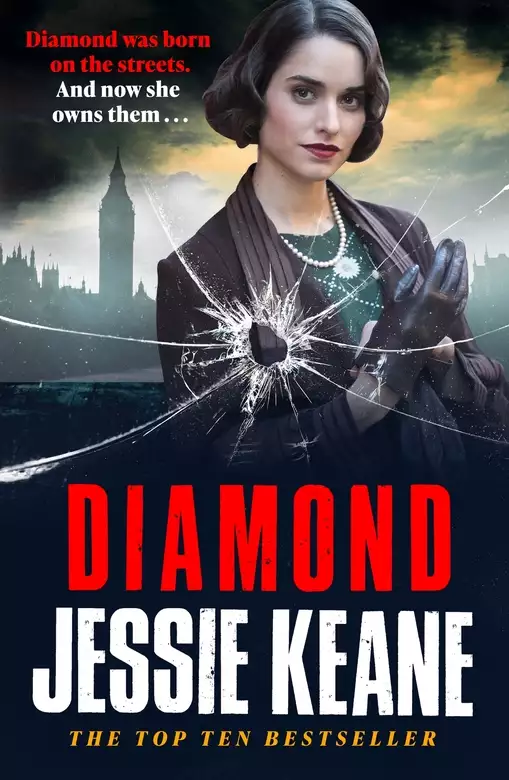

Diamond

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The thrilling new crime novel by top ten bestselling author Jessie Keane . . .

BEHIND EVERY STRONG WOMAN IS AN EPIC STORY...

In the early years of the last century, a desperate young girl changes her name and flees the confines of her brutal, dominating gangland family in London. Now calling herself 'Diamond Dupree', she goes to Paris to become an artist's model but the world there is different to what she had supposed it would be and she soon falls on hard times. When she manages to escape at the end of the First World War, she leaves behind her a mystery - and a dead man.

Back home in London, she reluctantly re-joins the Soho family 'firm' she'd once been glad to leave behind. Having grown tougher during her time in Paris, she soon becomes a force to be reckoned with, a feared and respected gangland queen. But then she meets Jacob Dunne, the youngest son of a wealthy aristocratic family, and sparks fly.

But can she escape the long arm of the law and the hangman's noose, when the crimes of her past finally catch up with her?

For fans of Martina Cole and Kimberley Chambers, as well as viewers of Peaky Blinders, this is historical crime fiction at its most compelling.

(P) 2022 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Release date: February 3, 2022

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Diamond

Jessie Keane

1909

When the Boer War was going on over in Africa, Warren Butcher and his Butcher Boys ruled the streets around Soho. Everything was fine. Then the Austrian Wolfe crew under Gustav Wolfe came to London and snatched the business out from underneath the Butchers.

It was bad in one way – very bad – but good in another, because Warren was forced to hastily decamp to Paris and there he met Frenchie, an artist’s model, who would become his exotic-looking wife and Diamond Butcher’s mother. Warren didn’t speak French, and Frenchie had only a little English, but they learned from each other, and the language of love soon overcame their differences. Warren fell head over heels for Frenchie and together they settled down to married life.

Prosperity followed. Paris was good to the Butcher family. They started with one nightclub, then expanded. One more. Then another. And so on. Buying, decorating, dreaming, creating their dream. They were happy in Frenchie’s golden city. Deliriously happy. And getting rich.

Then came the three children, in quick succession. Frenchie wanted to give her babies French names, but Warren was insistent. He was English, to his bones.

‘Diamond for a girl,’ he said. ‘And she will be a diamond, won’t she? A little jewel. And Aiden, I’ve always dreamed of that name if I had a son.’

‘And if there are two boys? What then?’ Frenchie teased him.

‘Owen,’ said Warren.

So along came Diamond, then Aiden and then finally – a last hurrah for Frenchie, by then a glamorous grande dame in her forties – Owen.

Diamond loved both her younger brothers. Aiden was a nightmare of a kid, lively to the point of mania, stuffing his pockets with all kinds of rubbish, running everywhere full throttle, jumping off shed roofs and forever getting into mischief. He was always dirty, always covered in mud and blood, but he was sweet too, and smiley, and Diamond loved him very much.

She fussed around after Owen too, who sadly was slow-witted because the cord had knotted around his neck during the birth, poor thing. As a consequence of his disability, Owen was Aiden’s opposite: peaceful, almost slothful, happy with his colouring books at the kitchen table, alarmed by loud noises or shouting, needing to be shielded from the world.

‘Red and yellow make orange,’ Diamond told Owen, showing him with the crayons. ‘And look, Owen – red and green make brown. And blue and yellow make green. You see?’

Owen was delighted. He laughed and kissed her cheek and she hugged him, ruffling his dark hair and smiling at his pleasure in such simple things.

Diamond loved Aiden and Owen. She worshipped her dad. And she adored her glamorous mother Frenchie, who had taught her daughter to speak her native tongue so that she was fluent in the language, perfect in her pronunciation.

‘She could pass for a Parisian,’ Frenchie told Warren proudly.

Then disaster struck. Gustav Wolfe – who had previously seized all the Butcher holdings and driven them out of London – expanded across the Channel and into Paris. Sheer force of numbers defeated the Butcher clan. The Wolfe mob descended on them, snatching away their six Parisian nightclubs – the Pompadour, the Miami Beach, the Metropole, Ciro’s, the Lopez and the Cabaret de l’Enfer. Again, Warren Butcher had to run – or die.

‘It’ll be all right,’ Warren told his wife.

But Frenchie didn’t think so. What she thought was this: that the hated Wolfe mob would hound them until their dying day. And Diamond, from an early age, believed her mother to be absolutely right.

2

‘Maybe we’ll try Manchester,’ Warren said to Frenchie. ‘Or Birmingham.’

‘You mean, we will run?’ sniffed Frenchie. ‘Run away from Gustav Wolfe and his mob of thieves and cut-throats?’

They’d returned to Soho, to Warren’s home town of London, with all their belongings – which included a massive full-length portrait of Frenchie in her prime. Warren didn’t want to go anywhere else. But he had a family to think of now. If Wolfe cut up rough, what might become of Frenchie? Of Diamond and Aiden and Owen, his kids who he loved more than life itself? What if something happened to them, and it was his fault, because he hadn’t moved quickly enough to save them, to spare them more conflict?

But then Warren started to hope. Everything was quiet, after all. On the strength of this, ever hopeful, he used the cash he’d saved up in Paris to buy a house, and hung Frenchie’s fabulous portrait at the top of the stairs. With what remained, he bought a club called the Milano over in Wardour Street and the Butcher family called it theirs. Frenchie set to with great gusto, decorating the club interior with vivid reds and luscious golds. She was so proud when the opening night came, and there was dancing to a band, the drink flowed like water, everyone had a fabulous time. Then when all seemed to be going well, one dark rainy night someone put a lit rag through the letterbox of their house.

Warren was a bad sleeper – that was all that saved them. He was coming down the stairs to get his cigarettes and make a brew just before midnight when he saw flames erupting on the doormat. He ran down and stamped it out. Smoke billowed. He opened the front door and stepped out, heart thumping, staring around. The rain fell, hissing hard as a thousand snakes. But there was nobody to be seen. He tossed the destroyed mat out onto the path, still smouldering. The burned rag, too. Frenchie, having heard him opening the front door, was coming down to see that he was all right.

‘Chéri, what . . .?’ she asked anxiously.

Warren stepped back inside. His head was spinning. So here it was, at last. That bastard Wolfe was never going to let this go. The worst of it was, Warren knew that once again he was outgunned. Most of the coppers around the manor were already in the pay of the Wolfe mob. And Warren had lost touch with many of the boys who’d worked for him around the clubs, pubs and snooker halls he’d once run in London – before Gustav Wolfe had snatched it all away from him. The Wolfes had bigger numbers, but Warren had practically no-one to call on. His kin were up north, they hadn’t been in touch for years. He’d never got on with his brother Victor, and his parents hadn’t wanted to know either of them.

Now, this.

If he hadn’t – by sheer chance – come downstairs, they might all have been dead by morning.

Frenchie was staring at him, pale and clutching at her throat in terror. ‘Was it them, you think?’ she said quietly.

Upstairs, their kids were sleeping. It chilled Warren to the bone, the thought of what could have happened.

Maybe Manchester would be good, Warren thought. Or – yes – even Birmingham.

But the Wolfe clan had tried to burn him out. Rage churned in his belly and clutched at his chest. They could have killed his kids. His wife. And now he was thinking of turning tail? Running away?

Just how far could you run before you got sick of it? Before you knew you had to stand your ground at last, and fight?

This far, thought Warren. And no bloody further.

He reached up, furious, and snatched down his coat, pulling it on.

‘Where are you . . .?’ Frenchie demanded, but he was already gone, out the door and away.

3

‘You did what?’ Frenchie said two hours later.

She’d been frantic, pacing the floor since Warren left, wondering what madness he would commit. Warren was hot-tempered at the best of times. Would he go, knock on the Wolfe door and call Gustav out? That would be crazy, but she wouldn’t put it past him.

Now he was back – thank God! But what had he done?

‘I put a lit rag through his letterbox,’ said Warren. ‘See how the fucker likes that.’

Frenchie couldn’t believe it. Stupid, stupid, stupid, she thought. But she said nothing. In her mind, she was already gone. Manchester, yes. They’d try there. Anywhere, where there was no Wolfe mob waiting to snatch their livelihood away from them. But she was broken-hearted. In London, the Wolfes had smashed Warren’s living. In Paris, the Wolfes had smashed them again. Now the Butchers had just one London club, their absolute pride and joy, the Milano, and she knew the Wolfes would take that too. She knew it. There was nothing for the Butchers to do now but flee. Again.

But before they could gather themselves, put the club on the market, a note – not a lit rag – was shoved through the letterbox. Frenchie watched as Warren opened the envelope and spread out the stiff sheet of paper inside. She read it, over his shoulder.

Tonight. Eight o’clock. Outside the Milano.

‘Oh God,’ said Frenchie, frozen with fear.

Warren scrunched the note and envelope up, stuffed them into his pocket.

‘I’ll be there all right. Mob-bloody-handed,’ he said.

***

The Milano didn’t open that night. Out in the street at the front of it, the clock struck eight and Warren and what boys he could muster were there, ready for a ruck. Then one by one, the Wolfe lot started to emerge from the shadows. Warren gulped as he saw them swelling in numbers; there were hundreds of them. The streetlights glittered off cudgels, knives, axes, bike chains. Then Gustav Wolfe stepped through the crowd, big as a barn door, his sandy hair swept straight back, his eyes black pinholes as he stared, half smiling, at Warren Butcher.

‘You want to call this off then?’ asked Gustav into the sudden silence.

‘No,’ said Warren, thinking of that burning rag on the doormat. This cunt thought he was a doormat, fit only to wipe his dirty Austrian feet on. Well, no more. ‘I heard someone tried to set light to your arse,’ said Warren. ‘Shoved a lit rag through your letterbox. Is that right?’

Wolfe’s smile froze on his face. ‘You think you’re funny, uh?’

Warren shrugged. What the fuck. His hand tightened on the axe he held. He’d sharpened it that morning, sitting at the kitchen table with Aiden running rings around him, Owen peacefully colouring with his crayons and his bits of paper, Diamond sitting gravely at the table, watching him.

‘Enough talking,’ said Warren, and let out a bellow, holding the axe high as he charged.

A roar went up from both sides and then Warren was in the thick of it, crashing into the opposition, pummelling his way in with the axe swinging wildly in his right hand, the brass knuckledusters on his left pounding faces, chests, arms. Bodies were falling, hitting the cobbles, and he was wading further into the Wolfes, falling over men groaning, their heads a mess of blood, slipping and sliding as the cobbles got drenched in it, treading on a hand and then realising it was detached from someone, and there was screaming and he was possessed, swinging the axe, wanting to reach Gustav Wolfe but unable to; everyone was clustering around Wolfe like he was their king and had to be kept safe.

Then there was an impact – a stunning, hideous blow that knocked him down, and he was crawling, half blinded, blood in his eyes and humming in his ears. He dragged himself all of three paces, and then was struck again.

This time, he fell and lay still.

4

They brought Warren Butcher home on a stretcher. What few of his supporters remained were blood-stained, battered, stumbling with exhaustion. They carried Warren into the kitchen and laid him out on the floor.

He was dead.

Frenchie saw it, straight away. His head had been caved in on the left side, baring brain and bone and blood. The life force was gone from him; he was nothing but a shell. She flung herself on his neck, crying, screaming with rage and pain and horror. Diamond grabbed Aiden and Owen and hustled them up the stairs, away from this carnage.

She sat upstairs with her brothers for a while, hearing voices down below, shouts, curses. Owen was trembling, leaning in against her and she had her arm around his shoulders and was talking to him in a low voice, soothing him as best she could. Aiden sat on her other side, saying nothing, but pale and taut as a bowstring.

Finally, she could stand it no longer. She had to know what was happening.

Telling her brothers to stay there, she left the bedroom and went down. She didn’t want to go into the kitchen, but her mother was in there and so she knew she had to. She didn’t want to see her dad again, stretched out dead and cold on the floor. She didn’t think she could bear it. But her mother was there, suffering, so she had to suffer too.

Bracing herself, shivering with dread and fighting back tears, Diamond went into the kitchen. But there were no men there. There was no body. There was only Frenchie, sitting in the chair by the fire, hunched over, her hands to her face. She looked up as Diamond came in, her face smeared red where she had been clinging on to Warren. She held out a hand. Diamond rushed forward and took it, hugging her mother hard. She could smell her father’s blood. She could feel Frenchie’s tears, drenching her shoulder as Frenchie clung to her in desperation.

Frenchie sobbed. ‘I knew it would happen. I told him. But he would never listen.’

Diamond didn’t know what to say. There were no words of comfort she could give.

‘I asked them if they saw him fall,’ Frenchie gasped out. ‘They said it was Gustav Wolfe, it was him who delivered the coup de grâce to my poor darling Warren. I hate that cochon so much!’

Diamond could feel the rage and sorrow seeping out of Frenchie and into her. The Wolfe mob. They’d been a torment to her family ever since she could remember. And now – this. Her dad was dead. What was going to become of them all, without his jovial, reckless, larger-than-life presence?

She hugged her mother while Frenchie sobbed again – wrenching, heartbreaking sobs of absolute despair.

‘They have taken him to the morgue,’ said Frenchie brokenly. ‘My love, my beautiful man, they have taken him away from me. It’s more than I can stand.’

Diamond held her mother tight. There was nothing else she could do. She hated the Wolfes. She hated them and she swore to herself that when she was grown she would have her revenge; she would harm them, in any way she could.

5

Diamond Butcher was just eleven years old when she first met her Uncle Victor at her father’s funeral. She was standing, drenched to the skin, beside her mother and her two brothers at Warren Butcher’s graveside. It was pissing down with rain, hammering her, the droplets so hard that she could barely hear what the vicar was saying.

Anyway, it didn’t matter.

A numbness had engulfed her, ever since that awful night when they’d carried her father home. All that mattered was that Dad was gone. Gustav Wolfe had killed him. The Wolfe clan were their dreaded enemies. Thoughts of sweet vengeance haunted Diamond, day and night. There was a dead wife, she knew that, back in Austria. A son, she knew that too. And a daughter. More than that, she didn’t know or even want to. All of them were evil, bad to the bone. She despised them.

‘Ashes to ashes, dust to dust . . .’ droned the vicar, rain dripping in cascades from his surpliced shoulders, sploshing off the end of his beaky nose onto the open bible in his hands.

This last week had been a nightmare. The police – straight ones, or ones in the pay of Gustav Wolfe, who knew? – had come to call. Looking at them all like they were scum. Asking questions and not even caring about the answers.

Diamond clung on to her mother’s hand at the graveside. She could feel Frenchie shuddering with tears, unable to comprehend what had happened. Now she was a widow. Aiden and Owen, on their mother’s other side, were silent. Nine-year-old Aiden was holding back the tears, determined to be brave now he was the man of the family. Owen, who was just six, wore his usual expression of sweet bewilderment. How could they explain life, death, to him? He knew his colouring books and the kitchen table; that was all. Death and disaster, the horrors of the Wolfe clan, Warren Butcher’s proud, brave and foolhardy fight for survival against insurmountable odds – all of that was beyond Owen.

Now the vicar had stopped speaking and was holding out a small rectangular wooden box to Frenchie. Diamond watched as her mother dipped her fingers into the muddy dirt it contained. She threw a handful of it down, onto the coffin. It landed with a thump that made Diamond’s nerves jitter.

Dad’s in that box.

Hatred and despair roiled in her stomach and she thought she would be sick. She’d been having terrible nightmares ever since the night of the gang fight; she’d been plagued by images of monstrous Gustav Wolfe, hammer in hand, charging at her dad, striking him to the ground. And now, without Dad, they were alone – unprotected.

What’s going to become of us?

At last the ordeal was over. Frenchie was tugging her daughter and sons away from the grave. They would go back to the house – that at least was still theirs, for now – eat sandwiches, drink tea, and stare into a barren future.

‘Come on. Let’s go home,’ said Frenchie, her voice hoarse with tears.

Then a man stepped up through the bucketing rainstorm, blocking their way. He was big – tall, broad, bull-necked, black-haired and – this was strange – he had a look of Dad about him.

‘Frenchie?’ he said as the crowds dispersed.

‘Oh, it’s . . .’ Frenchie gulped, blinking. ‘Victor? Isn’t it?’

The man nodded. ‘Sad day,’ he said.

‘We haven’t seen you in a lot of years,’ said Frenchie. Her voice was flat, Diamond noticed. Not welcoming. Not even warm. ‘Children? This is your Uncle Victor. Your father’s brother.’

‘Let’s get out of this fucking rain,’ said Victor, taking Frenchie’s arm. ‘We got things to discuss, am I right?’

‘I don’t think so.’

She doesn’t like him, thought Diamond.

‘I do,’ said Victor. ‘Come on.’

6

‘Fact is,’ said Victor, who not three hours later was standing in front of the fire in the parlour, his hand on the mantel like he owned the place, ‘you’re in a bind, ain’t that right?’

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ said Frenchie.

‘Yeah you do. Man of the house gone. Wolfe lot breathing down your necks. You’re in trouble.’

All the mourners had departed after the wake and now an uneasy peace had descended on the house. The kids were grouped around the kitchen table. Owen was busy with his colouring-in; he was working on a picture of Mary Pickford, the ‘world’s sweetheart’. Aiden was watching Uncle Victor with wary eyes, Diamond was wondering what fresh hell this day could bring.

Diamond didn’t like the look of Uncle Victor and she could see her mother didn’t, either. Dad had been a big bruiser of a man but he had been humorous, jokey, warm and loving. People had looked up to him, turned to him for advice and direction. Victor was different. There was something cold and smug about him, like his own brother getting himself murdered was a good result, an opportunity, not a thing to be mourned over.

‘Lucky for you I’m here,’ said Victor.

Frenchie was staring at him like he’d just crawled out from under a stone.

‘What does that mean?’ she asked.

Diamond’s eyes moved between the pair of them, her mother and her uncle.

‘That accent. Always did like it,’ he said. He was half smiling.

Frenchie’s stare grew colder. ‘Victor,’ she said tiredly, ‘it’s been a long day.’

‘Then I’ll be brief. It’s obvious, innit? I’ll take over. Handle things. Christ knows, you can’t.’

‘I’d rather . . .’ started Frenchie.

But Victor wasn’t paying heed. He was looking at the kids, his niece and nephews, and his eyes were narrowed with irritation.

‘Better get this lot off to bed, yeah?’ he snapped.

Frenchie rose from her chair, holding out her hands to them. ‘Yes. I had better do that,’ she said stonily. ‘Come along, children.’

***

From that day on, their lives changed forever. Hours later, the two boys were in their room, asleep, and Diamond was in hers, a tiny boxroom tucked up under the eaves. It was luxury, having her own room, when she could remember once having to share, top-and-tailing, with the boys when they’d been little, in France. But she was still awake, unable to close her eyes, unable to rest, when she heard Mum coming up the stairs. And there was another tread right behind hers, heavier, more deliberate.

Quietly Diamond slipped out of bed in the dark and went over to the door. She opened it, just a tiny crack, and peered out. Uncle Victor was there on the landing, with her mother. And her mother was crying.

‘Enough of that,’ she heard him say, and to her shock he pulled Mum toward him and kissed her, long and hard enough to bruise her. Frenchie was struggling to get free. Diamond could hear her own heart, beating hard. She was biting her lip in horror and confusion. She tasted blood.

‘Now,’ Victor said at last. ‘Let’s get on, yeah?’

He shoved Frenchie into the bedroom she had just a few nights ago shared with her husband. Then he paused on the threshold of the room, and looked back, along the landing. Diamond froze, sure that he could see her there. But then he walked on, into the bedroom – and closed the door behind him and his brother’s widow.

7

1912

Now Uncle Victor ruled the roost. He’d taken control of everything after Warren’s funeral and woe betide anyone who didn’t fall into line when he said so. Straight away he’d assembled all the remaining Butcher Boys out in the yard and announced that he was in charge now, and if anyone had anything to say about that, they should speak up.

No-one spoke up.

‘We’re not the Butcher Boys any more,’ he roared at them. ‘I’m Victor Butcher and now we’re the Victory Boys. All right?’

Then it was the turn of the hoisters – the shoplifters – to get their pep talk from the new boss. Mostly female, under Warren’s rule they had been a small and amateurish force. Now, under Victor’s direction they grew in numbers and began to terrorise the high-class shops around the West End. Day after day they set out in tightly organised groups, wearing specially made garments with concealed deep pockets sewn into every layer. Frenchie protested at her daughter’s involvement, which Victor insisted upon.

‘I don’t want my girl ending up in jail,’ she said.

But protesting against Victor’s decisions was like spitting into the wind.

The girls would go into high-end stores and emerge onto the streets wearing five dresses beneath their coats, jewellery slung around their necks, every pocket stuffed full with goods – hosiery, leather purses, whatever expensive item they could lay their hands on.

Several times Diamond was caught inside a store and had to say that she was just taking an item to the light of the door so that she could see the colour better. Once she was chased down the street before she could catch up with her ‘boosters’, two heavy Victory Boys in a car, who took the goods off her and raced away with them. When stopped by the pursuing store detective and searched, there was not a thing on her to be found.

She hated it, but she had to do it. Victor said so. She got good at it, too.

There was something deeply intimidating about Victor, something quick-moving and frightening. One moment he’d seem calm, the next he could erupt into a terrifying rage. Diamond hated him. They all did. He seemed to delight in being cruel. He came into the kitchen, where Owen sat colouring in a newspaper drawing of the doomed Titanic. Frenchie, Diamond and Aiden had shivered when they’d seen the picture, but it meant nothing to Owen. It had been all over the papers that fifteen hundred souls had been lost when the massive and seemingly indestructible ship had struck an iceberg in the north Atlantic. Victor swiped the boy roughly around the head, seemingly playful but intending to hurt.

Whop!

‘Trust a bruv of mine to have a fuckin’ moron for a kid,’ he said, laughing.

Time and again Diamond saw Frenchie bite her lip, swallow the anger she felt at him mocking her dead husband and being so cruel to her son.

‘Victor’s a bastard,’ Aiden would whisper to Diamond. ‘A fuckin’ bastard.’

But Aiden was just a boy, young and weak, no match for a man like Victor. He took over, the dominant male, raking in all the monies from the hoisters, the snooker halls and the club, scaring the shit out of everyone around him. He had even fended off Gustav Wolfe, and that was no mean feat. By some miracle, when Victor arrived on the scene, the Wolfe nightmare receded. He didn’t care about the Wolfe crew; he spat on them. Built up an army of thugs around him. The Victory Boys.

And every night, every night, Diamond saw him go into the bedroom with Frenchie. Her own room was right next door to the big master bedroom and she wished it wasn’t because she could hear Frenchie’s pitiful cries through the wall. She knew Victor was hurting her. Frenchie, once so proud and upright, visibly drooped under the strain of it all. Owen started to flinch away from Victor before he was halfway into the room, hiding out in the back yard even when it rained. Diamond often found her youngest brother outside in the khazi, shivering with fear.

As for Diamond herself, mostly she tried to keep out of Victor’s way. She almost managed it, right up until her fourteenth birthday, when Moira – who had been cleaning Frenchie’s house ever since she came over from Paris – baked a special cake and Diamond had to blow out fourteen candles. It was a happy occasion, one of very few since Dad died and Victor had come storming into all their lives, but for Diamond it was blighted because she was aware of Victor’s speculative gaze on her throughout it all. Afterwards, while she was helping Moira with the washing-up in the scullery, with Moira’s young son Michael out chopping kindling in the yard, she could hear Victor talking to Frenchie in the kitchen.

‘Fourteen then,’ he was saying.

‘Yes. What of it?’ Frenchie sounded guarded.

Diamond exchanged a look with Moira. Moira was her great friend, she’d been with the family for years. She’d lost her husband a while back, and her son Michael, who was the same age as Diamond, was almost part of the family, just like she was.

‘She’s been good at the hoisting,’ said Victor.

That was true. Even at such a young age, Diamond, as a Butcher family member, was now pretty much in charge of the rest of the girls.

‘So?’ asked Frenchie.

‘She’s old enough, I reckon.’

‘For what?’

‘You know for what. I don’t carry no passengers. I thought I’d made that clear.’

‘No, she’s . . .’

‘She’s started her bleeds, I bet. Getting some tits on her. Nice-looking girl.’

Frenchie said nothing. In the scullery, Diamond and Moira listened, wide-eyed.

‘She can help me out then,’ Victor steamrollered on.

‘She already does. She does the hoisting. Isn’t that enough?’

‘Nah, I reckon she could do the trick.’

‘Victor, I don’t think . . .’

‘Who asked you to think? I do the thinking around here. And what I say goes – clear?’

No word from Frenchie.

‘I said . . .’ Victor’s tone had dropped to a silky threat.

‘Yes! All right,’ said Frenchie.

Diamond froze. What the hell had she just been signed up for?

8

That night at the Milano in Wardour Street, Diamond started doing the badger trick. She stood nervously at the bar and chatted to a young gentleman. Victor had told her the drill, and you didn’t disobey Victor. So she was smiling, flirting, encouraging the mark to buy her drinks and never quite finishing them, while Uncle Victor sat at a corner table watching the proceedings. She said – as Victor had told her to – that she would do a private dance for the young man in a room upstairs, if he liked.

Which, of course, he did.

Within the hour she was leading him up the stairs, bracing herself against self-disgust, fear and humiliation, dancing, removing her clothing bit by bit – and then Uncle Victor charged in and said, what the hell was going on? This was his daughter and this cad was dishonouring her. He should pay!

Diamond blanked her mind while Victor yelled and pounded the young man with his fists, then emptied his wallet, hustled him back down the stairs and threw him out of the club. She got dressed again. Then Victor came back up, smiling, saying what a good night’s work, peeling off fivers, tossing her one.

‘Good work, girl. Let’s get home,’ he said.

‘I don’t want to do this again,’ said Diamond.

Victor stopped in his tracks. ‘You what?’

Diamond repeated herself, her heart hammering with terror.

‘Right,’ said Victor, and moved like lightning, knocking her back on her arse. The blow caught her right in the eye. Then he yanked her up from the floor and struck again.

‘We won’t discuss this, ever again,’ he told her, breathing alcohol fumes into her aching, battered face. ‘You understand?’

Dazed, agonised, Diamond nodded.

‘Good,’ he said, and let her go.

***

Home didn’t feel like home any more. The minute they were through the door, Victor, who’d been downing whiskies all night and was now the worse for drink, started. Victor was horrible sober, but he was a bloody sight worse when the drink was on him. He caught poor Owen just going up to bed and kicked his arse hard to hasten his flight up the stairs. Aiden, who was in the hall, burst out in protest: ‘Hey!’

‘What did you say?’ snarled Victor, fists raised.

Aiden lowered his gaze and stared

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...