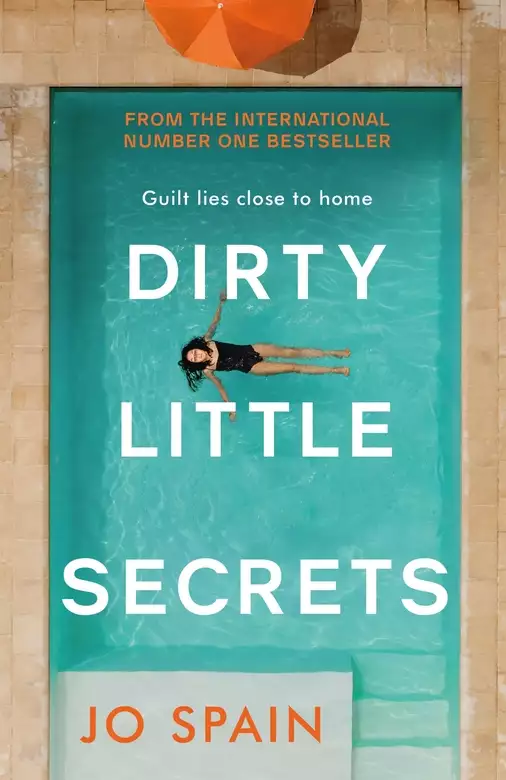

Dirty Little Secrets

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

FROM THE NUMBER ONE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE CONFESSION AND THE PERFECT LIE

Six neighbours, six secrets, six reasons to want Olive Collins dead.

In the exclusive gated community of Withered Vale, people's lives appear as perfect as their beautifully manicured lawns. Money, success, privilege - the residents have it all. Life is good.

There's just one problem.

Olive Collins' dead body has been rotting inside number four for the last three months. Her neighbours say they're shocked at the discovery but nobody thought to check on her when she vanished from sight.

The police start to ask questions and the seemingly flawless facade begins to crack. Because, when it comes to Olive's neighbours, it seems each of them has something to hide, something to lose and everything to gain from her death.

The thrilling psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The Perfect Lie, perfect for fans of Liane Moriarty, C. L. Taylor and Sarah Pearse.

PRAISE FOR JO SPAIN, THE HOTTEST NEW TALENT IN PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLERS

'Enthralling'

JP Delaney

'Chilling'

Sunday Times

'Arresting'

Sunday Express

'Brilliant'

BA Paris

'Gripping'

Best

'Compulsive'

Sunday Mirror

'Addictive'

Michelle Frances

'Refreshing'

Express

Release date: February 7, 2019

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dirty Little Secrets

Jo Spain

In every corner, every whisper.

They just didn’t know it yet.

The bluebottle had no idea it was about to die.

It zipped upwards in the blue sky, warm sun shimmering on its wings, bright metallic stomach bloated with human skin cells and blood.

The bluebottle didn’t see the blackbird swoop, beak open in anticipation. It didn’t hear the satisfying crunch that brought an untimely end to its short, blissful life.

The blackbird continued its descent. There, just beyond the sycamore, streaming from the chimney of the cottage, were more mid-flight snacks. Hundreds of them – fat, juicy, winged insects.

The bird didn’t see the boy, with his Extreme Blastzooka Nerf gun and the bullets he’d modified to cause maximum damage from what was supposed to be a minimum-impact toy.

When the missile hit, slate-coloured feathers exploded in all directions. Death and gravity cast the bird onto the top branches of the tree, from where it thump, thump, thumped the whole thirty metres down to a soft patch of grass below.

The boy, breathlessly running towards his felled prey, didn’t see his mother throw open the kitchen door and bear down on him – the bird’s squawk and the boy’s squeak had jolted her from all thoughts of her absent lover.

Instantly, she saw what her son had done.

But before she could grab him, the boy pointed up and said, with more awe than even the dead bird had incited: ‘Fuuuuck!’ And despite the itch to now punish him twice as hard, the mother’s eyes were drawn to the cloud on the periphery of her vision, a black, menacing, humming mass of bluebottles rising out of next door’s chimney.

The mother clamped her hand over her mouth. That swarm could only mean one thing, and it wasn’t anything good.

Whatever had happened next door, the mother certainly hadn’t seen that coming.

*

Once upon a time, they’d all tried to be more neighbourly. As recently as a couple of years ago, that effort had taken the form of a street party.

Nobody could remember who had suggested it. Alison, a newbie at the time, reckoned the street party was Olive’s doing. Chrissy thought it was Ron’s. Ed presumed it was David’s. Nobody supposed George had come up with it. Not because he wasn’t a nice guy, but he was painfully shy and you just couldn’t imagine him saying, Hey, let’s have a bit of a party, mark the start of the summer hols!

George, though, had put in the most effort. His house, number one, was the largest on the Vale and, therefore, he clearly had the most money (well, his family did – they all knew his father owned the property). That day, George, very generously, brought out four bottles of champagne, a crate of real ale and giant-sized tubs of American toffee candy and wine gums. They were added to the haphazard mix of sweets and savouries already laid out on the trestle table. The sugary wine gums sat between the large bowls of Jollof rice and fried plantains that David had provided.

The adults had floated around each other nervously, despite the fact that most of them were professionals, used to networking and performing. Matt was an accountant. Lily a school teacher. David worked in investments. George was a layout graphic designer. Alison owned a boutique. Ed was a retired something or other – whatever he’d done, it had left him very wealthy. They all had money, in fact. Or at least appeared to. They were social equals and the majority of them had lived in proximity for years.

And yet there was a shyness amongst the grown-ups of Withered Vale. In a domestic setting, out of the suits and offices, metres from their own private abodes, each of them felt an odd sense of discomfort, like they should be more relaxed than they were. Like they should know each other more than they did.

The children, forced into being the centre of attention and with far too much responsibility on their tiny number, had awkwardly played football in an attempt to entertain. The twins were useless. Wolf kicked the ball with such intensity it was like it was diseased and he needed to clear it as quickly as possible. Lily May, his sister, defended herself, not the goal, twisting her body in knots any time the ball was aimed in her direction, at all times nervously sucking the ends of her braids. Cam, a couple of years older and many degrees rougher, was brutally violent, with John McEnroe’s indignant temper whenever he was called to order. And Holly – well, she stood slightly aside, old enough to babysit, too young to be in the adults’ company, painfully self-conscious and bored and mortified.

Somehow, despite the alcohol, the generous food portions, the sun’s gentle warmth and Ron’s best attempts to get an adult football game going, the party just didn’t come off.

If you’d asked any of them why, they’d have all shrugged, unable to put a finger on it.

But if you’d made them think hard . . .

Olive Collins had moved from group to group, chatting to the women, harmlessly flirting with the men, trying to amuse the children, generally being a pleasant, sociable host.

Of all the seven homes in the privileged gated estate of Withered Vale, Olive’s was the smallest and the one that stood out as the most different. Of all the residents, she was the one who probably belonged the least. Not that anybody would think that. Or say it, when they did.

The horseshoe-shaped street was a common area. And with the exception of Alison, nobody believed the party had been suggested by Olive.

Olive preferred one-to-ones.

But she’d taken over. Olive, Withered Vale’s longest resident, had an awful tendency to act like she owned the place.

Slowly, they peeled off. Chrissy, a reluctant attendee in the first place, steered Cam firmly by the shoulder towards home; Matt sloping loyally behind his wife and son. Alison linked arms with her daughter, Holly, smiling and thanking everybody as they left. Ron, the singleton, made away with two bottles of ale and a cheeky wink. Ed half-offered to keep the party going in his house until his wife, Amelia, reminded him loudly that they’d an early flight the next day. David, eager to return to his own kingdom, brought the twins Wolf and Lily May home, all walking in a row like ducks.

Lily told David she’d follow on shortly and offered to help George carry the remains of the crate back to his house. Of all the residents, these two had managed to strike up an unlikely but genuine friendship – just chit-chat on the footpath, little more, but some neighbourly engagement in an otherwise very private estate.

Only Olive was left, folding up the chequered tablecloths she’d supplied.

‘Olive looks a bit sad,’ George remarked, when they were out of earshot.

‘Does she?’ Lily said, casting a discreet backwards glance at their neighbour, the ponytail of dreads she was wearing in her hair that day swinging on her bare shoulders as she turned.

Olive was pulling together the corners of the cloth, mouth turned down, fringe falling into her eyes, her cardigan buttoned up to the neck. A lonely figure.

‘Well, you’re an eligible bachelor, George,’ Lily said.

‘And you’re the neighbourhood saint,’ George retorted.

‘I have to put the twins to bed.’

‘I have to put myself to bed. Alone.’

They both smiled tightly. Neither could bring themselves to invite Olive over for a nightcap.

Their neighbour was always perfectly amiable but both Lily and George knew the wisdom of the saying ‘if somebody is gossiping to you, they’re gossiping about you’.

‘Maybe Alison . . .’ Lily said, catching sight of Holly’s mother making her way back down her drive towards Olive. Alison hadn’t yet got the measure of everybody but everybody reckoned they had the measure of her. She was a soft soul. Kind.

‘Ah,’ George said. They were off the hook. Alison chatted away to Olive and the other woman nodded happily. Then the two women made their way into Olive’s cottage.

Thank goodness for lovely Alison.

Poor Olive. She was so very hard to relax around. Even then.

Even before she properly began to wreak havoc on the lives of her neighbours.

No. 4

At first, there was just me. Before my house had a number. Before the others arrived.

I hadn’t intended to live on the outskirts of the village on my own. I’d ended up there by chance. I couldn’t afford any of the houses on sale on the main street. Or the side streets. Or the streets off the side streets. My income from the health board, where I worked as a language therapist for children, was good. Just not good enough.

Priced out of buying a house where I’d grown up, one day in 1988 I drove over the bridge and out past the pretty woods that dotted most of my home county.

Just beside the woods and before the fields that made up John Berry’s land, I saw the cottage. Its owner had died months earlier and we all knew his son, by then an illegal immigrant in the States, had no plans to return. A home wasn’t much use when you couldn’t get a job for love nor money and anyway, nobody left America once they’d got in.

It was just a matter of the estate agent phoning and telling him somebody was willing to take it off his hands. I got it for a song and a promise to ship some personal belongings over.

‘Withered Vale?’ my mother said, eyes wide and appalled. ‘Why would you pick there, are you mad?’

‘It’s picked me,’ I laughed. ‘It’s the only place I can afford.’

My parents only knew the Vale because of its history. At the start of the twentieth century, an over-enthusiastic and most certainly drunk farmer had decided to tackle pests on his land by going hell for leather with arsenic spray. He poisoned all his crops in the process – they withered and died in the fields.

‘But it’s miles away,’ my mother protested. ‘How will I get by without you?’

‘The cottage is minutes away in the car,’ I said. ‘I’m twenty-six. I can’t stay living at home forever!’

In truth, it wouldn’t have mattered if I’d gone to live on the moon. I still had to call around to my parents’ every evening on the way home from work, at least until they both died, a year apart, a decade later.

After the initial period of grieving, I realised I was glad to be able to go directly home each night. The remoteness and the single life didn’t bother me at first. I was exhausted from all the running about, before and during my parents’ illnesses. I could imagine nothing nicer than arriving home from work to a lovely, clean house, with a takeaway, a video, a bottle of wine; nowhere to go, no duties to fulfil. I happily went on like that for, oh, I don’t know, at least a year.

It’s true what they say. What’s seldom is wonderful and my routine soon became, well, routine.

And as time wore on, I became lonely.

I’d no siblings and no close friends and I hadn’t planned on being a spinster. There was no revelatory moment, no decision, when I thought, I’m so thrilled with this life, I think I’ll just stay on my own.

If anything, I’d been convinced I’d follow the traditional route.

I wasn’t a dainty and pretty woman exactly, but I certainly wasn’t ugly and boyfriends were never a problem. For whatever reason, though, I never met anybody I was willing to settle with, or for. I was destined to be just the one.

But I did enjoy company.

So, in 2001, when John Berry sprang it on me that the land under my cottage actually belonged to him and he’d sold it to a property developer to build on, the only concern I had was whether my home would remain standing.

‘Of course!’ he assured me. ‘You don’t have the freehold, but you’ve bought the place and it’s yours. This fellow would have to buy you out but he has no plans to. He’s going to build around you. He’s not going mad, either. Just a few houses to see how it goes. It’s going to be an exclusive development – large, fancy homes for rich, important types. The ones who like their privacy. Withered Vale, right next door to Marwood, a whole village on your doorstep. Everybody will want to buy a place.’

‘Is he really keeping the name?’ I asked, amazed. Pockets of these developments had begun to spring up all over the country at the turn of the century, copycat American-style estates for the privileged few. But they all had names straight from the LA handbook: The Hills; The Heights; Lakeside.

‘Oh, he’s keeping it,’ Berry said. ‘He loves it. Thinks it will make the place unique. He reckons he’s going to blow the property values around here out of the water.’

One by one, I watched the houses go up around me in a semi-circle. While they were big, each one was different, and all had a quality of design. And the fact each house was unique meant my cottage, despite its far smaller size, didn’t stand out quite as much. In fact, when he brought the landscapers in, the developer added the same hedge border as mine around all the properties. It gave the Vale a feeling of continuity, he said.

Sadly, it was just a tad too tasteful for him. He lost the run of himself and turned us into a ‘gated’ community. He hung a big wrought-iron sign over the railings in case anybody struggled to find Withered Vale, the only outpost for miles between Marwood and the next village on the other side of the woods.

I’d gone from being a one-off cottage on the edge of civilisation to part of an elite club.

As the families moved in, one by one, I greeted them generously and genuinely. The homes were numbered one to seven and my cottage, after some initial wrangling with the developer about where I would sit on his patch, was number four.

Right in the middle of everything.

Some of them came and stayed, some of them moved in and moved out and we got new neighbours. They were all blow-ins to me.

I tried to be friendly with everybody. I hope people remember that. That I tried very hard.

The police men and women beavering around my body right now don’t know anything of my story yet. They don’t know anything at all, really. They’ve spent the last twenty-four hours trying to rid the house of flies and maggots and the pests they know are here but can’t see – the mice and rats. The gnawing at my fingers and toes speak to their existence. It’s amazing there’s anything left of me.

It’s the heat, you see. After an unusually cold spring and early summer, I was doing okay, sitting there on the chair, silently decomposing. The same chair Ron from number seven bent me over for three and a half minutes of mind-blowing passion the night before I died, leaving with my knickers scrunched up in his pocket.

I hope, for his sake, he’s got rid of them.

Then late May came and the weather turned on its head, sending temperatures soaring and bringing all sorts of nastiness into my living room.

It’s amazing how long they left me, my neighbours. Not one, not a single one, came to check on me. Not even Ron. And Chrissy only rang the police when my cottage looked like a public health hazard.

Was I really that hated?

Those poor detectives. I almost feel sorry for them. It’s going to take them forever trying to figure out who killed me.

Frank Brazil had never claimed to have a strong stomach. And he wasn’t going to start pretending now, in the presence of this body – this carcass. Every time his eyes happened on the blackened, liquefied lumpen form, bile threatened to explode from his oesophagus.

Even his partner Emma looked slightly less orange than normal, her naturally fair skin a few notches paler under the caked foundation cream.

‘It’s utterly disgusting,’ she said, decisively. She hadn’t stopped talking since they’d arrived. Frank prided himself on being a modern man – he held to the philosophy that there was no difference between men and women, that the fairer sex were equal – in fact, superior – to men in almost every way. First his mother, then his lovely Mona, had kept him right in that regard.

But, Christ . . . Emma. He could not get his head around the girl. So young, with so many opinions and all of them so fixed!

‘The poor woman. What has happened to community? How could her neighbours not notice she wasn’t around? You’d think one of them would have knocked and raised the alarm. You should see what they’re saying on social media about the people who live here. And where are her family?’

Frank shrugged. It wasn’t that he didn’t agree. Frank’s home was in an old council housing estate that had been gentrified and while many of his neighbours these days were students or young professionals, there was still a community feel to the place. Only last week they’d had a football tournament of sorts on the green that the houses surrounded. Dads, city-boys, students and children alike all joined in.

If one of his neighbours died, he’d notice they’d gone missing in action and there were far more than seven houses in his estate.

‘It’s just plain wrong, elderly people being left alone like this,’ Emma continued. ‘I hope the government runs those ads again, the ones about checking on vulnerable pensioners. They’ll have to, in the wake of this.’

‘Elderly? Emma, she was fifty-five! That’s two years older than me.’

‘Well, I’m not being funny, Frank, but you are retiring in three months,’ Emma said, and Frank clamped his hand to his forehead. How could you ever explain to a twenty-eight-year-old that fifty-three was not old? That he was retiring because he was tired and sad and no longer cared? He’d been working in this job longer than she’d been alive and he’d seen too much. He’d lost empathy. When that went, you had to go too. Every sensible copper knew that.

He turned away from Emma and peered through the window. Somebody had raised the blinds to let light into the room. The entrance gates had made it easy to isolate the crime scene – there was no press throng, it was just the police and emergency vehicles inside the perimeter. And the neighbours, who were still holed up in their houses, having woken up to a shitstorm of epic proportions.

Forensics had taken initial DNA from the scene. There was plenty. Too much, in fact. If it wasn’t accidental death or suicide, if it turned out Olive Collins had been murdered, they had tonnes to work through. They’d even, according to the speculation of the forensics team, potentially picked up traces of semen from the floor beside the body.

‘She must have had a chap,’ he said aloud, to himself and to nobody.

‘Do you think so?’ Emma said. She pulled on her gloves and picked up a framed photograph from the dresser. Crime Scene was finished in the sitting room – every surface dusted and swabbed, every inch photographed – but the detectives still wore baggies over their shoes and blue rubber gloves on their hands. The picture showed a younger Olive in a large-collared blouse with a striped jumper last seen circa 1985, sporting a bowl haircut. ‘She wasn’t particularly attractive. And she was . . .’ Emma trailed off like she’d thought better of her next sentence.

He shrugged.

‘If she was willing . . . That’s usually enough for most men. Anyway, I wouldn’t go judging her looks on a thirty-year-old photograph; the entire population looked ridiculous in the eighties. Or on what’s in the chair, there. Let’s find a more recent picture of her.’

The deputy state pathologist appeared in the doorway.

‘I’m ready to move the body.’

Hovering behind him was the head of forensics, the likeable, down-to-earth Amira Lund. Frank had a lot of time for Amira, and he liked to tell himself it wasn’t just because she was a very attractive woman – big almond eyes, dark skin, long luscious black hair (that he rarely saw, to be fair, given all their interactions took place with her ensconced in a white suit).

‘Frank, got a minute?’ she asked.

‘They’re about to move the body,’ Emma said.

‘Abso-fucking-lutely I have a minute,’ Frank said. There wasn’t a chance he was hanging around to see Olive Collins’ corpse being shifted from the chair into a body bag. Christ knew what was under that saggy mess. His skin crawled just thinking about it.

‘You’re in charge,’ he told Emma, who struggled to hide her delight before she realised what she was about to witness. The smile died on her face.

Frank followed Amira out, ducking his head under the door frame and emerging into the small hallway that ran between the sitting room and the kitchen. He knew already that it led off towards the two bedrooms and bathroom. The cottage didn’t have an upstairs but it had a large enough ground-floor footprint.

‘Through here,’ she said, bringing him into the kitchen. Frank stood aside to let one of her team come out first, his large hands filled with evidence bags.

‘Has God said anything yet?’ Amira nodded back in the direction of the sitting room.

‘He deigned to tell me when I arrived that it’s difficult to pick up anything from a body in that state – truly, a revelation of biblical proportions – but there are no bullet or knife wounds, no old blood stains. Nothing you don’t know yourself. However she died, it was gentle enough. Maybe she’d a heart attack. Or she took a bottle of pills and just sat down to watch telly, drifted off. The lads who found her said the television was on stand-by, like it had switched itself off after a time but was ready to go with a flick of the remote.’

Amira shook her head.

‘I don’t think that’s what happened.’

Frank sighed. Sudden death was always treated as suspicious. They had to examine all the angles, tick all the boxes. But in the end, all it really created for the police was paperwork. Lots and lots of it.

He’d been happy to come out here this morning because admin was all he was good for. Emma wanted complex, high-profile cases. Day-long interrogations. Sensational trials. She was young, she had the energy for it. Anybody who looked like they got up at the crack of dawn every day just to apply make-up had the energy for anything.

All Frank wanted was an eight-hour shift where nothing of note happened, after which he’d head home to a frozen pizza, David Attenborough on the TV and a good night’s sleep free from nightmares.

‘What is it?’ he asked, tentatively.

‘The boiler was pumping carbon monoxide into the house.’

Frank cocked his head, raised a hand, pulled at the tuft of reddish-brown hairs over his upper lip.

‘Accidental death from ingestion of poisonous gas. Very sad. They should make those CM alarms obligatory.’

Amira shook her head again.

‘Nope. Not accidental. Come over here.’

Frank followed her to the kitchen door, every step heavy and resigned. He watched as Amira stood on a chair and traced blue-gloved fingers around the vent over the door.

‘What’s that?’ she said.

He took his place on the chair.

‘Tape,’ he answered, and his stomach felt funny.

‘Tape,’ she repeated. ‘Every vent. The doors and windows are well insulated, nothing needed there.’

‘What about the front door? Didn’t the neighbour say something about the letter box being taped off?’

‘It was just the letter box and it was masking tape, not clear tape. And there are fingerprints on it. A couple of sets. One is probably the neighbour who found her. The other, if I were to hazard a guess, is probably the victim’s. She had a postbox attached to the front wall, maybe she didn’t need or want people sticking post in the door.’

Frank, drowning, clutched for the lifebuoy.

‘So, either Olive Collins had an aversion to fresh air or her death was planned. She wanted the method she chose to be effective. She knew the boiler was leaking or she blocked the pipe. Is it an old one?’

‘No. It’s fairly new. It’s in that cupboard on the wall behind you. It’s not long since it was serviced, according to the sticker on its front. But the caps were unscrewed and the flue stuffed with cardboard. Manually.’

‘Well. Suicide it is, so. She taped up all the air vents. I’m surprised she didn’t block the chimney. That’s what drew the neighbour’s attention – the bluebottles.’

‘There was nothing in the chimney,’ Amira clarified. ‘But that wouldn’t have mattered. The chimney flue is narrow and not sufficient to empty a home of carbon monoxide. She had a painting propped in front of it as well. There was some ash in the fireplace from paper she must have burned, but no open fires for her.’

‘Sorry, Amira, what’s the point? Something is giving you itchy knickers.’

‘I’ll tell you what’s upsetting me, Frank. This house is crawling with DNA. For a woman who was left dead in her sitting room for nigh on three months, it looks like she had an awful lot of visitors in the run-up. The only place we haven’t picked up fingerprints is on the tape over those vents. Nor from the pipes attached to the boiler. They were cleaned.’

‘Shit.’

‘Yeah.’

‘But – come on, it’s still more likely she’d have done it herself. How could somebody have taped up all the vents without her noticing?’

‘It’s not like it would take that long, Frank. And, as you can see, it’s clear tape. I didn’t notice it until we checked the boiler and I started to look closely.’

‘I don’t know, Amira. As a manner in which to murder somebody, it’s fairly diabolical. I’d go so far as to say it’s a little over-imaginative for this day and age.’

Amira shrug. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...